← Back to Budgeting and Saving

Needs vs wants is the foundation of every successful budget. A need is something you must pay for to survive and function, while a want is optional and improves your lifestyle. Understanding the difference helps you avoid overspending, save faster, and follow proven budgeting rules, such as the 50/30/20 method. In this guide, you’ll learn clear definitions, real-world examples, and a simple test to classify any expense correctly.

The math behind money starts with this fundamental distinction. When you control your wants, your money starts working for you instead of being consumed by lifestyle inflation.

Key Takeaways

- Needs are non-negotiable expenses required for survival, safety, and income generation, housing, utilities, basic food, insurance, and essential transportation

- Wants are discretionary spending that enhances lifestyle but aren’t required, dining out, entertainment subscriptions, upgraded electronics, and luxury purchases

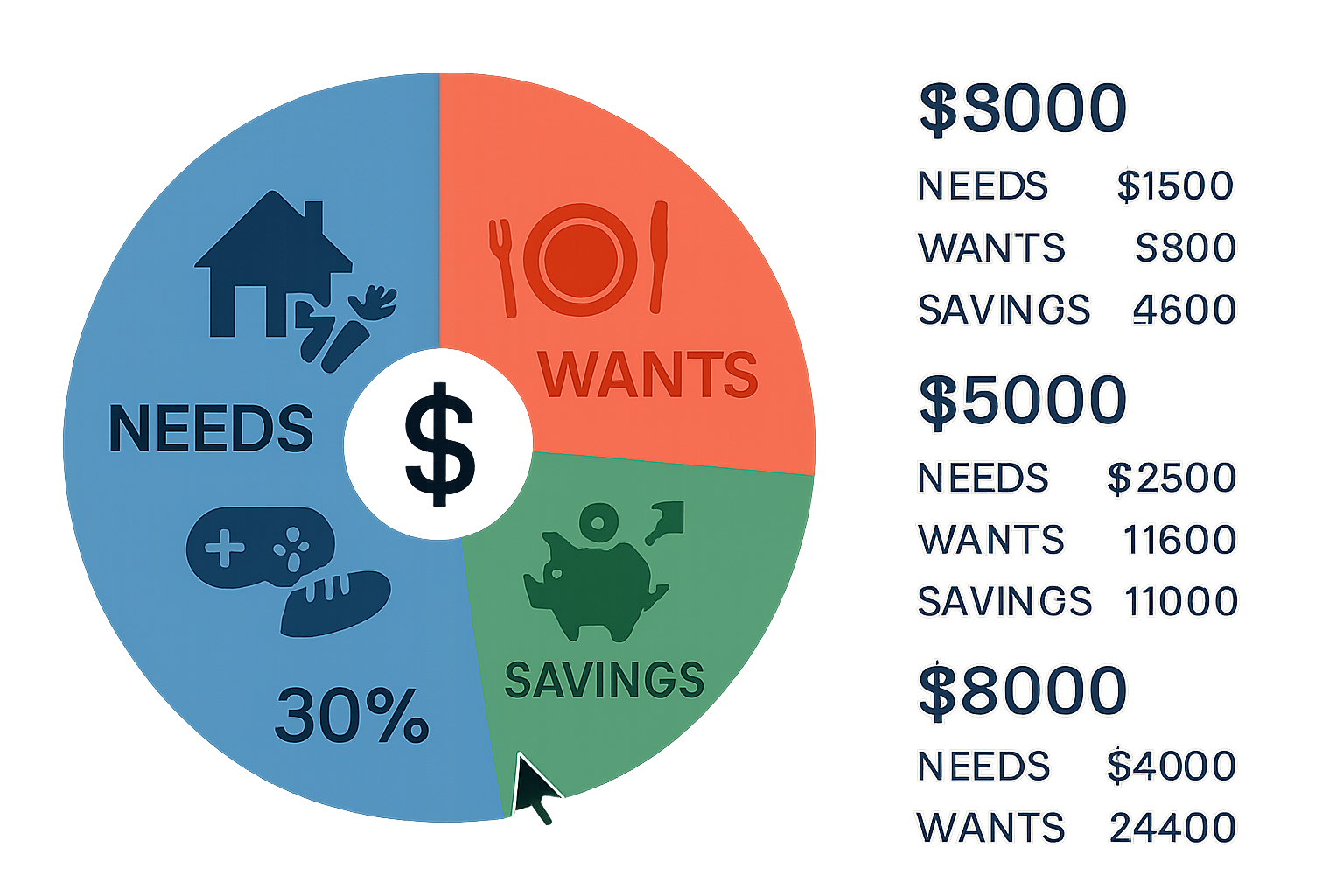

- The 50/30/20 rule allocates income strategically: 50% to needs, 30% to wants, and 20% to savings, creating a balanced approach to wealth building

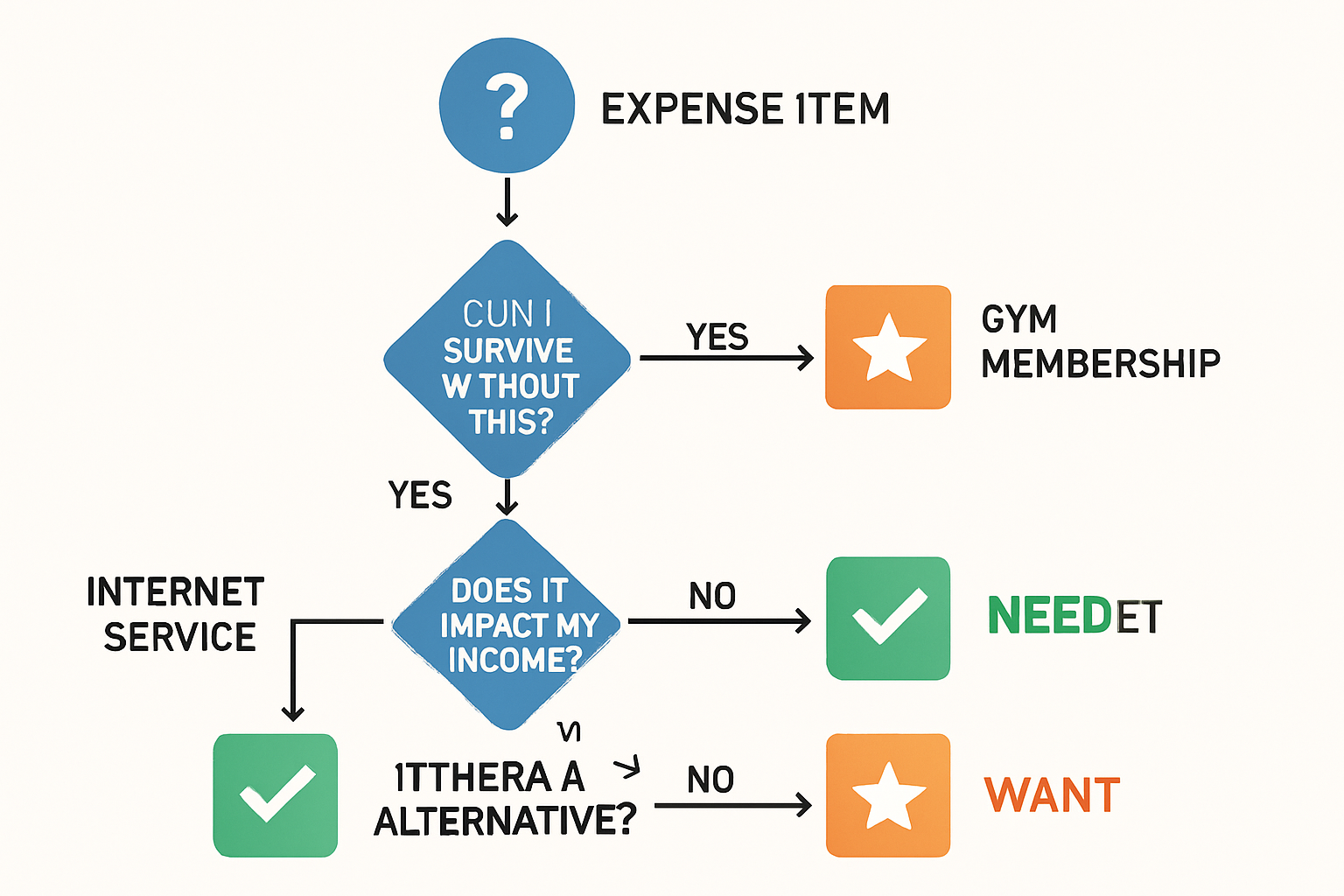

- Use the 3-question test to classify any expense: Can I survive without this? Does it impact my ability to earn? Is there a cheaper alternative?

- Misclassifying wants as needs is the primary cause of budget failure, credit card debt, and delayed financial independence

What Are Needs vs Wants? (The Core Distinction)

Needs vs Wants Explained

A need is an expense required for basic survival, safety, legal compliance, or the ability to generate income. Without it, your health deteriorates, your housing becomes unstable, or your capacity to work disappears.

A need includes:

- Housing: Rent or mortgage payments that keep you sheltered

- Utilities: Electricity, water, heat, and basic internet for work

- Food: Groceries for nutritious meals (not restaurants)

- Healthcare: Insurance premiums, necessary medications, essential medical care

- Transportation: Reliable vehicle or public transit to reach your job

- Minimum debt payments: Obligations that prevent default and credit damage

A want is an expense that improves comfort, entertainment, status, or convenience but isn’t required for survival or income generation. Eliminating a want creates inconvenience, not crisis.

A want includes:

- Dining out: Restaurants, coffee shops, food delivery services

- Entertainment: Streaming subscriptions, concerts, movies, gaming

- Upgraded products: Designer clothes, premium phones, luxury vehicles

- Travel: Vacations, weekend trips, non-essential flights

- Lifestyle upgrades: Gym memberships, premium subscriptions, hobby expenses

The distinction seems obvious until income increases. As earnings grow, wants disguise themselves as needs through a psychological process called lifestyle inflation, the tendency to upgrade spending as income rises, preventing wealth accumulation despite higher earnings.

Insight: The difference between needs and wants isn’t about deprivation. It’s about conscious allocation. Every dollar spent on wants is a dollar not working toward financial independence through compound growth.

Needs vs Wants Examples (Real-World Categories)

Needs Examples

These expenses keep you alive, housed, legally compliant, and capable of earning income:

Housing & Utilities

- Rent or mortgage payment (basic shelter)

- Property insurance (required by lenders)

- Basic electricity and water

- Heat in cold climates

- Internet service (if required for remote work)

Food & Health

- Grocery staples: rice, vegetables, protein, dairy

- Health insurance premiums

- Prescription medications

- Necessary medical procedures

- Basic hygiene products

Transportation & Income

- Reliable vehicle payment (if public transit unavailable)

- Car insurance (legally required)

- Gas for commuting to work

- Public transportation pass

- Vehicle maintenance prevents breakdowns

Financial Obligations

- Minimum debt payments (avoiding default)

- Child support or alimony

- Required professional licenses

- Work-mandated certifications

Wants Examples

These expenses enhance lifestyle but aren’t required for survival or income:

Food & Dining

- Restaurant meals and takeout

- Premium coffee shops

- Organic groceries (when conventional options exist)

- Gourmet ingredients and specialty foods

- Meal delivery services

Entertainment & Subscriptions

- Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, HBO Max

- Spotify Premium, Apple Music

- Gaming subscriptions (Xbox Game Pass, PlayStation Plus)

- Magazine and news subscriptions

- Audible and audiobook services

Lifestyle & Convenience

- Gym memberships (when home workouts are possible)

- Premium phone plans with unlimited data

- Latest smartphone models

- Designer clothing and accessories

- Home décor and furniture upgrades

Travel & Experiences

- Vacations and weekend getaways

- Concert and event tickets

- Hobby equipment and supplies

- Pet accessories beyond basic care

- Luxury vehicle upgrades

The challenge: many wants feel like needs because of social pressure, habit formation, or convenience. A $15 streaming subscription seems insignificant until you realize it represents $180 annually, money that could compound to $2,487 over 10 years at 7% annual growth.

Insight: The average American household spends 32% of its income on wants, yet reports feeling financially stressed. The math reveals the problem: wants consume potential savings that could generate passive income through investing.

Is It a Need or a Want? (The 3-Question Decision Framework)

When an expense exists in the gray area between necessity and luxury, apply this three-question test:

Question 1: Can I Survive Without This?

Test: If this expense disappeared tomorrow, would my health, safety, or housing be at immediate risk?

Examples:

- Electricity → Need (health risk in extreme temperatures)

- Cable TV → Want (inconvenient but not dangerous)

- Prescription medication → Need (health deteriorates without it)

- Vitamin supplements → Want (beneficial but not immediately critical)

Question 2: Does It Directly Impact My Ability to Earn Income?

Test: If I eliminate this expense, will my current job or income generation become impossible?

Examples:

- Internet service (remote worker) → Need (required for employment)

- Internet service (in-person worker) → Want (convenient but not required for income)

- Professional clothing (office job) → Need (workplace requirements)

- Designer professional clothing → Want (standard options exist)

- Vehicle (no public transit) → Need (only way to reach workplace)

- Luxury vehicle → Want (reliable transportation exists for less)

Question 3: Is There a Cheaper Alternative That Meets the Basic Requirement?

Test: Can I fulfill this need for significantly less money without sacrificing the core function?

Examples:

- $800 smartphone → Want (when $200 phones provide core functionality)

- $200 smartphone → Need (if required for work communication)

- Organic groceries → Want (when conventional groceries provide nutrition)

- Basic groceries → Need (essential nutrition)

- $50,000 vehicle → Want (when $15,000 vehicles provide reliable transport)

Decision Rule: If a cheaper alternative exists that fulfills the core requirement, the premium version is a want. The baseline version is the need.

This framework prevents the most common budgeting mistake: justification creep—the tendency to rationalize wants as needs through creative reasoning. “I need Netflix to relax after work” confuses preference with necessity.

Insight: The 3-question test eliminates emotional reasoning and applies objective criteria. When you classify expenses correctly, you discover that 60-70% of discretionary spending is wants, not needs[4].

Needs vs Wants in Budgeting (The 50/30/20 Rule)

How the 50/30/20 Rule Works

The 50/30/20 budgeting rule allocates after-tax income into three categories based on the needs vs wants framework:

50% → Needs (Essential expenses required for survival and income)

30% → Wants (Discretionary spending that enhances lifestyle)

20% → Savings (Emergency fund, retirement, debt payoff beyond minimums)

This allocation creates a balanced approach: you cover necessities, enjoy lifestyle improvements, and build wealth simultaneously. The rule prevents two common extremes, overspending on wants (leading to debt) or extreme frugality (leading to burnout).

The Math Behind the Allocation

For a household earning $5,000 per month after taxes:

| Category | Percentage | Monthly Amount | Annual Amount | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needs | 50% | $2,500 | $30,000 | Rent ($1,400), utilities ($150), groceries ($400), car payment ($300), insurance ($200), minimum debt payments ($50) |

| Wants | 30% | $1,500 | $18,000 | Dining out ($400), streaming services ($50), gym ($50), hobbies ($200), shopping ($300), entertainment ($500) |

| Savings | 20% | $1,000 | $12,000 | Emergency fund ($500), retirement contributions ($400), extra debt payments ($100) |

After 10 years, the 20% savings allocation ($1,000/month) compounds to $173,084 at a 7% annual return. This demonstrates why the rule works: consistent savings create exponential wealth through compound growth.

Adjusting the Rule by Income Level

The 50/30/20 rule serves as a baseline, but optimal allocation shifts with income:

Low Income ($2,500/month after taxes)

- Needs: 60-70% ($1,500-$1,750) — higher percentage due to fixed costs

- Wants: 10-15% ($250-$375) — minimal discretionary spending

- Savings: 15-25% ($375-$625) — aggressive savings despite lower income

Middle Income ($5,000/month after taxes)

- Needs: 50% ($2,500) — standard allocation

- Wants: 30% ($1,500) — balanced lifestyle spending

- Savings: 20% ($1,000) — consistent wealth building

High Income ($10,000/month after taxes)

- Needs: 30-40% ($3,000-$4,000) — lower percentage as fixed costs don’t scale

- Wants: 20-30% ($2,000-$3,000) — controlled lifestyle inflation

- Savings: 30-50% ($3,000-$5,000) — accelerated wealth accumulation

The key insight: as income rises, needs should consume a smaller percentage of total income because many needs (housing, utilities, food) don’t double when income doubles. This creates surplus capacity for aggressive saving.

Insight: The 50/30/20 rule fails when they want to disguise themselves as needs. A household claiming 70% of income goes to “needs” has misclassified expenses—likely counting restaurant meals, premium subscriptions, and upgraded products as necessities.

💰 Needs vs Wants Budget Calculator

Calculate your ideal 50/30/20 budget allocation

Your Budget Breakdown

📊 Annual Projections

Common Needs vs Wants Mistakes (Why Budgets Fail)

Mistake 1: Calling Luxuries "Needs"

The most destructive budgeting error is need inflation—the gradual reclassification of wants as needs through rationalization.

Common examples:

- "I need this $1,200 iPhone because I use it for work" (when a $300 phone provides the same work functionality)

- "I need to eat out because I don't have time to cook" (when meal prep takes 2 hours weekly)

- "I need this gym membership to stay healthy" (when home workouts and outdoor running are free)

- "I need premium cable because I deserve to relax" (when free entertainment options exist)

The psychological mechanism: hedonic adaptation—the tendency for increased consumption to become the new baseline, making luxuries feel essential[6].

The financial impact: A household that misclassifies $500/month in wants as needs ($6,000 annually) loses $82,870 in potential wealth over 10 years at 7% compound growth.

Solution: Apply the 3-question test ruthlessly. If a cheaper alternative exists that fulfills the core function, the premium version is a want.

Mistake 2: Lifestyle Inflation (The Silent Wealth Killer)

Lifestyle inflation occurs when spending rises proportionally with income, preventing wealth accumulation despite higher earnings.

The pattern:

- Income increases by $1,000/month

- Rent upgrades from $1,200 to $1,600 (+$400)

- Vehicle upgrades from $300 to $500 payment (+$200)

- Dining out increases from $200 to $400 (+$200)

- New subscriptions and services (+$200)

- Result: $1,000 income increase creates $1,000 spending increase, zero savings increase

The data confirms this pattern: households earning $100,000 annually report the same level of financial stress as those earning $50,000, because spending scales with income.

Solution: When income increases, maintain the same needs spending level and allocate the surplus to wants (30%) and savings (70%). This creates asymmetric wealth growth.

For a detailed framework on managing income increases, see the guide on active vs passive income.

Mistake 3: Not Adjusting During Income Changes

Budgets must flex with income volatility. The 50/30/20 rule works for stable income, but requires adjustment during:

Income Decrease (job loss, reduced hours, economic downturn)

- Needs: Increase to 60-70% (fixed costs don't decrease immediately)

- Wants: Decrease to 5-10% (eliminate discretionary spending)

- Savings: Decrease to 20-25% (maintain emergency fund contributions)

Income Increase (promotion, side income, bonus)

- Needs: Decrease to 30-40% (fixed costs don't scale with income)

- Wants: Maintain at 30% (controlled lifestyle improvement)

- Savings: Increase to 30-40% (accelerate wealth building)

Irregular Income (commission, freelance, seasonal work)

- Base budget on the minimum expected monthly income

- Treat above-average months as "bonus" for savings

- Build a larger emergency fund (6-12 months vs. 3-6 months)

The error: maintaining the same budget allocation regardless of income changes leads to overspending during downturns and missed wealth-building during upturns.

Mistake 4: Ignoring the Opportunity Cost

Every dollar spent on wants carries an opportunity cost; the compound growth that dollar could have generated if invested instead.

The math:

- $100 spent on wants today = $100 consumed

- $100 invested at 7% annual return = $196.72 in 10 years

- $100 invested at 7% annual return = $761.23 in 30 years

A daily $5 coffee habit ($1,825 annually) represents $25,188 in lost wealth over 10 years, or $173,367 over 30 years[8].

This doesn't mean eliminating all wants; it means understanding the trade-off. When you choose a want, you're choosing immediate gratification over future wealth. Make that choice consciously, not habitually.

Insight: The difference between financial independence and perpetual paycheck dependence often comes down to wanting control. Households that limit wants to 20-25% of income (instead of 30-40%) reach financial independence 8-12 years earlier.

Needs vs Wants by Income Level

Low Income ($2,000-$3,500/month after taxes)

At lower income levels, needs consume a higher percentage because fixed costs (housing, utilities, transportation) don't scale down proportionally.

Typical allocation:

- Needs: 60-70% — Housing, utilities, groceries, transportation, insurance

- Wants: 10-15% — Minimal discretionary spending

- Savings: 15-25% — Aggressive savings despite lower income

Example budget ($2,500/month):

- Needs: $1,625 (65%)

- Rent: $800

- Utilities: $150

- Groceries: $300

- Car payment: $200

- Insurance: $125

- Phone: $50

- Wants: $250 (10%)

- Entertainment: $100

- Dining out: $100

- Miscellaneous: $50

- Savings: $625 (25%)

- Emergency fund: $400

- Retirement: $225

Strategy: Focus on increasing income through skill development, side income, or career advancement. At low income levels, earning more creates more impact than cutting expenses further.

Consider exploring active income strategies to accelerate income growth.

Middle Income ($4,000-$7,000/month after taxes)

Middle income allows the standard 50/30/20 allocation with room for both lifestyle enjoyment and wealth building.

Typical allocation:

- Needs: 50% — Standard fixed costs

- Wants: 30% — Balanced discretionary spending

- Savings: 20% — Consistent wealth accumulation

Example budget ($5,000/month):

- Needs: $2,500 (50%)

- Rent/mortgage: $1,400

- Utilities: $150

- Groceries: $400

- Car payment: $300

- Insurance: $200

- Phone: $50

- Wants: $1,500 (30%)

- Dining out: $400

- Entertainment: $300

- Subscriptions: $100

- Hobbies: $200

- Shopping: $300

- Travel fund: $200

- Savings: $1,000 (20%)

- Emergency fund: $400

- 401(k): $400

- IRA: $200

Strategy: Maintain discipline on the 50/30/20 split. Resist lifestyle inflation as income grows within this range. Focus on optimizing savings through tax-advantaged accounts and low-cost index funds.

For retirement planning strategies, review the 4% rule for withdrawal planning.

High Income ($8,000+/month after taxes)

High income creates the opportunity for aggressive wealth building because needs represent a smaller percentage of total income.

Typical allocation:

- Needs: 30-40% — Fixed costs don't double with income

- Wants: 20-30% — Controlled lifestyle spending

- Savings: 30-50% — Accelerated financial independence

Example budget ($10,000/month):

- Needs: $3,500 (35%)

- Mortgage: $2,000

- Utilities: $200

- Groceries: $600

- Car payment: $400

- Insurance: $250

- Phone: $50

- Wants: $2,500 (25%)

- Dining out: $600

- Entertainment: $400

- Subscriptions: $150

- Hobbies: $400

- Shopping: $500

- Travel: $450

- Savings: $4,000 (40%)

- Emergency fund: $500

- 401(k) max: $1,917

- IRA max: $583

- Taxable brokerage: $1,000

Strategy: Avoid the high-income trap, lifestyle inflation that consumes earnings growth. Many high earners spend 60-70% on wants, delaying financial independence despite substantial income.

The math: Saving 40% of a $10,000 monthly income ($4,000/month) creates $691,333 in 10 years at 7% growth, enough to generate $27,653 in annual passive income using the 4% withdrawal rule.

Insight: Income level changes the percentages, but the principle remains constant: needs should consume the minimum required for safety and income generation, leaving maximum capacity for wealth building.

How to Track Needs vs Wants (Implementation Tools)

Method 1: Budget Apps (Automated Tracking)

Best for: Beginners who want automatic categorization and visual dashboards.

Top options:

- Mint (free) — Automatic transaction categorization, spending trends, budget alerts

- YNAB (You Need A Budget) ($14.99/month) — Zero-based budgeting, goal tracking, educational resources

- EveryDollar (free basic, $17.99/month premium) — Simple interface, debt payoff tracking

- Personal Capital (free) — Investment tracking, net worth monitoring, retirement planning

How it works:

- Connect bank accounts and credit cards

- Review auto-categorized transactions

- Manually adjust needs vs wants classifications

- Monitor spending against 50/30/20 targets

- Receive alerts when categories exceed limits

Advantage: Automation reduces manual effort and provides real-time spending visibility.

Disadvantage: Auto-categorization often misclassifies expenses, requiring manual review.

Method 2: Spreadsheet Method (Manual Control)

Best for: Intermediate users who want complete customization and data control.

Setup:

- Create three sheets: Budget Plan, Transaction Log, Monthly Summary

- List all income sources and amounts

- Categorize every expense as Need, Want, or Savings

- Calculate the percentage allocation for each category

- Compare actual spending to 50/30/20 targets

Template structure:

| Date | Description | Amount | Category | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3/1/25 | Rent | $1,400 | Housing | Need |

| 3/2/25 | Groceries | $85 | Food | Need |

| 3/3/25 | Netflix | $15 | Entertainment | Want |

| 3/4/25 | 401(k) | $400 | Retirement | Savings |

Advantage: Complete control, customization, and no subscription fees.

Disadvantage: Requires manual data entry and discipline to maintain.

For a comprehensive budgeting framework, explore the complete 50/30/20 rule guide.

Method 3: Envelope System (Physical Cash Control)

Best for: Visual learners and those who overspend with cards.

How it works:

- Withdraw the monthly budget in cash

- Divide cash into physical envelopes labeled by category

- Spend only from designated envelopes

- When an envelope empties, stop spending in that category

Categories:

- Needs: Groceries, gas, utilities (cash-payable items)

- Wants: Dining out, entertainment, shopping

- Savings: Physical deposit to savings account

Advantage: Physical limitation prevents overspending. Cash spending creates psychological awareness.

Disadvantage: Inconvenient for online purchases, bill payments, and tracking.

Method 4: Two-Account System (Automated Separation)

Best for: Those who want automatic needs/wants separation without manual tracking.

Setup:

- Account 1 (Needs): Receives 50% of income, pays all essential expenses via autopay

- Account 2 (Wants + Savings): Receives 50% of income, allocates 30% to discretionary spending, 20% to savings

Implementation:

- Set up direct deposit split: 50% to checking (needs), 50% to secondary account

- Automate all needs payments from the primary checking account

- Manually manage wants and savings from the secondary account

- Never touch needs account for discretionary spending

Advantage: Automatic separation prevents needs/wants confusion. Ensures bills get paid first.

Disadvantage: Requires discipline not to transfer from needs account for wants.

Insight: The best tracking method is the one you'll actually use consistently. Start simple, then increase complexity as budgeting becomes habitual.

Conclusion: Master the Distinction, Control Your Future

Needs vs wants isn't about deprivation—it's about conscious allocation.

Every dollar you earn faces a choice: immediate consumption or future freedom. Needs represent the baseline cost of survival and income generation. Wants represent lifestyle enhancement. Savings represent compound growth toward financial independence.

The math is unforgiving: households that misclassify wants as needs spend 60-70% of income on consumption, leaving minimal capacity for wealth building. Those who correctly classify expenses and follow the 50/30/20 framework allocate 20-40% to savings, reaching financial independence 10-15 years earlier.

Your action steps:

- Track 30 days of spending — Categorize every expense as need, want, or savings

- Apply the 3-question test — Reclassify misidentified wants currently disguised as needs

- Calculate your current allocation — Determine actual percentages for needs/wants/savings

- Implement the 50/30/20 rule — Adjust spending to target allocations

- Automate the system — Set up separate accounts or use apps to enforce boundaries

- Review quarterly — Reassess classifications as income and circumstances change

The difference between financial stress and financial freedom isn't income—it's the distinction between needs and wants. Master this classification, and your money starts working for you instead of being consumed by lifestyle inflation.

When you control your wants, you control your future.

For additional budgeting strategies, explore the 20/4/10 rule for car buying and the 3x rent rule for housing decisions.

About the Author

Max Fonji is a data-driven financial educator and the voice behind The Rich Guy Math. With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based investing, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable frameworks. His work focuses on the math behind money, demonstrating through data, formulas, and compound growth principles how wealth building actually works. Max's educational approach combines analytical precision with approachable teaching, helping readers understand the cause-and-effect relationships that drive financial success.

Educational Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. The content represents general principles and frameworks for understanding needs vs wants classification and budgeting strategies. Individual financial situations vary significantly based on income, expenses, goals, geographic location, and personal circumstances.

The 50/30/20 rule and other budgeting frameworks discussed are guidelines, not universal prescriptions. Optimal allocation percentages depend on individual circumstances, income levels, and financial goals. Compound growth projections assume consistent contributions and average market returns, which are not guaranteed.

Before making financial decisions, consult with qualified financial advisors, tax professionals, or certified financial planners who can assess your specific situation. Past performance does not guarantee future results. All investment and savings strategies carry risk, including potential loss of principal.

The Rich Guy Math and its authors are not registered investment advisors, certified financial planners, or licensed tax professionals. This content does not create a client-advisor relationship.

References

[1] Federal Reserve Board. (2024). "Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households." Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/

[2] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). "Consumer Expenditure Survey." U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/cex/

[3] American Psychological Association. (2024). "Stress in America: Money and Financial Concerns." APA Research. https://www.apa.org/

[4] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2024). "Financial Well-Being in America." CFPB Research. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/

[5] Securities and Exchange Commission. (2024). "Compound Interest Calculator Methodology." Investor.gov. https://www.investor.gov/

[6] Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2023). "Hedonic Adaptation and Consumption Patterns." Journal of Behavioral Economics. https://www.aeaweb.org/

[7] Pew Research Center. (2024). "Income, Spending, and Financial Stress Across Economic Classes." Pew Economic Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/

[8] Morningstar Investment Research. (2024). "Opportunity Cost of Discretionary Spending." Morningstar Direct. https://www.morningstar.com/

[9] CFA Institute. (2024). "Savings Rate and Time to Financial Independence Analysis." CFA Research Foundation. https://www.cfainstitute.org/

[10] National Bureau of Economic Research. (2024). "High-Income Households and Lifestyle Inflation Patterns." NBER Working Papers. https://www.nber.org/

FAQ: Needs vs Wants

Is rent a need or a want?

Rent is a need because shelter is required for survival and safety. However, the amount of rent can include want components.

A $1,200 apartment that provides safe, functional housing is a need. Upgrading to a $2,000 apartment for luxury amenities, premium location, or extra space beyond necessity contains want elements.

Apply the 3-question test: the baseline housing required for safety is a need; premium upgrades are wants.

Is internet a need or a want?

Internet is context-dependent. For remote workers, freelancers, or students who require online access for income or education, basic internet service is a need.

For people who work in-person and use internet primarily for entertainment, it is a want.

The key distinction: if eliminating internet prevents you from earning income or completing required education, it’s a need. If it only removes entertainment or convenience, it’s a want.

Are subscriptions wants?

Most subscriptions are wants. Streaming services, gym memberships, meal kits, and premium apps improve lifestyle but aren’t required for survival or income generation.

Exceptions include subscriptions directly required for work, such as professional software, industry publications, or mandatory certifications.

Ask: would losing this subscription prevent you from earning income or maintaining health? If not, it’s a want.

Can a want become a need?

Yes. Classification changes based on circumstances, not preferences.

A car is a want in cities with reliable public transportation, but becomes a need in rural areas where commuting to work is impossible without one.

Similarly, internet may be a want for in-person workers but becomes a need when transitioning to remote work.

How do I stop justifying wants as needs?

Use objective criteria instead of emotional reasoning. Apply the 3-question test to every expense.

Ask yourself: “Would I still classify this as a need if I earned half my current income?”

Emotional justifications like “I deserve this” or “everyone has this” signal a want. Needs don’t require justification.

What percentage of income should go to needs?

A common guideline is the 50/30/20 rule, where 50% of income goes to needs.

Low-income households may require 60–70% due to fixed costs. High-income households should aim for 30–40% as income rises faster than essential expenses.

If needs exceed 60%, either income is too low or lifestyle costs—especially housing or transportation—are too high.

Is eating out ever a need?

Eating out is almost always a want. The need is nutrition, which groceries provide at 60–80% lower cost than restaurants.

Rare exceptions include business meals required to generate income or maintain client relationships.

Convenience, time savings, or taste preferences don’t convert restaurant spending into needs—they are valid wants that should come from discretionary spending.