Ever wondered why your accountant uses different terms to describe how assets lose value? You’re not alone. Amortization and depreciation might sound like accounting jargon, but understanding these concepts can transform how you view business finances, investment opportunities, and even your personal wealth-building strategy.

Whether you’re analyzing financial statements for stock market investments, running a small business, or simply trying to understand how companies report their earnings, knowing the difference between amortization vs depreciation is essential. These accounting methods affect everything from tax obligations to company valuations—and they’re simpler to grasp than you might think.

TL;DR

- Amortization spreads the cost of intangible assets (like patents, copyrights, or goodwill) over their useful life, while depreciation does the same for tangible physical assets (like buildings, machinery, or vehicles).

- Both amortization and depreciation are non-cash expenses that reduce taxable income, helping businesses save money on taxes without affecting actual cash flow.

- Understanding amortization vs depreciation is crucial for what is investing decisions, as these expenses directly impact a company’s reported earnings and book value.

- Different calculation methods exist for both (straight-line, declining balance, etc.), with straight-line being the most common and easiest to understand.

- Neither amortization nor depreciation represents actual cash leaving the company—they’re accounting allocations that match expenses with the revenue they help generate.

What Are Amortization and Depreciation?

Let’s start with the fundamentals. In simple terms, amortization and depreciation are accounting methods used to allocate the cost of an asset over its useful life. Instead of recording the entire purchase price as an expense in year one, these methods spread that cost across multiple years.

What Is Depreciation?

Depreciation refers to the systematic reduction in the recorded value of a tangible (physical) asset over time. Think of a delivery truck that gets worn down from daily use, or a computer that becomes obsolete after several years. The formula for straight-line depreciation is:

Depreciation Expense = (Asset Cost – Salvage Value) / Useful Life

What Is Amortization?

Amortization, on the other hand, applies to intangible assets—things you can’t physically touch but that still have value. This includes patents, trademarks, copyrights, and customer lists. The basic formula mirrors depreciation:

Amortization Expense = (Asset Cost – Residual Value) / Useful Life

Both concepts follow the matching principle in accounting, which states that expenses should be recorded in the same period as the revenues they help generate. This creates a more accurate picture of a company’s profitability over time.

Why Do Amortization and Depreciation Matter?

Understanding amortization vs depreciation isn’t just academic—it has real-world implications for investors, business owners, and anyone interested in smart ways to make passive income. Here’s why these concepts matter:

Tax Benefits

Both amortization and depreciation are tax-deductible expenses. This means businesses can reduce their taxable income without spending any actual cash. For example, if a company buys a $100,000 machine and depreciates it over 10 years, they can deduct $10,000 annually from their taxable income—even though they only spent the cash once, in year one.

Cash Flow vs Profitability

Since these are non-cash expenses, they create an interesting dynamic: a company can report lower net income (due to depreciation and amortization expenses) while maintaining strong cash flow. Savvy investors look at metrics like EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) to understand the true cash-generating power of a business.

Asset Valuation

Over time, depreciation and amortization reduce the book value of assets on a company’s balance sheet. This affects key financial ratios and can influence investment decisions, particularly when analyzing dividend-paying companies.

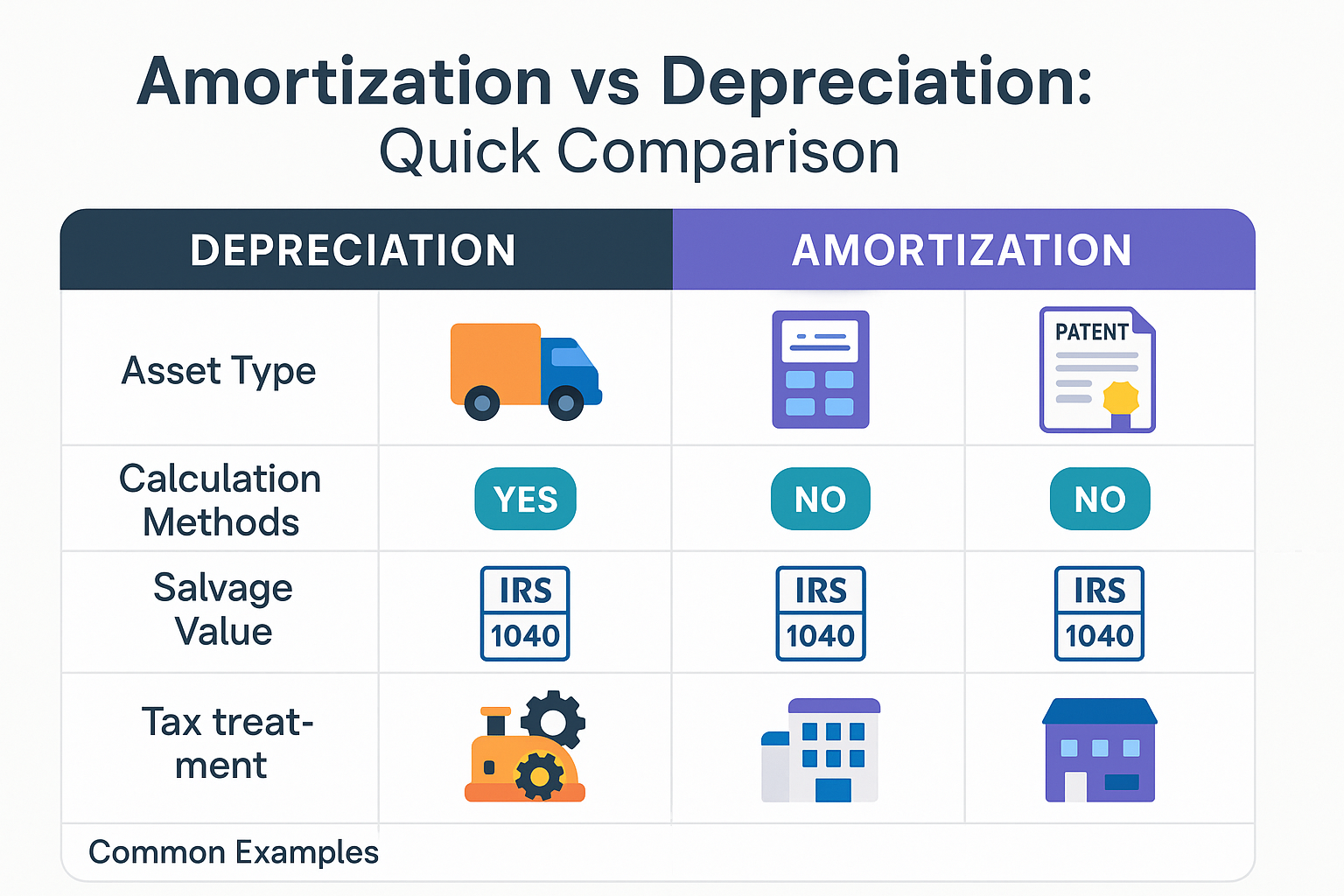

The Core Differences: Amortization vs Depreciation

While amortization and depreciation serve similar purposes, several key differences set between amortization vs depreciation apart. Let’s break down the comparison:

| Aspect | Depreciation | Amortization |

|---|---|---|

| Asset Type | Tangible (physical) assets | Intangible (non-physical) assets |

| Examples | Buildings, vehicles, machinery, equipment, furniture | Patents, copyrights, trademarks, goodwill, customer lists |

| Salvage Value | Often has residual/salvage value | Typically assumes zero residual value |

| Calculation Methods | Straight-line, declining balance, units of production, sum-of-years-digits | Primarily straight-line method |

| Balance Sheet Presentation | Accumulated depreciation shown separately | Often netted against the intangible asset |

| IRS Section | Section 179 and MACRS | Section 197 (15-year amortization for most intangibles) |

Tangible vs. Intangible Assets

The most fundamental difference in the amortization vs depreciation debate is the type of asset being expensed:

Depreciation applies to tangible assets—things you can see, touch, and physically inspect. These include:

- Buildings and real estate improvements

- Vehicles and transportation equipment

- Manufacturing machinery

- Office furniture and fixtures

- Computer hardware

- Tools and equipment

Amortization applies to intangible assets—valuable items that exist conceptually rather than physically:

- Patents and intellectual property

- Copyrights and trademarks

- Franchise agreements

- Customer relationships and lists

- Software and licensing rights

- Goodwill (in certain cases)

Calculation Methods and Flexibility

While both use similar mathematical approaches, depreciation offers more calculation flexibility than amortization.

Depreciation methods include:

- Straight-Line Method (most common): Equal expense each year

- Declining Balance Method: Higher expenses in early years

- Double-Declining Balance: Accelerated depreciation

- Units of Production: Based on actual usage

- Sum-of-Years-Digits: Another accelerated method

Amortization methods are simpler:

Most intangible assets use the straight-line method exclusively. The IRS requires most acquired intangible assets to be amortized over exactly 15 years under Section 197, regardless of their actual useful life.

Real-World Examples: Seeing the Concepts in Action

Let’s make this concrete with practical examples that show how amortization vs depreciation work in real business scenarios.

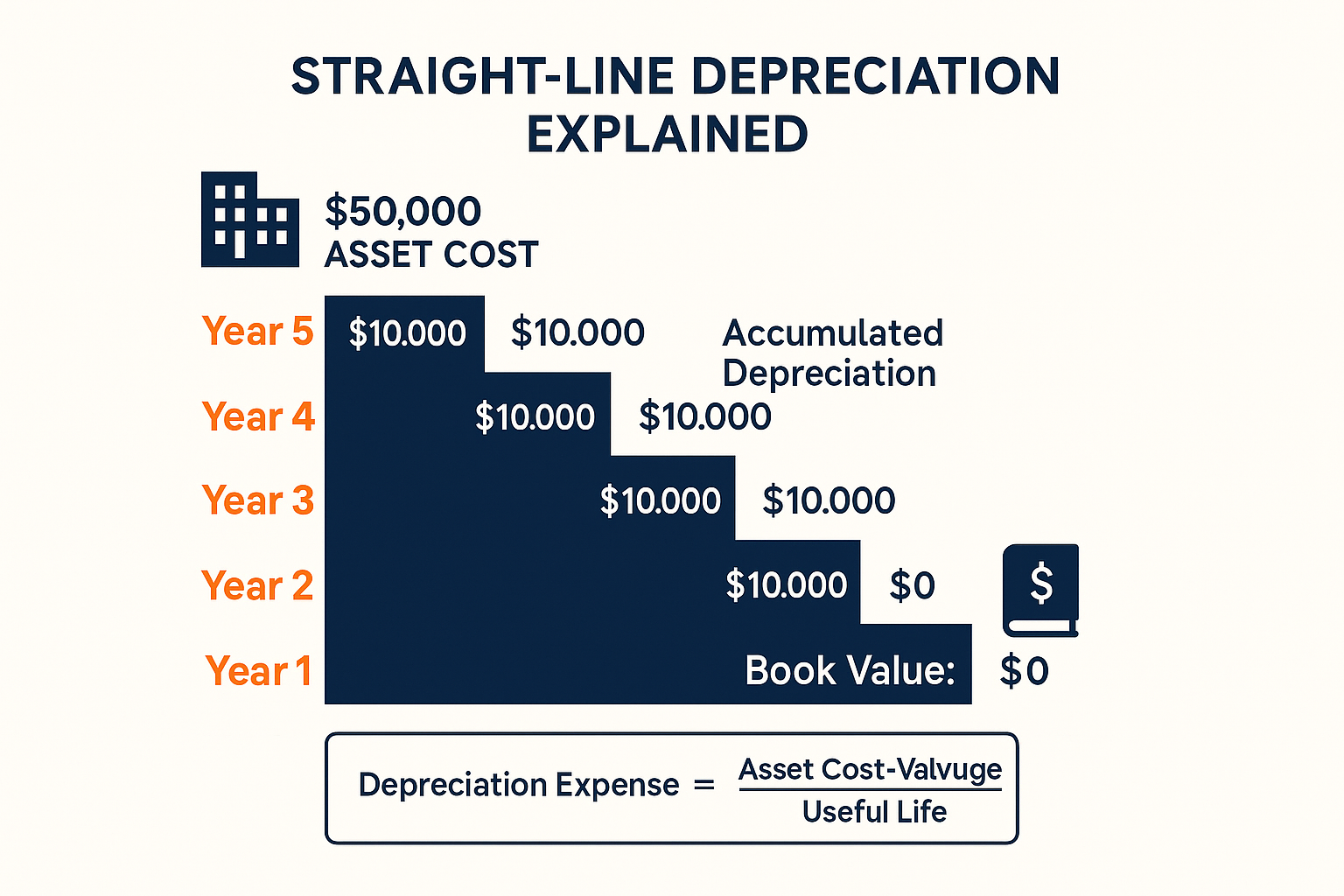

Depreciation Example: The Delivery Company

Imagine a delivery company purchases a new truck for $60,000. The company expects the truck to last 10 years and estimates it will have a salvage value of $10,000 at the end of its useful life.

Using straight-line depreciation:

- Annual Depreciation = ($60,000 – $10,000) / 10 years = $5,000 per year

Each year for the next decade, the company records a $5,000 depreciation expense on its income statement. This reduces reported profits by $5,000 annually, lowering the company’s tax bill. Meanwhile, the truck’s book value on the balance sheet decreases by $5,000 each year.

Year 1: Book value = $55,000

Year 5: Book value = $35,000

Year 10: Book value = $10,000 (salvage value)

Amortization Example: The Software Startup

Now consider a software company that purchases a patent for a revolutionary algorithm for $150,000. The patent has a legal life of 20 years, but the company expects it to provide competitive advantages for only 10 years before becoming obsolete.

Using straight-line amortization (with no residual value):

- Annual Amortization = $150,000 / 10 years = $15,000 per year

For the next 10 years, the company records $15,000 in amortization expense annually. This non-cash expense reduces taxable income while the patent continues generating revenue through the company’s proprietary software.

Combined Example: Understanding Company Financials

When analyzing companies for stock market investments, you’ll often see both depreciation and amortization on the income statement. A manufacturing company might show:

- Depreciation expense: $2 million (factory equipment, buildings, vehicles)

- Amortization expense: $500,000 (acquired patents, customer relationships)

- Total D&A: $2.5 million

This $2.5 million reduces reported net income but doesn’t represent cash that left the company. Understanding this distinction helps investors evaluate the true profitability and cash-generation capability of potential investments.

📊 Depreciation & Amortization Calculator

Calculate annual expenses and view detailed schedules

| Year | Depreciation | Accumulated | Book Value |

|---|

| Year | Amortization | Accumulated | Book Value |

|---|

How Depreciation Works: Methods and Calculations

Understanding the different depreciation methods helps you interpret financial statements more accurately and make better investing decisions. Let’s explore the most common approaches.

Straight-Line Depreciation Method

The straight-line method is the simplest and most widely used depreciation approach. It allocates an equal expense amount to each year of an asset’s useful life.

Formula: (Asset Cost – Salvage Value) / Useful Life = Annual Depreciation

Advantages:

- Simple to calculate and understand

- Predictable expense amounts

- Matches well with assets that wear evenly over time

- Widely accepted for financial reporting

Disadvantages:

- Doesn’t reflect accelerated wear in early years

- May not match the actual value decline

- Less tax benefit in the early years compared to the accelerated methods

Declining Balance Method

The declining balance method (also called accelerated depreciation) front-loads depreciation expenses, recording larger amounts in the early years of an asset’s life.

The most common version is the double-declining balance method, which uses twice the straight-line rate:

Rate = (2 / Useful Life) × 100%

For example, a 10-year asset would have a 20% annual depreciation rate (2/10 = 0.20).

This method better reflects how many assets lose value—rapidly at first, then more slowly over time. It also provides greater tax benefits in the early years, improving cash flow when businesses need it most.

Units of Production Method

Some assets depreciate based on usage rather than time. Manufacturing equipment, for instance, might depreciate based on units produced or hours operated.

Formula: (Asset Cost – Salvage Value) / Total Estimated Units × Units Produced This Period

This method provides the most accurate expense matching for assets whose wear depends on activity levels rather than age.

MACRS (Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System)

For U.S. tax purposes, the IRS requires most businesses to use MACRS, a system that assigns assets to specific recovery periods and applies predetermined depreciation percentages.

MACRS generally results in faster depreciation than straight-line, providing tax benefits sooner. However, companies often use different methods for financial reporting versus tax reporting—straight-line for the former, MACRS for the latter.

How Amortization Works: Simpler But Strategic

Compared to depreciation, amortization is more straightforward—but that doesn’t make it less important for understanding business financials.

Standard Amortization Approach

Most intangible assets are amortized using the straight-line method over their useful economic life. Unlike depreciation, amortization typically assumes zero residual value—intangible assets rarely have salvage value.

Formula: Asset Cost / Useful Life = Annual Amortization Expense

Section 197 Intangibles

Under U.S. tax law, Section 197 intangibles must be amortized over exactly 15 years, regardless of their actual useful life. This category includes:

- Goodwill

- Going concern value

- Workforce in place

- Business books and records

- Customer-based intangibles

- Supplier-based intangibles

- Licenses, permits, and rights granted by the government

- Covenants not to compete

- Franchises, trademarks, and trade names

This standardization simplifies tax compliance but can create timing differences between book and tax reporting.

Amortization of Loans

It’s worth noting that “amortization” has another meaning in finance: the gradual repayment of a loan through scheduled payments. Each payment includes both principal and interest, with the principal portion “amortizing” (reducing) the loan balance over time.

While conceptually similar to asset amortization—both involve spreading costs over time—loan amortization is a separate concept that won’t be our focus here.

Tax Implications: How Amortization vs Depreciation Affects Your Bottom Line

Both amortization and depreciation create significant tax advantages for businesses, but the specifics differ in important ways.

Depreciation Tax Benefits

Section 179 Deduction: Businesses can immediately expense up to $1,220,000 (2025 limit) of qualifying property in the year of purchase, rather than depreciating it over time. This provides a massive first-year tax benefit for small and medium-sized businesses.

Bonus Depreciation: In addition to Section 179, businesses may qualify for bonus depreciation, which allows immediate expensing of a percentage of qualifying asset costs.

MACRS Advantages: Even without Section 179 or bonus depreciation, MACRS generally provides faster depreciation than straight-line, accelerating tax benefits.

Amortization Tax Benefits

15-Year Recovery Period: Section 197 intangibles must be amortized over 15 years, providing consistent tax deductions throughout that period.

No Section 179 or Bonus Depreciation: Unlike tangible assets, most intangible assets don’t qualify for immediate expensing under Section 179 or bonus depreciation rules.

Software Exception: Certain software costs can be depreciated over 3 years using MACRS, or immediately expensed under Section 179—a notable exception to standard amortization rules.

Strategic Tax Planning

Understanding these differences helps businesses make strategic purchasing decisions. For example:

- Timing purchases: Acquiring depreciable assets before year-end can maximize Section 179 deductions

- Lease vs. buy decisions: Depreciation benefits may favor purchasing over leasing

- Asset allocation in acquisitions: How the purchase price is allocated between tangible assets, intangible assets, and goodwill affects the depreciation and amortization schedule

Impact on Financial Statements and Key Metrics

When analyzing companies for stock market investments, understanding how amortization vs depreciation affects financial statements is crucial.

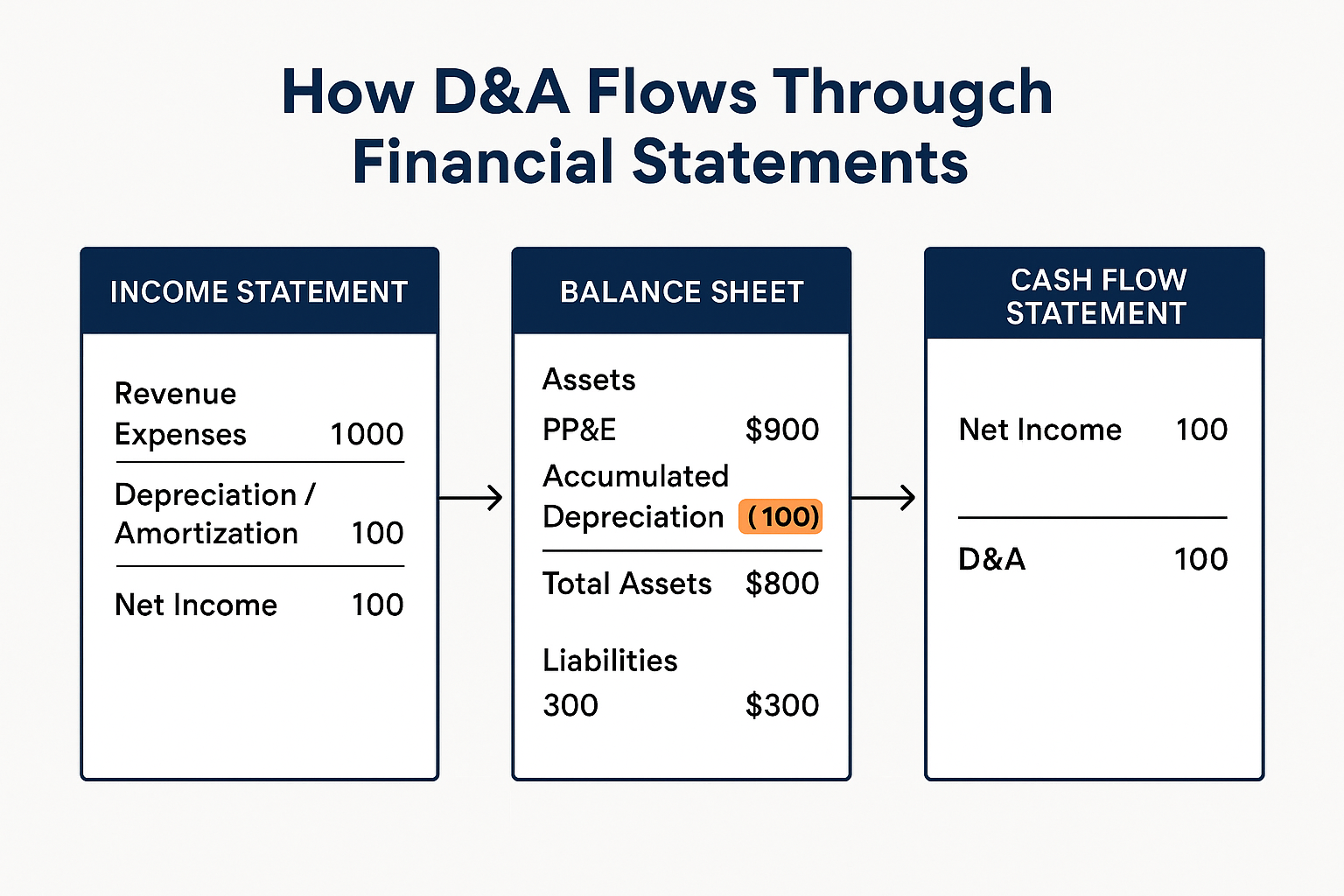

Income Statement Impact

Both depreciation and amortization appear as operating expenses on the income statement, reducing reported earnings. However, because they’re non-cash expenses, they don’t affect cash flow.

This creates an important distinction: Net Income ≠ Cash Flow

A company might report low net income due to high depreciation and amortization, yet generate strong cash flow. Conversely, a company with low D&A might report high net income while struggling with cash.

Balance Sheet Impact

Depreciation reduces the carrying value of tangible assets over time. The balance sheet typically shows:

- Gross Property, Plant & Equipment (PP&E): Original cost

- Less: Accumulated Depreciation: Total depreciation taken to date

- Net PP&E: Current book value

Amortization similarly reduces intangible asset values, though it’s often netted directly against the asset rather than shown separately.

Key Metrics Affected

Several important financial ratios incorporate or exclude depreciation and amortization:

EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization): This metric adds back D&A to show operating performance before non-cash expenses. It’s widely used to compare companies with different capital structures and tax situations.

Operating Cash Flow: Calculated by adding back depreciation and amortization to net income (along with other adjustments), since these are non-cash expenses.

Return on Assets (ROA): As depreciation reduces asset values on the balance sheet, it can artificially inflate return on assets (ROA) over time, making older assets appear more efficient.

Book Value: Depreciation and amortization reduce total assets and shareholders’ equity, lowering book value per share.

Common Mistakes and Misconceptions

Even experienced investors sometimes misunderstand aspects of amortization vs depreciation. Let’s clear up some common confusion.

Mistake #1: Thinking Depreciation Represents Cash

The Truth: Depreciation and amortization are accounting allocations, not cash expenses. The cash left the business when the asset was purchased. These expenses simply spread that historical cost over multiple periods.

This is why savvy investors focus on cash flow metrics alongside reported earnings. A company can be “unprofitable” on paper while generating substantial cash.

Mistake #2: Ignoring Differences Between Book and Tax Depreciation

The Truth: Companies often use different depreciation methods for financial reporting (usually straight-line) versus tax reporting (usually MACRS). This creates deferred tax liabilities or assets on the balance sheet.

Understanding these timing differences helps investors interpret tax expense and predict future tax obligations.

Mistake #3: Assuming Amortization Applies to All Intangibles

The Truth: Not all intangible assets are amortized. Indefinite-lived intangibles—like brand names and trademarks that can theoretically last forever—are not systematically amortized. Instead, they’re tested annually for impairment.

Goodwill, the premium paid in acquisitions over the fair value of identifiable assets, also isn’t amortized under current U.S. GAAP (though it was before 2001). Instead, it’s subject to annual impairment testing.

Mistake #4: Overlooking Fully Depreciated Assets Still in Use

The Truth: Just because an asset is fully depreciated doesn’t mean it’s worthless or no longer in use. Many companies continue operating equipment and buildings long after they’ve been fully depreciated.

This can make balance sheet asset values misleading—a company with old, fully-depreciated equipment might have significant productive capacity not reflected in book value.

Mistake #5: Confusing Amortization with Amortization of Loans

The Truth: As mentioned earlier, “amortization” has two distinct meanings:

- Asset amortization: Expensing intangible assets over time

- Loan amortization: Paying down debt principal over time

While conceptually related (both involve spreading costs over periods), they’re completely different in practice and appear in different parts of financial statements.

Amortization vs Depreciation in Investment Analysis

For investors evaluating companies—whether for dividend income or capital appreciation—understanding amortization vs depreciation provides crucial insights.

Analyzing Capital-Intensive Businesses

Companies in manufacturing, transportation, utilities, and telecommunications typically have high depreciation expenses relative to revenue. When analyzing these businesses:

Look at capital expenditure (CapEx) trends: Is the company spending enough to maintain its asset base? If CapEx consistently falls below depreciation, the company might be underinvesting in asset replacement.

Compare depreciation methods: Conservative companies use shorter useful lives and lower salvage values, resulting in higher depreciation. This reduces reported earnings but creates a “cushion” of conservatism.

Evaluate asset age: Calculate the average age of PP&E by dividing accumulated depreciation by depreciation expense. Older asset bases may indicate upcoming replacement needs.

Understanding Tech and Service Companies

Technology and service businesses often have higher amortization relative to depreciation because their value lies in intangible assets—software, patents, customer relationships, and brand value.

When analyzing these companies:

Examine R&D spending: Companies that expense R&D as incurred (most U.S. companies) show lower earnings than those capitalizing and amortizing development costs. This affects comparability.

Assess acquisition activity: Serial acquirers accumulate substantial intangible assets and goodwill, leading to high amortization. This can depress reported earnings while cash flow remains strong.

Watch for impairments: Unlike systematic amortization, impairments are sudden write-downs when intangible asset values decline. These can signal strategic missteps or market changes.

Using EBITDA Wisely

EBITDA has become a popular metric precisely because it eliminates the effects of depreciation and amortization, allowing investors to focus on operating performance. However, it has limitations:

EBITDA ignores capital intensity: Two companies with identical EBITDA might have vastly different capital requirements. The one with higher depreciation probably requires more ongoing investment.

EBITDA isn’t cash flow: It doesn’t account for working capital changes, CapEx, or tax payments—all of which affect actual cash generation.

Industry context matters: EBITDA is more meaningful in industries with predictable capital needs and less useful where capital requirements vary significantly.

For a more complete picture, consider Free Cash Flow (Operating Cash Flow minus CapEx), which accounts for the actual cash required to maintain and grow the business.

Real-World Industry Examples

Different industries rely on different mixes of tangible and intangible assets, making amortization vs depreciation more or less prominent.

Manufacturing: Depreciation-Heavy

A typical automotive manufacturer might show:

- High depreciation: Factories, assembly lines, robotics, and tooling

- Moderate amortization: Patents and design rights

- Capital intensity: Requires ongoing investment to replace worn equipment

Investor takeaway: Watch the ratio of CapEx to depreciation. Healthy manufacturers typically spend at least as much on CapEx as their depreciation expense to maintain productive capacity.

Software/SaaS: Amortization-Heavy

A software-as-a-service company might show:

- Low depreciation: Minimal physical assets beyond servers and office equipment

- High amortization: Capitalized software development costs, acquired customer relationships

- Intangible value: Most value in intellectual property and customer base

Investor takeaway: Focus on metrics like customer acquisition cost, lifetime value, and recurring revenue rather than traditional asset-based ratios.

Telecommunications: Both High

Telecom companies typically have:

- High depreciation: Cell towers, fiber optic networks, switching equipment

- High amortization: Spectrum licenses, customer relationships from acquisitions

- Massive capital requirements: Ongoing network upgrades and expansion

Investor takeaway: Evaluate whether cash flow can support both CapEx needs and debt service, as telecoms often carry substantial leverage.

Retail: Depreciation-Focused

Retailers generally show:

- Moderate depreciation: Store fixtures, point-of-sale systems, distribution centers

- Low amortization: Limited intangible assets unless acquired

- Lease considerations: Many retailers lease rather than own, reducing depreciation but increasing operating expenses

Investor takeaway: Compare operating lease obligations to owned asset depreciation for a complete picture of occupancy costs.

How to Use This Knowledge in Your Investment Strategy

Understanding amortization vs depreciation isn’t just academic—it provides practical advantages for building wealth through investing.

Screening for Quality Companies

High-quality businesses often show:

- Consistent CapEx at or above depreciation (maintaining competitive position)

- Conservative depreciation policies (shorter useful lives, lower salvage values)

- Growing intangible asset values (successful R&D and brand-building)

- Strong free cash flow despite significant D&A expenses

Warning signs include:

- CapEx consistently below depreciation (potential asset degradation)

- Frequent impairment charges (poor acquisition decisions or strategic errors)

- Declining EBITDA despite stable net income (deteriorating operations masked by lower D&A)

Valuation Adjustments

When comparing companies or calculating intrinsic value:

Normalize for different depreciation policies: Companies using aggressive (fast) depreciation will show lower earnings than peers using conservative (slow) depreciation, all else equal.

Add back amortization of acquisition intangibles: Some investors exclude amortization of acquisition-related intangibles when calculating “normalized” earnings, arguing these are artifacts of purchase accounting rather than economic costs.

Consider replacement CapEx: Estimate the capital spending required to maintain current operations, which may differ from reported depreciation.

Tax Efficiency for Business Owners

If you own a business or are considering entrepreneurship:

Maximize Section 179 deductions: Take advantage of immediate expensing for qualifying assets to reduce current-year taxes.

Time asset purchases strategically: Buying depreciable assets before year-end can generate valuable tax deductions.

Structure acquisitions carefully: How you allocate purchase price between asset categories affects your depreciation and amortization schedule—and therefore your tax bill.

Keep detailed records: Proper documentation of asset costs, useful lives, and depreciation calculations is essential for tax compliance and audit defense.

Practical Tips for Applying Your Knowledge

Now that you understand amortization vs depreciation, here are actionable ways to use this knowledge:

For Investors

- Review the cash flow statement: Always compare operating cash flow to net income. Large differences often stem from depreciation and amortization.

- Calculate the CapEx ratio: Divide capital expenditures by depreciation expense. Ratios consistently below 1.0 may indicate underinvestment.

- Examine footnotes: Companies disclose their depreciation methods and useful life assumptions in financial statement notes. Conservative assumptions suggest quality management.

- Use multiple valuation metrics: Don’t rely solely on P/E ratios. Consider EV/EBITDA, P/FCF, and other metrics that account for D&A differences.

- Compare within industries: Depreciation and amortization practices vary by sector, so compare companies to industry peers rather than the broader market.

For Business Owners

- Optimize tax strategy: Work with your accountant to maximize Section 179 deductions and bonus depreciation where applicable.

- Maintain detailed records: Document asset purchases, improvements, and disposals to support depreciation calculations and defend against audits.

- Plan major purchases: Time-significant asset acquisitions to maximize tax benefits, considering both current-year deductions and multi-year depreciation schedules.

- Separate land from buildings: When purchasing real estate, properly allocate costs to maximize the depreciable basis.

- Consider lease vs. buy: Factor in depreciation benefits when deciding whether to lease or purchase major assets.

For Students and Career Builders

- Master the basics: Ensure you thoroughly understand straight-line depreciation and amortization before moving to advanced methods.

- Practice with real statements: Download annual reports from public companies and trace depreciation and amortization through the financial statements.

- Understand industry differences: Study how D&A varies across sectors—manufacturing vs. technology vs. services—to build contextual knowledge.

- Learn tax implications: Familiarize yourself with Section 179, bonus depreciation, and MACRS rules, as these drive real business decisions.

- Connect to valuation: Practice adjusting earnings for D&A differences when comparing companies or calculating intrinsic value.

The Bigger Picture: Why These Concepts Matter for Financial Literacy

Understanding amortization vs depreciation connects to broader financial literacy in several important ways.

Connecting to Personal Finance

While most individuals don’t depreciate personal assets for tax purposes, the underlying concepts apply:

Car depreciation: Your vehicle loses value over time, just like business equipment. Understanding this helps you make better purchasing decisions and negotiate effectively.

Home improvements: Certain home improvements can be depreciated if you rent out property, creating tax benefits for passive income strategies.

Small business opportunities: If you freelance or run a side business, understanding depreciation can significantly reduce your tax bill.

Building Investment Acumen

Mastering these concepts strengthens your overall investment analysis skills:

Reading financial statements: You can’t truly understand a company’s finances without grasping D&A.

Identifying value: Companies with high D&A relative to cash flow may be undervalued by investors who focus only on reported earnings.

Understanding market volatility: When markets react to earnings reports, knowing how D&A affects those numbers helps you separate signal from noise.

Evaluating Business Models

Different business models rely on different asset types:

Asset-light businesses (software, consulting) have minimal depreciation but may have significant amortization from intellectual property.

Capital-intensive businesses (manufacturing, utilities) have substantial depreciation and require ongoing investment to maintain competitiveness.

Hybrid models (telecommunications, healthcare) combine significant tangible and intangible assets, requiring careful analysis of both.

Understanding these patterns helps you evaluate what moves the stock market and identify attractive investment opportunities.

Advanced Considerations: Going Deeper

For those who want to take their understanding to the next level, consider these advanced topics:

Impairment vs. Depreciation/Amortization

Impairment is a sudden write-down when an asset’s fair value falls below its book value. Unlike systematic depreciation or amortization, impairments are:

- Irregular: Recorded only when triggered by events or conditions

- Large: Often involves significant one-time charges

- Irreversible: Under U.S. GAAP, impairment losses generally can’t be reversed

Frequent impairments may signal poor capital allocation decisions or deteriorating business conditions.

Component Depreciation

Under IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards), companies must separately depreciate significant components of an asset with different useful lives. For example, an aircraft might be divided into:

- Airframe (25-year life)

- Engines (15-year life)

- Interior (7-year life)

This creates more accurate depreciation but adds complexity. U.S. GAAP doesn’t require component depreciation, though companies may choose to use it.

Accelerated Depreciation and Tax Strategy

Accelerated depreciation methods (declining balance, sum-of-years-digits, MACRS) provide larger deductions in early years. This creates:

Tax deferral benefits: Pay less tax now, more later (assuming tax rates remain constant)

Time value advantages: Money saved on taxes today can be invested to earn returns

Potential rate arbitrage: If tax rates decrease, you save at higher rates and pay back at lower rates

Sophisticated tax planning leverages these timing differences to minimize the present value of tax obligations.

Purchase Price Allocation in Acquisitions

When one company acquires another, the purchase price must be allocated among:

- Tangible assets (depreciated)

- Identifiable intangible assets (amortized)

- Goodwill (tested for impairment, not amortized)

This allocation significantly affects future earnings. For example, allocating more to short-lived intangibles increases amortization expense, reducing reported profits but potentially creating tax benefits.

Conclusion: Mastering Amortization vs Depreciation

Understanding the difference between amortization vs depreciation is more than an accounting technicality—it’s a fundamental skill for anyone serious about investing, business ownership, or financial literacy.

To recap the key distinctions:

- Depreciation applies to tangible assets; amortization applies to intangible assets

- Both spread asset costs over useful life, matching expenses to revenue generation

- Neither represents actual cash leaving the company—they’re accounting allocations

- Different calculation methods exist, with the straight-line being the most common for both

- Tax rules often differ from financial reporting rules, creating strategic opportunities

- Understanding these concepts helps investors see beyond reported earnings to true cash generation

Your Next Steps

Ready to put this knowledge into action? Here’s what to do next:

- Review your portfolio: Look at the financial statements of companies you own or are considering. Calculate their CapEx-to-depreciation ratios and examine their D&A trends.

- Practice analysis: Download annual reports from companies in different industries. Compare how depreciation and amortization affect their reported results.

- Explore related concepts: Deepen your understanding by learning about how the stock market works and investment fundamentals.

- Consider tax planning: If you own a business or are self-employed, consult with a tax professional about optimizing your depreciation strategy.

- Keep learning: Financial literacy is a journey, not a destination. Continue building your knowledge with resources on smart financial moves and investment strategies.

Remember: The most successful investors aren’t those who know every complex formula—they’re those who understand fundamental concepts deeply and apply them consistently. Amortization and depreciation are two of those foundational concepts that, once mastered, will serve you throughout your investing career.

Whether you’re analyzing potential investments, running a business, or simply trying to understand financial news more clearly, you now have the tools to see beyond surface-level numbers and understand the economic reality they represent.

References and Additional Resources

For further reading and authoritative sources on amortization and depreciation:

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC): – Access public company financial statements and accounting guidance

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB): Authoritative source for U.S. GAAP accounting standards

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS): Publication 946: How to Depreciate Property

- Investopedia: Comprehensive definitions and examples of accounting concepts

- CFA Institute: Professional standards and educational resources for investment analysis

The main difference is the type of asset being expensed. Depreciation applies to tangible (physical) assets like buildings, vehicles, and equipment, while amortization applies to intangible assets like patents, copyrights, and trademarks. Both spread the asset’s cost over its useful life, but depreciation often includes salvage value and multiple calculation methods, whereas amortization typically uses straight-line with no residual value.

Under current U.S. GAAP, goodwill is neither amortized nor depreciated. Since 2001, goodwill has been subject to annual impairment testing instead of systematic amortization. If the fair value of a reporting unit falls below its book value (including goodwill), an impairment charge is recorded. However, private companies can elect to amortize goodwill over 10 years under an accounting alternative.

No, depreciation is a non-cash expense. While it reduces reported net income on the income statement, no cash actually leaves the company during the depreciation process. The cash was spent when the asset was originally purchased. This is why depreciation is added back to net income when calculating operating cash flow on the statement of cash flows.

The straight-line depreciation formula is: (Asset Cost – Salvage Value) / Useful Life = Annual Depreciation. For example, if you purchase equipment for $50,000, expect it to last 10 years, and estimate a salvage value of $5,000, your annual depreciation would be ($50,000 – $5,000) / 10 = $4,500 per year.

EBITDA stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. It measures a company’s operating performance before accounting for financing decisions, tax environments, and non-cash expenses. Investors use EBITDA to compare companies with different capital structures and depreciation policies, though it has limitations because it doesn’t reflect actual cash flow or capital requirements.

No, land cannot be depreciated. The IRS considers land to have an indefinite useful life, so it doesn’t wear out or become obsolete. However, land improvements (like parking lots, fences, or landscaping) can be depreciated separately from the land itself. When purchasing property, you must allocate the cost between land (non-depreciable) and buildings/improvements (depreciable).

When an asset is fully depreciated, its book value equals its salvage value (or zero if no salvage value was estimated). The asset remains on the balance sheet at this value until it’s disposed of or retired. No further depreciation expense is recorded, even if the asset continues to be used productively. Many companies operate fully depreciated assets for years beyond their estimated useful lives.

Amortization reduces reported earnings but doesn’t affect cash flow, which can create valuation opportunities. Companies with high amortization relative to peers may appear less profitable on a P/E ratio basis, even though their cash generation is strong. Savvy investors often focus on cash flow metrics or add back acquisition-related amortization when valuing these companies, potentially identifying undervalued opportunities.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. Depreciation and amortization rules are complex and vary based on jurisdiction, asset type, and specific circumstances. Always consult with qualified professionals—including certified public accountants, tax advisors, and financial planners—before making decisions that affect your financial situation. Tax laws change frequently, and the information provided here reflects general principles that may not apply to your specific situation. Past performance of investments does not guarantee future results.

About the Author

Written by Max Fonji — With over a decade of experience in financial education and investment analysis, Max is your go-to source for clear, data-backed investing education. As the founder of TheRichGuyMath.com, Max has helped thousands of readers build financial literacy and make smarter investment decisions. His mission is to demystify complex financial concepts and empower readers to take control of their financial futures.