What Is the Purchasing Power of the Dollar?

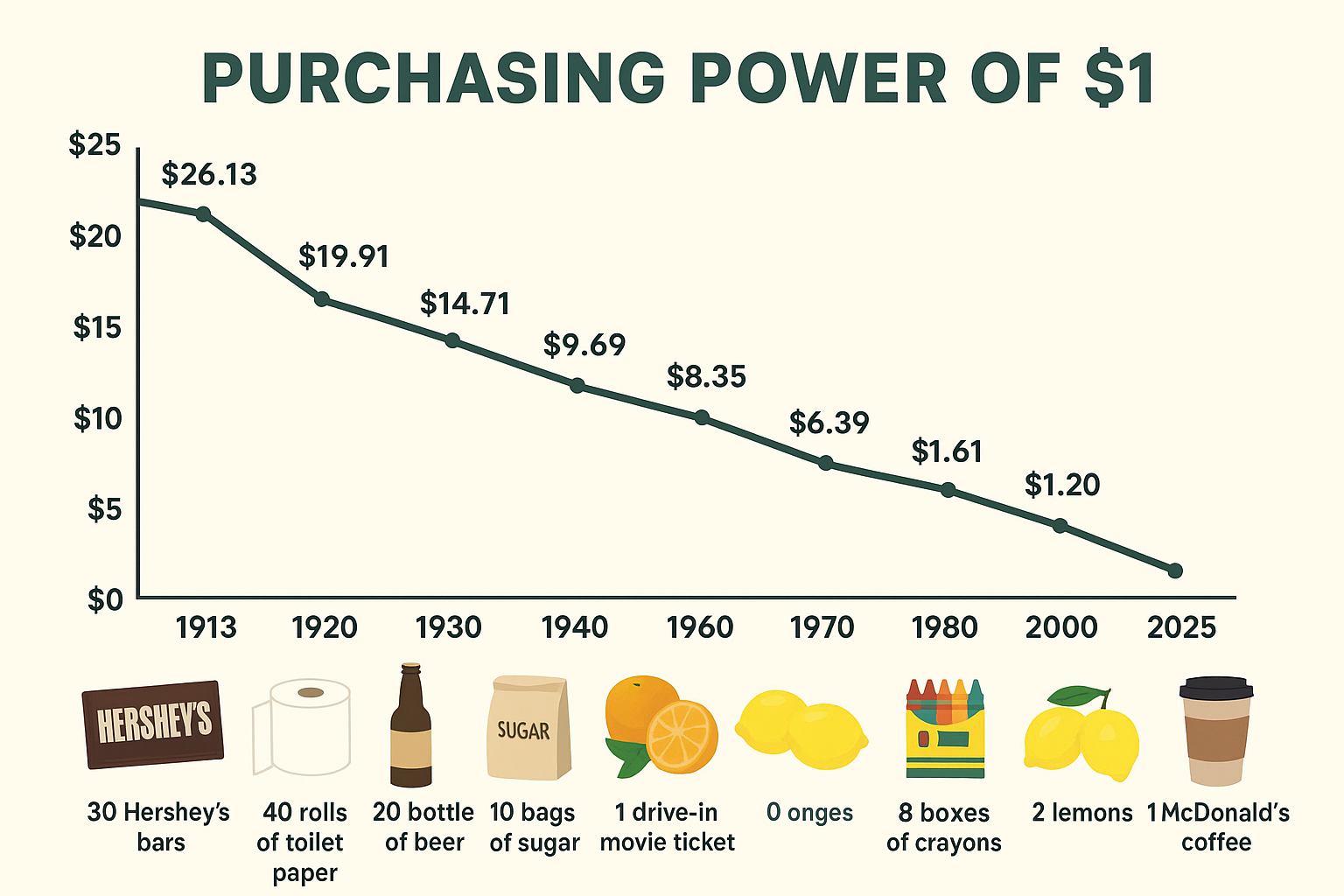

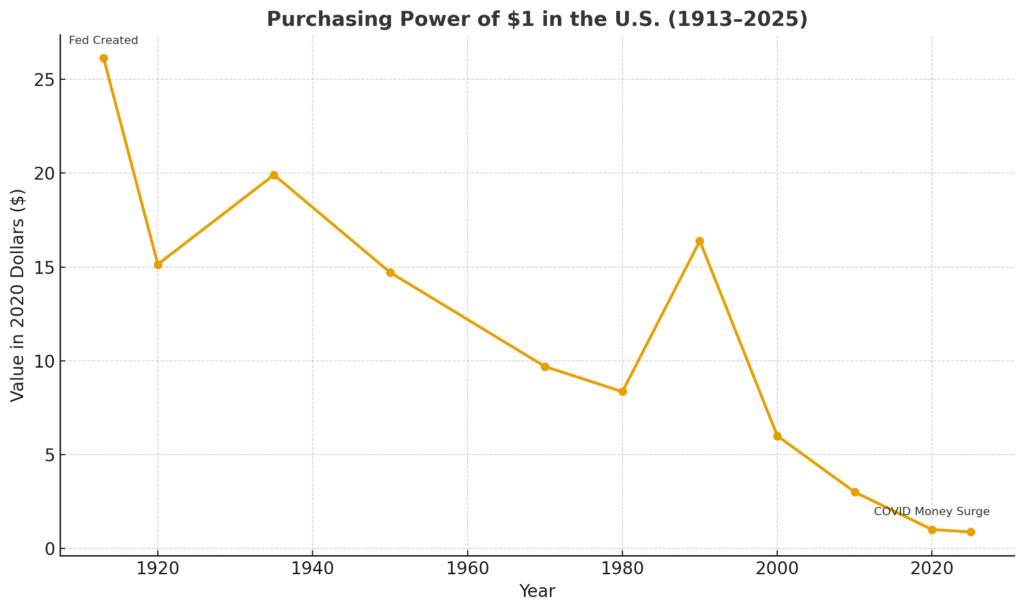

The purchasing power of the U.S. dollar measures how many goods and services $1 can buy at a given time. Over the past century, inflation and changes in monetary policy have sharply reduced the value of money.

For example, in 1913, $1 could buy 30 Hershey’s chocolate bars. By 2020, that same dollar was only enough for a small cup of McDonald’s coffee.

Understanding how the dollar has lost over 90% of its value since the creation of the Federal Reserve is essential for anyone concerned about long-term financial planning, investing, or retirement.

A Century of Declining U.S. Dollar Value

The U.S. dollar hasn’t always been as weak as it is today. Its history reflects global wars, recessions, economic booms, and major policy shifts.

1913 – The Federal Reserve Act

Congress created the Federal Reserve to stabilize the financial system and manage the money supply. That same year, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was launched to track inflation.

At this time, $1 had the same purchasing power as $26 today.

1929 – The Great Depression

After the stock market crash, the U.S. experienced deflation, which temporarily increased the dollar’s buying power. Prices for goods fell, but so did wages and employment.

1933 – End of Private Gold Ownership

President Franklin D. Roosevelt banned U.S. citizens from holding gold, forcing them to trade it for dollars. This weakened the link between the dollar and precious metals.

1944 – Bretton Woods Agreement

The dollar was pegged to gold at $35 per ounce and became the world’s reserve currency, cementing U.S. dominance in global trade.

1971 – Nixon Ends the Gold Standard

President Richard Nixon “closed the gold window”, making the dollar a fiat currency backed only by government trust. From this point, inflation accelerated.

1980s – Inflation Peaks

After years of oil shocks and loose fiscal policies, annual inflation peaked at 13.5% in 1980. Paul Volcker, then Federal Reserve Chair, raised interest rates above 20% to tame it.

2008 – Quantitative Easing (QE)

In response to the global financial crisis, the Fed launched QE, printing trillions of dollars to buy bonds and stabilize the economy.

2020 – Pandemic Money Surge

The COVID-19 crisis led to a 20% increase in the money supply within one year. By 2021–2022, inflation reached 40-year highs.

Purchasing Power Over Time: What $1 Bought

| Year | Equivalent Value of $1 | Example Purchase |

|---|---|---|

| 1913 | $26.13 | 30 Hershey’s bars |

| 1920 | $15.14 | 40 rolls of toilet paper |

| 1935 | $19.91 | 20 bottles of beer |

| 1950 | $14.71 | 10 bottles of Coca-Cola |

| 1970 | $9.69 | 10 bags of sugar |

| 1980 | $8.35 | 1 drive-in movie ticket |

| 1990 | $16.39 | 17 oranges |

| 1997 | $2.28 | 8 boxes of crayons |

| 2008 | $1.61 | 2 lemons |

| 2020 | $1.00 | 1 McDonald’s coffee |

| 2025* | ~$0.87 | Less than 1 cup of coffee |

(Estimate based on BLS CPI data and 2024 inflation averages.)

Formula: How to Calculate the Real Value of the U.S. Dollar

The inflation-adjusted value of money is calculated using the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Formula:

Real Value = (Nominal Value / CPI (Base Year)) × CPI (Target Year)

Example:

CPI in 1920 = 20, CPI in 2020 = 260

$1 (1920) = (1 / 20) × 260 = $13 (2020)

This means $1 in 1920 had the same buying power as $13 in 2020.

Why Does the U.S. Dollar Lose Value?

Several key drivers explain the dollar’s long-term decline:

- Inflation – As prices rise, each dollar buys less.

- Money Supply Growth – Printing more money reduces its scarcity and value.

- Interest Rates – Low rates fuel spending and inflation, while high rates strengthen the dollar.

- Government Debt – The more debt the U.S. issues, the more dollars flood the system.

- Global Confidence – The dollar is still the world’s reserve currency, but overreliance weakens its stability.

Advantages & Disadvantages of a Declining U.S. Dollar

Advantages

- Makes U.S. exports more competitive.

- Reduces the real value of government and consumer debt.

- Encourages asset price growth (stocks, real estate).

Disadvantages

- Shrinks household purchasing power.

- Erode’s savings are held in cash.

- Raises the cost of living (housing, food, healthcare).

- It can weaken global trust in the U.S. economy.

Case Study: Coffee Prices as a U.S. Dollar Indicator

In the 1960s, 25 cents bought a cup of coffee at a diner. Today, that same cup costs $2 to $5, depending on location.

That’s an 800%+ increase in 60 years, a simple but powerful example of how the dollar loses value over time.

Investor & Everyday Use Cases U.S. Dollar

For Investors

- Inflation Hedges: Gold, silver, commodities, and real estate protect against a weaker dollar.

- Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS): Bonds that rise with inflation.

- Stocks: Equities generally outpace inflation over long time horizons.

For Everyday People

- Save Smarter: Keep emergency funds, but don’t hold excessive cash.

- Invest Early: Compounding returns help offset inflation.

- Budget with Inflation in Mind: Expect prices to rise over time.

FAQs About the Dollar’s Purchasing Power

Because of inflation, government spending, and monetary policy decisions that increased the money supply.

Yes, during deflationary periods like the Great Depression (1930s).

Hard assets (gold, real estate), TIPS, and diversified investments.

Over 90% of its purchasing power.

It remains the world’s reserve currency, but faces competition from the euro, yuan, and digital assets.

Other Link Suggestions

Sources Link

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics – CPI Data

- Federal Reserve – Monetary Policy

- Morningstar – Inflation Investing

- St. Louis Fed – Money Supply (M2)

Bottom Line

The U.S. dollar has lost over 90% of its purchasing power since 1913. What once bought groceries now buys a cup of coffee.

For savers and investors, the lesson is clear: cash loses value over time. The best defense is smart financial planning, investing in assets that grow faster than inflation.

Ready to learn how to beat inflation? Explore The Rich Guy Math for practical guides on wealth building, investing, and protecting your money.