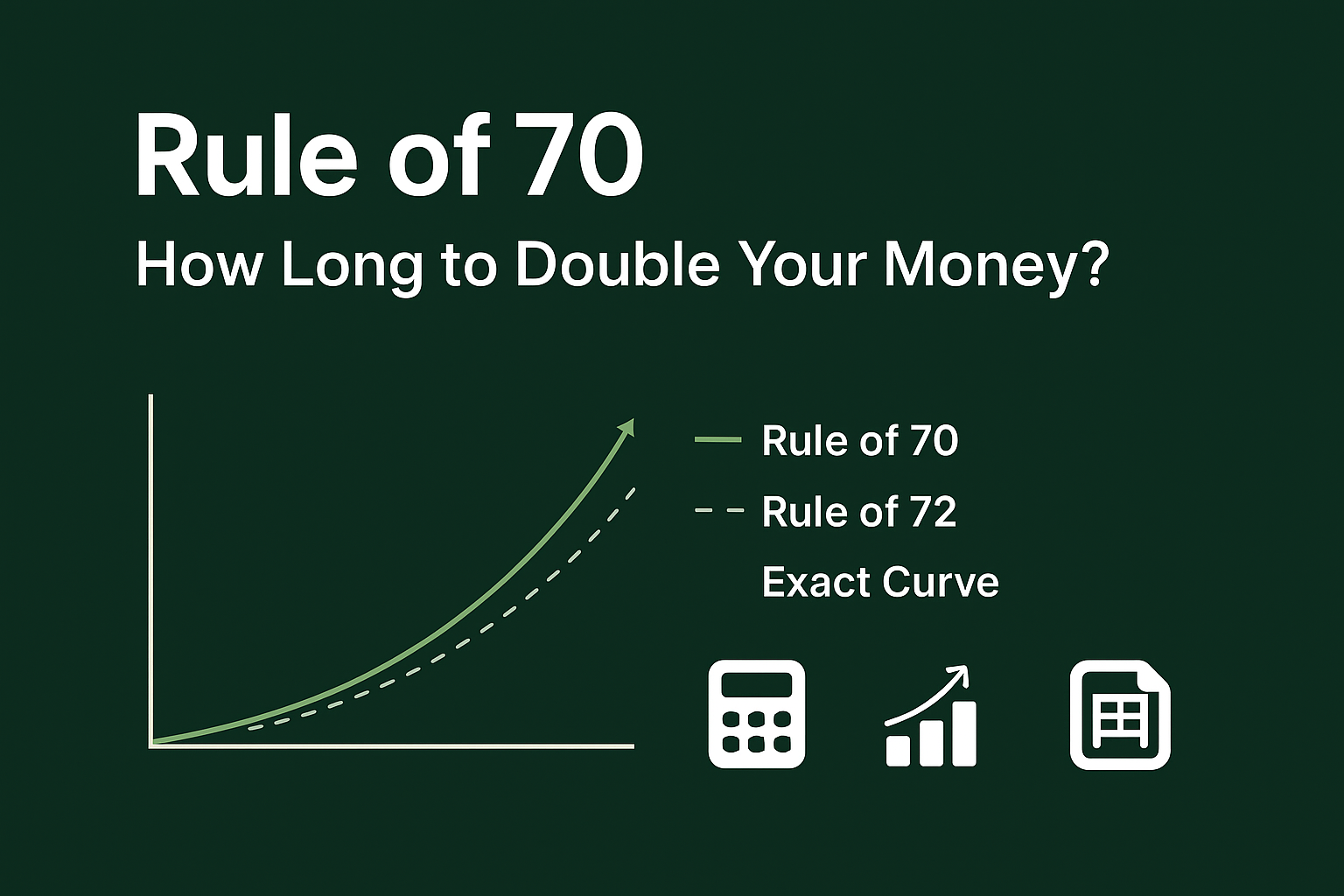

Rule of 70 is a quick mental shortcut: years to double ≈ 70 ÷ growth rate (%). Use it to estimate when your investment, inflation erosion, or any steadily growing quantity will double. But it’s only an approximation. In this article, you’ll learn:

- How the Rule of 70 works (and its math behind it)

- When it’s a good approximation and when it breaks down

- Side-by-side comparison vs Rule 72 and the exact formula

- Real investor examples (stocks, debt, inflation)

- A free downloadable spreadsheet + embedded calculator

- Common pitfalls, limitations, and FAQs

If you prefer precision over a mental shortcut, scroll to the “Tools” section where you can use the exact formula or download a spreadsheet. Investopedia

What is the Rule of 70?

The Rule of 70 is a rough formula:

Years to double ≈ 70 ÷ r,

where r = annual growth rate in percent (for example, 7 means 7%).

Example: If your investment grows at 5% per year, then

70÷5=1470 ÷ 5 = 1470÷5=14 years (approximate).

This gives you a fast back-of-the-envelope doubling estimate. It works well for moderate rates (3% to 10%), with a small error. But it’s not exact. Wikipedia

The math behind it (exact formula & alternatives)

If you want precision, the exact doubling time formula is:

t = ln(2) / ln(1+r)

Here, r is the decimal growth rate (e.g., 0.07 for 7%). Because ln(2) ≈ 0.693, people sometimes use 69.3 instead of 70 or 72 for their mental math shortcuts.

- Rule of 69.3 is better when compounding is continuous or extremely frequent.

- The rule of 72 is popular because 72 is divisible by many small integers (useful with rates like 8, 9, 12).

Each rule is just an approximation to the true exponential formula.

Comparison: Rule of 70 vs Rule of 72 vs Exact

Here’s a comparison table showing how the approximations perform vs the exact formula:

| Rate (%) | Exact doubling time | Rule of 70 | Rule of 72 | Rule of 69.3 | % Error using Rule 70 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 69.66 yrs | 70.00 | 72.00 | 69.30 | +0.49% |

| 2% | 35.00 yrs | 35.00 | 36.00 | 34.65 | 0.00% |

| 5% | 14.21 yrs | 14.00 | 14.40 | 13.86 | –1.45% |

| 7% | 10.25 yrs | 10.00 | 10.29 | 9.90 | –2.39% |

| 10% | 7.27 yrs | 7.00 | 7.20 | 6.93 | –3.75% |

| 20% | 3.80 yrs | 3.50 | 3.60 | 3.465 | –7.94% |

Insights:

- At low rates (1%–3%), the Rule of 70 is extremely accurate.

- In the 5%–8% range (typical long-term stock returns), the error is modest (1–3%).

- At high rates (>=20%), the error becomes significant, so you should favor the exact formula or model with compounding.

When the Rule of 70 works well

You’ll see the Rule of 70 used in situations like:

- Investments: to estimate how long your portfolio might take to double.

- Inflation: to estimate when purchasing power halves (e.g., 3.5% inflation gives ~20 years for value to halve).

- Economic growth/population: to approximate a doubling of GDP, population, or revenues.

Investor example: Suppose a stock index returns ~7% per year. The Rule of 70 gives ~10 years to double. Of course, actual returns vary year to year, so use the average annual rate or a more precise model for planning. Corporate Finance

Debt example: If you carry credit card debt at 20% interest and make no payments, your balance will roughly double in 70 ÷ 20 = 3.5 years. That helps highlight how dangerous high‐rate debt is.

Limitations & real-world adjustments

Fluctuating rates

The Rule of 70 assumes a steady growth rate. Real returns jump, dip, and compound unevenly. Use it only for estimates, not guarantees.

Compounding frequency matters

If interest compounds more often (monthly, daily, continuously), the true formula diverges slightly from simple rules. For high-frequency compounding, the Rule of 69.3 (or exact formula) is more accurate.

Fees, taxes & withdrawals

Your net effective rate (after fees, taxes, inflation) is what matters. Subtract those from the gross rate before applying any rule.

Negative or zero growth

If growth is negative, you can flip the idea to estimate halving time:

Years to half ≈ 70 / rate (%)

E.g., a –4% rate → 70 ÷ 4 = 17.5 years to drop in half.

Tools: Calculator & Downloadable Spreadsheet

Try this interactive calculator:

Enter any annual rate and see the results for:

- Exact doubling time (via ln formula)

- Rule of 70 estimate

- Rule of 72 estimate

- Percent error of the Rule of 70

Below the calculator, you’ll find a free downloadable spreadsheet (.xlsx or .csv) with:

- Preloaded formulas

- The comparison table above

- Sample scenarios (stock returns, inflation, debt)

You can import that into Excel or Google Sheets and tinker with your own rates.

Rule of 70 Calculator

| Exact doubling time | — |

| Rule of 70 | — |

| Rule of 72 | — |

| Rule of 69.3 | — |

| % Error (70) | — |

Tip: use a net-of-fees, after-tax rate for planning.

Download the free Rule of 70 spreadsheet.

Summary

The Rule of 70 is a fast, useful mental shortcut to estimate doubling times. It’s not perfect, but it’s easy to use and often “good enough” for casual planning. Use it to compare alternatives, sanity-check assumptions, or teach others.

For precise financial planning, especially over long time frames, always cross-check with the exact formula or use a modeling tool that incorporates compounding frequency, volatility, fees, and taxes.

Yes, but only on average CAGR. It loses accuracy with highly volatile returns—use Monte Carlo or historical simulations for serious planning.

Both are useful. The Rule of 72 often gives slightly better accuracy in the 6–9% range. Use whichever is easier or more familiar.

Because 70 is round and easy to divide mentally. 69.3 ties to ln(2), while 72 is often used because it’s convenient for dividing by rates like 8, 9, 12.

More frequent compounding (monthly, daily, continuous) slightly changes the outcome. In that case, use Rule of 69.3 or the exact formula for better precision.

They reduce your net growth rate. Subtract expected fees & taxes first, then apply the rule or formula.

Yes, it works for any steady percentage growth. But real-world growth is volatile, so use it with caution.

For rates between 3%–8%, error is often <3%. Once rates exceed ~15%, the error can grow into double digits, making the Rule of 70 less reliable.

Author Bio:

Max Fonji is the founder of TheRichGuyMath.com, a site dedicated to investor education, financial tools, and SEO-driven content that helps readers make smart money decisions. With over 8 years of writing and investing experience, I blend clear explanation, math rigor, and hands-on technique so you get both insight and usable tools.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes and is not financial advice. Always consult a qualified financial adviser before making investment decisions. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.