When you sign a loan document or open a savings account, the percentage you see printed in bold letters represents the nominal interest rate, the stated cost of borrowing, or the advertised return on your money. But here’s what most people miss: that number tells only part of the story.

The nominal interest rate is the raw, unadjusted figure that appears on financial contracts before accounting for inflation’s erosive effects or the compounding magic that can multiply your wealth. Understanding this fundamental concept unlocks the math behind money and reveals why two investments with identical nominal rates can deliver vastly different real returns. This knowledge forms the foundation of evidence-based investing and smart borrowing decisions.

In 2025, with interest rates fluctuating and inflation remaining a critical concern, distinguishing between nominal and real returns has never been more important for wealth building. This guide breaks down the formulas, demonstrates practical calculations, and shows you exactly how nominal interest rates impact your financial decisions.

Key Takeaways

- The nominal interest rate is the stated percentage on loans and investments before adjusting for inflation or compounding effects

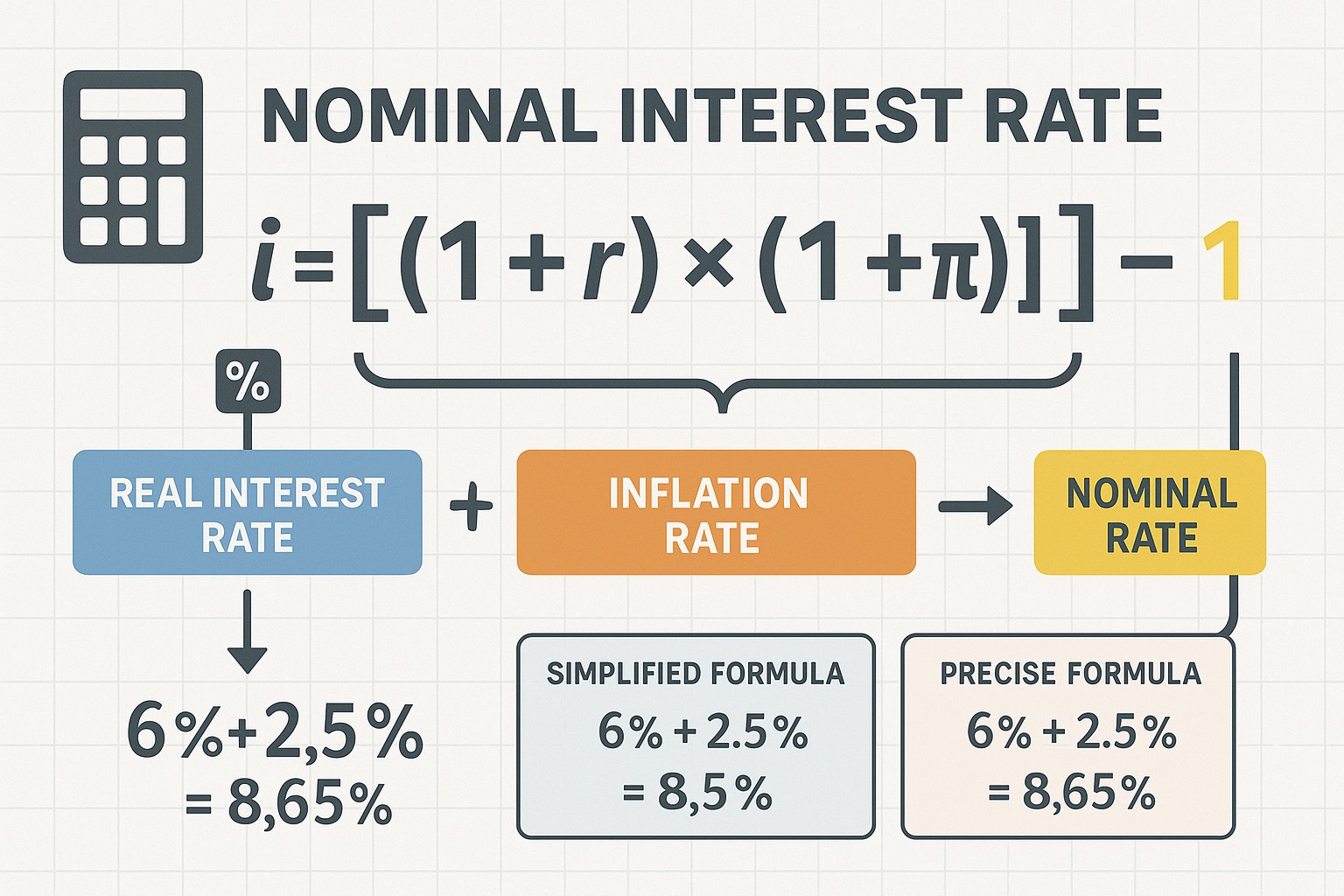

- The primary formula connects nominal rate (i), real rate (r), and inflation (π): i = [(1 + r) × (1 + π)] – 1

- Nominal rates differ from effective rates because they don’t account for compounding frequency within a year

- Inflation erodes purchasing power, making the real interest rate the true measure of investment growth

- Understanding this distinction prevents costly financial mistakes and improves investment decision-making

What Is the Nominal Interest Rate?

The nominal interest rate represents the percentage cost of borrowing money or the percentage return on an investment as stated in a contract, without any adjustments for inflation or compounding periods.

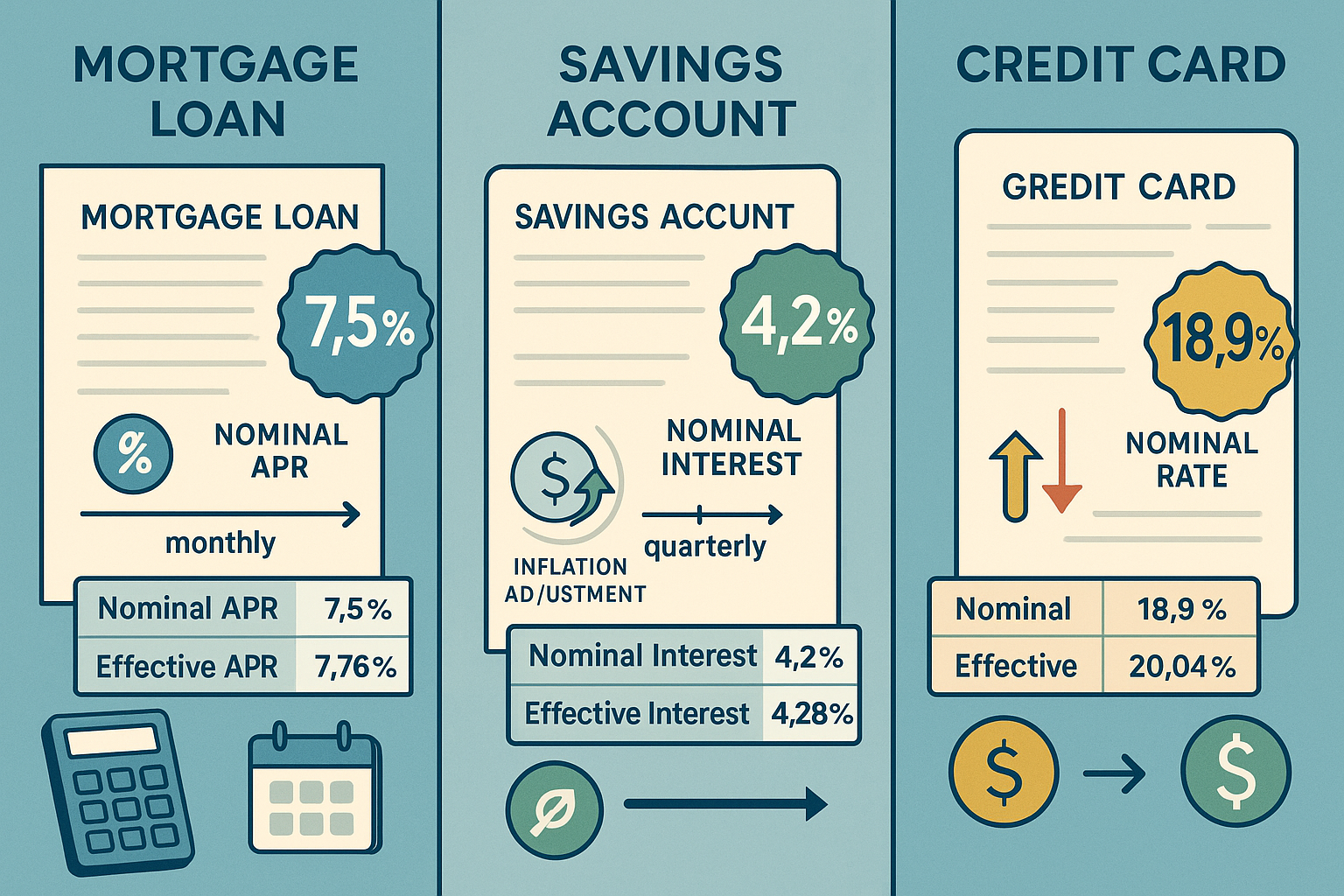

Think of it as the “sticker price” of money. When a bank advertises a 5% annual percentage rate (APR) on a personal loan, that 5% is the nominal rate. When a certificate of deposit promises 4.2% annual returns, that’s also a nominal rate. These figures appear on every financial document you’ll encounter—from mortgage agreements to credit card statements to bond certificates.

The nominal interest rate serves three primary functions:

- Standardized communication between lenders and borrowers

- Legal documentation of contractual obligations

- Baseline comparison across different financial products

The term “nominal” comes from the Latin word for “name”—it’s literally the “named” or “stated” rate. This distinguishes it from the real interest rate, which adjusts for inflation’s impact on purchasing power, and the effective interest rate, which accounts for compounding frequency.

“The nominal rate is what you see. The real rate is what you get. The difference between them determines whether you’re building wealth or losing ground to inflation.” — Financial literacy principle

Financial institutions must disclose nominal rates by law, making them the most visible metric in consumer finance. However, this visibility creates a common trap: focusing solely on nominal rates without understanding their limitations leads to poor financial decisions.

The Math Behind Nominal Interest Rate: Core Formulas

The Fisher Equation: Connecting Nominal, Real, and Inflation

The most precise formula for calculating nominal interest rate comes from economist Irving Fisher, who identified the mathematical relationship between these three variables:

i = [(1 + r) × (1 + π)] – 1

Where:

- i = nominal interest rate

- r = real interest rate (return after inflation)

- π = inflation rate (percentage increase in prices)

This equation reveals a critical insight: the nominal rate must compensate lenders for both the real return they expect and the purchasing power lost to inflation.

Let’s demonstrate with concrete numbers. Suppose a lender wants a 6% real return (r = 0.06) and expects 2.5% inflation (π = 0.025):

i = [(1 + 0.06) × (1 + 0.025)] – 1

i = [1.06 × 1.025] – 1

i = 1.0865 – 1

i = 0.0865 or 8.65%

The nominal rate must be 8.65% to deliver a 6% real return when inflation runs at 2.5%.

The Simplified Approximation Formula

For quick calculations when inflation remains moderate (below 5-7%), financial professionals use a simplified version:

i ≈ r + π

Using the same example:

i ≈ 0.06 + 0.025 = 0.085 or 8.5%

The difference between 8.65% (precise) and 8.5% (approximation) is only 0.15 percentage points, negligible for most practical purposes. However, as inflation rises, this gap widens. At 10% inflation with a 6% real rate, the precise formula yields 16.6% while the approximation gives 16%, a 0.6 percentage point difference that matters for large investments.

Simple Interest Nominal Rate Calculation

When dealing with simple interest (interest that doesn’t compound), calculate the nominal rate using:

R = I / (P × T)

Where:

- R = nominal interest rate

- I = total interest earned or paid

- P = principal amount

- T = time period in years

Example: You invest $5,000 and receive $750 in interest after 3 years.

R = $750 / ($5,000 × 3)

R = $750 / $15,000

R = 0.05 or 5% per year

This formula works for simple interest calculations, but becomes inadequate when compound interest enters the equation.

Nominal APR from Periodic Rates

Credit cards and some loans quote periodic rates (monthly, quarterly) that compound throughout the year. Convert these to nominal APR:

Nominal APR = i × n

Where:

- i = periodic interest rate

- n = number of periods per year

Example: A credit card charges 1.5% monthly interest.

Nominal APR = 0.015 × 12 = 0.18 or 18% APR

This nominal APR of 18% understates the true cost because it ignores compounding. The effective annual rate (EAR) would be higher: (1.015)^12 – 1 = 19.56%. This distinction between nominal and effective rates costs consumers billions annually in underestimated borrowing costs.

Nominal vs Real Interest Rate: The Inflation Factor

The relationship between nominal and real interest rates determines whether your money grows or shrinks in purchasing power. This distinction separates financially literate investors from those who chase impressive-looking numbers that deliver disappointing results.

Calculating Real Interest Rate from Nominal

Rearrange the Fisher equation to isolate the real rate:

r = [(1 + i) / (1 + π)] – 1

Or use the approximation:

r ≈ i – π

Scenario 1: Positive Real Return

You hold a bond paying 7% nominal interest (i = 0.07) while inflation runs at 3% (π = 0.03).

Precise calculation:

r = [(1.07) / (1.03)] – 1 = 1.0388 – 1 = 3.88% real return

Approximation:

r ≈ 0.07 – 0.03 = 4% real return

Your purchasing power increases by approximately 3.88% annually—you’re building real wealth.

Scenario 2: Negative Real Return

You earn 2% nominal interest in a savings account (i = 0.02) while inflation surges to 6% (π = 0.06).

r = [(1.02) / (1.06)] – 1 = 0.9623 – 1 = -3.77% real return

Despite earning interest, your purchasing power declines by 3.77% annually. You’re losing money in real terms, a common trap for conservative savers during inflationary periods.

The Inflation Erosion Effect

Consider $10,000 invested at different nominal rates with 4% inflation:

| Nominal Rate | Real Return | Value After 10 Years (Nominal) | Purchasing Power (Real) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2% | -1.92% | $12,190 | $8,240 |

| 4% | 0% | $14,802 | $10,000 |

| 6% | 1.92% | $17,908 | $12,100 |

| 8% | 3.85% | $21,589 | $14,570 |

The 2% nominal rate actually destroys 18% of your purchasing power over a decade. The 4% nominal rate merely preserves your wealth without growth. Only rates exceeding inflation create genuine wealth accumulation.

This mathematical reality explains why building wealth requires investments that consistently outpace inflation. Stocks, real estate, and inflation-protected securities historically achieve this; traditional savings accounts rarely do.

Lender vs Borrower Perspective

From the lender’s viewpoint:

Nominal rates must exceed expected inflation to generate positive real returns. A bank lending at 5% nominal when expecting 3% inflation targets a 2% real profit margin.

From the borrower’s viewpoint:

Higher-than-expected inflation benefits borrowers at lenders’ expense. If you borrow at 5% nominal but inflation runs at 7%, your real borrowing cost is negative—you’re effectively being paid to borrow.

This dynamic drove wealth transfers during the 1970s inflation surge, when borrowers with fixed-rate mortgages at 6-8% nominal rates enjoyed negative real interest rates as inflation exceeded 10%. Conversely, the low-inflation 2010s favored lenders and punished borrowers who couldn’t refinance.

Understanding this relationship informs critical decisions: when to lock in fixed rates, when to choose variable rates, and how to position investments across the economic cycle.

Nominal vs Effective Interest Rate: The Compounding Difference

While the nominal-versus-real distinction addresses inflation, the nominal-versus-effective distinction addresses the compounding frequency source of confusion that costs investors and borrowers money.

Defining Effective Annual Rate (EAR)

The effective annual rate represents the true annual return or cost when accounting for intra-year compounding. It answers the question: “What single annual rate would produce the same result as this nominal rate compounded multiple times per year?”

Formula:

EAR = (1 + i/n)^n – 1

Where:

- i = nominal annual interest rate

- n = number of compounding periods per year

Practical Examples Across Compounding Frequencies

Example: 12% Nominal Rate with Different Compounding

| Compounding Frequency | Periods (n) | Periodic Rate | Effective Annual Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual | 1 | 12% | 12.00% |

| Semi-annual | 2 | 6% | 12.36% |

| Quarterly | 4 | 3% | 12.55% |

| Monthly | 12 | 1% | 12.68% |

| Daily | 365 | 0.0329% | 12.75% |

| Continuous | ∞ | — | 12.75% |

Monthly compounding calculation:

EAR = (1 + 0.12/12)^12 – 1

EAR = (1.01)^12 – 1

EAR = 1.1268 – 1 = 12.68%

A loan advertised at 12% nominal APR with monthly compounding actually costs 12.68% annually—a 0.68 percentage point difference. On a $100,000 loan over 30 years, this seemingly small gap costs thousands in additional interest.

Why This Matters for Borrowers and Investors

For borrowers:

Credit cards typically compound daily, making their effective rates substantially higher than nominal APRs. A card with 18% nominal APR and daily compounding has an effective rate of 19.72%—nearly 2 percentage points higher.

For investors:

Compound interest accounts with more frequent compounding periods generate higher returns from identical nominal rates. A 5% nominal rate compounded daily yields 5.13% effective return versus 5.00% with annual compounding, money to mathematical principles.

This explains why understanding continuous compounding becomes valuable for serious investors. The formula e^r – 1 (where e ≈ 2.71828) represents the mathematical limit of increasingly frequent compounding.

Regulatory Disclosure Requirements

The Truth in Lending Act requires lenders to disclose both nominal APR and effective APR (often called APY for Annual Percentage Yield on deposits) for this reason. However, many consumers focus only on the larger, more prominent nominal figure, missing the true cost or return.

When comparing financial products, always compare effective rates, not nominal rates. A mortgage at 6.5% nominal with monthly compounding may cost more than a mortgage at 6.6% nominal with annual compounding, depending on the specific terms.

Real-World Applications: Where Nominal Interest Rates Matter

Mortgages and Home Loans

When you shop for a mortgage, the nominal interest rate determines your monthly payment calculation. A $300,000 30-year fixed mortgage at 7% nominal (with monthly compounding) requires monthly payments of $1,996.

However, the total cost extends far beyond the nominal rate:

- Effective rate: 7.23% (accounting for monthly compounding)

- Real rate: Depends on inflation over 30 years

- Total interest paid: $418,527 over the loan life

If inflation averages 3% over those 30 years, your real borrowing cost drops to approximately 4% in inflation-adjusted terms. This makes fixed-rate mortgages attractive during rising inflation—you repay with progressively cheaper dollars while the nominal rate remains locked.

Savings Accounts and CDs

In 2025, high-yield savings accounts advertise nominal rates around 4-5%. A $10,000 deposit at 4.5% nominal with daily compounding yields:

Year 1 earnings: $459.90 (effective rate of 4.60%)

But if inflation runs at 3.5%, your real return is only 1.1%, barely outpacing purchasing power erosion. This demonstrates why conservative savers struggle to build substantial wealth through interest alone.

Certificates of deposit (CDs) lock in nominal rates for fixed terms. A 5-year CD at 5% nominal guarantees that rate regardless of future inflation changes. If inflation rises to 6%, you suffer negative real returns. If inflation falls to 2%, you enjoy 3% real returns. This interest rate risk represents a fundamental trade-off in fixed-income investing.

Credit Cards and Consumer Debt

Credit card nominal APRs typically range from 15% to 25%, with daily compounding that pushes effective rates 1-2 percentage points higher. A $5,000 balance at 18% nominal APR with minimum payments takes over 15 years to repay and costs more than $5,000 in interest.

The nominal rate on credit cards remains fixed in the contract, but the real cost to borrowers varies with inflation. During high inflation, the real cost of credit card debt decreases, though this provides little comfort given the astronomical nominal rates that still apply.

Strategic borrowers understand this: managing debt requires comparing nominal borrowing costs against nominal investment returns, while building long-term wealth requires focusing on real returns after inflation.

Bonds and Fixed-Income Securities

Corporate and government bonds quote nominal yields (coupon rates) that determine periodic interest payments. A $10,000 bond with a 6% nominal coupon pays $600 annually regardless of inflation or market conditions.

However, bond market prices fluctuate inversely with interest rates. When nominal rates rise from 6% to 7%, existing 6% bonds lose market value to compensate new buyers for the below-market coupon. This interest rate risk makes nominal rates critical for bond investors.

The relationship between nominal rates and bond prices follows this approximation:

Price change ≈ -Duration × Change in nominal yield

A bond with an 8-year duration loses approximately 8% of its value when nominal yields rise 1 percentage point. Understanding this math prevents costly mistakes in fixed-income portfolios.

Business Loans and Capital Allocation

Businesses evaluate nominal borrowing costs against nominal project returns when making capital allocation decisions. A company considering a $1 million expansion that generates 10% nominal returns can profitably borrow at any nominal rate below 10%.

However, sophisticated financial analysis adjusts both the borrowing cost and project returns for inflation to calculate real returns. A project with 10% nominal returns and 4% inflation delivers only 6% real returns. If the nominal borrowing cost is 7% with 4% inflation, the real borrowing cost is 3%, making the project viable in real terms despite the narrow nominal spread.

This analysis explains why businesses often increase borrowing during inflationary periods: the real cost of debt declines while nominal revenues (and the ability to service debt) increase with inflation.

Common Mistakes and Misconceptions

Mistake #1: Ignoring Inflation When Evaluating Returns

Many investors celebrate 6% returns without considering 5% inflation that reduces real gains to 1%. This nominal thinking creates an illusion of wealth building while purchasing power barely grows.

The fix: Always calculate real returns using r ≈ i – π. Compare investment options based on expected real returns, not nominal figures.

Mistake #2: Comparing Nominal Rates Across Different Compounding Frequencies

A savings account at 5% nominal with daily compounding outperforms a CD at 5.1% nominal with annual compounding. Comparing nominal rates alone misses this crucial difference.

The fix: Convert all rates to effective annual rates before comparing. Use the EAR formula: (1 + i/n)^n – 1.

Mistake #3: Assuming Fixed Nominal Rates Protect Against All Risks

A 30-year mortgage at 6% nominal provides certainty about payments but not about real costs. If inflation surges, you benefit. If deflation occurs, you suffer. Fixed nominal rates eliminate interest rate risk but not inflation risk.

The fix: Understand that fixed nominal rates lock in the nominal cost, not the real cost. Diversify across fixed and variable-rate instruments based on inflation expectations.

Mistake #4: Overlooking the Difference Between APR and APY

Banks advertise APR (nominal rate) for loans and APY (effective rate) for deposits, making loans appear cheaper and deposits more attractive than direct comparisons warrant.

The fix: Always compare APR to APR or APY to APY. Better yet, calculate the effective rate yourself using the compounding formula.

Mistake #5: Focusing Solely on Nominal Returns in Retirement Planning

Retirement calculators that project 7% nominal returns without adjusting for 3% inflation overestimate purchasing power by 40% over 30 years. This leads to underfunding retirement accounts.

The fix: Plan using real returns. If historical nominal stock returns are 10% and inflation averages 3%, use 7% real returns for retirement projections. This aligns with the 4% rule for sustainable withdrawal rates.

How to Use Nominal Interest Rate Knowledge in Financial Decisions

Strategy #1: Evaluate All Investments on a Real Return Basis

Before committing capital, calculate the expected real return:

- Identify the nominal return (interest rate, dividend yield, or expected appreciation)

- Estimate inflation over the investment period (use Federal Reserve targets or market-based measures)

- Calculate real return: r ≈ i – π

- Compare real returns across investment options

Example decision: Choose between a 5% nominal corporate bond and a 4% nominal Treasury Inflation-Protected Security (TIPS) when expecting 2.5% inflation.

- Corporate bond real return: 5% – 2.5% = 2.5%

- TIPS real return: 4% (inflation-protected, so the real return is guaranteed)

The TIPS provides more certainty despite the lower nominal rate, making it preferable for risk-averse investors.

Strategy #2: Time Your Borrowing Based on Nominal Rate Trends

When nominal rates are rising:

- Lock in fixed-rate debt before further increases

- Delay variable-rate borrowing if possible

- Consider refinancing existing variable-rate debt to fixed

When nominal rates are falling:

- Choose variable-rate debt to benefit from declining rates

- Refinance existing fixed-rate debt to lower rates

- Delay locking in long-term fixed rates

This timing strategy saved homeowners billions during the 2020-2021 refinancing wave when nominal mortgage rates dropped below 3%.

Strategy #3: Build a Balanced Portfolio Across Rate Environments

Different assets perform optimally under different nominal rate conditions:

Low nominal rate environment (0-3%):

- Stocks benefit from cheap borrowing costs

- Real estate appreciates with accessible financing

- Bonds offer minimal returns

- Cash loses purchasing power

Moderate nominal rate environment (3-6%):

- Balanced returns across asset classes

- Bonds provide a reasonable income

- Stocks face moderate borrowing costs

- Cash preservation becomes viable

High nominal rate environment (6%+):

- Bonds offer attractive yields

- Stocks face headwinds from expensive capital

- Cash and short-term instruments become competitive

- Real estate financing becomes challenging

Diversification across these scenarios protects against nominal rate uncertainty. This aligns with diversification principles that reduce portfolio volatility.

Strategy #4: Negotiate Better Terms by Understanding the Math

When borrowing, demonstrate knowledge of effective rates to negotiate better terms:

“I see this loan advertises 8% APR with monthly compounding, which creates an effective rate of 8.3%. Competitor X offers 8.2% APR with annual compounding, giving an effective rate of 8.2%. Can you match their effective rate?”

This approach signals sophistication and often yields concessions that save thousands over the loan life.

Strategy #5: Align Investment Horizon with Rate Type

Short-term goals (0-3 years): Focus on nominal rates with minimal inflation risk. High-yield savings and short-term CDs work well.

Medium-term goals (3-10 years): Balance nominal returns with inflation protection. Consider I-bonds, TIPS, and diversified stock/bond portfolios.

Long-term goals (10+ years): Prioritize real returns over nominal rates. Equities historically deliver 7% real returns despite varying nominal returns across decades.

This horizon-based approach prevents the mistake of chasing high nominal rates that fail to preserve purchasing power over your actual investment timeline.

The Relationship Between Nominal Rates and Economic Indicators

Federal Reserve Policy and Nominal Rates

The Federal Reserve influences nominal interest rates through its federal funds rate target—the overnight lending rate between banks. When the Fed raises this rate, nominal rates across the economy typically rise because:

- Banks increase prime rates (the basis for many consumer loans)

- Bond yields adjust to reflect higher short-term rates

- Mortgage rates rise as long-term borrowing costs increase

- Savings account rates eventually improve as banks compete for deposits

The Fed’s 2022-2023 rate hiking cycle demonstrated this mechanism. As the federal funds rate rose from near-zero to 5.25-5.50%, nominal mortgage rates climbed from 3% to over 7%, while high-yield savings accounts went from 0.5% to 5% nominal.

Inflation Expectations Drive Nominal Rate Movements

Financial markets price nominal rates based on inflation expectations, not just current inflation. The nominal rate on a 10-year Treasury bond reflects:

- Expected average inflation over the next decade

- A real return premium (typically 1-2%)

- Risk premiums for uncertainty

Example: If markets expect 2.5% average inflation over 10 years and demand a 2% real return, the nominal 10-year Treasury yield will approximate 4.5%.

When inflation expectations rise suddenly, nominal rates spike across all maturities. The 2021-2022 inflation surge pushed nominal Treasury yields from 1.5% to over 4% as markets repriced inflation expectations from 2% to 3-4%.

The Yield Curve and Nominal Rate Structure

The yield curve plots nominal interest rates against maturity lengths. Under normal conditions:

- Short-term nominal rates (3-month T-bills): 3-4%

- Medium-term nominal rates (5-year notes): 4-5%

- Long-term nominal rates (30-year bonds): 5-6%

This upward slope compensates investors for inflation uncertainty over longer periods. When the curve inverts (short-term nominal rates exceed long-term rates), it often signals recession expectations—markets anticipate the Fed will cut rates in the future, reducing long-term nominal yields.

Understanding yield curve dynamics helps investors position portfolios appropriately. A steep curve favors long-term bonds; a flat or inverted curve favors short-term instruments or stocks.

Calculating Nominal Interest Rate: Step-by-Step Examples

Example 1: Finding Nominal Rate from Real Rate and Inflation

Scenario: You want to earn a 5% real return on a loan. You expect 3.2% inflation over the loan period. What nominal rate should you charge?

Step 1: Identify variables

- r = 0.05 (desired real rate)

- π = 0.032 (expected inflation)

- i = ? (nominal rate to find)

Step 2: Apply the Fisher equation

i = [(1 + r) × (1 + π)] – 1

Step 3: Substitute values

i = [(1 + 0.05) × (1 + 0.032)] – 1

i = [1.05 × 1.032] – 1

i = 1.0836 – 1

Step 4: Calculate the result

i = 0.0836 or 8.36%

Answer: Charge a nominal interest rate of 8.36% to achieve a 5% real return with 3.2% expected inflation.

Verification using approximation:

i ≈ r + π = 0.05 + 0.032 = 0.082 or 8.2%

The precise answer (8.36%) exceeds the approximation (8.2%) by 0.16 percentage points, demonstrating why the full formula matters for accurate calculations.

Example 2: Converting Nominal Rate to Real Rate

Scenario: A bond pays 6.8% nominal interest. Inflation is currently 2.9%. What real return are you earning?

Step 1: Identify variables

- i = 0.068 (nominal rate)

- π = 0.029 (inflation rate)

- r = ? (real rate to find)

Step 2: Apply the rearranged Fisher equation

r = [(1 + i) / (1 + π)] – 1

Step 3: Substitute values

r = [(1 + 0.068) / (1 + 0.029)] – 1

r = [1.068 / 1.029] – 1

r = 1.0379 – 1

Step 4: Calculate the result

r = 0.0379 or 3.79%

Answer: Your real return is 3.79%, meaning your purchasing power increases by 3.79% annually.

Example 3: Finding Nominal APR from Monthly Payments

Scenario: You borrow $15,000 and repay $350 monthly for 48 months. What’s the nominal APR?

This requires solving for the interest rate in the loan payment formula:

PMT = P × [i(1 + i)^n] / [(1 + i)^n – 1]

Where:

- PMT = $350 (monthly payment)

- P = $15,000 (principal)

- n = 48 (number of payments)

- i = monthly interest rate (unknown)

Step 1: This equation requires iterative solving or a financial calculator

Using a financial calculator or spreadsheet RATE function:

- N = 48

- PV = -15000

- PMT = 350

- FV = 0

- Compute I/Y = 0.833% per month

Step 2: Convert the monthly rate to the nominal APR

Nominal APR = 0.00833 × 12 = 0.10 or 10%

Step 3: Calculate the effective annual rate for comparison

EAR = (1.00833)^12 – 1 = 0.1043 or 10.43%

Answer: The nominal APR is 10%, but the effective annual rate is 10.43% due to monthly compounding.

Example 4: Simple Interest Nominal Rate

Scenario: You invest $8,000 and receive $1,200 in simple interest after 3 years. What’s the nominal annual rate?

Step 1: Apply the simple interest nominal rate formula

R = I / (P × T)

Step 2: Substitute values

- I = $1,200 (interest earned)

- P = $8,000 (principal)

- T = 3 (years)

R = $1,200 / ($8,000 × 3)

R = $1,200 / $24,000

Step 3: Calculate the result

R = 0.05 or 5% per year

Answer: The nominal interest rate is 5% annually under simple interest.

Note: This same investment with compound interest at 5% nominal would have earned $1,261 instead of $1,200, demonstrating the power of compounding over simple interest.

Interactive HTML Element

💰 Nominal Interest Rate Calculator

Calculate nominal rates using different methods

Approximation: i ≈ r + π

Where R = nominal rate, I = interest, P = principal, T = time

Effective Annual Rate = (1 + i/n)^n – 1

Where i = periodic rate, n = periods per year

Conclusion: Mastering Nominal Interest Rate for Better Financial Decisions

The nominal interest rate forms the foundation of nearly every financial transaction you'll encounter—from the mortgage that finances your home to the savings account that holds your emergency fund. Understanding this concept moves you from passive consumer to informed decision-maker.

The key insights to remember:

The nominal rate is merely the starting point for analysis, not the conclusion. Always adjust for inflation to determine real returns and account for compounding to find effective rates. These adjustments reveal the true cost of borrowing and the actual growth of investments.

The Fisher equation—i = [(1 + r) × (1 + π)] - 1—provides the mathematical framework connecting nominal rates, real returns, and inflation. This formula explains why 5% nominal returns during 6% inflation destroy wealth while 5% nominal returns during 2% inflation build it.

Different compounding frequencies create gaps between nominal and effective rates. A 12% nominal APR becomes 12.68% with monthly compounding or 12.75% with daily compounding. These differences accumulate to thousands of dollars over typical loan or investment periods.

Actionable next steps:

- Review your current financial products and calculate their real returns after inflation using the formulas in this guide

- Compare effective rates, not nominal rates, when shopping for loans, credit cards, or investment accounts

- Build an investment strategy that targets real returns above inflation rather than chasing high nominal figures

- Understand the economic environment by monitoring Federal Reserve policy and inflation trends that drive nominal rate movements

- Use the interactive calculator above to run scenarios with your specific numbers before making borrowing or investing decisions

The math behind money rewards those who look beyond surface-level nominal rates to understand the deeper mechanics of real returns, compounding effects, and inflation adjustments. This knowledge transforms financial literacy from abstract concepts into concrete wealth-building advantages.

Every percentage point matters when compounded over decades. Every inflation adjustment reveals whether you're genuinely building wealth or merely maintaining purchasing power. Every comparison between nominal and effective rates prevents costly mistakes that drain thousands from your financial future.

Master these principles, apply them consistently, and watch as seemingly small advantages compound into substantial wealth over time. That's the power of understanding nominal interest rates—not just knowing the definition, but applying the math that separates financial success from financial mediocrity.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, where he teaches the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and financial independence. With a background in financial analysis and a passion for data-driven education, Max breaks down complex financial concepts into clear, actionable insights. His work focuses on helping beginners understand the cause-and-effect relationships that drive investment returns, risk management, and long-term wealth accumulation.

Educational Disclaimer

This article provides educational information about nominal interest rates and should not be construed as financial advice. Interest rate calculations involve assumptions about inflation, compounding, and economic conditions that may not match your specific situation. Actual returns and costs depend on individual circumstances, market conditions, and the specific terms of financial products.

Before making borrowing or investment decisions, consult with qualified financial professionals who can assess your personal financial situation, risk tolerance, and goals. Past performance of interest rates does not guarantee future results. The formulas and examples presented illustrate mathematical principles but cannot account for all variables affecting real-world financial outcomes.

The Rich Guy Math does not provide personalized financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. All content is for informational and educational purposes only.

Soruces

[1] Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), "Interest Rates, Discount Rate for United States," Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2025.

[2] Fisher, Irving, "The Theory of Interest," Macmillan, 1930.

[3] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, "What is the difference between a mortgage interest rate and an APR?" CFPB.gov, 2025.

[4] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Policy Tools," FederalReserve.gov, 2025.

[5] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Consumer Price Index," BLS.gov, 2025.

[6] Investopedia, "Nominal Interest Rate," Investopedia.com, 2025.

[7] CFA Institute, "Fixed Income Analysis," CFA Program Curriculum, 2025.

Frequently Asked Questions About Nominal Interest Rate

What is the difference between nominal and real interest rate?

The nominal interest rate is the stated percentage on a loan or investment without adjusting for inflation. The real interest rate adjusts the nominal rate for inflation's impact on purchasing power. Use the formula r = [(1 + i) / (1 + π)] - 1, where i is the nominal rate and π is inflation. For example, a 7% nominal rate with 3% inflation yields roughly a 4% real return.

How do you calculate nominal interest rate?

Use the Fisher equation: i = [(1 + r) × (1 + π)] - 1, where r is real return and π is expected inflation. For simple interest, use R = I / (P × T), where I is interest earned, P is principal, and T is years. For periodic interest, multiply the periodic rate by the number of periods per year: Nominal APR = periodic rate × periods per year.

Is APR the same as nominal interest rate?

Yes. APR (Annual Percentage Rate) represents the nominal interest rate expressed annually and does not include intra-year compounding. APY, on the other hand, includes compounding and reflects the true effective annual rate.

Why is nominal interest rate higher than real interest rate?

Nominal rates exceed real rates during positive inflation because lenders require compensation for both real returns and inflation. Nominal rate = real rate + inflation premium. In rare cases of deflation, nominal rates may fall below real rates.

Can nominal interest rate be negative?

Yes. Some European and Japanese central banks used negative nominal rates in the 2010s to stimulate economic activity. In these cases, depositors effectively pay banks to hold funds. Negative real rates are more common when inflation exceeds nominal rates.

How does compounding affect nominal interest rate?

Compounding does not change the nominal interest rate itself, but it increases the effective annual rate (EAR). For example, a 12% nominal rate compounded monthly produces a 12.68% effective return. More frequent compounding widens the gap between nominal and effective rates.

What nominal interest rate should I expect in 2025?

In 2025, nominal interest rates vary by product: high-yield savings (4–5%), mortgages (6–8%), and credit cards (15–25%). Rates reflect Federal Reserve policy and inflation trends. Individual rates depend on credit profile and loan terms. Always compare both nominal and effective rates.