When a business generates $1 million in revenue but spends $900,000 to earn it, something fundamental reveals itself in the math behind money. The company isn’t just less profitable; it’s operationally inefficient. Efficiency ratios expose this critical relationship between what a company spends and what it earns, providing investors and business owners with a mathematical lens to evaluate operational performance.

Understanding efficiency ratios transforms how investors analyze companies. These metrics answer a deceptively simple question: How much does a business spend to generate each dollar of revenue? The answer determines whether management allocates resources wisely or wastes capital on bloated operations. For anyone building wealth through evidence-based investing, efficiency ratios provide essential data-driven insights into which companies convert inputs into outputs most effectively.

This comprehensive guide explains efficiency ratios from first principles, demonstrating the formulas, interpretations, and real-world applications that separate efficient operators from capital destroyers.

Key Takeaways

Efficiency ratios measure how effectively a company uses its resources to generate revenue, with lower percentages generally indicating better operational performance

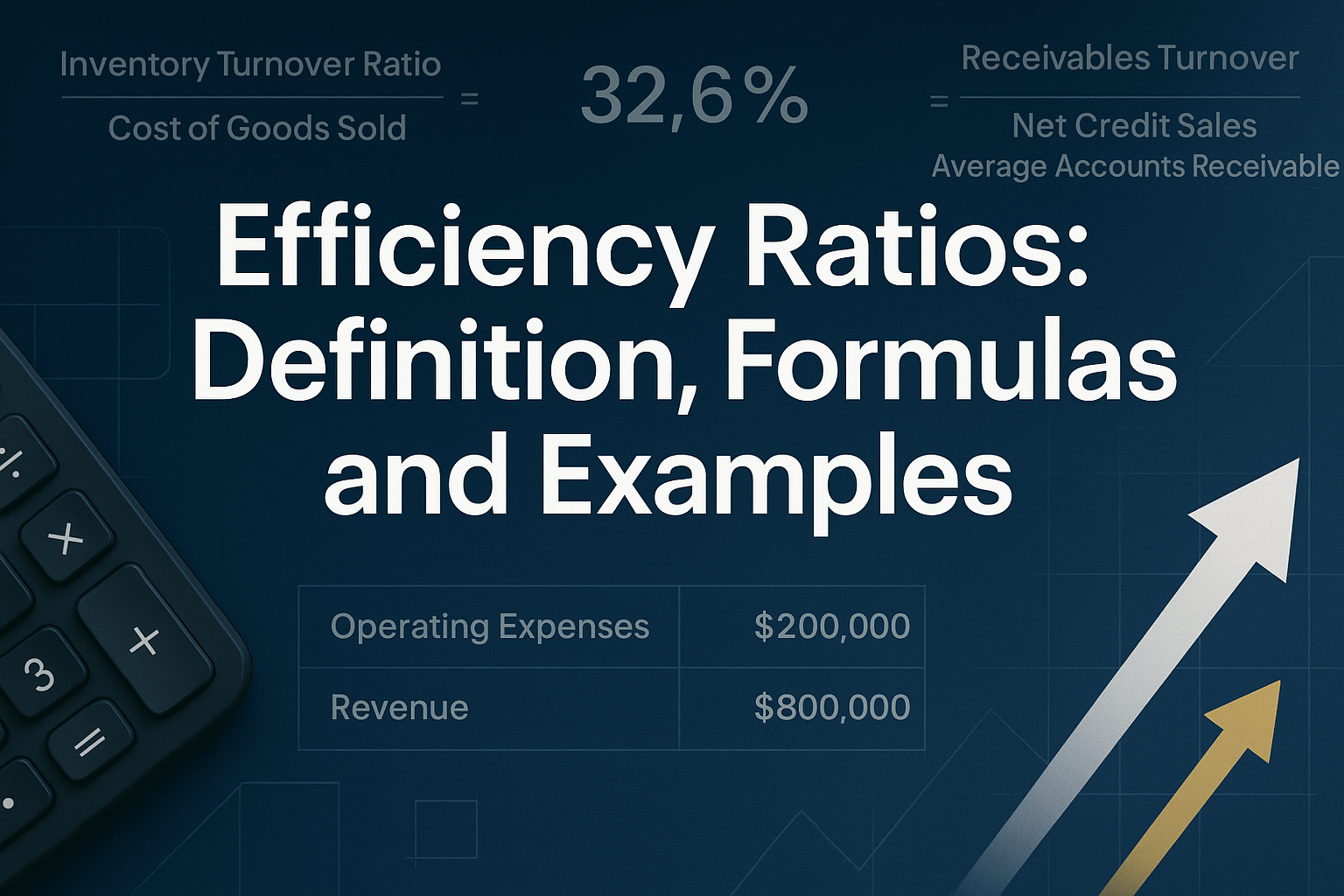

The basic efficiency ratio formula (Operating Expenses ÷ Net Operating Income × 100) reveals what percentage of revenue goes toward overhead costs rather than profit

Different industries require different efficiency benchmarks; a 50% efficiency ratio signals excellence in banking, but might indicate problems in retail

Multiple efficiency ratios exist for specific purposes, including asset turnover, inventory turnover, and receivables turnover, each measuring different operational aspects

Tracking efficiency ratios over time reveals management effectiveness and whether a company is improving or deteriorating in operational discipline

What Are Efficiency Ratios? Understanding the Fundamentals

Efficiency ratios are financial metrics that quantify how well a company converts resources into revenue. These ratios belong to the broader category of activity ratios, which measure the relationship between operational inputs (expenses, assets, and inventory) and outputs (sales, revenue, and income).

At their core, efficiency ratios answer a fundamental question about business operations: For every dollar a company invests in running its business, how many dollars of revenue does it generate?

The Basic Efficiency Ratio Formula

The most commonly referenced efficiency ratio uses this formula:

Efficiency Ratio = (Operating Expenses ÷ Net Operating Income) × 100

Where:

- Operating Expenses = costs required to run the business (salaries, rent, utilities, marketing)

- Net Operating Income = revenue minus cost of goods sold (COGS)

The result expresses the percentage of operating income that is consumed by overhead expenses. A company with an efficiency ratio of 60% spends $0.60 in operating expenses for every dollar of operating income it generates.

Lower percentages indicate superior efficiency because the company spends less to generate the same revenue. A firm that reduces its efficiency ratio from 70% to 55% has fundamentally improved its operational performance; it now keeps more of each revenue dollar as potential profit.

Why Efficiency Ratios Matter for Investors

Efficiency ratios reveal operational discipline that doesn’t always appear in headline metrics like revenue growth or earnings per share. Two companies might report identical revenue, but vastly different efficiency ratios expose which management team runs a tighter operation.

Consider this scenario:

| Company | Revenue | Operating Expenses | Efficiency Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company A | $10M | $6M | 60% |

| Company B | $10M | $4M | 40% |

Both companies generate $10 million in revenue, but Company B operates far more efficiently. It spends $2 million less to generate the same revenue, meaning those savings flow directly to profitability. Over time, more efficient operators compound advantages through better capital allocation strategies and stronger competitive positioning.

Efficiency ratios also function as early warning systems. When a company’s efficiency ratio deteriorates quarter after quarter, it signals an operational problem such as bloating headcount, rising costs, or declining pricing power. These trends often precede earnings disappointments and stock price declines.

Insight: Efficiency ratios measure operational execution, not just financial results. A company can grow revenue while simultaneously destroying value if efficiency deteriorates faster than sales increase.

Industry-Specific Applications

Different industries apply efficiency ratios differently because business models vary dramatically in their cost structures and asset requirements.

Banking and Financial Services use a specialized efficiency ratio:

Bank Efficiency Ratio = (Non-Interest Expenses ÷ Revenue) × 100

Banks don’t have traditional “operating expenses” in the same way as manufacturers. Instead, they incur non-interest expenses (employee salaries, technology infrastructure, branch operations) while generating revenue from both interest income and fees. A bank efficiency ratio below 50% generally indicates strong operational performance, while ratios above 60% suggest bloated operations.

Retail and Manufacturing focus more heavily on asset-based efficiency ratios like inventory turnover and asset turnover, which measure how effectively companies deploy physical resources rather than just controlling expenses.

Technology and Service Companies often emphasize operating efficiency ratios because they operate with minimal physical assets but significant labor and infrastructure costs.

Understanding these industry-specific applications prevents misinterpretation. A 35% efficiency ratio might signal exceptional performance for a regional bank, but could indicate serious problems for a software company with different cost structures.

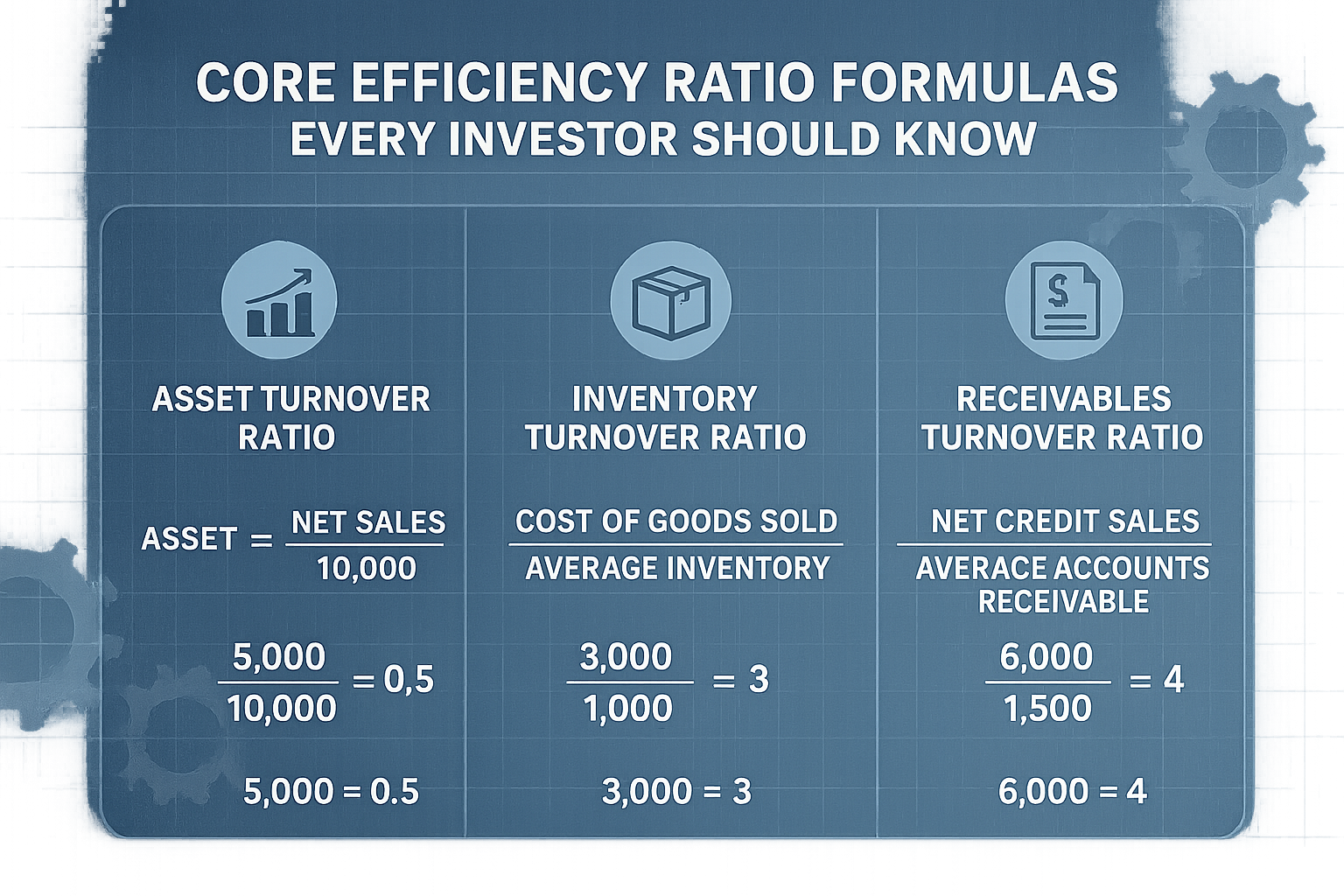

Core Efficiency Ratio Formulas Every Investor Should Know

Multiple efficiency ratio formulas exist, each measuring different aspects of operational performance. Mastering these formulas provides a comprehensive view of how effectively a company uses its resources.

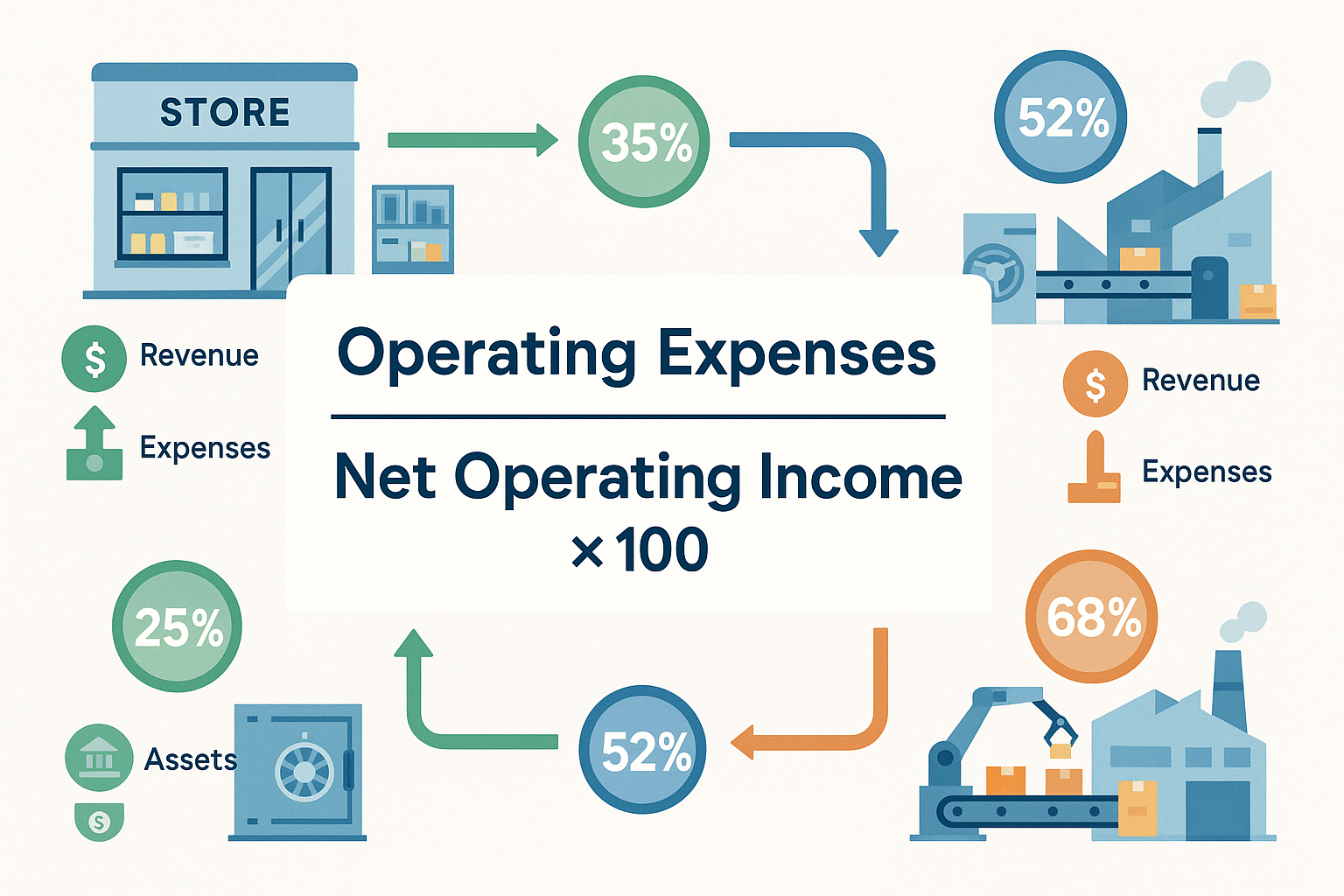

1. Operating Efficiency Ratio

The operating efficiency ratio measures total operating costs relative to revenue:

Operating Efficiency Ratio = (Operating Expenses + Cost of Goods Sold) ÷ Net Sales

This formula captures both direct costs (COGS) and indirect costs (operating expenses) as a percentage of total revenue. The result shows what portion of each sales dollar gets consumed by costs before reaching operating profit.

Example:

- Net Sales: $5,000,000

- Cost of Goods Sold: $2,000,000

- Operating Expenses: $1,500,000

Operating Efficiency Ratio = ($1,500,000 + $2,000,000) ÷ $5,000,000 = 0.70 or 70%

This company spends $0.70 of every revenue dollar on costs, leaving $0.30 for operating profit, interest, taxes, and net income. Improving this ratio to 65% would increase operating margin by 5 percentage points—a significant profitability improvement.

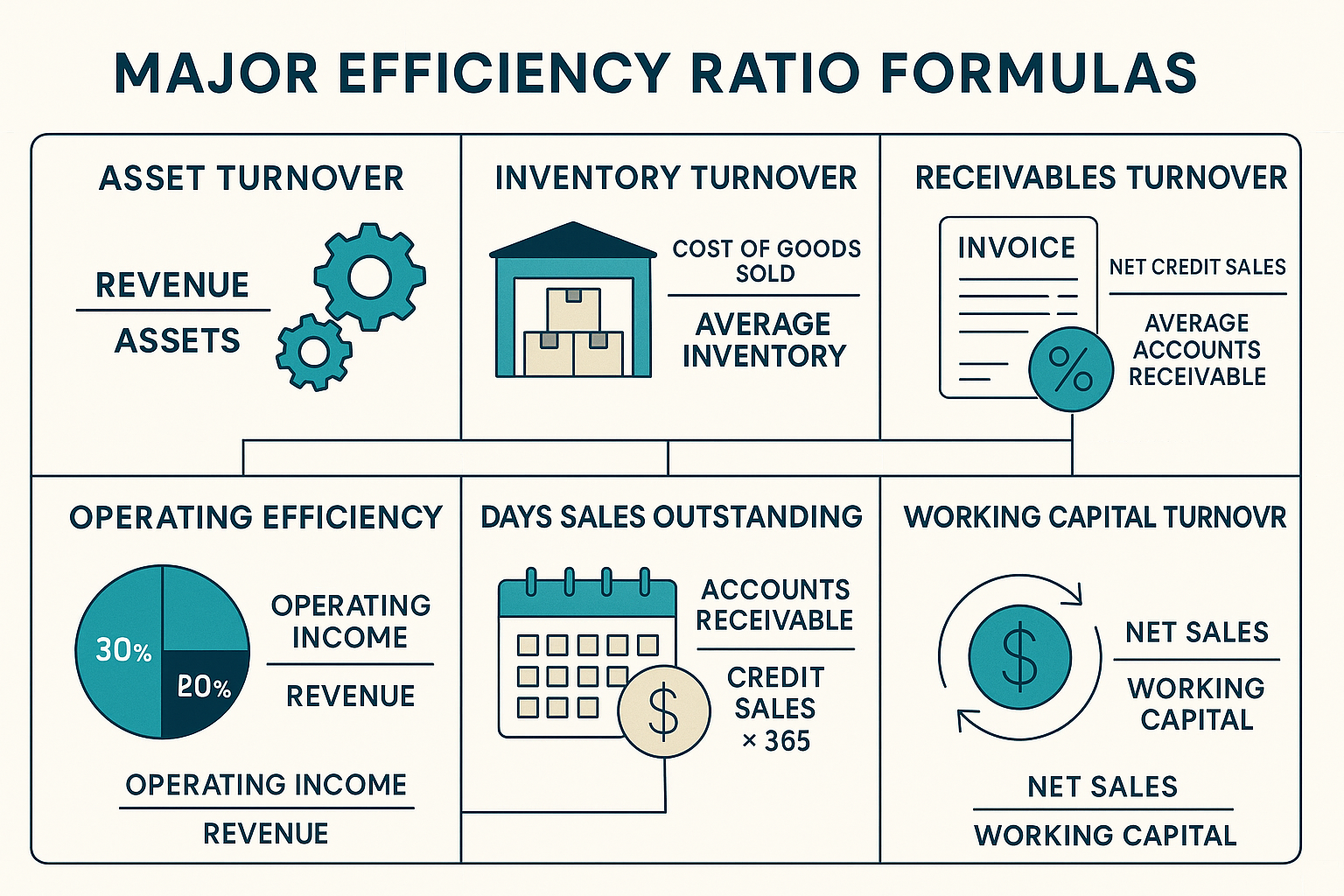

2. Asset Turnover Ratio

The asset turnover ratio measures how efficiently a company uses its total assets to generate revenue:

Asset Turnover Ratio = Net Sales ÷ Average Total Assets

This ratio doesn’t express a percentage; instead, it shows how many dollars of revenue the company generates per dollar of assets employed. Higher numbers indicate more efficient asset utilization.

Example:

- Net Sales: $8,000,000

- Average Total Assets: $4,000,000

Asset Turnover Ratio = $8,000,000 ÷ $4,000,000 = 2.0

This company generates $2 in revenue for every $1 in assets. A ratio of 2.0 might be excellent for a grocery retailer but poor for a capital-intensive manufacturer. Context matters enormously when interpreting asset turnover.

Companies can improve asset turnover by either increasing sales (numerator) or reducing assets (denominator). Selling underutilized equipment, reducing excess inventory, or improving accounts receivable collection all boost this metric.

3. Inventory Turnover Ratio

The inventory turnover ratio measures how many times per year a company sells and replaces its inventory:

Inventory Turnover Ratio = Cost of Goods Sold ÷ Average Inventory

Higher turnover indicates faster inventory movement, which reduces storage costs, minimizes obsolescence risk, and improves cash flow. Slower turnover suggests excess inventory, poor sales, or inefficient purchasing.

Example:

- Cost of Goods Sold: $6,000,000

- Average Inventory: $500,000

Inventory Turnover Ratio = $6,000,000 ÷ $500,000 = 12

This company turns over its inventory 12 times annually, or roughly once per month. For a grocery store, this might be slow. For a furniture retailer, it could be exceptional. Industry benchmarks provide essential context.

Investors can convert inventory turnover into days inventory outstanding (DIO) using this formula:

Days Inventory Outstanding = 365 ÷ Inventory Turnover Ratio

Using the example above: 365 ÷ 12 = 30.4 days

The company holds inventory for approximately 30 days before selling it. Shorter periods generally indicate better efficiency and stronger demand for products.

4. Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

The accounts receivable turnover ratio measures how efficiently a company collects payments from customers:

Accounts Receivable Turnover = Net Credit Sales ÷ Average Accounts Receivable

This ratio shows how many times per year a company collects its average receivables balance. Higher numbers indicate faster collection and better credit management.

Example:

- Net Credit Sales: $3,000,000

- Average Accounts Receivable: $250,000

Accounts Receivable Turnover = $3,000,000 ÷ $250,000 = 12

The company collects its receivables 12 times annually. Like inventory turnover, this converts to a time period:

Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) = 365 ÷ Receivables Turnover

DSO = 365 ÷ 12 = 30.4 days

The company takes approximately 30 days to collect payment after making a sale. Comparing this to payment terms reveals efficiency. If the company offers “net 30” terms, collections align with policy. If terms are “net 15,” the 30-day collection period indicates problems with credit management or customer payment behavior.

Deteriorating receivables turnover often signals customer financial stress, poor credit policies, or revenue quality issues. Companies sometimes inflate revenue by booking sales to customers unlikely to pay, temporarily boosting revenue while accounts receivable balloons, a red flag for investors.

5. Working Capital Turnover

The working capital turnover ratio measures how effectively a company uses working capital to generate sales:

Working Capital Turnover = Net Sales ÷ Average Working Capital

Where Working Capital = Current Assets – Current Liabilities

This ratio shows how many dollars of revenue the company generates per dollar of working capital employed in operations.

Example:

- Net Sales: $10,000,000

- Average Working Capital: $2,000,000

Working Capital Turnover = $10,000,000 ÷ $2,000,000 = 5

The company generates $5 in sales for every $1 of working capital. Higher ratios indicate more efficient use of short-term resources, though excessively high ratios might signal insufficient working capital to support growth.

Understanding the cash conversion cycle provides additional context for working capital efficiency, revealing how quickly a company converts inventory and receivables into cash.

6. Fixed Asset Turnover

The fixed asset turnover ratio isolates how efficiently a company uses long-term assets like property, plant, and equipment:

Fixed Asset Turnover = Net Sales ÷ Average Net Fixed Assets

This metric particularly matters for capital-intensive industries like manufacturing, utilities, and telecommunications, where fixed assets represent the majority of total assets.

Example:

- Net Sales: $15,000,000

- Average Net Fixed Assets: $5,000,000

Fixed Asset Turnover = $15,000,000 ÷ $5,000,000 = 3

The company generates $3 in revenue for every $1 invested in fixed assets. Declining fixed asset turnover might indicate excess capacity, aging equipment, or poor capital investment decisions.

Takeaway: Each efficiency ratio illuminates a different aspect of operational performance. Analyzing multiple ratios simultaneously provides a comprehensive picture of how effectively management deploys resources across the business.

How to Calculate and Interpret Efficiency Ratios: Step-by-Step Examples

Understanding formulas matters less than knowing how to apply them to real financial statements and interpret the results. This section demonstrates practical calculation and analysis using realistic scenarios.

Step 1: Gather the Required Financial Data

Efficiency ratio calculations require data from two primary financial statements:

Income Statement provides:

- Net Sales / Revenue

- Cost of Goods Sold

- Operating Expenses

- Net Operating Income

Balance Sheet provides:

- Total Assets

- Current Assets

- Fixed Assets

- Inventory

- Accounts Receivable

- Current Liabilities

For ratios requiring averages (asset turnover, inventory turnover, receivables turnover), calculate the average of beginning and ending period balances:

Average = (Beginning Balance + Ending Balance) ÷ 2

This approach smooths out seasonal fluctuations and provides more accurate efficiency measurements.

Step 2: Calculate the Efficiency Ratio

Let’s work through a comprehensive example using a hypothetical retail company’s annual financial data:

ABC Retail Company – Annual Financial Data:

Income Statement:

- Net Sales: $12,000,000

- Cost of Goods Sold: $7,200,000

- Gross Profit: $4,800,000

- Operating Expenses: $2,400,000

- Operating Income: $2,400,000

Balance Sheet:

- Total Assets (Beginning): $8,000,000

- Total Assets (Ending): $10,000,000

- Inventory (Beginning): $1,200,000

- Inventory (Ending): $1,800,000

- Accounts Receivable (Beginning): $800,000

- Accounts Receivable (Ending): $1,200,000

Calculating Operating Efficiency Ratio:

Operating Efficiency = (Operating Expenses + COGS) ÷ Net Sales

= ($2,400,000 + $7,200,000) ÷ $12,000,000

= $9,600,000 ÷ $12,000,000

= 0.80 or 80%

ABC Retail spends $0.80 of every sales dollar on costs, leaving $0.20 for operating profit.

Calculating Asset Turnover:

Average Total Assets = ($8,000,000 + $10,000,000) ÷ 2 = $9,000,000

Asset Turnover = Net Sales ÷ Average Total Assets

= $12,000,000 ÷ $9,000,000

= 1.33

ABC Retail generates $1.33 in revenue for every $1 in assets.

Calculating Inventory Turnover:

Average Inventory = ($1,200,000 + $1,800,000) ÷ 2 = $1,500,000

Inventory Turnover = COGS ÷ Average Inventory

= $7,200,000 ÷ $1,500,000

= 4.8

ABC Retail turns over its inventory 4.8 times annually.

Days Inventory Outstanding = 365 ÷ 4.8 = 76 days

Calculating Receivables Turnover:

Average Accounts Receivable = ($800,000 + $1,200,000) ÷ 2 = $1,000,000

Receivables Turnover = Net Sales ÷ Average Accounts Receivable

= $12,000,000 ÷ $1,000,000

= 12

Days Sales Outstanding = 365 ÷ 12 = 30.4 days

Step 3: Interpret the Results with Industry Context

Raw numbers mean little without comparative context. Efficiency ratios gain meaning through three types of comparison:

1. Industry Benchmarks

Different industries operate with fundamentally different efficiency profiles:

| Industry | Typical Asset Turnover | Typical Inventory Turnover |

|---|---|---|

| Grocery Retail | 2.5 – 3.5 | 10 – 15 |

| Apparel Retail | 1.5 – 2.5 | 4 – 6 |

| Auto Manufacturing | 0.8 – 1.2 | 8 – 12 |

| Software/SaaS | 0.4 – 0.8 | N/A |

| Banking | 0.05 – 0.10 | N/A |

ABC Retail’s asset turnover of 1.33 and inventory turnover of 4.8 suggest it operates in apparel or general merchandise retail. These ratios would be poor for a grocery chain but reasonable for a clothing retailer.

2. Historical Trends

Comparing current ratios to the company’s historical performance reveals whether efficiency is improving or deteriorating:

| Year | Operating Efficiency | Asset Turnover | Inventory Turnover |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 78% | 1.45 | 5.2 |

| 2023 | 79% | 1.38 | 4.9 |

| 2024 | 80% | 1.33 | 4.8 |

This trend analysis reveals concerning deterioration across all efficiency metrics. Operating efficiency worsened (higher percentage), asset turnover declined, and inventory turnover slowed. These trends suggest ABC Retail faces operational challenges, perhaps increased competition, rising costs, or weakening demand.

3. Competitor Comparison

Comparing ABC Retail to direct competitors isolates company-specific performance from industry-wide trends:

| Company | Operating Efficiency | Asset Turnover | Inventory Turnover |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABC Retail | 80% | 1.33 | 4.8 |

| Competitor X | 76% | 1.52 | 5.5 |

| Competitor Y | 82% | 1.28 | 4.3 |

| Industry Average | 79% | 1.38 | 4.9 |

ABC Retail performs slightly below the industry average on operating efficiency and asset turnover, suggesting room for improvement. However, it outperforms Competitor Y while trailing Competitor X.

Step 4: Identify Root Causes and Implications

Efficiency ratios diagnose problems but don’t explain causes. Declining inventory turnover could result from:

- Weakening demand for products

- Poor inventory management and excess stock

- Seasonal factors were not properly accounted for

- Deliberate inventory buildup ahead of expected demand

Investigating the underlying drivers requires examining additional metrics, management commentary, and business context. For investors, deteriorating efficiency ratios trigger deeper due diligence into operational performance.

Insight: Efficiency ratios function as diagnostic tools, not final verdicts. They reveal where to look for problems, but understanding why efficiency changed requires examining business operations, competitive dynamics, and management decisions.

Companies can improve efficiency ratios through multiple operational levers:

- Reducing operating expenses through automation, process improvements, or cost discipline

- Improving asset utilization by selling underperforming assets or increasing capacity utilization

- Accelerating inventory turnover through better demand forecasting and inventory management

- Speeding collections through improved credit policies and receivables management

Understanding these levers helps investors evaluate whether management teams are taking appropriate actions to address efficiency problems. A company acknowledging efficiency deterioration and implementing specific improvement initiatives demonstrates operational awareness. A company ignoring declining efficiency while management compensation increases signals potential governance problems.

For those building wealth through evidence-based investing, efficiency ratios provide quantitative evidence of operational quality that complements other valuation metrics like EBITDA and economic profit.

Industry-Specific Efficiency Benchmarks and What They Mean

Efficiency ratios vary dramatically across industries because different business models require different resource allocations. Understanding these industry-specific benchmarks prevents misinterpretation and enables meaningful comparisons.

Banking and Financial Services

Banks and financial institutions use a specialized efficiency ratio formula:

Bank Efficiency Ratio = Non-Interest Expenses ÷ (Net Interest Income + Non-Interest Income)

This ratio measures what percentage of revenue gets consumed by operating expenses. Unlike operating companies, banks generate revenue primarily through net interest margin (the spread between lending and borrowing rates) and fees.

Industry Benchmarks:

- Below 50%: Excellent efficiency, indicating tight cost control and strong operational leverage

- 50-60%: Good efficiency, typical for well-managed regional and national banks

- 60-70%: Average efficiency, suggesting room for improvement

- Above 70%: Poor efficiency, indicating bloated operations or revenue challenges

Major U.S. banks typically report efficiency ratios between 55-65%. Community banks often run higher (65-75%) due to smaller scale and higher relative overhead costs.

Example: Regional Bank Analysis

First National Bank reports:

- Net Interest Income: $450 million

- Non-Interest Income: $150 million

- Non-Interest Expenses: $330 million

Bank Efficiency Ratio = $330M ÷ ($450M + $150M) = $330M ÷ $600M = 55%

This 55% ratio indicates solid efficiency for a regional bank. The institution spends $0.55 to generate each dollar of revenue, leaving $0.45 for provisions, taxes, and net income.

If the bank reduces non-interest expenses to $300 million while maintaining revenue, the efficiency ratio improves to 50%, a significant operational achievement that flows directly to profitability.

Retail Industry

Retail companies focus heavily on asset turnover and inventory turnover because physical inventory and store assets represent major capital investments.

Retail Efficiency Benchmarks:

| Retail Segment | Asset Turnover | Inventory Turnover | Operating Margin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grocery/Supermarket | 2.5 – 3.5 | 10 – 15 | 1 – 3% |

| Discount Retail | 2.0 – 3.0 | 6 – 10 | 3 – 5% |

| Apparel | 1.5 – 2.5 | 4 – 6 | 5 – 10% |

| Luxury Goods | 0.8 – 1.5 | 2 – 4 | 10 – 20% |

| E-commerce | 1.5 – 2.5 | 8 – 12 | 2 – 8% |

Grocery retailers operate on razor-thin margins but compensate through extremely high inventory turnover—selling products quickly and reinvesting cash. Luxury retailers accept slower turnover because higher margins offset the carrying costs of premium inventory.

Example: Comparing Retail Models

Discount Retailer A:

- Asset Turnover: 2.8

- Inventory Turnover: 9

- Operating Margin: 4%

Luxury Retailer B:

- Asset Turnover: 1.2

- Inventory Turnover: 3

- Operating Margin: 18%

Retailer A generates more revenue per dollar of assets and turns inventory faster, but Retailer B earns far higher margins on each sale. Neither model is inherently superior—they represent different strategic approaches to retail profitability.

Investors should compare retailers within the same segment rather than across segments. Comparing a discount retailer to a luxury brand produces meaningless conclusions because their business models operate on fundamentally different economic principles.

Manufacturing Industry

Manufacturing companies typically show lower asset turnover than retailers because factories, equipment, and machinery require substantial capital investment. However, manufacturers often achieve higher operating margins that justify the capital intensity.

Manufacturing Efficiency Benchmarks:

| Manufacturing Type | Asset Turnover | Inventory Turnover | Operating Margin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auto Manufacturing | 0.8 – 1.2 | 8 – 12 | 5 – 10% |

| Industrial Equipment | 0.6 – 1.0 | 4 – 6 | 8 – 15% |

| Consumer Electronics | 1.0 – 1.5 | 6 – 10 | 5 – 12% |

| Food Processing | 1.2 – 1.8 | 8 – 15 | 6 – 12% |

Manufacturing efficiency depends heavily on capacity utilization. A factory operating at 90% capacity shows dramatically better asset turnover than the same facility at 60% capacity. Economic cycles significantly impact manufacturing efficiency ratios as demand fluctuates.

Fixed asset turnover becomes particularly important for manufacturers:

Fixed Asset Turnover = Net Sales ÷ Average Net Fixed Assets

A manufacturer with $500 million in sales and $200 million in net fixed assets achieves a fixed asset turnover of 2.5, generating $2.50 in revenue for every dollar invested in plant and equipment.

Declining fixed asset turnover often signals:

- Excess capacity from overinvestment

- Aging equipment reduces productivity

- Demand weakness relative to production capability

- Poor capital allocation decisions

Technology and Software

Technology companies, particularly software-as-a-service (SaaS) businesses, operate with minimal physical assets but significant human capital and infrastructure costs. Traditional asset-based efficiency ratios often appear misleading for these businesses.

Technology Efficiency Metrics:

Instead of conventional efficiency ratios, technology investors focus on:

- Rule of 40: Revenue Growth Rate + Profit Margin ≥ 40%

- Magic Number: New ARR ÷ Sales & Marketing Spend (measures customer acquisition efficiency)

- Operating Leverage: Revenue growth rate minus operating expense growth rate

A SaaS company growing revenue 30% annually while maintaining 15% operating margins achieves the Rule of 40 threshold (30% + 15% = 45%), demonstrating efficient growth.

Traditional efficiency ratios like asset turnover often exceed 5-10 for software companies because they generate substantial revenue with minimal physical assets. These high ratios don’t necessarily indicate superior efficiency; they simply reflect a fundamentally different business model.

Service Industries

Professional services, consulting, and other service businesses show efficiency patterns distinct from asset-heavy industries:

Service Industry Characteristics:

- Very high asset turnover (often 3-8) due to minimal physical assets

- Revenue per employee becomes the critical efficiency metric

- Operating margins typically range from 10-25% for professional services

- Utilization rates (billable hours ÷ total hours) measure human capital efficiency

A consulting firm generating $200,000 in revenue per employee demonstrates better efficiency than a competitor producing $150,000 per employee, assuming similar service offerings and margins.

Takeaway: Industry context determines whether an efficiency ratio signals strength or weakness. A 50% efficiency ratio indicates excellence for a bank, mediocrity for a software company, and potential problems for a retailer. Always compare companies within their industry peer group.

Understanding these industry-specific benchmarks enables investors to identify truly efficient operators within each sector. A regional bank consistently maintaining a 48% efficiency ratio while competitors average 58% possesses a significant competitive advantage. That operational excellence typically translates to superior returns on equity and stronger dividend growth over time.

Common Mistakes When Analyzing Efficiency Ratios

Even experienced investors make errors when interpreting efficiency ratios. Avoiding these common pitfalls improves analytical accuracy and investment decisions.

Mistake 1: Ignoring Industry Context

The Error: Comparing efficiency ratios across different industries and concluding that companies with higher ratios always perform better.

Why It’s Wrong: A software company with an asset turnover of 8 isn’t necessarily more efficient than a manufacturer with an asset turnover of 1.2. These businesses operate with completely different capital requirements and economic models.

The Solution: Always compare efficiency ratios to industry benchmarks and direct competitors. A retailer with an asset turnover of 2.2 might be highly efficient if competitors average 1.8, even though the absolute number appears low compared to other industries.

Mistake 2: Focusing on a Single Period

The Error: Evaluating efficiency based on one quarter or year without examining trends over time.

Why It’s Wrong: Efficiency ratios fluctuate due to seasonal factors, one-time events, accounting changes, and business cycles. A single period provides insufficient information to assess operational quality.

The Solution: Analyze efficiency ratios over at least 3-5 years to identify meaningful trends. A company showing consistent improvement in operating efficiency from 68% to 62% over three years demonstrates genuine operational progress. A company bouncing between 55% and 75% quarterly shows volatility that requires investigation.

Mistake 3: Overlooking Accounting Differences

The Error: Comparing companies without adjusting for different accounting policies, particularly regarding depreciation, inventory valuation, and revenue recognition.

Why It’s Wrong: Two identical companies using different depreciation methods (straight-line vs. accelerated) or inventory accounting (FIFO vs. LIFO) will report different efficiency ratios even with identical operations.

The Solution: Review accounting policies in financial statement footnotes. When comparing companies, adjust for material accounting differences or acknowledge these limitations in the analysis. Understanding depreciation methods and amortization vs depreciation helps identify these discrepancies.

Mistake 4: Assuming Lower Is Always Better

The Error: Believing that lower efficiency ratios always indicate superior performance without considering trade-offs.

Why It’s Wrong: A company can artificially improve its efficiency ratio by underinvesting in critical areas like research and development, employee training, or infrastructure maintenance. Short-term efficiency gains might create long-term competitive problems.

The Solution: Evaluate efficiency ratios alongside growth rates, market share trends, and competitive positioning. A company improving its efficiency ratio from 65% to 55% while losing market share and cutting R&D might be harvesting the business rather than building sustainable value.

Mistake 5: Ignoring Balance Sheet Quality

The Error: Analyzing efficiency ratios without examining the underlying balance sheet quality and working capital management.

Why It’s Wrong: A company can temporarily boost asset turnover by reducing inventory to dangerously low levels, creating stockout risks. Similarly, aggressive collection policies might improve receivables turnover while damaging customer relationships.

The Solution: Examine efficiency ratios in conjunction with absolute levels of inventory, receivables, and payables. Also, review the cash conversion cycle to understand how efficiently the company converts working capital into cash.

Mistake 6: Neglecting External Factors

The Error: Attributing all efficiency ratio changes to management decisions without considering external economic, regulatory, or competitive factors.

Why It’s Wrong: Efficiency ratios often deteriorate during economic downturns due to lower capacity utilization, not necessarily poor management. Similarly, new regulations might increase compliance costs and worsen efficiency ratios industry-wide.

The Solution: Consider macroeconomic conditions, industry trends, and regulatory changes when interpreting efficiency ratio movements. A company maintaining stable efficiency during a recession while competitors deteriorate demonstrates relative strength even if absolute ratios worsen.

Mistake 7: Overlooking Revenue Quality

The Error: Celebrating improving efficiency ratios without questioning whether revenue growth is sustainable and high-quality.

Why It’s Wrong: Companies sometimes boost efficiency metrics through aggressive revenue recognition, channel stuffing, or extending generous payment terms that inflate sales while creating future collection problems.

The Solution: Examine accounts receivable trends relative to revenue growth. If receivables grow faster than sales, it suggests customers are taking longer to pay, a warning sign about revenue quality. Review the cash flow statement to verify that revenue converts to actual cash.

Insight: Efficiency ratios provide valuable signals, but they require careful interpretation within proper context. The best analysts combine efficiency ratio analysis with broader financial statement analysis, competitive assessment, and business model understanding.

How to Use Efficiency Ratios to Make Better Investment Decisions

Understanding efficiency ratios academically matters less than knowing how to apply them in real investment analysis. This section demonstrates practical applications for stock selection, portfolio management, and risk assessment.

Application 1: Identifying Operational Excellence

Investors seeking quality companies should screen for consistently superior efficiency ratios within industry peer groups. Companies maintaining efficiency advantages over competitors often possess:

- Stronger competitive positions through cost advantages

- Better management teams that allocate capital wisely

- Sustainable profitability that supports dividend growth and share buybacks

- Operational moats that protect against competition

Practical Screening Approach:

- Identify the industry or sector of interest

- Gather efficiency ratio data for all major competitors

- Calculate industry median efficiency ratios

- Screen for companies in the top quartile (25%) for efficiency

- Verify that superior efficiency persists over multiple years

- Investigate what drives the efficiency advantage

A retailer consistently maintaining inventory turnover 20% above competitors likely possesses superior merchandising, demand forecasting, or supply chain management. These operational advantages often translate to higher returns on invested capital and better long-term stock performance.

Application 2: Detecting Deteriorating Business Quality

Declining efficiency ratios often precede earnings disappointments and stock price declines. Monitoring efficiency trends provides early warning signals for portfolio holdings.

Warning Signs to Watch:

- Operating efficiency worsening (increasing percentage) for three consecutive quarters

- Asset turnover is declining while revenue remains flat or grows slowly

- Inventory turnover is slowing, combined with rising inventory levels

- Receivables turnover is declining faster than sales growth

- Days’ sales outstanding increasing beyond normal payment terms

When efficiency ratios deteriorate, investigate the causes:

- Read recent earnings call transcripts for management commentary

- Examine competitor efficiency trends to determine if problems are company-specific or industry-wide

- Review capacity utilization and fixed cost leverage

- Assess whether the company faces new competitive pressures

If the investigation reveals company-specific problems without clear remediation plans, consider reducing the position size or exiting the investment entirely. Efficiency deterioration often signals the early stages of competitive decline.

Application 3: Evaluating Turnaround Candidates

Companies trading at depressed valuations sometimes offer attractive returns if management can improve operational efficiency. Efficiency ratio analysis helps evaluate turnaround potential.

Turnaround Assessment Framework:

- Identify the efficiency gap: Compare the company’s current ratios to historical performance and peer averages

- Quantify improvement potential: Calculate the profit impact if efficiency returns to historical or peer levels

- Assess management credibility: Evaluate whether new leadership has a track record of operational improvement

- Monitor progress: Track quarterly efficiency metrics to verify the turnaround is progressing

Example Turnaround Analysis:

Struggling Retailer Inc. currently shows:

- Operating Efficiency: 88% (vs. 78% historically, 80% peer average)

- Asset Turnover: 1.1 (vs. 1.6 historically, 1.5 peer average)

- Inventory Turnover: 3.5 (vs. 5.0 historically, 4.8 peer average)

If management successfully returns operating efficiency to 80%, the company would save $80 million annually on a $1 billion revenue base. This profit improvement could justify significant stock appreciation if the market recognizes the operational progress.

However, turnaround investing carries substantial risk. Many companies never recover lost efficiency, and deteriorating operations often reflect permanent competitive disadvantages rather than temporary problems.

Application 4: Comparing Investment Alternatives

When evaluating multiple investment opportunities within the same sector, efficiency ratios help differentiate superior operators from mediocre ones.

Comparative Analysis Example:

Two regional banks offer similar dividend yields and trade at comparable price-to-book ratios:

| Metric | Bank A | Bank B |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency Ratio | 52% | 61% |

| Asset Turnover | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| ROE | 14% | 10% |

| Dividend Yield | 3.5% | 3.6% |

Bank A’s superior efficiency ratio (52% vs. 61%) explains its higher return on equity. The 9 percentage point efficiency advantage means Bank A keeps $0.09 more of every revenue dollar, flowing through to profitability.

All else equal, Bank A represents the better investment despite a slightly lower dividend yield. Its operational efficiency provides a stronger foundation for sustainable dividend growth over time. Investors focused on dividend investing should prioritize companies with strong efficiency ratios that support reliable cash generation.

Application 5: Assessing Acquisition Integration

When a company acquires a competitor, efficiency ratio analysis helps evaluate integration success. Successful acquisitions typically improve combined efficiency through:

- Eliminating duplicate overhead costs

- Consolidating facilities and operations

- Improving purchasing power with suppliers

- Sharing best practices across the combined entity

Post-Acquisition Monitoring:

Track the acquiring company’s efficiency ratios quarterly after the acquisition closes:

- Quarters 1-2: Efficiency often temporarily worsens due to integration costs

- Quarters 3-4: Efficiency should begin improving as synergies materialize

- Year 2+: Combined efficiency should exceed pre-acquisition levels

If efficiency ratios fail to improve 12-18 months post-acquisition, it suggests integration problems, overpaid purchase price, or unrealistic synergy assumptions. This pattern often precedes goodwill impairment charges and management changes.

Application 6: Building Diversified Portfolios

Efficiency ratio analysis complements other investment criteria when constructing diversified portfolios. Consider including companies with:

- Consistent efficiency leaders in each sector for core portfolio holdings

- Improving the efficiency of companies for growth-oriented positions

- Cyclical efficiency patterns that align with economic cycle positioning

During economic expansions, companies with operating leverage (high fixed costs) show improving efficiency as revenue grows faster than expenses. During recessions, companies with variable cost structures and strong working capital management maintain better efficiency.

Understanding these patterns helps with tactical sector allocation and risk management across market cycles.

Takeaway: Efficiency ratios transform from abstract metrics into practical investment tools when systematically applied to stock selection, position monitoring, and portfolio construction. Companies that consistently convert resources into revenue more effectively than competitors typically deliver superior long-term returns.

For investors building wealth through evidence-based investing, efficiency ratios provide quantitative evidence of operational quality that complements valuation metrics and growth analysis.

Efficiency Ratios vs Other Financial Metrics: Understanding the Differences

Efficiency ratios form one component of comprehensive financial analysis. Understanding how they relate to and differ from other metrics prevents confusion and improves analytical accuracy.

Efficiency Ratios vs Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios measure how much profit a company generates relative to revenue, assets, or equity. Common profitability ratios include:

- Gross Margin: (Revenue – COGS) ÷ Revenue

- Operating Margin: Operating Income ÷ Revenue

- Net Margin: Net Income ÷ Revenue

- Return on Assets (ROA): Net Income ÷ Total Assets

- Return on Equity (ROE): Net Income ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

Key Difference: Profitability ratios measure the result of operations (profit), while efficiency ratios measure the process of operations (resource utilization).

A company can show strong profitability with poor efficiency if it operates in a high-margin industry. Conversely, a company might demonstrate excellent efficiency but low profitability due to intense price competition.

Example:

| Company | Operating Efficiency | Operating Margin | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tech Co. | 45% | 35% | Excellent efficiency AND profitability |

| Retail Co. | 92% | 8% | Poor efficiency, modest profitability |

| Grocery Co. | 97% | 3% | Poor efficiency, low profitability |

Tech Co. demonstrates both operational efficiency and strong margins. Retail Co. operates inefficiently but maintains acceptable profitability through pricing power. Grocery Co. shows both poor efficiency and low margins, a concerning combination.

Investors should analyze efficiency and profitability together. Companies combining strong efficiency with high margins possess the most attractive operational profiles.

Efficiency Ratios vs Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet short-term obligations using current assets. Common liquidity ratios include:

- Current Ratio: Current Assets ÷ Current Liabilities

- Quick Ratio: (Current Assets – Inventory) ÷ Current Liabilities

- Cash Ratio: Cash ÷ Current Liabilities

Key Difference: Liquidity ratios measure financial safety and the ability to pay bills, while efficiency ratios measure operational effectiveness in using resources.

A company might show strong liquidity (current ratio of 2.5) but poor efficiency (declining inventory turnover). This combination suggests the company holds excess inventory and working capital, safe from a liquidity perspective but inefficient from an operational standpoint.

Efficiency Ratios vs Leverage Ratios

Leverage ratios measure how much debt a company uses to finance operations. Common leverage ratios include:

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio: Total Debt ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

- Debt Ratio: Total Debt ÷ Total Assets

- Interest Coverage: EBIT ÷ Interest Expense

Key Difference: Leverage ratios measure capital structure and financial risk, while efficiency ratios measure operational performance.

However, these metrics interact. Companies with superior operational efficiency can safely employ more leverage because consistent cash flow supports debt service. Companies with poor efficiency face greater financial risk from leverage because inconsistent operations threaten their ability to meet debt obligations.

Efficiency Ratios vs Valuation Ratios

Valuation ratios measure how the market prices a company relative to its financial metrics:

- Price-to-Earnings (P/E): Stock Price ÷ Earnings Per Share

- Price-to-Book (P/B): Stock Price ÷ Book Value Per Share

- Price-to-Sales (P/S): Market Cap ÷ Revenue

- Enterprise Value-to-EBITDA: Enterprise Value ÷ EBITDA

Key Difference: Valuation ratios measure market pricing, while efficiency ratios measure operational quality.

Companies with superior efficiency often trade at premium valuations because investors recognize that operational excellence supports sustainable profitability. A retailer with best-in-class inventory turnover might trade at 18x earnings while less efficient competitors trade at 12x earnings; the market pays a premium for operational quality.

The Integrated Analysis Approach

Sophisticated investors analyze companies using all ratio categories simultaneously:

- Efficiency ratios reveal operational quality

- Profitability ratios show the financial results of operations

- Liquidity ratios indicate short-term financial safety

- Leverage ratios expose financial risk from debt

- Valuation ratios determine if the market price offers value

Example Integrated Analysis:

Company XYZ shows:

- Operating Efficiency: 55% (excellent, top quartile)

- Operating Margin: 22% (strong)

- Current Ratio: 2.1 (healthy liquidity)

- Debt-to-Equity: 0.4 (conservative leverage)

- P/E Ratio: 16x (reasonable valuation)

This combination suggests a high-quality company with strong operations, solid profitability, financial safety, and reasonable valuation, an attractive investment candidate worthy of deeper research.

Conversely, a company with poor efficiency (operating efficiency 78%), weak margins (operating margin 6%), tight liquidity (current ratio 1.1), high leverage (debt-to-equity 2.5), and expensive valuation (P/E 25x) presents multiple red flags.

Insight: Efficiency ratios provide one lens for viewing company quality. The most complete understanding comes from analyzing efficiency alongside profitability, liquidity, leverage, and valuation metrics. Each ratio category reveals different aspects of financial health and investment attractiveness.

Understanding these relationships helps investors build comprehensive financial models and make better-informed decisions about capital allocation across their portfolios.

📊 Efficiency Ratio Calculator

Calculate and analyze different efficiency metrics for your business

Conclusion: Using Efficiency Ratios to Build Wealth Through Better Investing

Efficiency ratios reveal a fundamental truth about business: Companies that convert resources into revenue most effectively generate superior returns over time. The math behind money becomes clear when analyzing how much a business spends to generate each dollar of sales, how quickly it turns inventory into cash, and how effectively it deploys assets to create value.

For investors building wealth through evidence-based investing, efficiency ratios provide quantitative evidence of operational quality that complements valuation analysis and growth assessment. Companies maintaining efficiency advantages over competitors possess sustainable competitive moats that protect profitability and support long-term wealth creation.

Key principles for applying efficiency ratio analysis:

Start with industry context. A 50% efficiency ratio signals excellence for a bank but mediocrity for a software company. Always compare companies to industry peers and historical performance rather than applying universal standards.

Focus on trends, not snapshots. A single quarter’s efficiency ratio means little. Companies showing consistent efficiency improvement over multiple years demonstrate genuine operational progress. Deteriorating efficiency over several quarters provides an early warning of competitive or management problems.

Combine efficiency with profitability. The most attractive investments show both superior efficiency and strong margins. Companies that spend less to generate revenue while maintaining pricing power possess the strongest operational profiles.

Monitor efficiency in your portfolio. Track efficiency ratios quarterly for all holdings. Deteriorating efficiency often precedes earnings disappointments and stock price declines. Early detection enables proactive portfolio management.

Use efficiency to identify quality. When choosing between similar companies, favor those with superior efficiency ratios. Operational excellence compounds over time, creating sustainable advantages that drive long-term returns.

Understand the limitations. Efficiency ratios diagnose operational performance but don’t explain causes. Combine ratio analysis with business model understanding, competitive assessment, and management evaluation for comprehensive investment decisions.

The path to financial literacy and wealth building runs through understanding how businesses actually work—not just what they report in headline earnings. Efficiency ratios illuminate the operational reality behind financial statements, revealing which management teams allocate capital wisely and which waste resources on bloated operations.

Next steps for applying this knowledge:

- Calculate efficiency ratios for your current portfolio holdings and compare them to industry benchmarks

- Screen for efficiency leaders in sectors you’re interested in investing in

- Monitor efficiency trends quarterly to identify improving or deteriorating companies

- Build watchlists of companies showing consistent efficiency advantages over competitors

- Integrate efficiency analysis into your investment process alongside valuation and growth metrics

The companies that consistently convert inputs into outputs most effectively compound wealth for shareholders over decades. Understanding efficiency ratios provides the analytical framework to identify these exceptional businesses and avoid operational underperformers.

Mastering the math behind money means understanding not just what companies earn, but how efficiently they earn it. That knowledge transforms investing from speculation into systematic wealth building through operational excellence.

References

[1] Corporate Finance Institute. “Efficiency Ratio.” https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/accounting/efficiency-ratio/

[2] Investopedia. “Efficiency Ratio: Definition, Formula, and Example.” https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/efficiencyratio.asp

[3] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Bank Efficiency Ratios and Performance Metrics.” https://research.stlouisfed.org/

[4] CFA Institute. “Financial Statement Analysis: Activity Ratios.” https://www.cfainstitute.org/

[5] Morningstar. “Understanding Operational Efficiency Metrics.” https://www.morningstar.com/

[6] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “Financial Statement Analysis Guide.” https://www.sec.gov/investor/pubs/begfinstmtguide.htm

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform dedicated to teaching the math behind money. With expertise in financial analysis, valuation principles, and evidence-based investing, Max translates complex financial concepts into actionable insights for investors building long-term wealth. His analytical approach combines rigorous quantitative analysis with practical investment applications, helping readers understand not just what works in finance, but why it works.

Educational Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. The information presented represents general principles of financial analysis and should not be considered personalized investment recommendations. Efficiency ratios are analytical tools that require proper context and interpretation. Past performance and historical efficiency metrics do not guarantee future results. Different industries, business models, and economic conditions affect the interpretation and relevance of efficiency ratios. Before making any investment decisions, consult with qualified financial, tax, and legal professionals who understand your specific circumstances, risk tolerance, and financial objectives. The Rich Guy Math and its authors do not provide personalized investment advice and are not responsible for any financial decisions made based on this content.

Frequently Asked Questions About Efficiency Ratios

What is a good efficiency ratio?

A good efficiency ratio depends entirely on industry context. For banks, an efficiency ratio below 50% indicates excellent performance, while 50–60% represents good efficiency. For retailers, asset turnover above 2.0 and inventory turnover above 6.0 generally signal strong efficiency. Technology companies often show asset turnover exceeding 5.0 due to minimal physical assets. Always compare efficiency ratios to industry benchmarks and direct competitors rather than using absolute standards across all sectors.

How can a company improve its efficiency ratio?

Companies improve efficiency ratios through several operational levers: reducing operating expenses through automation and process improvements; improving asset utilization by selling underperforming assets or increasing capacity usage; accelerating inventory turnover through better demand forecasting and inventory management; speeding receivables collection through improved credit policies; and implementing working capital optimization programs. The most sustainable improvements come from systematic operational excellence rather than one-time cost cuts.

What’s the difference between efficiency ratio and operating margin?

The efficiency ratio measures what percentage of revenue gets consumed by operating expenses, while operating margin measures what percentage of revenue remains as operating profit. These metrics are inversely related—as efficiency ratio decreases (improves), operating margin increases. A company with a 60% efficiency ratio and 40% gross margin would show a 10% operating margin.

Can a company have too much efficiency?

Yes. Excessive focus on efficiency can lead to underinvestment in research and development, inadequate inventory levels causing stockouts, aggressive collection practices damaging customer relationships, and deferred maintenance creating future risks. Sustainable efficiency balances cost control with necessary investments in growth, innovation, and customer satisfaction.

How often should investors review efficiency ratios?

Review efficiency ratios quarterly when companies report earnings, but evaluate trends over multiple periods rather than single-quarter fluctuations. Seasonal businesses show natural quarterly variation. Annual analysis provides the clearest long-term view. For investors, monitor quarterly but make decisions based on multi-year efficiency patterns.

Do efficiency ratios work for evaluating small businesses?

Yes. Efficiency ratios are just as valuable for small businesses as for large corporations. Small businesses should track operating efficiency, asset turnover, inventory turnover, and receivables turnover to identify improvement opportunities. Ratios may be more volatile due to scale, but the fundamentals remain very useful.

What’s the relationship between efficiency ratios and cash flow?

Improving efficiency ratios typically enhances cash flow generation. Faster inventory turnover reduces cash tied up in stock. Quicker receivables collection converts sales to cash sooner. Better asset utilization generates more revenue without new capital investment. Companies with strong efficiency ratios often show healthier cash conversion cycles and more consistent free cash flow.