Taxes are required payments to government entities that fund public services, infrastructure, and programs—and understanding how they work is one of the most valuable financial skills anyone can develop.

Every dollar earned triggers a tax calculation. Every deduction claimed changes the outcome. Every bracket misunderstood costs money. The math behind taxes isn’t complicated, but the consequences of confusion are expensive.

Most people overpay because they don’t understand the progressive system. They fear raises because they think higher brackets consume entire paychecks. They miss credits worth thousands. They confuse marginal rates with effective rates and make decisions based on myths instead of mathematics.

This guide breaks down exactly how income taxes work in the United States, explains the progressive bracket system step-by-step, clarifies the critical difference between deductions and credits, and shows legal strategies to reduce your tax burden. The goal is simple: understand the system, keep more of what you earn, and make smarter financial decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Taxes use a progressive bracket system where only income within each bracket is taxed at that rate, not your entire income.

- Your marginal tax rate (highest bracket) is always higher than your effective tax rate (average rate paid)

- Tax deductions reduce taxable income before calculating taxes, while tax credits reduce taxes owed dollar-for-dollar

- Legal tax reduction strategies include maximizing retirement contributions, using HSAs, and timing income strategically.

- Common tax mistakes like confusing brackets and missing credits cost taxpayers thousands annually.

What Are Taxes?

Taxes are mandatory financial contributions that governments collect from individuals and businesses to fund public operations and services.

When you earn income, purchase goods, own property, or receive investment returns, various tax obligations arise. These payments aren’t optional—they’re legal requirements enforced by federal, state, and local authorities.

What Taxes Fund

Tax revenue supports infrastructure, education, defense, healthcare programs, emergency services, courts, regulatory agencies, and social safety nets. Without tax collection, governments couldn’t maintain roads, pay teachers, fund police departments, or operate Medicare.

The connection is direct: taxes paid → services received. The quality and quantity of public services correlate with tax revenue collected.

Federal vs State vs Local Taxes

The U.S. tax system operates on three levels:

Federal taxes are collected by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and fund national programs like Social Security, Medicare, defense, and federal agencies. Income tax is the largest federal revenue source.[1]

State taxes vary by location. Forty-three states impose income taxes, while seven (Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming) collect no state income tax. States also use sales taxes and property taxes.

Local taxes include city and county income taxes, property taxes, and special district assessments. These funds schools, police, fire departments, and municipal services.

Understanding this layered structure matters because your total tax burden combines all three levels. A high-income earner in California faces different total taxation than someone earning the same amount in Texas.

🔗 For broader context on managing all financial obligations, see personal finance fundamentals.

Takeaway: Taxes are required payments at multiple government levels that fund the services and infrastructure society depends on. The system is complex, but learnable—and learning it saves money.

How Income Taxes Actually Work (Step-by-Step)

Income taxes follow a specific calculation sequence. Understanding each step reveals exactly where tax-reduction opportunities exist.

Step 1: Earn Income

The process starts with gross income—all money received from wages, self-employment, investments, rental properties, and other sources. This is your total income before any adjustments.

Step 2: Calculate Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

Certain “above-the-line” deductions reduce gross income to create Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). These include:

- Contributions to traditional IRAs

- Student loan interest payments

- Health Savings Account (HSA) contributions

- Self-employment tax deductions

- Educator expenses

AGI is critical because it determines eligibility for many credits and deductions. Lower AGI = more tax benefits available.

Step 3: Subtract Deductions to Find Taxable Income

From AGI, subtract either the standard deduction or itemized deductions (whichever is larger).

For 2025, standard deductions are:[2]

- Single filers: $15,750

- Married filing jointly: $31,500

- Head of household: $23,625

The result is taxable income—the amount actually subject to tax rates.

Step 4: Apply Tax Brackets

Taxable income gets divided into brackets, with each portion taxed at its corresponding rate. This is where the progressive system operates (detailed in the next section).

Step 5: Subtract Tax Credits

After calculating the total tax from brackets, credits reduce the final amount owed. Credits are more valuable than deductions because they reduce taxes dollar-for-dollar.

Examples include:

- Child Tax Credit

- Earned Income Tax Credit

- Education credits

- Retirement Savers Credit

Step 6: Determine Final Tax Owed or Refund

Compare the total tax calculated to the amounts already withheld from paychecks throughout the year. If withholding exceeded the tax owed, you receive a refund. If withholding was insufficient, you owe the difference.

This six-step sequence applies to every tax return. Each step offers opportunities to reduce the final amount owed legally.

For a detailed explanation, see how income taxes work.

IRS Publication 17 – Your Federal Income Tax

Insight: The tax calculation isn’t a single multiplication—it’s a sequential process where strategic decisions at each step compound to create significant savings.

Federal Income Tax Brackets Explained

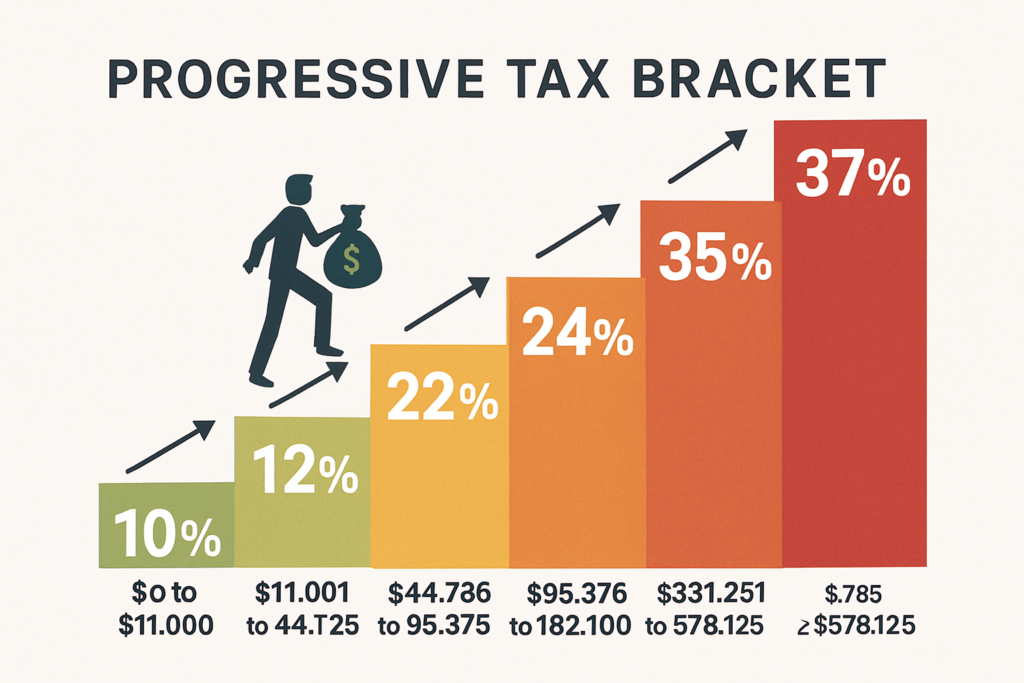

The United States uses a progressive tax system with seven marginal tax brackets. This structure is widely misunderstood, causing costly financial mistakes.

How Progressive Taxation Works

Progressive taxation means higher income is taxed at higher rates, but only the income within each bracket is taxed at that bracket’s rate. Your entire income is never taxed at your highest bracket rate.

Think of it as filling containers of different sizes, where each container has its own tax rate. You fill the first container before moving to the next.

2025 Federal Tax Brackets

For single filers in 2025:

| Tax Rate | Income Range |

|---|---|

| 10% | $0 to $11,925 |

| 12% | $11,926 to $48,475 |

| 22% | $48,476 to $103,350 |

| 24% | $103,351 to $197,300 |

| 32% | $197,301 to $250,525 |

| 35% | $250,526 to $626,350 |

| 37% | $626,351+ |

For married filing jointly in 2025:

| Tax Rate | Income Range |

|---|---|

| 10% | $0 to $23,850 |

| 12% | $23,851 to $96,950 |

| 22% | $96,951 to $206,700 |

| 24% | $206,701 to $394,600 |

| 32% | $394,601 to $501,050 |

| 35% | $501,051 to $751,600 |

| 37% | $751,601+ |

Real Example: How Brackets Actually Calculate

A single filer earning $70,000 in taxable income pays:

- 10% on first $11,925 = $1,192.50

- 12% on next $36,549 ($48,475 – $11,925) = $4,385.88

- 22% on remaining $21,525 ($70,000 – $48,475) = $4,735.50

Total tax: $10,313.88

Effective tax rate: $10,313.88 ÷ $70,000 = 14.7%

Notice the effective rate (14.7%) is significantly lower than the marginal rate (22%). This person is “in the 22% bracket” but doesn’t pay 22% on all income.

Common Bracket Myths Debunked

Myth: “Getting a raise that pushes me into a higher bracket means I’ll take home less money.”

Reality: Only the dollars above the bracket threshold are taxed at the higher rate. You always take home more with a higher income, just at a slightly reduced marginal rate on the excess.

Myth: “I’m in the 24% tax bracket, so I pay 24% of my income in taxes.”

Reality: You pay 24% only on income within that bracket. Your effective rate is much lower because earlier income is taxed at lower rates.

Annual Bracket Adjustments

The IRS adjusts bracket thresholds annually for inflation.[4] This prevents “bracket creep”—where inflation pushes taxpayers into higher brackets without real income increases.

For 2025, brackets increased approximately 2.8% from 2024 levels, reflecting inflation adjustments.

For current year details, see federal income tax brackets explained.

Takeaway: Progressive brackets tax income in layers, not as a whole. Understanding this structure prevents bad financial decisions based on bracket fear.

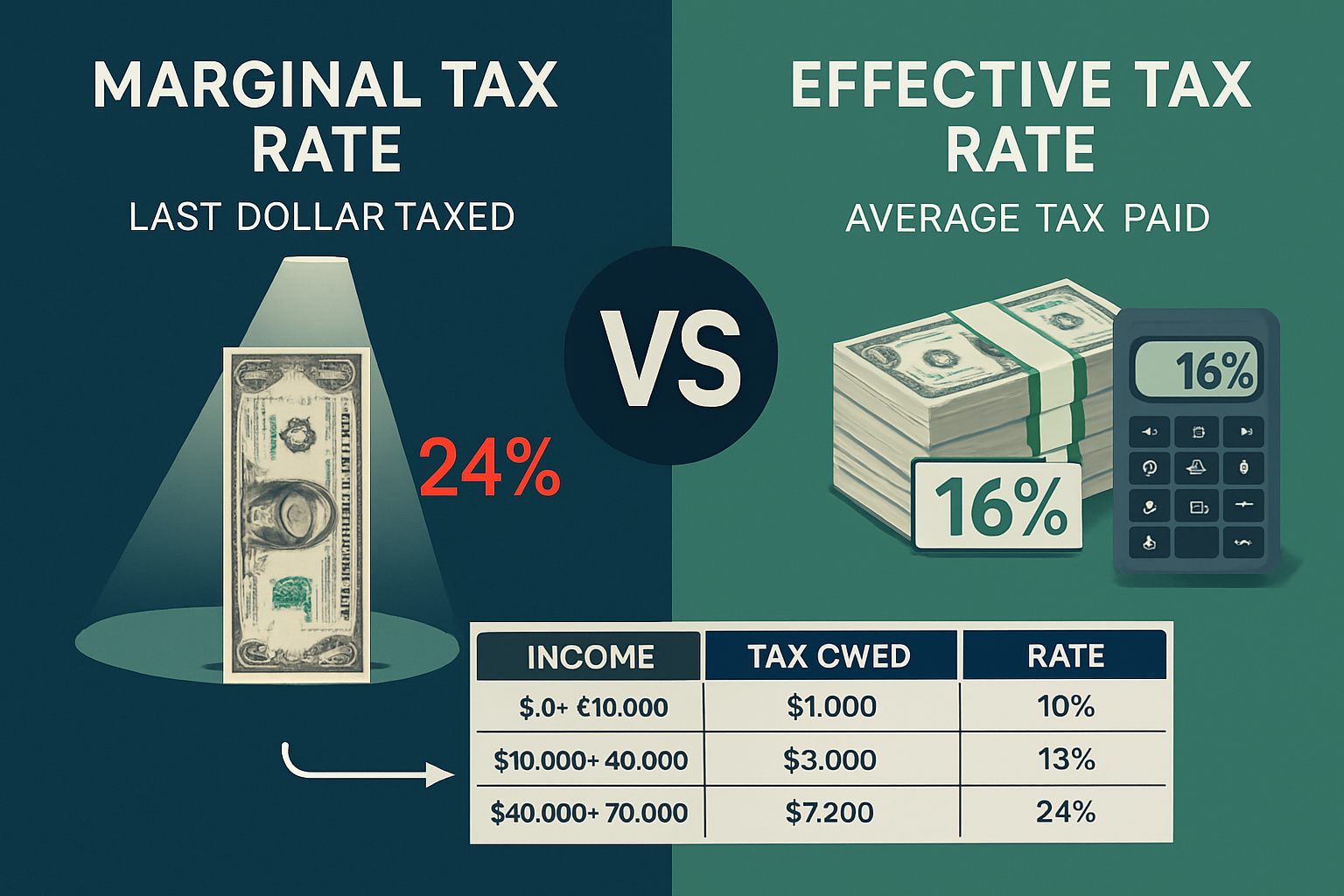

Marginal vs Effective Tax Rate

Confusing marginal and effective tax rates causes more bad financial decisions than almost any other tax misunderstanding.

Marginal Tax Rate Defined

Your marginal tax rate is the percentage applied to your last dollar of income. It’s the rate of your highest tax bracket.

If you’re a single filer with $70,000 taxable income, your marginal rate is 22%—because the last dollars earned fall in the 22% bracket.

This rate matters for incremental decisions:

- Should I work overtime?

- Should I take this bonus?

- What’s the tax cost of earning $1,000 more?

The answer involves your marginal rate because that additional income is taxed at your top bracket.

Effective Tax Rate Defined

Your effective tax rate is your total tax divided by your total income. It’s your average tax rate across all income levels.

Formula: Effective Rate = (Total Tax Owed ÷ Total Income) × 100

Using the earlier example:

- Income: $70,000

- Total tax: $10,313.88

- Effective rate: 14.7%

This rate represents your actual overall tax burden. It’s always lower than your marginal rate in a progressive system.

Why This Distinction Matters

Bad decision example: Refusing a $10,000 raise because “it’ll push me into the 24% bracket and I’ll lose money.”

Reality: Only income above the 24% threshold is taxed at 24%. The raise still increases take-home pay significantly.

Better decision framework: Use marginal rate for incremental decisions (should I earn more?) and effective rate for overall tax burden assessment (what percentage of income goes to taxes?).

Calculating Both Rates

Marginal rate: Look at your taxable income and identify which bracket it falls into. That bracket’s rate is your marginal rate.

Effective rate: Divide total tax by total income. This requires knowing your final tax amount after all calculations.

Decision-Making Applications

Retirement contributions: Deductible contributions save taxes at your marginal rate. Contributing $5,000 to a traditional 401(k) when your marginal rate is 22% saves $1,100 in taxes.

Roth vs Traditional: If you expect your effective rate in retirement to be lower than your current marginal rate, traditional retirement accounts often make mathematical sense.

Income timing: If you can control when income is recognized, shifting it to years with lower marginal rates reduces total tax.

Deep dive: marginal vs effective tax rate.

Insight: Your marginal rate tells you the cost of earning more; your effective rate tells you your overall burden. Both matter, but for different decisions.

Tax Deductions vs Tax Credits

Deductions and credits both reduce tax burden, but they work completely differently. Understanding the distinction reveals which opportunities provide the most value.

Tax Deductions Explained

Tax deductions reduce taxable income before tax is calculated. They lower the amount of income subject to taxation.

Value formula: Deduction Amount × Marginal Tax Rate = Tax Savings

A $1,000 deduction at a 22% marginal rate saves $220 in taxes.

Types of Deductions

Standard Deduction: Automatic reduction available to all taxpayers based on filing status.

2025 amounts:[5]

- Single: $15,750

- Married filing jointly: $31,500

- Head of household: $23,625

Itemized Deductions: Individual expenses that can be deducted if their total exceeds the standard deduction.

Common itemized deductions:

- Mortgage interest

- State and local taxes (SALT, capped at $10,000)

- Charitable contributions

- Medical expenses exceeding 7.5% of AGI

Above-the-Line Deductions: Reduce gross income to create AGI, available regardless of whether you itemize.

Examples:

- Traditional IRA contributions

- Student loan interest

- HSA contributions

- Self-employment tax deduction

Tax Credits Explained

Tax credits reduce tax owed dollar-for-dollar after tax is calculated. They’re more valuable than deductions.

Value: A $1,000 credit reduces taxes by exactly $1,000, regardless of tax bracket.

Types of Credits

Refundable Credits: Can reduce tax below zero, resulting in a refund.

Examples:

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

- Additional Child Tax Credit

- American Opportunity Tax Credit (partially refundable)

Nonrefundable Credits: Can reduce tax to zero but not below.

Examples:

- Child Tax Credit (up to $2,000 per child)

- Lifetime Learning Credit

- Retirement Savers Credit

- Adoption Credit

Value Comparison Example

Assume a 22% marginal tax rate:

$1,000 deduction value: $1,000 × 0.22 = $220 tax savings

$1,000 credit value: $1,000 tax savings

The credit is worth 4.5× more than the deduction in this scenario.

Strategic Priority

When planning tax reduction:

- Maximize credits first (higher value per dollar)

- Use above-the-line deductions (reduce AGI, expanding credit eligibility)

- Evaluate itemizing vs standard deduction (take whichever is larger)

- Time deductions strategically (bunch itemized deductions in alternating years if near standard deduction threshold)

🔗 Comprehensive guide: tax deductions vs tax credits.

Takeaway: Credits reduce taxes directly; deductions reduce taxable income. Credits are more valuable, but both play important roles in tax planning.

Common Types of Taxable Income

Not all income is taxed the same way. Understanding different income categories reveals planning opportunities.

Wages and Salaries (W-2 Income)

W-2 income is compensation from employers reported on Form W-2. This includes:

- Regular wages

- Salaries

- Tips

- Bonuses

- Commissions

Tax treatment: Taxed as ordinary income at your marginal rate. Subject to FICA taxes (Social Security and Medicare).

Employers withhold taxes throughout the year, reducing the amount you owe when filing.

Self-Employment Income (1099 Income)

1099 income includes payments to independent contractors, freelancers, and business owners reported on Form 1099-NEC or 1099-MISC.

Tax treatment: Taxed as ordinary income, but you also pay self-employment tax (15.3%) covering both employer and employee portions of FICA.

Advantage: Business expenses are deductible, reducing taxable income. You can also deduct half of the self-employment tax as an above-the-line deduction.

🔗 Understanding employment types: W-2 vs 1099 explained.

Interest and Dividend Income

Interest income from savings accounts, CDs, and bonds is reported on Form 1099-INT.

Tax treatment: Taxed as ordinary income at your marginal rate.

Dividend income from stocks comes in two types:

Ordinary dividends: Taxed as ordinary income.

Qualified dividends: Taxed at preferential capital gains rates (0%, 15%, or 20% depending on income).

To qualify, you must hold the stock for more than 60 days during the 121 days beginning 60 days before the ex-dividend date.[6]

Capital Gains

Capital gains are profits from selling assets like stocks, real estate, or businesses.

Short-term capital gains: Assets held one year or less, taxed as ordinary income.

Long-term capital gains: Assets held more than one year, taxed at preferential rates:

- 0% for income up to $48,350 (single) or $96,700 (married filing jointly)

- 15% for income up to $533,400 (single) or $600,050 (married filing jointly)

- 20% for income above those thresholds

The holding period creates significant tax differences. Selling after 366 days versus 364 days can reduce tax by more than half.

Rental Income

Income from rental properties is taxable, but expenses (mortgage interest, property taxes, repairs, depreciation) are deductible.

Net rental income (income minus expenses) is taxed as ordinary income.

Retirement Account Distributions

Traditional IRA/401(k) distributions: Taxed as ordinary income in the year withdrawn.

Roth IRA/401(k) distributions: Tax-free if the account is at least 5 years old and you’re over 59½.

Social Security benefits: Partially taxable depending on combined income (AGI + nontaxable interest + half of Social Security benefits).

Takeaway: Different income types face different tax treatments. Strategic income planning considers not just how much you earn, but what type of income you generate.

Capital Gains Tax Explained

Capital gains taxation significantly affects investment returns. Understanding the rules enables better investment timing and strategy.

What Triggers Capital Gains Tax

You realize a capital gain when you sell an asset for more than you paid. The gain is the difference between the sale price and the cost basis.

Example:

- Bought stock for $5,000

- Sold stock for $8,000

- Capital gain: $3,000

No tax is owed until you sell. Unrealized gains (paper gains) aren’t taxed.

Short-Term vs Long-Term Capital Gains

The holding period determines tax treatment:

Short-term capital gains: Assets held one year or less

- Taxed as ordinary income at your marginal rate

- Rates: 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, or 37%

Long-term capital gains: Assets held more than one year

- Taxed at preferential rates

- Rates: 0%, 15%, or 20%

2025 Long-Term Capital Gains Rates

0% rate:

- Single filers: Income up to $48,350

- Married filing jointly: Income up to $96,700

15% rate:

- Single filers: Income $48,351 to $533,400

- Married filing jointly: Income $96,701 to $600,050

20% rate:

- Single filers: Income above $533,400

- Married filing jointly: Income above $600,050

Why Holding Period Matters

The tax difference between short-term and long-term treatment is substantial.

Example: $10,000 capital gain, 24% marginal tax bracket

Short-term (held 11 months): $10,000 × 24% = $2,400 tax

Long-term (held 13 months): $10,000 × 15% = $1,500 tax

Savings from waiting 2 more months: $900

This creates a powerful incentive to hold investments longer than one year.

Capital Losses

Capital losses offset capital gains. If losses exceed gains, you can deduct up to $3,000 against ordinary income per year. Excess losses carry forward to future years.

Tax-loss harvesting involves strategically selling losing positions to offset gains, reducing tax owed while maintaining investment exposure.

Special Situations

Primary residence: Gains up to $250,000 (single) or $500,000 (married filing jointly) are tax-free if you lived in the home for 2 of the last 5 years.[7]

Collectibles: Gains on art, antiques, and precious metals are taxed at a maximum 28% rate.

Net Investment Income Tax: High earners pay an additional 3.8% Medicare tax on investment income when modified AGI exceeds $200,000 (single) or $250,000 (married filing jointly).

Complete guide: capital gains tax explained.

Insight: The calendar matters. Holding investments for at least one year before selling can reduce tax by more than half, directly increasing after-tax returns.

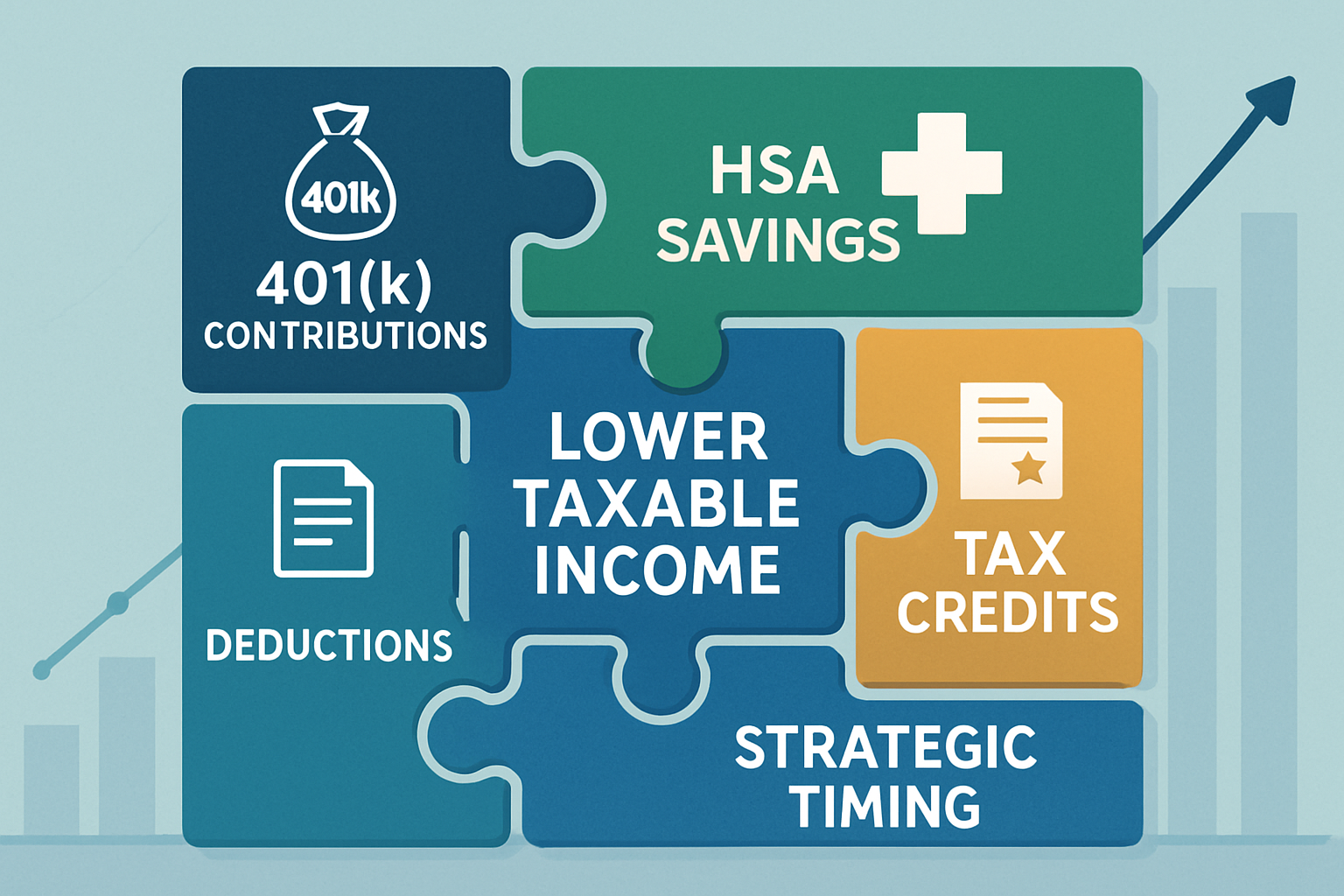

Legal Ways to Reduce Your Taxable Income

Strategic tax planning focuses on legal methods to reduce taxable income and lower tax owed. These strategies work within the tax code to minimize burden.

Maximize Retirement Contributions

Traditional 401(k) and 403(b) contributions reduce taxable income dollar-for-dollar.

2025 contribution limits:[8]

- Employee contribution: $23,500

- Age 50+ catch-up: Additional $7,500

- Total possible: $31,000

Tax savings: Contributing $23,500 at a 24% marginal rate saves $5,640 in current-year taxes.

Traditional IRA contributions also reduce taxable income if you meet income requirements.

2025 IRA contribution limit: $7,000 ($8,000 if age 50+)

Deductibility phases out at higher incomes if you’re covered by a workplace retirement plan.

Health Savings Account (HSA) Contributions

HSAs offer triple tax benefits:

- Contributions reduce taxable income

- Growth is tax-free

- Withdrawals for qualified medical expenses are tax-free

2025 HSA contribution limits:[9]

- Individual coverage: $4,300

- Family coverage: $8,550

- Age 55+ catch-up: Additional $1,000

Requirement: Must have a high-deductible health plan (HDHP).

HSAs are the most tax-advantaged accounts available. Unlike FSAs, funds roll over indefinitely.

Itemize Deductions When Beneficial

If itemized deductions exceed your standard deduction, itemizing saves money.

Strategy: Bunch deductions into alternating years to exceed the standard deduction threshold.

Example: Instead of donating $10,000 annually, donate $20,000 every other year. In donation years, itemize. In other years, take the standard deduction.

Common itemized deductions:

- Charitable contributions

- Mortgage interest

- State and local taxes (capped at $10,000)

- Medical expenses exceeding 7.5% of AGI

Contribute to 529 Education Savings Plans

While 529 contributions don’t reduce federal taxable income, many states offer state income tax deductions for contributions.

Earnings grow tax-free, and withdrawals for qualified education expenses are tax-free at the federal and state levels.

Qualified Business Income Deduction (QBI)

Self-employed individuals and business owners may deduct up to 20% of qualified business income from pass-through entities.[10]

This above-the-line deduction reduces taxable income without itemizing.

Limitations: Phase-outs apply at higher income levels, and specified service businesses face additional restrictions.

Strategic Income Timing

If you can control when income is recognized:

Defer income to next year if you expect to be in a lower tax bracket.

Accelerate income to this year if you expect higher rates next year.

Example: Self-employed individuals can delay invoicing in December to push income to January, deferring tax by one year.

Tax-Loss Harvesting

Sell investments with losses to offset gains. This reduces capital gains tax while allowing you to maintain market exposure by purchasing similar (but not identical) investments.

Wash sale rule: You can’t claim a loss if you repurchase the same security within 30 days before or after the sale.

Charitable Giving Strategies

Donate appreciated securities instead of cash. You avoid capital gains tax on appreciation and deduct the full fair market value.

Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs): If age 70½+, donate up to $105,000 annually from an IRA directly to charity. This satisfies required minimum distributions without increasing taxable income.

Avoid Aggressive or Gray-Area Strategies

Legal tax reduction differs from tax evasion. Strategies should be:

- Explicitly allowed by the tax code

- Properly documented

- Defensible in an audit

Avoid schemes promising “secret” deductions or strategies that seem too good to be true. They usually are.

Takeaway: Dozens of legal strategies reduce taxable income. The key is understanding which apply to your situation and implementing them systematically.

Common Tax Mistakes That Cost People Money

Tax errors cost taxpayers billions annually. Most mistakes stem from misunderstanding the system rather than intentional fraud.

Mistake #1: Confusing Marginal and Effective Rates

The error: Believing your entire income is taxed at your highest bracket rate.

The cost: Bad financial decisions like refusing raises, avoiding overtime, or not pursuing higher income.

The fix: Understand progressive taxation. Calculate both marginal and effective rates. Make decisions based on actual tax impact, not bracket fear.

Mistake #2: Missing Valuable Tax Credits

The error: Not claiming credits you’re eligible for because you don’t know they exist.

Common missed credits:

- Earned Income Tax Credit (worth up to $7,830 for families)

- Child Tax Credit ($2,000 per qualifying child)

- Retirement Savers Credit (up to $1,000)

- Education credits (up to $2,500)

The cost: Thousands of dollars in unclaimed tax reduction.

The fix: Review IRS credit eligibility each year. Use tax software that prompts for credits, or work with a tax professional.

Mistake #3: Not Adjusting Withholding

The error: Treating tax refunds as “free money” or bonuses.

The reality: Refunds mean you overpaid taxes all year, giving the government an interest-free loan.

The cost: Lost opportunity to invest or pay down debt with that money throughout the year.

The fix: Adjust W-4 withholding to match actual tax liability. Aim for a small refund or small amount owed—not thousands either way.

Calculate optimal withholding: take-home pay calculator.

Mistake #4: Ignoring Self-Employment Taxes

The error: Freelancers and contractors forgetting they owe both income tax and self-employment tax (15.3%).

The cost: Unexpected tax bills, penalties, and interest.

The fix: Set aside 25-30% of self-employment income for taxes. Make quarterly estimated tax payments to avoid underpayment penalties.

Mistake #5: Not Tracking Deductible Expenses

The error: Failing to document business expenses, charitable donations, medical expenses, and other deductible items.

The cost: Paying taxes on income that could have been offset by deductions.

The fix: Use expense tracking apps. Save receipts. Document mileage. Maintain organized records throughout the year.

Mistake #6: Filing Late Without Extension

The error: Missing the April 15 deadline without filing for an automatic extension.

The cost: Late filing penalty (5% of unpaid taxes per month, up to 25%) plus late payment penalty (0.5% per month) plus interest.

The fix: File Form 4868 for an automatic 6-month extension. Note: Extension to file isn’t an extension to pay—pay estimated taxes by April 15.

Mistake #7: Not Contributing to Tax-Advantaged Accounts

The error: Failing to maximize 401(k), IRA, and HSA contributions.

The cost: Paying unnecessary taxes on income that could have been sheltered.

The fix: Contribute at least enough to get the employer’s 401(k) match. Maximize HSA if eligible. Increase contributions annually.

Mistake #8: Overlooking State Tax Differences

The error: Not considering state tax implications when relocating or earning remote income.

The cost: Higher overall tax burden from living in high-tax states when lower-tax options exist.

The fix: Research state tax rates when considering relocation. Understand state tax treatment of remote work and retirement income.

Mistake #9: Selling Investments Before One Year

The error: Selling winning investments before the one-year holding period, triggering short-term capital gains.

The cost: Paying ordinary income tax rates instead of lower long-term capital gains rates.

The fix: Track purchase dates. Wait until day 366 to sell appreciated positions unless compelling reasons exist.

Mistake #10: Not Seeking Professional Help When Needed

The error: Using basic tax software for complex situations (business income, rental properties, stock options, multiple states).

The cost: Missed deductions, incorrect filings, and potential audit issues.

The fix: Work with a CPA or Enrolled Agent for complex returns. The fee often pays for itself in tax savings.

Takeaway: Most tax mistakes are preventable through education and attention to detail. The cost of errors far exceeds the effort required to avoid them.

Tax Tools and Calculators That Help

Strategic tax planning requires accurate calculations. These tools provide clarity and support better decisions.

IRS Free File

The IRS offers free tax preparation software for taxpayers earning less than $79,000.[11]

Features:

- Guided tax preparation

- Free federal filing

- Some include free state filing

- Automatic calculation of credits and deductions

Access: IRS.gov/freefile

Tax Bracket Calculators

Tax bracket calculators show which brackets your income falls into and calculate estimated tax owed.

What they reveal:

- Marginal tax rate

- Effective tax rate

- Tax owed by bracket

- Impact of additional income

Calculate your brackets: tax bracket calculator.

Take-Home Pay Calculators

Paycheck calculators estimate net pay after federal, state, and FICA taxes.

Use cases:

- Evaluating job offers

- Adjusting withholding

- Budgeting with accurate net income

- Comparing salary changes

Estimate your net pay: take-home pay calculator.

Retirement Contribution Calculators

These tools calculate tax savings from 401(k) and IRA contributions.

Inputs:

- Current income

- Contribution amount

- Tax bracket

Outputs:

- Current year tax savings

- Future account value

- Tax-deferred growth

Capital Gains Tax Calculators

Capital gains calculators estimate tax on investment sales.

Features:

- Short-term vs long-term comparison

- State tax inclusion

- Net investment income tax calculation

- After-tax proceeds

HSA Contribution Calculators

HSA calculators show tax savings from contributions and project account growth.

Benefits shown:

- Current year tax reduction

- Future tax-free growth

- Retirement healthcare funding

Tax Withholding Estimator

The IRS Tax Withholding Estimator helps adjust W-4 settings to match actual tax liability.[12]

Purpose: Avoid large refunds (overwithholding) or unexpected tax bills (underwithholding).

Process:

- Enter income and deductions

- Review projected tax

- Receive W-4 recommendations

- Submit updated W-4 to employer

Access: IRS.gov/W4App

Professional Tax Software

Comprehensive tax software (TurboTax, H&R Block, TaxAct) guides preparation and maximizes deductions.

Features:

- Interview-style questions

- Automatic form selection

- Error checking

- Audit support

- Prior year import

Cost: $0-$200+ depending on complexity

Takeaway: Calculators and tools transform tax planning from guesswork to precision. Use them to model scenarios before making financial decisions.

How Taxes Fit Into Your Bigger Financial Plan

Taxes aren’t isolated—they affect every financial decision and interact with all aspects of wealth building.

Taxes Affect Cash Flow

Your after-tax income determines how much you can save, invest, and spend. Understanding true take-home pay enables realistic budgeting.

Planning consideration: When evaluating raises, bonuses, or new jobs, calculate after-tax income change, not just gross income change.

Taxes Impact Investment Returns

Investment returns are measured after taxes. A 10% pre-tax return becomes 7.8% after 22% tax, or 8.5% with preferential long-term capital gains treatment.

Planning consideration: Tax-efficient investing—using tax-advantaged accounts, holding investments long-term, and locating assets strategically—increases compound growth.

Taxes Influence Retirement Planning

Retirement account choices (traditional vs Roth) depend on current versus expected future tax rates.

Traditional accounts: Tax deduction now, taxed later

Roth accounts: No deduction now, tax-free later

Planning consideration: If your marginal rate now exceeds your expected effective rate in retirement, traditional accounts often make mathematical sense.

Taxes Affect Giving Strategies

Charitable giving creates tax deductions, but timing and method matter.

Planning consideration: Donating appreciated securities provides better tax outcomes than donating cash, and bunching donations in alternating years can exceed standard deduction thresholds.

Taxes Shape Business Decisions

Business structure (sole proprietorship, LLC, S-corp, C-corp) creates different tax treatments.

Planning consideration: Self-employment tax, qualified business income deduction, and entity taxation should influence structure decisions.

Planning Beats Reacting

Reactive approach: File taxes in April based on last year’s decisions.

Proactive approach: Make financial decisions throughout the year with tax implications in mind.

The difference: Thousands of dollars in legal tax reduction.

Every Major Money Decision Has Tax Impact

Consider tax implications before:

- Accepting job offers

- Selling investments

- Withdrawing retirement funds

- Starting businesses

- Buying or selling real estate

- Getting married or divorced

Tax planning isn’t separate from financial planning—it’s integrated throughout.

Takeaway: Taxes are a variable you can influence through strategic planning. Integrating tax awareness into all financial decisions compounds savings over time.

2025 Federal Tax Calculator

Calculate your marginal vs effective tax rate

Conclusion

Taxes operate on mathematical principles that reward understanding and punish confusion.

The progressive bracket system doesn’t punish higher earners as severely as most believe—it taxes income in layers, creating effective rates far below marginal rates. Deductions reduce taxable income before calculations begin. Credits reduce taxes owed dollar-for-dollar. Legal strategies exist at every income level to reduce tax burden.

The cost of tax ignorance is measurable: thousands paid each year unnecessarily, opportunities missed, decisions made based on myths rather than mathematics.

The benefit of tax literacy is equally measurable: more money kept, better financial decisions, and confidence in understanding how the system works.

Action steps:

- Calculate your effective tax rate to understand your actual burden

- Maximize contributions to 401(k), IRA, and HSA accounts before year-end

- Review eligible credits you may have missed in previous years

- Adjust withholding if you consistently receive large refunds or owe significant amounts

- Track deductible expenses throughout the year, not just at tax time

- Consider professional help if your situation involves business income, investments, or multiple states

Taxes are complex, but learnable. The math behind them is accessible. The strategies to reduce them legally are available to everyone.

Understanding taxes isn’t just about paying less—it’s about making informed financial decisions that compound over decades. Every dollar saved in taxes is a dollar that can be invested, creating compound growth that multiplies the initial savings.

The tax code rewards those who understand it. Start learning. Start planning. Start keeping more of what you earn.

Related Guides

- Understanding tax brackets and how they work

- Strategies for reducing taxable income legally

- Common tax deductions most people miss

- How tax refunds really work and what they mean

References

[1] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Federal Income Tax.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/

[2] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “IRS Provides Tax Inflation Adjustments for Tax Year 2025.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/

[3] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “2025 Tax Brackets and Federal Income Tax Rates.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/

[4] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Cost-of-Living Adjustments.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/

[5] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Standard Deduction Amounts.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/

[6] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Publication 550 – Investment Income and Expenses.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p550

[7] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Publication 523 – Selling Your Home.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p523

[8] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “401(k) Contribution Limits.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/

[9] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Health Savings Account Contribution Limits.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/

[10] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Qualified Business Income Deduction.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/

[11] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “IRS Free File.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/freefile

[12] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Tax Withholding Estimator.” IRS.gov. https://www.irs.gov/W4App

Disclaimer

This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute tax advice, legal advice, or financial advice. Tax laws are complex and change frequently. Individual circumstances vary significantly, and what applies to one taxpayer may not apply to another.

The information provided represents general tax concepts and should not be relied upon for making specific tax decisions. Always consult with a qualified tax professional, Certified Public Accountant (CPA), or Enrolled Agent before making tax-related decisions or filing tax returns.

The Rich Guy Math and its authors are not liable for any actions taken based on information in this article. Tax regulations, brackets, deduction amounts, and credit eligibility change annually and may differ from the information presented here.

For official tax guidance, consult IRS publications or seek professional tax advice tailored to your specific situation.

About the Author

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a financial education platform dedicated to explaining the mathematics behind money with clarity and precision. With a background in financial analysis and data-driven decision-making, Max specializes in breaking down complex financial concepts into actionable insights.

Max’s approach combines analytical rigor with educational accessibility, helping readers understand not just what to do with money, but why specific strategies work mathematically. His focus areas include tax optimization, investment fundamentals, compound growth principles, and evidence-based wealth building.

The Rich Guy Math provides educational content grounded in data, logic, and financial mathematics—never marketing hype or unsubstantiated claims. Every article aims to increase financial literacy through clear explanations of how money actually works.

Connect with Max and explore more financial education at TheRichGuyMath.com.