Budgeting and saving represent the foundational math behind money management—budgeting means assigning every dollar a specific purpose before spending it, while saving means systematically setting aside money for future needs and opportunities. Together, these two practices form the bedrock of financial control and wealth accumulation.

Most people approach money reactively, spending first and hoping something remains at the end. This backward approach explains why 40% of Americans cannot cover a $400 emergency expense without borrowing money[1]. The evidence is clear: without deliberate budgeting and saving strategies, financial stress becomes inevitable regardless of income level.

The math behind effective budgeting and saving is straightforward—track what comes in, control what goes out, and systematically redirect the difference toward future goals. This simple equation creates the foundation for every wealth-building strategy that follows, from emergency funds to investment portfolios to retirement security.

This guide explains how budgeting and saving work together, why they matter more than income alone, and how to implement proven frameworks that transform financial chaos into systematic wealth building.

Key Takeaways

- Budgeting assigns purpose to every dollar before spending occurs, preventing the reactive money management that creates financial stress.

- Saving must happen first, not last—automated transfers to savings accounts before discretionary spending ensures consistency.

- The 50/30/20 rule provides a simple starting framework: 50% needs, 30% wants, 20% savings and debt repayment.

- Emergency savings of 3-6 months’ expenses create financial resilience that prevents debt reliance during unexpected events.

- Budgeting and saving are step one, not the destination—they create the foundation for investing, compound growth, and long-term wealth building.

What Is Budgeting and Saving?

Budgeting means telling your money where to go instead of wondering where it went. The practice involves creating a written plan that assigns every dollar of income to a specific category: housing, food, transportation, savings, debt repayment, or discretionary spending before the month begins.

Saving means paying your future self first by systematically setting aside money before spending on current wants. This reverses the common pattern of spending freely and saving whatever remains (which is typically nothing).

Why these concepts work together, not separately:

Budgeting without saving creates detailed tracking of consumption but builds no financial security. Saving without budgeting often fails because uncontrolled spending in other categories eliminates the capacity to save consistently.

The combination creates a complete system: budgeting identifies where money currently goes and where it should go, while saving ensures that future-focused categories receive funding before present-focused spending depletes available resources.

Consider the cause-and-effect relationship: A person earning $4,000 monthly who budgets $800 for savings (20%) but doesn’t track other spending will likely overspend on wants, leaving no actual savings. Conversely, someone who saves $800 automatically on payday, then budgets the remaining $3,200 across all other categories, guarantees the savings goal gets met.

The mathematical relationship:

Income - Savings - Fixed Expenses - Variable Expenses = Zero (in zero-based budgeting)This equation forces intentionality. Every dollar receives an assignment. Nothing gets spent unconsciously.

Takeaway: Budgeting provides the structure; saving provides the purpose. Together, they transform income into wealth-building capacity rather than merely consumption.

For a deeper understanding of how these concepts fit within broader money management, explore personal finance fundamentals.

Why Budgeting and Saving Matter More Than You Think

The Federal Reserve’s 2024 Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households revealed that 37% of adults would struggle to cover a $400 emergency expense using cash or savings[1]. This statistic demonstrates a structural problem: most people lack the financial buffer that budgeting and saving create.

Budgeting and saving reduce financial stress through predictability:

Financial stress stems primarily from uncertainty, not knowing if money will last until the next paycheck, worrying about unexpected expenses, or feeling out of control. A budget eliminates this uncertainty by creating a written plan that shows exactly how much money is available for each category.

Research from the American Psychological Association shows that money consistently ranks as the top source of stress for Americans[2]. The antidote is control, and control comes from knowing where every dollar goes.

These practices prevent debt reliance:

Without savings, unexpected expenses (car repairs, medical bills, home maintenance) must be funded through credit cards or loans. This creates a debt cycle where interest payments consume future income, making saving even harder.

The math is unforgiving: A $2,000 emergency charged to a credit card at 18% APR takes 11 years to repay with minimum payments and costs $1,934 in interest[3]. The same emergency covered by existing savings costs zero in interest and creates no future payment obligations.

Budgeting and saving create investing readiness:

Wealth building through investing requires available capital. Without systematic saving, no capital accumulates. The opportunity cost is substantial every year without invested savings is a year without compound growth.

Consider this example: A 25-year-old who saves and invests $500 monthly at 8% average annual returns accumulates $1,745,503 by age 65. Delaying until age 35 reduces the total to $745,179—a difference of exactly $1,000,324 despite only 10 additional years[4].

Emergency resilience provides freedom:

An emergency fund of 3-6 months of expenses creates options during job loss, health issues, or family emergencies. This buffer allows for better decision-making rather than panic-driven choices.

The data on emergency savings:

According to Bankrate’s 2024 Annual Emergency Savings Report, only 44% of Americans could cover a $1,000 emergency expense from savings[5]. This means 56% would need to borrow, reduce spending in other categories, or leave the expense unpaid.

Takeaway: Budgeting and saving matter because they create the foundation for every other financial goal—debt freedom, investment growth, career flexibility, and retirement security. Without this foundation, higher income simply funds higher consumption rather than wealth building.

Popular Budgeting Methods

Multiple budgeting frameworks exist because different approaches work better for different income patterns, personalities, and financial goals. The following methods represent the most effective and widely used systems.

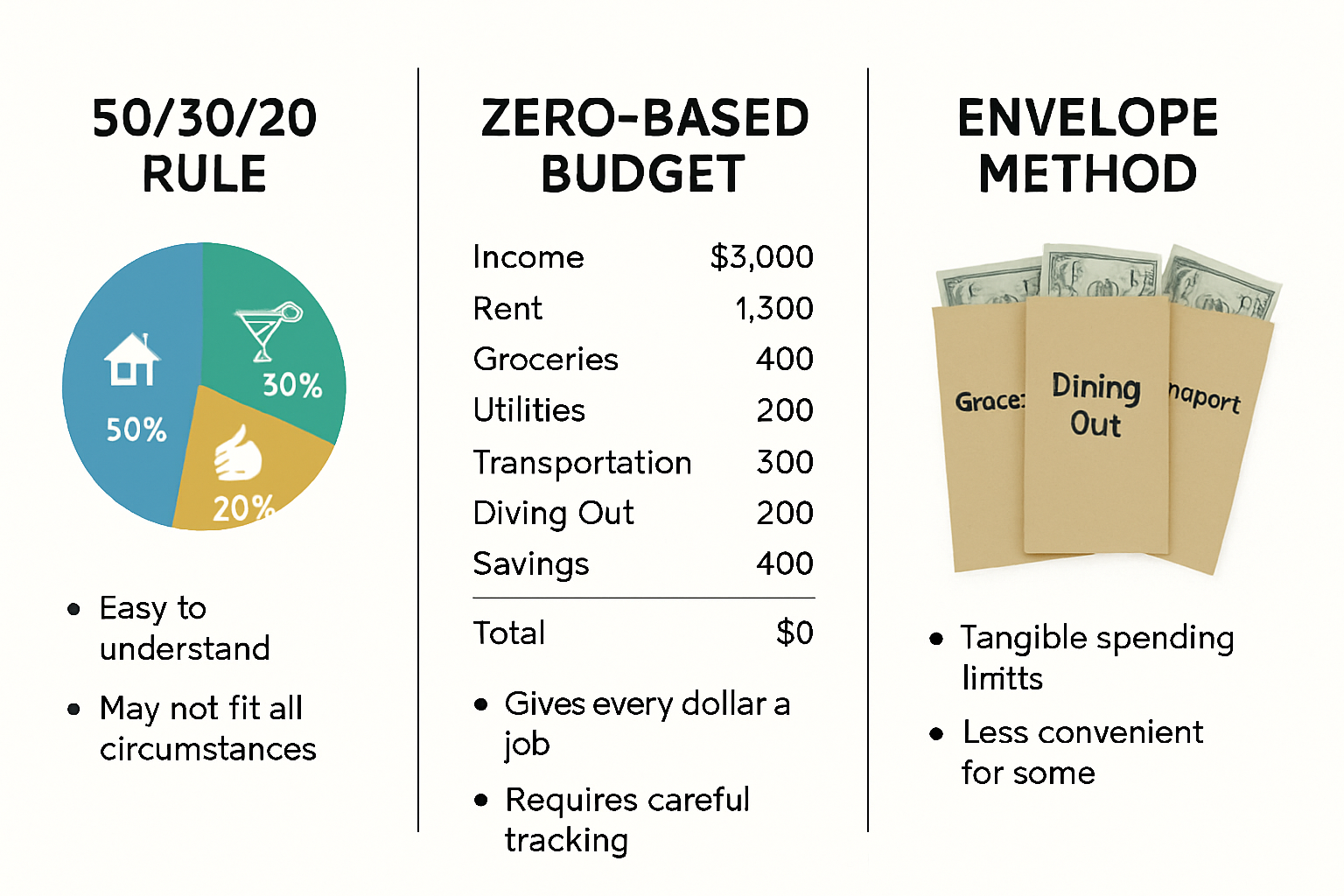

50/30/20 Budget Rule

The 50/30/20 rule divides after-tax income into three categories: 50% for needs, 30% for wants, and 20% for savings and debt repayment. This percentage-based approach was popularized by Senator Elizabeth Warren in her book “All Your Worth.”

How it works:

- 50% Needs: Essential expenses including housing, utilities, groceries, transportation, insurance, and minimum debt payments

- 30% Wants: Discretionary spending, including dining out, entertainment, hobbies, subscriptions, and non-essential purchases

- 20% Savings/Debt: Emergency fund contributions, retirement savings, extra debt payments, and investment contributions

Who it’s best for:

This method works well for people with stable, predictable income who want a simple framework without detailed category tracking. It provides clear guidelines while allowing flexibility within each broad category.

Pros:

- Simple to understand and implement

- Flexible within each category

- Automatically prioritizes savings (20% minimum)

- Works at any income level when percentages are maintained

Cons:

- May not work in high-cost-of-living areas where needs exceed 50%

- Requires discipline to accurately classify needs versus wants

- Doesn’t provide detailed spending insights within categories

- May allow overspending if wants consistently reach the 30% limit

The math:

For someone earning $5,000 monthly after taxes:

- Needs budget: $2,500

- Wants budget: $1,500

- Savings/debt: $1,000

Learn more about implementing this framework at the 50/30/20 budget rule.

Zero-Based Budgeting

Zero-based budgeting assigns every dollar of income to a specific category until the income minus all allocations equals zero. This doesn’t mean spending everything; savings and investments are categories that receive allocations.

How it works:

List all income sources, then assign every dollar to categories (including savings) until no unassigned money remains. The equation is:

Income - (All Category Allocations) = 0Best for variable income:

This method excels for freelancers, commission-based workers, or anyone with irregular income because it forces intentional decisions about every dollar earned, regardless of amount.

Control-focused approach:

Zero-based budgeting provides maximum visibility and control. Every dollar has a job, eliminating unconscious spending and ensuring alignment between spending and priorities.

Pros:

- Complete visibility into all spending

- Forces intentional decision-making

- Adapts to variable income

- Identifies waste quickly

- Aligns spending with values

Cons:

- Requires detailed tracking

- More time-intensive than percentage methods

- Can feel restrictive initially

- Requires monthly adjustments

Implementation example:

Monthly income: $4,200

Category allocations:

- Rent: $1,200

- Utilities: $150

- Groceries: $400

- Transportation: $300

- Insurance: $200

- Debt payment: $400

- Emergency savings: $300

- Retirement: $500

- Entertainment: $250

- Dining out: $200

- Clothing: $100

- Personal care: $100

- Miscellaneous: $100

- Total: $4,200 (equals income, zero remaining)

Explore the detailed implementation of a zero-based budget.

Other Common Budgeting Approaches

Envelope Method:

This cash-based system involves withdrawing budgeted amounts for variable categories (groceries, entertainment, dining) and placing cash in labeled envelopes. When an envelope is empty, spending in that category stops until the next budget period.

The envelope method creates tangible spending limits and prevents overspending through physical constraints. It works best for people who struggle with credit card overspending, but it becomes impractical for online purchases or bills requiring electronic payment.

Pay-Yourself-First:

This approach prioritizes savings by automatically transferring a set amount or percentage to savings accounts immediately when income is received. All other spending happens with what remains.

The psychological advantage is significant: saving becomes non-negotiable rather than dependent on leftover money. This method works exceptionally well when combined with automated transfers that remove the decision from conscious thought.

Values-Based Budgeting:

This framework starts by identifying core values (family, health, education, experiences), then aligns spending categories with those values. Categories supporting core values receive generous allocations, while spending misaligned with values gets reduced or eliminated.

Values-based budgeting creates motivation for budget adherence because spending restrictions feel purposeful rather than punitive. Someone who values travel might allocate 15% of income to a travel fund while minimizing spending on possessions that don’t align with their values.

Takeaway: The best budgeting method is the one you’ll actually use consistently. Start with the framework that matches your income pattern and personality, then adjust based on results.

Needs vs Wants — The Foundation of Every Budget

Budget failure often stems from misclassifying wants as needs. This psychological tendency inflates the “essential” spending category and leaves insufficient resources for savings and true priorities.

Why overspending is psychological:

Human brains are wired for immediate gratification. Marketing, social comparison, and lifestyle inflation all push toward increased consumption. Without conscious classification of expenses, wants gradually migrate into the needs category through rationalization.

Common rationalizations include:

- “I need this for work” (when a less expensive option exists)

- “I deserve this” (conflating reward with necessity)

- “Everyone has this” (social pressure masquerading as need)

- “It’s on sale” (discount doesn’t transform want into need)

How classification fixes budget failure:

Creating clear definitions for needs versus wants removes emotional decision-making from spending choices. The classification happens during budget creation, not at the point of purchase, when willpower is lowest.

Needs definition:

Needs are expenses required for survival, safety, and basic functioning in society. These include:

- Housing (rent or mortgage)

- Utilities (electricity, water, heat)

- Basic groceries

- Essential transportation

- Required insurance

- Minimum debt payments

- Basic clothing

- Essential healthcare

Wants definition:

Wants are expenses that enhance life quality but aren’t required for basic functioning. These include:

- Dining at restaurants

- Entertainment and hobbies

- Premium subscriptions

- Designer clothing

- Upgraded housing beyond basic needs

- New vehicles when functional ones exist

- Luxury groceries

- Non-essential technology

The gray area:

Some expenses fall between clear needs and wants. A car might be a need for commuting, but a $50,000 vehicle when a $20,000 one serves the same purpose represents $30,000 of want spending.

The solution: Classify the baseline as a need and the upgrade as a want. This allows budgeting for both while maintaining honest categorization.

Real-life examples:

Example 1 – Housing:

- Need: Safe, functional housing in a reasonable location

- Want: Luxury apartment with premium amenities in the most desirable neighborhood

- Budget approach: Allocate for adequate housing (need), then decide if the budget allows upgrading (want)

Example 2 – Food:

- Need: Nutritious groceries prepared at home

- Want: Regular restaurant meals and premium/organic products

- Budget approach: Ensure grocery budget covers healthy basics, then allocate discretionary funds to dining out

Example 3 – Phone:

- Need: Functional smartphone with a basic plan for communication

- Want: Latest flagship phone with an unlimited premium data plan

- Budget approach: Budget for adequate phone service, then evaluate if the wants category allows upgrades

The classification test:

Ask three questions:

- Would I face serious negative consequences without this expense?

- Does a less expensive alternative exist that meets the core requirement?

- Am I justifying this expense emotionally rather than logically?

If the answer to question 1 is no, it’s a want. If the answer to question 2 is yes, the upgrade portion is a want. If the answer to question 3 is yes, it’s likely a want.

Takeaway: Honest classification of needs versus wants creates budget realism. This doesn’t mean eliminating all wants—it means funding wants intentionally from the appropriate category rather than disguising them as needs and wondering why savings never accumulate.

For a deeper exploration of this concept, visit needs vs wants.

Saving Money the Right Way

The “save what’s left over” approach fails mathematically. Human spending expands to consume available resources—a principle known as Parkinson’s Law applied to finances. If money is available, it gets spent.

Why “saving leftovers” fails:

Consider two scenarios:

Scenario A (Leftover Saving):

- Income: $4,000

- Spending throughout the month: $3,850

- Amount saved: $150

- Savings rate: 3.75%

Scenario B (Pay Yourself First):

- Income: $4,000

- Automatic savings transfer on payday: $800

- Available for spending: $3,200

- Spending throughout the month: $3,200

- Amount saved: $800

- Savings rate: 20%

The difference is $650 monthly or $7,800 annually. Over 30 years at 8% returns, this difference compounds to $896,476 versus $168,589—a gap of $727,887[6].

The behavioral economics explanation:

Mental accounting research by Richard Thaler shows that people treat money differently based on its source and designated purpose[7]. Money already moved to savings gets mentally categorized as “unavailable,” reducing the temptation to spend it.

Conversely, money sitting in checking accounts feels available, triggering spending impulses.

Automating savings:

Automation removes willpower from the equation. Set up automatic transfers from checking to savings accounts on the same day income deposits occur.

Implementation steps:

- Calculate target savings amount (20% of income is a strong baseline)

- Set up an automatic transfer for that amount on payday

- Budget all other expenses using the remaining amount

- Adjust spending categories to fit within remaining funds

Short-term vs long-term savings:

Different savings goals require different account structures:

Short-term savings (0-2 years):

- Emergency fund (3-6 months expenses)

- Irregular expense fund (car maintenance, insurance premiums, gifts)

- Planned purchases (furniture, appliances, technology)

- Account type: High-yield savings account for liquidity and safety

Medium-term savings (2-5 years):

- Down payment for a home

- Vehicle purchase

- Wedding expenses

- Career transition fund

- Account type: High-yield savings or conservative investment account, depending on timeline certainty

Long-term savings (5+ years):

- Retirement contributions

- Children’s education

- Wealth building

- Account type: Tax-advantaged investment accounts (401k, IRA, 529)

The allocation strategy:

Divide total savings percentage across timeframes based on priorities:

Example for someone saving 20% of $5,000 monthly income ($1,000 total savings):

- Emergency fund: $400 (until fully funded)

- Retirement: $500 (ongoing)

- Down payment fund: $100 (ongoing)

Once the emergency fund reaches the target (e.g., $15,000), redirect that $400 to other goals.

Takeaway: Effective saving requires treating it as the first expense, not the last. Automation ensures consistency regardless of willpower, while separating accounts by timeframe prevents short-term needs from depleting long-term goals.

Learn more about building your foundation at Emergency Fund Basics.

How Much Should You Save Each Month?

The optimal savings rate depends on income level, expenses, debt obligations, and financial goals. However, research-based guidelines provide useful starting points.

Percentage-based guidance:

Financial planners typically recommend saving 20% of gross income as a baseline. This aligns with the 50/30/20 rule and provides sufficient capital for both emergency reserves and long-term wealth building.

The breakdown of 20%:

- 3-5%: Emergency fund (until fully funded)

- 10-15%: Retirement savings

- 2-5%: Other goals (home down payment, education, etc.)

Income-based flexibility:

Lower incomes may require modified percentages:

Income under $40,000:

- Target: 10-15% savings rate

- Priority: Emergency fund first, then retirement

- Strategy: Start with any amount, increase by 1% every 6 months

Income $40,000-$75,000:

- Target: 15-20% savings rate

- Priority: Emergency fund and retirement simultaneously

- Strategy: Maximize employer 401 (k) match, then build an emergency fund

Income $75,000-$150,000:

- Target: 20-25% savings rate

- Priority: Maximize tax-advantaged accounts

- Strategy: Max 401 (k) contributions, fund IRAs, build taxable investments

Income over $150,000:

- Target: 25-35%+ savings rate

- Priority: Tax optimization and wealth building

- Strategy: Max all tax-advantaged space, invest in taxable accounts, consider real estate

Age-based considerations:

Starting age significantly impacts the required savings rate for retirement:

- Age 25: 15% savings rate supports a comfortable retirement

- Age 35: 20% savings rate needed to catch up

- Age 45: 30%+ savings rate required for the same outcome

- Age 55: 40%+ savings rate necessary if starting from zero

The math behind this: compound growth requires time. Starting earlier allows smaller contributions to grow into larger sums. Starting later requires larger contributions to compensate for lost compounding years.

Why consistency beats perfection:

Saving 15% consistently for 40 years produces better outcomes than saving 25% sporadically. The key variable is time in market, not timing the market or perfect execution.

Example comparison:

Consistent saver:

- Saves $500/month for 30 years

- Never misses a month

- Total contributions: $180,000

- Value at 8% annual return: $679,700

Sporadic saver:

- Saves $1,000/month for 15 years (same total contribution)

- Then stops

- Total contributions: $180,000

- Value at 8% annual return: $339,850

The consistent saver accumulates $339,850 more despite identical total contributions because compound growth had more time to work[8].

The implementation formula:

- Calculate after-tax monthly income

- Multiply by target savings percentage (start with 20%)

- Set up an automatic transfer for that amount

- Budget remaining income across all other categories

- Increase savings rate by 1% whenever income increases

Realistic starting point:

If 20% feels impossible, start with 5% and commit to increasing by 1% every quarter. This gradual approach builds the habit while allowing spending adjustments to occur incrementally.

Year 1: 5% savings rate

Year 2: 9% savings rate

Year 3: 13% savings rate

Year 4: 17% savings rate

Year 5: 20%+ savings rate

Takeaway: The ideal savings rate balances current needs with future security. Start with any percentage, automate the process, and increase systematically. Consistency over decades matters more than perfection in any single month.

Common Budgeting and Saving Mistakes Beginners Make

Understanding typical failures helps avoid them. The following mistakes account for most budget abandonment within the first three months.

Mistake 1: Creating Unrealistic Categories

New budgeters often underestimate expenses or create overly optimistic spending limits. A grocery budget of $200 when historical spending averages $500 guarantees failure.

The solution:

Track actual spending for 30-60 days before creating budget limits. Use real data, not aspirational goals, as the baseline. Then reduce categories by 5-10% rather than 50%.

Example:

- Actual dining out spending: $400/month

- Unrealistic budget: $100/month (75% reduction)

- Realistic budget: $300/month (25% reduction)

- Sustainable approach: Reduce by $50 every two months until reaching the desired level

Mistake 2: Forgetting Irregular Expenses

Annual, quarterly, or sporadic expenses (car registration, insurance premiums, holiday gifts, home maintenance) destroy budgets when they appear unexpectedly.

The solution:

Create an irregular expense fund by calculating annual irregular costs and dividing by 12:

Example calculation:

- Car insurance (annual): $1,200

- Car registration: $150

- Home insurance: $800

- Holiday gifts: $600

- Home maintenance: $1,000

- Professional dues: $250

- Total annual: $4,000

- Monthly allocation: $333

Set aside $333 monthly in a separate account. When irregular expenses occur, pay them from this fund rather than disrupting the regular budget.

Mistake 3: No Buffer Categories

Rigid budgets with zero flexibility create failure when reality doesn’t match predictions perfectly. A $300 grocery budget with no buffer means a $320 grocery month feels like failure.

The solution:

Include a “miscellaneous” or “buffer” category of 5-10% of the budget. This absorbs small overages without derailing the entire plan.

Buffer allocation:

- Monthly budget: $4,000

- Buffer category: $200 (5%)

- Purpose: Cover small overages in variable categories

If the buffer goes unused, transfer it to savings at month-end. If it gets depleted regularly, the budget needs adjustment.

Mistake 4: Quitting After One Bad Month

A single month of overspending doesn’t indicate budget failure—it indicates learning data. Most people abandon budgets after the first imperfect month rather than adjusting and continuing.

The solution:

Expect imperfection. Budget success is measured over 12 months, not 30 days. After a difficult month:

- Analyze what went wrong (unexpected expense, miscalculated category, impulse spending)

- Adjust budget categories based on new information

- Implement one specific improvement (not ten)

- Continue the process

Progress mindset:

Month 1: Over budget by $400 (learning phase)

Month 2: Over budget by $250 (improvement)

Month 3: Over budget by $100 (continued progress)

Month 4: On budget (success)

This trajectory is normal.

Mistake 5: Not Accounting for Income Variability

Budgets based on best-case income fail when income dips. Commission workers, freelancers, and seasonal employees need different approaches.

The solution:

Budget using the lowest expected monthly income from the past 12 months. When income exceeds this baseline, allocate the excess to savings or debt rather than increasing spending.

Variable income example:

- Monthly income range: $3,000-$6,000

- Budget baseline: $3,000

- Months earning $6,000: Extra $3,000 goes to savings/debt

- Months earning $3,000: Budget works without stress

Mistake 6: Ignoring Small Subscriptions

$10 monthly subscriptions feel insignificant individually but compound into budget-destroying amounts collectively.

The math:

- Streaming service 1: $15

- Streaming service 2: $12

- Music subscription: $10

- Cloud storage: $10

- App subscriptions: $20

- Gym membership (unused): $40

- Total: $107/month or $1,284/year

The solution:

Audit all subscriptions quarterly. Cancel anything unused in the past 30 days. Rotate subscriptions rather than maintaining all simultaneously.

Mistake 7: Not Separating Savings from Checking

Money in checking accounts feels spendable. Savings goals stored in the same account as spending money rarely survive until the end of the month.

The solution:

Maintain separate accounts:

- Checking: Monthly expenses only

- High-yield savings: Emergency fund

- Separate savings: Specific goals (down payment, vacation, etc.)

- Investment accounts: Long-term wealth building

Physical and mental separation protects savings from impulsive spending.

Takeaway: Budget failure stems from unrealistic expectations, incomplete planning, and abandonment after initial imperfection. Success comes from using real data, building in flexibility, and treating the first three months as a learning period rather than a pass/fail test.

Budgeting Tools and Calculators That Help

Technology simplifies budgeting and saving by automating tracking, calculations, and progress monitoring. The following tools reduce friction and increase adherence.

Spreadsheet-based budgeting:

Custom spreadsheets provide complete control and flexibility. Create category rows, income columns, and formulas that calculate totals and remaining funds automatically.

Advantages:

- Free (Google Sheets, Excel)

- Completely customizable

- No privacy concerns

- Works offline

Disadvantages:

- Requires manual transaction entry

- No automatic bank syncing

- Steeper learning curve

Budgeting apps:

Apps like YNAB (You Need A Budget), Mint, and EveryDollar connect to bank accounts and automatically categorize transactions.

Advantages:

- Automatic transaction import

- Real-time spending tracking

- Mobile accessibility

- Visual progress reports

Disadvantages:

- Monthly fees (some)

- Privacy considerations

- Requires bank account linking

- Learning curve for features

Calculator tools:

Purpose-built calculators remove mathematical complexity from planning decisions.

Use a budget calculator to quickly determine optimal category allocations based on income and goals. This eliminates guesswork and provides data-driven starting points.

A savings calculator shows exactly how monthly contributions grow over time with compound interest, making long-term goals tangible and motivating.

Envelope budgeting apps:

Digital versions of the envelope method (Goodbudget, Mvelopes) provide envelope-style budgeting without physical cash.

Advantages:

- Envelope method benefits without cash inconvenience.

- Works for online purchases

- Visual spending limits

- Partner account sharing

Choosing the right tool:

The best tool is the one you’ll use consistently. Consider:

- Tech comfort level: Spreadsheets for advanced users, apps for simplicity

- Privacy preferences: Spreadsheets for maximum privacy, apps for convenience

- Budget complexity: Simple budgets work in basic apps; complex situations benefit from spreadsheets

- Cost sensitivity: Free tools (spreadsheets, Mint) versus paid options (YNAB)

Implementation approach:

- Start with one tool (don’t use multiple simultaneously)

- Commit to 90 days of consistent use

- Evaluate effectiveness

- Switch only if the current tool clearly isn’t working

Takeaway: Tools reduce friction but don’t replace the fundamental requirement of intentional decision-making. Choose based on personal preferences, then focus on consistent use rather than perfect tool selection.

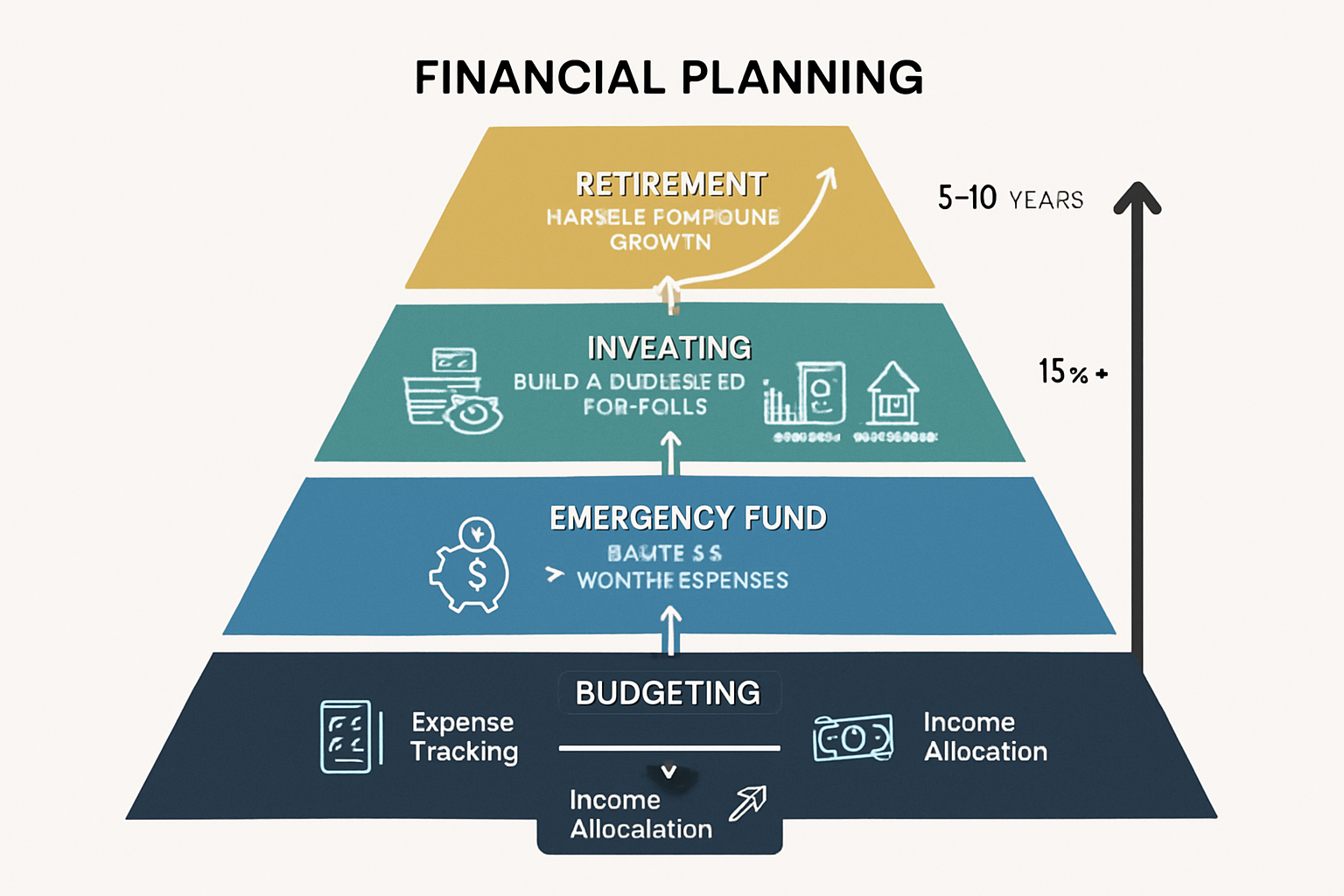

How Budgeting and Saving Fit Into Your Bigger Financial Plan

Budgeting and saving represent the foundation of wealth building, not the destination. Understanding how these practices connect to larger financial goals creates motivation and context.

The financial progression:

Stage 1: Budget and cash flow control

- Create a spending plan

- Track all expenses

- Eliminate wasteful spending

- Establish baseline financial awareness

Stage 2: Emergency fund

- Save 3-6 months of expenses

- Create a financial buffer

- Eliminate dependence on debt for unexpected expenses

- Build confidence and security

Stage 3: Debt elimination

- Pay off high-interest debt

- Free up cash flow

- Reduce financial stress

- Redirect debt payments to investing

Stage 4: Investment and wealth building

- Contribute to retirement accounts

- Build a taxable investment portfolio

- Harness compound growth

- Create passive income streams

Stage 5: Advanced optimization

- Tax strategy refinement

- Estate planning

- Wealth preservation

- Legacy building

The mathematical connection:

Each stage enables the next through freed cash flow and accumulated capital:

Example progression:

Year 1-2: Budget creates $500/month surplus → Emergency fund

Year 3-4: Emergency fund complete, $500/month → Debt elimination

Year 5+: Debt eliminated, $500/month + former debt payment of $400/month = $900/month → Investing

That $900 monthly invested at 8% annual returns for 25 years becomes $779,432[9].

Why budgeting and saving are step one:

Without controlled spending, no surplus exists to fund later stages. Without emergency savings, unexpected expenses force reliance on debt, preventing progress toward investing.

The sequence matters mathematically:

Correct sequence:

Budget → Save → Eliminate debt → Invest = Wealth

Incorrect sequence:

Invest without an emergency fund → Unexpected expense → Sell investments at a loss or take debt = Wealth destruction

The compound effect of early action:

Starting budgeting and saving at age 25 versus 35 creates dramatically different outcomes:

Age 25 start:

- 40 years of compound growth

- $500/month at 8% = $1,745,503 at age 65

Age 35 start:

- 30 years of compound growth

- $500/month at 8% = $745,179 at age 65

- Difference: $1,000,324 (57% less wealth)

Integration with broader goals:

Budgeting and saving support every financial goal:

- Homeownership: Saving creates a down payment, and budgeting ensures mortgage affordability

- Career flexibility: An Emergency fund allows job changes, and budgeting reduces income requirements

- Retirement security: Saving funds in retirement accounts, accounting maximizes contribution capacity

- Education funding: Systematic saving builds 529 accounts, and budgeting prevents student loans

- Entrepreneurship: Savings provide startup capital, and budgeting extends the runway

Takeaway: Budgeting and saving are the foundation that makes every other financial goal possible. Master these fundamentals first, then build the wealth-creation strategies that follow.

Budgeting and Saving Action Plan: Your Next Steps

Knowledge without implementation creates no results. The following action plan transforms information into financial progress.

Week 1: Assessment and Baseline

Day 1-2: Track current spending

- Record every expense for 48 hours

- Note amounts and categories

- Identify spending patterns

Day 3-4: Gather financial data

- Collect bank statements (past 3 months)

- List all income sources

- Document all recurring expenses

- Calculate total debt and minimum payments

Day 5-7: Calculate baseline metrics

- Average monthly income

- Average monthly spending by category

- Current savings rate

- Net worth (assets minus liabilities)

Week 2: Budget Creation

Day 8-9: Choose a budgeting method

- Review methods (50/30/20, zero-based, envelope)

- Select one based on income pattern and preferences

- Commit to a 90-day trial

Day 10-12: Create first budget

- List all income sources

- Assign every dollar to categories

- Include the irregular expense fund

- Add 5% buffer category

- Ensure savings allocation (minimum 10%, target 20%)

Day 13-14: Set up accounts and automation

- Open a high-yield savings account if needed

- Set up an automatic savings transfer on payday

- Create separate accounts for different savings goals

- Configure the budgeting tool or spreadsheet

Week 3: Implementation

Day 15-21: Execute budget

- Follow budget categories

- Track all spending

- Use the budgeting tool daily

- Resist impulse purchases

- Note challenges and adjustments needed

Week 4: Review and Adjust

Day 22-24: Analyze results

- Compare actual spending to the budget

- Identify categories that need adjustment

- Calculate the actual savings rate

- Review what worked and what didn’t

Day 25-28: Refine budget

- Adjust unrealistic categories

- Add forgotten expense categories

- Modify allocation percentages

- Set specific goals for month 2

Month 2-3: Optimization

Weeks 5-12:

- Continue tracking and budgeting

- Increase savings rate by 1-2%

- Reduce one spending category by 10%

- Build an emergency fund of $1,000 minimum

- Review and adjust monthly

Month 4+: Advanced Implementation

Ongoing actions:

- Maintain budget consistency

- Increase the savings rate quarterly

- Build an emergency fund for 3-6 months’ expenses

- Begin investing once the emergency fund is complete

- Review and optimize annually

Progress milestones:

Month 1: Budget created and followed (even if imperfectly)

Month 3: Budget adherence 80%+, savings automated

Month 6: Emergency fund at $1,000+, spending optimized

Month 12: Emergency fund at 1-2 months’ expenses, 15%+ savings rate

Year 2: Emergency fund complete, investing begun, 20%+ savings rate

Accountability systems:

- Schedule monthly budget review (same day each month)

- Track progress in a spreadsheet or an app

- Share goals with an accountability partner

- Celebrate milestones (without expensive rewards)

- Join the financial community for support

Common obstacles and solutions:

Obstacle: “I don’t make enough to save.”

Solution: Start with 2% savings rate, reduce one expense category by 10%, and increase the rate as income grows

Obstacle: “Unexpected expenses keep destroying my budget.”

Solution: Build an irregular expense fund, increase the buffer category, and adjust expectations for the first 90 days

Obstacle: “I can’t stick to the budget.”

Solution: Increase flexibility in want categories, ensure needs are adequately funded, and use cash for problem categories

Obstacle: “My income varies too much.”

Solution: Budget using the lowest monthly income, save excess during high-income months.

Takeaway: Implementation beats perfect planning. Start with week 1 actions today rather than waiting for the perfect moment. Progress compounds like investment returns—small, consistent actions create substantial results over time.

💰 Interactive Budget Calculator

Calculate your ideal budget allocation using proven methods

Your Budget Breakdown

📊 Insights & Recommendations

- Your savings rate of 20% aligns with financial planning best practices

- At this rate, you’ll save $12,000 annually toward emergency fund and investments

- Consider increasing savings by 1% each quarter as income grows

- Automate your $1,000 monthly savings transfer on payday

Conclusion: Building Wealth Through Budgeting and Saving Discipline

Budgeting and saving transform financial chaos into systematic wealth building. The evidence is clear: controlling spending through intentional budgeting and prioritizing saving through automation creates the foundation for every financial goal that follows.

The math behind money is straightforward—income minus controlled expenses equals wealth-building capacity. Without budgeting, expenses expand unconsciously to consume all available income. Without systematic saving, temporary income becomes permanent consumption rather than lasting wealth.

Key principles for implementation:

Start immediately with imperfect action. Waiting for the perfect budget, ideal income level, or complete understanding delays the compound growth that time creates. A 15% savings rate started today produces better outcomes than a 25% rate started in five years.

Automate to remove willpower from the equation. Automatic transfers to savings accounts on payday ensure consistency regardless of motivation, stress, or competing priorities. Automation transforms saving from an active decision into a passive system.

Treat budgeting as a learning process, not a pass/fail test. The first three months provide data about actual spending patterns, category accuracy, and necessary adjustments. Expect imperfection and use it as information rather than evidence of failure.

Connect present actions to future outcomes. Every dollar saved and invested today becomes multiple dollars in the future through compound growth. A $500 monthly savings habit started at age 25 becomes $1,745,503 by age 65 at 8% returns—this tangible outcome motivates present discipline.

Build the complete financial system. Budgeting and saving enable emergency funds, which enable debt elimination, which enables investing, which enables wealth building. Each stage depends on the previous one. Start with stage one today.

Your next action steps:

- This week: Track all spending for 7 days to establish baseline data

- Next week: Create the first budget using the 50/30/20 method or zero-based approach

- This month: Set up automatic savings transfer for 10-20% of income

- Next quarter: Review progress, adjust categories, increase savings rate by 1%

- This year: Build an emergency fund to $1,000 minimum, then 3-6 months’ expenses

The difference between financial stress and financial security isn’t income level—it’s the systematic application of budgeting and saving principles. These practices work at $30,000 annual income and $300,000 annual income because the math behind money doesn’t change.

Wealth building begins with controlling what you can control: spending decisions, savings habits, and intentional allocation of every dollar earned. Master these fundamentals, then build the investing and optimization strategies that compound your discipline into lasting wealth.

Start today. Track one day of spending. Create one budget category. Set up one automatic transfer. Small actions compound into life-changing results when sustained over time.

The math behind money rewards those who understand that budgeting and saving aren’t restrictions—they’re the foundation of financial freedom.

References

[1] Federal Reserve. (2024). Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households. Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2024-economic-well-being-of-us-households.htm

[2] American Psychological Association. (2024). Stress in America Survey. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress

[3] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2024). Credit Card Interest Calculator. Retrieved from https://www.consumerfinance.gov/

[4] Compound interest calculations based on standard financial formulas using 8% average annual return, monthly compounding.

[5] Bankrate. (2024). Annual Emergency Savings Report. Retrieved from https://www.bankrate.com/banking/savings/emergency-savings-report/

[6] Calculations based on compound interest formula: FV = PMT × [((1 + r)^n – 1) / r], where r = monthly interest rate, n = number of months.

[7] Thaler, R. H. (1999). Mental Accounting Matters. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12(3), 183-206.

[8] Time-value of money calculations demonstrating the impact of consistent contributions versus sporadic, larger contributions.

[9] Future value calculations based on monthly contributions, 8% annual return, and monthly compounding over specified time periods.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that explains the math behind money with precision and authority. With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based investing principles, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable guidance for beginner to intermediate investors. His work focuses on helping readers understand how wealth, investing, and risk management truly work through numbers, logic, and verifiable evidence rather than hype or speculation.

Educational Disclaimer

This article provides educational information about budgeting and saving principles and should not be construed as personalized financial advice. Financial decisions depend on individual circumstances, goals, risk tolerance, and complete financial situations that cannot be fully assessed through general content.

Budgeting methods, savings rates, and allocation percentages discussed represent general guidelines based on financial planning research and may not be appropriate for all individuals. Readers should evaluate their specific situations and consider consulting qualified financial professionals before making significant financial decisions.

Historical investment returns referenced in examples represent averages and do not guarantee future performance. Actual returns vary based on market conditions, investment selection, timing, fees, and numerous other factors.

The Rich Guy Math and Max Fonji do not provide personalized investment advice, tax guidance, or legal counsel. This content serves educational purposes only and aims to improve financial literacy through clear explanations of evidence-based principles.

Readers are responsible for their own financial decisions and should conduct thorough research and seek professional guidance appropriate to their circumstances.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much should I save each month if I’m just starting out?

Start with at least 10% of your after-tax income, even if that feels small. The goal is building the habit of consistent saving rather than hitting a perfect percentage immediately.

Once the 10% habit is established—typically within 3 to 6 months—gradually increase your savings by 1% every quarter until reaching 20% or more.

For example, someone earning $3,000 per month would start by saving $300, then increase to $330, $360, and so on. Automating transfers on payday is critical so saving happens before spending.

What’s the difference between a budget and tracking expenses?

Tracking expenses records what you already spent, making it backward-looking and descriptive. Budgeting plans where your money will go before spending occurs, making it forward-looking and prescriptive.

Tracking provides awareness of past behavior, while budgeting drives future behavior. The most effective approach combines both—use tracking data to build a realistic budget, then follow the budget to guide spending.

Should I save money or pay off debt first?

Start by building a small emergency fund of $1,000. Then focus on paying off high-interest debt like credit cards and payday loans. Afterward, expand your emergency fund to cover 3–6 months of expenses.

This sequence prevents new debt when emergencies arise. Paying off 18% interest debt provides a guaranteed 18% return, but without an emergency buffer, you risk falling back into debt.

How do I budget with irregular income?

Base your budget on the lowest monthly income you earned in the past 12 months. Cover all essential expenses within that amount.

When income exceeds this baseline, direct the excess toward savings, debt repayment, or sinking funds instead of increasing spending.

For example, if income ranges from $3,000 to $7,000 per month, build your budget around $3,000 and treat the remainder as bonus income assigned to specific goals.

What percentage of income should go to housing?

Financial planners generally recommend keeping housing costs below 30% of gross income, with 25% offering greater flexibility.

Someone earning $5,000 per month should aim to keep total housing costs between $1,250 and $1,500. Exceeding this range often forces cuts to savings and slows long-term wealth building.

How can I save money when I’m living paycheck to paycheck?

Track every expense for 30 days to uncover hidden spending. Many people find $100–$300 per month leaking through subscriptions, convenience purchases, or impulse buys.

Next, automate a small savings transfer—$25 to $50—on payday. Reduce discretionary spending by 10–20% using the needs versus wants framework.

Finally, increase income through side work, selling unused items, or negotiating higher pay. Combining reduced spending with increased income creates savings capacity even on tight budgets.

What’s the best budgeting app or tool?

The best budgeting tool is the one you’ll use consistently. YNAB excels at zero-based budgeting but charges a monthly fee. Mint offers free tracking with automation but less control. Spreadsheets provide full customization but require manual effort.

Commit to one tool for at least 90 days before switching. Most budgeting failures result from inconsistency, not poor tool choice.

How long does it take to see results from budgeting?

Most people feel reduced financial stress within 2–4 weeks as clarity replaces uncertainty. Tangible financial results—higher savings or lower debt—typically appear within 2–3 months.

Significant wealth-building progress becomes visible within 12–24 months of consistent budgeting. The benefits follow a predictable pattern: psychological relief first, behavioral change next, and financial growth over time.