Credit and debt are two sides of the same financial coin—one represents your ability to borrow money, while the other represents the balance you owe. Understanding how credit works and mastering debt management separates those who build wealth from those who remain financially stuck.

Most people use credit without understanding the math behind it. They carry balances, miss the connection between utilization and scores, and confuse credit reports with credit scores. This knowledge gap costs them thousands in interest and decades of financial progress.

This guide explains the mechanics of credit, the reality of debt, and the strategic frameworks that actually work for getting out of debt. Every concept includes the cause-and-effect relationships that drive financial outcomes, backed by data and evidence-based strategies.

Key Takeaways

- Credit is borrowed money you promise to repay—not free money- and debt is the actual balance you owe to lenders.

- Payment history accounts for 35% of your credit score—making it the single most important factor in credit scoring models.

- Credit utilization above 30% damages your score—even if you pay on time, high utilization signals risk to lenders.

- Debt avalanche saves more money than debt snowball—but behavioral psychology often makes snowball more effective for completion.

- Debt consolidation only helps if you stop creating new debt—otherwise, you’re just moving balances without solving the root problem.

What Is Credit and Debt?

Credit is money a lender allows you to borrow with the agreement that you’ll repay it, usually with interest. Debt is the actual amount you owe after borrowing that money.

Credit itself is neither good nor bad—it’s a financial tool. A mortgage that builds home equity can be strategic. A credit card balance carrying 24% interest on discretionary purchases is destructive. The difference lies in the interest rate, the cash flow impact, and what you purchased with borrowed money.

Debt becomes dangerous when the cost of borrowing exceeds the value received. This happens through high interest rates, extended repayment periods, or purchasing depreciating assets with borrowed money. A $30,000 car loan at 8% interest loses value the moment you drive off the lot, while you pay thousands in interest—that’s value destruction, not wealth building.

The math is simple: if you borrow at 18% but your investments return 7%, you’re losing 11% annually on that capital. This negative spread compounds against you, making debt repayment the highest guaranteed return available in your financial plan.

Understanding this relationship changes how you view every borrowing decision. Credit provides access to capital. Debt represents the cost of that access. Managing both strategically determines your financial trajectory.

🔗 Learn more: what is credit

🔗 Foundation concept: Personal Finance Basics

How Credit Works Behind the Scenes

Credit operates through a three-party system: lenders (banks, credit card companies), credit bureaus (Experian, TransUnion, Equifax), and you (the borrower).

When you apply for credit, lenders assess risk by requesting your credit report from one or more bureaus. These reports contain your borrowing history, payment patterns, current balances, and public records. Lenders use this data to calculate the probability you’ll repay borrowed money.

Why lenders care about risk: Every loan carries default risk—the chance you won’t repay. Lenders price this risk through interest rates. Lower-risk borrowers receive lower rates. Higher-risk borrowers pay premium rates or get denied entirely. This risk-based pricing protects lenders’ capital and determines your borrowing costs.

Credit bureaus collect data from creditors monthly. When you make a payment, miss a payment, or open a new account, creditors report this information. Bureaus compile these reports and sell them to lenders, insurance companies, landlords, and employers.

Why paying on time matters more than income: Payment history demonstrates reliability better than income level. Someone earning $50,000 who always pays on time presents less risk than someone earning $150,000 with missed payments. Consistency predicts future behavior more accurately than current income.

The system rewards predictability. Lenders profit from borrowers who repay reliably, not from defaults. This creates an incentive structure where demonstrating consistent repayment behavior unlocks better terms, lower rates, and higher credit limits.

Understanding this system reveals the leverage points: payment timing, utilization management, and account longevity all signal lower risk to lenders, which translates to better financial terms throughout your life.

🔗 Deep dive: how credit works

🔗 External authority: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau – Credit Reports and Scores

Credit Scores Explained

What a Credit Score Is

A credit score is a three-digit number (typically 300-850) that quantifies your creditworthiness based on mathematical models analyzing your credit report data. The most common model is the FICO Score, used in 90% of lending decisions.[1]

Credit scores translate complex borrowing behavior into a single metric that lenders can quickly assess. Higher scores indicate lower default probability. Lower scores signal higher risk and result in declined applications or higher interest rates.

The score itself is a prediction model. FICO analyzes millions of credit files to identify patterns that correlate with repayment behavior. These patterns become weighted factors in the scoring algorithm, creating a standardized risk assessment tool.

Different scoring models exist (FICO, VantageScore, industry-specific models), but all use similar underlying principles: payment history, debt levels, credit age, account mix, and recent activity. The specific weights vary, but the core factors remain consistent across models.

Understanding that your score is a risk prediction—not a judgment of character—changes how you approach credit management. It’s a mathematical output based on specific inputs. Change the inputs, and the output changes predictably.

🔗 Complete guide: credit score explained

Credit Score Ranges (What’s Good vs Bad)

FICO scores range from 300 to 850, divided into categories that determine lending terms:

| Score Range | Rating | Lending Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 800-850 | Exceptional | Best rates, highest approval odds, premium rewards cards |

| 740-799 | Very Good | Excellent rates, strong approval odds, most premium products |

| 670-739 | Good | Competitive rates, good approval odds, standard products |

| 580-669 | Fair | Higher rates, moderate approval odds, limited product selection |

| 300-579 | Poor | Highest rates or denial, difficult approvals, secured products only |

The 740 threshold matters most. Most lenders offer their best rates to borrowers above 740. The difference between 740 and 800 rarely affects your interest rate, but the gap between 680 and 740 can cost thousands in additional interest.

For example, on a $300,000 30-year mortgage, the difference between a 6.5% rate (fair credit) and a 5.8% rate (very good credit) equals approximately $47,000 in additional interest paid over the loan term. That’s the real cost of a lower credit score.

Score ranges also determine approval for rental applications, insurance rates, and even employment in certain industries. The financial impact extends beyond borrowing costs into multiple life areas.

Building from fair to good credit (580 to 670) typically takes 12-18 months of consistent positive behavior. Moving from good to very good (670 to 740) requires another 12-24 months. The timeline extends as you approach exceptional ranges because negative items age off your report slowly.

🔗 Detailed breakdown: credit score ranges

What Affects Your Credit Score

Five factors determine your credit score, each weighted differently in the FICO model:

1. Payment History (35% of score)

This tracks whether you pay bills on time. Even one 30-day late payment can drop your score 60-110 points, depending on your starting score. The impact decreases over time, but late payments remain on your report for seven years.

Cause and effect: Lenders view payment history as the strongest predictor of future behavior. If you’ve missed payments before, statistical models predict a higher likelihood of future misses. This single factor outweighs all others combined.

2. Credit Utilization (30% of score)

Utilization measures how much available credit you’re using. It’s calculated per card and across all cards. Using more than 30% of available credit signals financial stress to scoring models.

The math: If you have a $10,000 credit limit and carry a $4,000 balance, your utilization is 40%—above the optimal threshold. Reducing that balance to $2,000 (20% utilization) would improve your score, even without changing any other factor.

3. Length of Credit History (15% of score)

This measures the average age of all your accounts and the age of your oldest account. A longer history provides more data points for risk assessment, which generally improves scores.

Why it matters: A 10-year credit history demonstrates sustained borrowing behavior. A 6-month history offers limited predictive value. Time builds trust in the model.

4. Credit Mix (10% of score)

Having different types of credit (revolving credit cards, installment loans, mortgages) demonstrates you can manage various repayment structures. This diversity slightly improves scores.

Reality check: Don’t take out loans just to improve the mix. The 10% weight doesn’t justify creating unnecessary debt. Natural diversification through needed borrowing is sufficient.

5. New Credit Inquiries (10% of score)

Each hard inquiry (credit application) can temporarily lower your score 5-10 points. Multiple inquiries in short periods signal credit-seeking behavior, which correlates with financial stress in statistical models.

The exception: Rate shopping for mortgages or auto loans within 14-45 days (depending on scoring model version) counts as a single inquiry. This allows comparison shopping without penalty.

These five factors interact dynamically. Improving utilization while maintaining a perfect payment history creates compounding positive effects. Conversely, missing payments while maxing out cards creates compounding negative impacts.

🔗 Factor analysis: what affects your credit score

Credit Reports vs Credit Scores

Your credit report is the raw data—a detailed document listing every credit account, payment history, balance, credit limit, and public record associated with your identity. Your credit score is a number calculated from that data.

Think of the report as your financial transcript and the score as your GPA. The transcript contains all the details. The GPA summarizes performance in a single number.

What’s on a credit report:

- Personal information (name, addresses, Social Security number)

- Credit accounts (cards, loans, mortgages) with a payment history

- Credit inquiries (who checked your credit and when)

- Public records (bankruptcies, tax liens, civil judgments)

- Collections accounts (debts sent to collection agencies)

Who creates credit reports: The three major credit bureaus (Experian, TransUnion, Equifax) each maintain separate reports. Information can vary between bureaus because not all creditors report to all three bureaus.

How errors happen: Creditors sometimes report incorrect information—wrong balances, accounts belonging to someone else, or payments marked late when they were on time. Identity theft can also create fraudulent accounts on your report.

The correction process: You have the right to dispute errors directly with credit bureaus. They must investigate within 30 days and correct verified errors. This can immediately improve your score if negative items are removed.

Checking your credit report regularly (at least annually) catches errors before they damage your score during important applications. Federal law guarantees one free report per bureau annually through AnnualCreditReport.com.[2]

Your credit score updates whenever your report data changes. Paying down balances, adding on-time payments, or removing errors all trigger score recalculations. The score is dynamic, not static.

Understanding this distinction prevents confusion when you see different scores from different sources. Each bureau’s data may differ slightly, producing different scores even using the same scoring model.

Good Debt vs Bad Debt

The “good debt versus bad debt” framework oversimplifies, but the underlying principle matters: debt that builds wealth or increases earning capacity differs from debt that funds consumption.

Good debt characteristics:

- Interest rate below expected investment returns: If you borrow at 3.5% but invest at 7%, the spread works in your favor

- Purchases appreciating or income-producing assets: Real estate that gains value, education that increases earnings

- Manageable cash flow impact: Monthly payments don’t strain your budget or prevent saving

Example: A $200,000 mortgage at 3.5% on a property appreciating 4% annually creates positive leverage. You’re borrowing at 3.5% to own an asset, gaining 4%, plus building equity through principal payments. The math works.

Bad debt characteristics:

- Interest rate exceeds investment returns: Credit card debt at 18-24% while savings earn 4% creates a negative 14-20% spread

- Purchases of depreciating assets: Cars, electronics, and clothing lose value immediately

- Strains cash flow: Payments prevent saving, investing, or building emergency funds

Example: A $5,000 credit card balance at 22% interest costs $1,100 annually just in interest if you only make minimum payments. That’s $1,100 that could compound in investments instead of enriching credit card companies.

The risk level matters: Even “good debt” becomes destructive if taken excessively. A mortgage you can’t afford leads to foreclosure regardless of the interest rate. Student loans for degrees with poor job prospects create a burden without an income increase.

Cash flow impact determines sustainability: Debt becomes problematic when payments consume too much monthly income. The 28/36 rule suggests housing costs shouldn’t exceed 28% of gross income, and total debt payments shouldn’t exceed 36%. Exceeding these thresholds increases default risk.

The reality: most consumer debt is bad debt. Credit cards, personal loans, and auto loans typically fund consumption at rates exceeding investment returns. Strategic debt use requires discipline that most borrowers don’t demonstrate.

🔗 Framework guide: good debt vs bad debt

Common Types of Consumer Debt

Understanding debt categories helps prioritize repayment and recognize patterns in your borrowing behavior.

Credit Cards

Revolving debt with variable interest rates typically ranging from 15-29%. Minimum payments barely cover interest, extending repayment for decades if you only pay minimums. The average American household with credit card debt carries $6,270 in balances.[3]

Why they’re dangerous: The revolving structure and high rates create perpetual debt cycles. Paying minimums on $6,000 at 20% APR takes 15+ years and costs $7,000+ in interest.

Personal Loans

Unsecured installment loans with fixed rates (typically 6-36%) and fixed repayment terms (2-7 years). Used for debt consolidation, large purchases, or emergencies.

The catch: Rates depend heavily on credit scores. Fair credit borrowers might pay 20-30%, making these expensive despite being “installment” loans. Always compare the total interest cost, not just the monthly payment.

Auto Loans

Secured installment loans (the car is collateral) with rates typically 4-15% depending on credit and vehicle age. Average new car loan: $40,000+ with 5-7 year terms.

The problem: Cars depreciate 20% the first year and 15% annually thereafter. You’re paying interest on a declining asset, often owing more than the car’s worth (underwater/negative equity) for years.

Student Loans

Federal or private loans fund education with rates typically 4-12%. Federal loans offer income-driven repayment and forgiveness options. Private loans function like standard installment loans.

The complexity: Student loan debt requires different strategies than consumer debt. Federal loans have unique benefits (forbearance, forgiveness programs) that make aggressive payoff sometimes suboptimal compared to investing. Private student loans lack these benefits and should be treated like any high-interest debt.

Each debt type requires specific strategies. Credit cards demand aggressive payoff due to high rates. Student loans may benefit from income-driven plans. Auto loans might warrant refinancing. Treating all debt identically ignores the mathematical differences in cost and strategic value.

How to Get Out of Debt Strategically

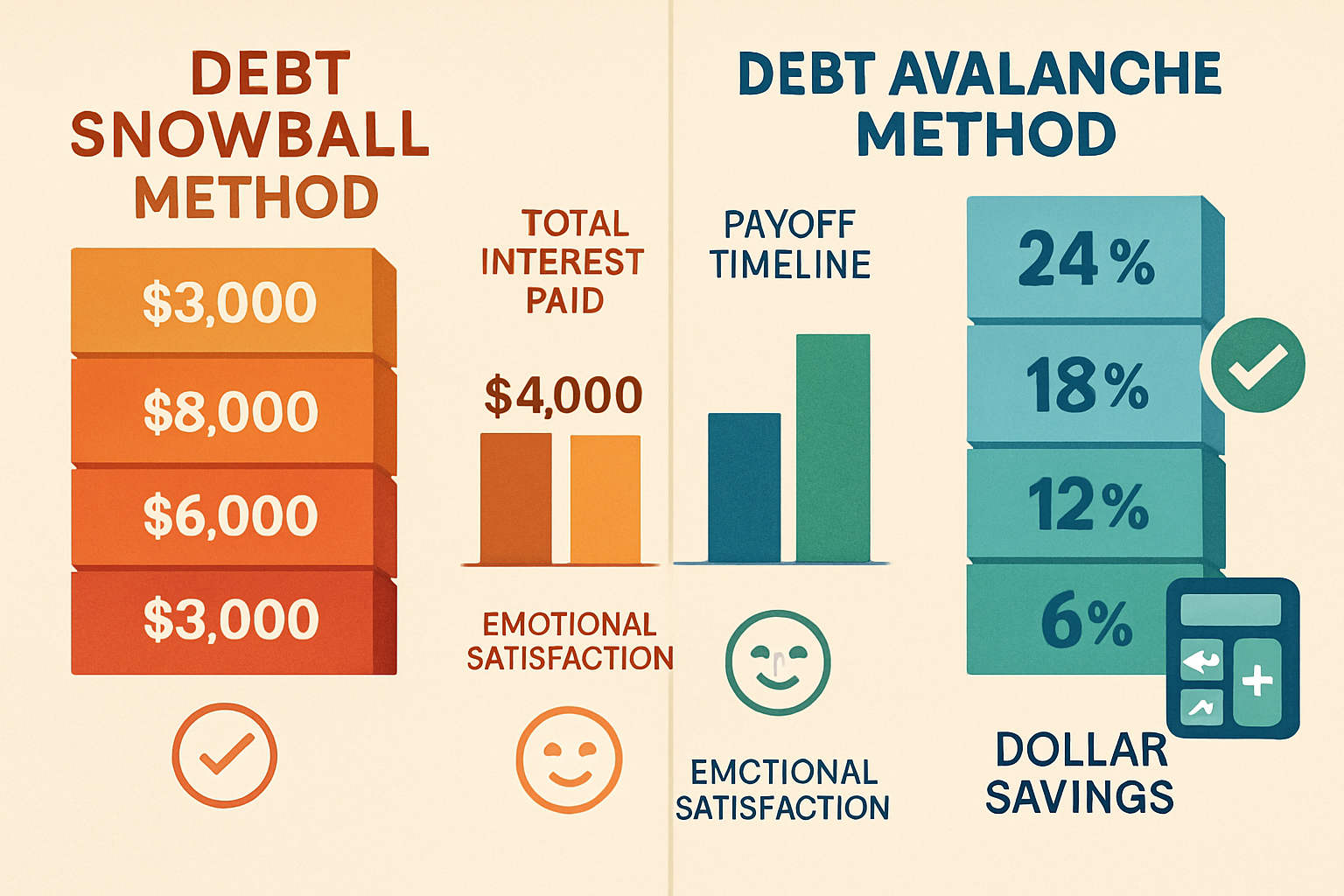

Debt elimination requires a systematic approach, not just motivation. Two primary strategies dominate: debt snowball and debt avalanche. Both work—they just optimize for different outcomes.

Debt Snowball Method

The approach: List all debts from smallest balance to largest, regardless of interest rate. Pay minimums on everything except the smallest debt. Attack the smallest debt with all extra money until it’s gone. Then roll that payment to the next smallest debt.

Why it works behaviorally: Eliminating small debts quickly creates psychological wins. These victories build momentum and motivation. You see accounts disappearing, which reinforces the behavior.

The math trade-off: You’ll pay more total interest than the avalanche method because you’re not prioritizing high-rate debt. But if the behavioral boost keeps you consistent, the psychological benefit outweighs the mathematical cost.

Best for: People who need motivation and quick wins. Those who’ve failed at debt payoff before. Borrowers with similar interest rates across debts (where the math difference is minimal).

Example:

- Credit Card A: $500 at 18%

- Credit Card B: $2,000 at 22%

- Personal Loan: $5,000 at 12%

Snowball attacks the $500 first, then $2,000, then $5,000—regardless of the 22% rate on Card B.

🔗 Complete method: debt snowball method

Debt Avalanche Method

The approach: List all debts from the highest interest rate to the lowest. Pay minimums on everything except the highest-rate debt. Attack the highest-rate debt with all extra money until it’s gone. Then roll that payment to the next highest rate.

Why it works mathematically: You minimize total interest paid. Every dollar goes toward the most expensive debt first, reducing the compound cost of borrowing faster than any other method.

The behavioral challenge: High-rate debts often have larger balances. Progress feels slower. The first payoff might take months, testing motivation before you see results.

Best for: Mathematically-minded people. Those with significant interest rate spreads (15%+ vs 5%). Borrowers with strong discipline who don’t need quick wins for motivation.

Example (same debts):

- Credit Card B: $2,000 at 22% ← attack first

- Credit Card A: $500 at 18%

- Personal Loan: $5,000 at 12%

Avalanche attacks the 22% debt first, saving hundreds in interest compared to snowball.

🔗 Complete method: debt avalanche method

Which Strategy Works Best?

The mathematical winner: Debt avalanche saves more money. Always. The math is indisputable—the highest rates first minimize interest costs.

The behavioral winner: Debt snowball has higher completion rates. Studies show people using snowball are more likely to become debt-free because motivation matters more than optimization for most people.[4]

The hybrid approach: Start with snowball to build momentum, then switch to avalanche once you’ve eliminated 2-3 small debts. This captures psychological wins early while optimizing mathematically later.

The real answer: The best method is the one you’ll actually complete. A mathematically suboptimal plan executed consistently beats an optimal plan abandoned halfway through.

Calculate your specific situation: If your highest-rate debt is also your smallest balance, the methods converge—do that one first, regardless. If interest rates are similar (all within 3-4% of each other), snowball makes sense since the math difference is minimal.

The strategy matters less than the execution. Both methods require finding extra money to accelerate payoff through budget cuts, income increases, or both. The method just determines the order. The intensity determines the timeline.

Debt Consolidation — When It Helps and When It Hurts

Debt consolidation means combining multiple debts into a single new loan, typically with a lower interest rate or lower monthly payment. This can be done through personal loans, balance transfer credit cards, or home equity loans.

What consolidation actually does:

- Simplifies multiple payments into one payment

- Potentially lowers interest rate (if you qualify for better terms)

- May reduce the monthly payment (by extending the repayment period)

- Can improve credit score (by reducing credit card utilization)

When consolidation helps:

You secure a significantly lower interest rate (5%+ reduction)

You stop creating new debt (the root behavior changes)

You maintain or shorten the repayment timeline (don’t extend from 3 years to 7 years)

The fees don’t negate savings (origination fees, balance transfer fees stay under 3%)

Example of effective consolidation: You have $15,000 across three credit cards averaging 21% interest. You qualify for a personal loan at 9% with a 3-year term. Your monthly payment drops from $550 to $477, and you save $6,000+ in interest while paying off debt faster.

When consolidation hurts:

You continue using the paid-off credit cards (creating new debt on top of the consolidation loan)

You extend the timeline excessively (turning 3 years of payments into 7 years)

You use home equity for unsecured debt (converting credit card debt into secured debt risks your home)

The new rate isn’t significantly better (consolidating 18% debt into 15% debt barely helps)

The common mistake: People consolidate, feel relief from lower payments, then charge up the credit cards again. Now they have the consolidation loan plus new credit card debt—worse than before. This pattern often repeats until they have multiple consolidation loans and maxed cards.

The harsh reality: Consolidation treats the symptom (high payments, high rates) but not the disease (overspending, lack of budget discipline). Without addressing the root cause, consolidation just delays the inevitable.

Who should avoid consolidation:

- Those without a budget or spending plan

- People who’ve consolidated before and reaccumulated debt

- Anyone considering home equity loans for credit card debt (too risky)

- Borrowers who can’t qualify for rates significantly lower than their current debt

Consolidation is a tool, not a solution. It works when combined with behavioral change and strategic planning. It fails when used as a band-aid for deeper financial problems.

🔗 Detailed analysis: debt consolidation explained

Credit Mistakes That Keep People Stuck in Debt

Common credit behaviors sabotage financial progress while appearing harmless or even strategic. These mistakes compound over time, keeping people in debt cycles for years.

Mistake 1: Carrying Balances for Rewards

The myth: “I carry a balance to build credit and earn rewards.”

The reality: You don’t need to carry a balance to build credit. Paying in full each month builds credit just as effectively while avoiding interest charges. The 2% cash back doesn’t offset 18% interest—you’re losing 16% on every dollar.

The math: Earning $20 in rewards while paying $150 in interest is a net loss of $130. That’s not strategy; it’s expensive confusion.

Mistake 2: Maxing Cards Repeatedly

The damage: High utilization (above 30%) damages your credit score even if you pay on time. Maxing out cards signals financial stress to scoring models, dropping your score 50-100 points.

The cycle: Lower score → higher rates on new credit → more expensive debt → harder to pay down → repeat.

The fix: Keep utilization under 30% on each card and across all cards. Pay down balances before statement closing dates to report lower utilization.

Mistake 3: Closing Old Accounts

Why people do it: “I paid off this card, so I’ll close it to avoid temptation.”

The consequence: Closing accounts reduces your total available credit, which increases utilization on remaining cards. It also reduces your average account age, hurting the length of your credit history.

The better approach: Keep old cards open with small recurring charges (Netflix, Spotify) set to autopay. This maintains the credit limit and account age while preventing closure due to inactivity.

Mistake 4: Ignoring Utilization Timing

The misunderstanding: “I pay my card in full every month, so utilization doesn’t matter.”

The reality: Bureaus report your balance on the statement closing date, not the payment due date. If your statement closes with a $4,000 balance on a $5,000 limit (80% utilization), that’s what reports—even if you pay in full before the due date.

The solution: Pay down balances before the statement closing date. This report shows lower utilization while still earning rewards on purchases.

Mistake 5: Applying for Multiple Cards in Short Periods

The appeal: Sign-up bonuses and rewards seem valuable.

The cost: Each application creates a hard inquiry. Multiple inquiries in short periods (outside of rate shopping windows) signal credit-seeking behavior, dropping your score and making you appear risky to lenders.

The guideline: Space credit applications at least 3-6 months apart unless rate shopping for mortgages or auto loans (which have special inquiry windows).

Mistake 6: Only Making Minimum Payments

The trap: Minimum payments feel manageable, but they’re designed to maximize lender profit, not help you become debt-free.

The reality: On a $5,000 balance at 20% APR, minimum payments (typically 2-3% of balance) take 15+ years to pay off and cost $7,000+ in interest. You pay $12,000 total for $5,000 borrowed.

The solution: Always pay more than the minimum. Even an extra $50/month cuts years off the repayment timeline and thousands in interest.

These mistakes share a common thread: short-term thinking that ignores long-term costs. Each decision seems small in isolation, but compounds into significant financial damage over time.

Credit and Debt Tools That Can Help

Strategic tools accelerate progress by providing clarity, automation, and accountability. These resources turn abstract goals into concrete action plans.

Debt Payoff Calculators

These tools show exactly how long debt elimination takes based on payment amounts and methods. Input your debts, interest rates, and available payment amounts to see:

- Payoff timeline for snowball vs avalanche

- Total interest paid under different scenarios

- Monthly payment needed to achieve specific payoff dates

Value: Seeing that increasing your payment from $500 to $650 monthly cuts 3 years off your timeline and saves $8,000 in interest makes the sacrifice tangible and motivating.

🔗 Calculate your timeline: debt payoff calculator

Credit Utilization Calculators

These tools help optimize your utilization ratio by showing how different payment amounts affect your reported utilization.

Use case: You have three cards with different balances and limits. The calculator shows which cards to pay down first to maximize score improvement per dollar spent.

🔗 Optimize your utilization: credit utilization calculator

Budget Tracking Apps

Apps like Mint, YNAB (You Need A Budget), or EveryDollar connect to your accounts and track spending automatically. They reveal where money goes and identify cuts that free up cash for debt payoff.

The insight: Most people underestimate discretionary spending by 30-40%. Tracking reveals the actual numbers, making budget adjustments data-driven rather than guesswork.

Credit Monitoring Services

Free services (Credit Karma, Experian, many credit card issuers) provide regular score updates and report monitoring. They alert you to changes, new accounts, or potential fraud.

The benefit: Catching errors or fraud early prevents score damage. Monitoring progress as you pay down debt and improve utilization motivates visible improvement.

Automatic Payment Systems

Setting up autopay for minimum payments prevents late payments (which devastate scores). You can still make additional manual payments while ensuring the minimum always posts on time.

The protection: Even if you forget or face a chaotic month, autopay prevents 35% of your score controlled by payment history from taking a hit.

Debt Tracking Spreadsheets

Simple spreadsheets listing all debts, balances, rates, and minimum payments create visibility. Update monthly as balances decrease to visualize progress.

The psychology: Watching the total debt number decrease monthly reinforces positive behavior. Seeing accounts disappear creates momentum.

Tools don’t replace discipline, but they reduce friction and increase awareness. They transform vague intentions (“I should pay down debt”) into specific actions (“I need to pay $650 to Card B by the 15th to hit my 18-month payoff goal”).

How Credit and Debt Fit Into Your Bigger Financial Plan

Credit and debt management isn’t the end goal—it’s a prerequisite for wealth building. Understanding where it fits in your overall financial progression prevents misallocated effort.

The financial progression sequence:

- Budget and cash flow control → You can’t manage debt without knowing where money goes

- Debt elimination (high-interest) → Paying 18-24% interest destroys wealth faster than almost any investment builds it

- Emergency fund (3-6 months expenses) → Prevents new debt when unexpected expenses arise

- Employer retirement match → Free money (100% return) beats debt payoff in most cases

- Remaining debt payoff → Eliminate moderate-rate debt (6-12%) before aggressive investing

- Investing for wealth building → Compound growth in diversified portfolios builds long-term wealth

- Advanced strategies → Tax optimization, real estate, business ownership

Why debt mastery comes before wealth building:

The math is straightforward. Carrying $10,000 at 20% interest costs $2,000 annually. To break even through investing, you’d need to earn $2,000 on $10,000—a 20% return. Sustained 20% returns are unrealistic for most investors.

Therefore, paying off 20% debt is equivalent to earning a guaranteed 20% return. No investment offers guaranteed 20% returns. Debt payoff is the highest guaranteed return available.

The exception: Low-rate debt (3-5% mortgages, federal student loans) may warrant slower payoff while you invest in tax-advantaged accounts. The expected 7-10% investment returns exceed the 3-5% debt cost, creating positive arbitrage.

Budget → debt control → saving → investing creates the foundation for compound growth. Skipping debt elimination to invest while carrying high-interest debt is mathematically backwards. The negative compound effect of debt outweighs the positive compound effect of investing at those rates.

Credit’s role in wealth building:

Good credit unlocks lower rates on strategic debt (mortgages, business loans), which can accelerate wealth building. A 740+ credit score might save $50,000-$100,000 in interest over a 30-year mortgage compared to a 640 score.

Building credit strategically—using cards responsibly, paying on time, maintaining low utilization—creates financial optionality. You can access capital at favorable terms when opportunities arise.

The integration: View credit and debt as the foundation of your financial house. You can’t build wealth on a crumbling foundation of high-interest debt and poor credit. But once the foundation is solid, wealth building accelerates through investing, asset accumulation, and compound growth.

This perspective prevents the trap of optimizing credit scores while ignoring investing, or aggressively investing while ignoring destructive debt. The sequence matters. Master credit and eliminate high-cost debt first, then shift focus to wealth accumulation.

Interactive Debt Payoff Comparison Tool

💳 Debt Snowball vs Avalanche Calculator

Compare both methods to see which saves you more money and time

Enter Your Debts

❄️ Debt Snowball

⛰️ Debt Avalanche

💡 Avalanche Method Saves You:

📋 Snowball Payoff Order (Smallest to Largest):

📋 Avalanche Payoff Order (Highest Rate to Lowest):

Conclusion

Credit and debt represent two sides of financial leverage—one measures your borrowing capacity, the other measures what you owe. Mastering both creates the foundation for wealth building, while mismanaging either keeps you financially stuck regardless of income.

The key insights:

Credit works through a risk-assessment system where payment history (35% of score) and utilization (30% of score) dominate scoring models. Understanding this system reveals the leverage points: pay on time, keep utilization under 30%, maintain old accounts, and limit new inquiries.

Debt becomes destructive when the cost exceeds the value received. High-interest consumer debt at 18-24% destroys wealth faster than almost any investment builds it, making aggressive payoff the highest guaranteed return available in your financial plan.

Strategic debt elimination requires choosing a method and executing consistently. Debt avalanche minimizes interest costs mathematically. Debt snowball maximizes behavioral completion rates. The best method is the one you’ll actually finish.

Consolidation only works when paired with behavioral change. Moving balances to lower rates helps if you stop creating new debt. It hurts if you charge up paid-off cards, creating new debt on top of consolidation loans.

Credit and debt mastery precedes wealth building. You can’t build sustainable wealth on a foundation of high-interest debt and poor credit. The sequence matters: budget control → debt elimination → emergency savings → investing.

Next steps:

- Check your credit report at AnnualCreditReport.com for errors

- Calculate your current utilization across all cards and pay down high balances

- List all debts with balances, rates, and minimums

- Choose snowball or avalanche based on your psychology and math

- Set up autopay for minimums to protect payment history

- Find $100-500 extra monthly through budget cuts or income increases

- Track progress monthly to maintain motivation

The math behind money is clear: eliminate high-cost debt, build strong credit, then redirect freed cash flow toward wealth-building investments. This sequence creates compound positive effects that accelerate financial progress exponentially.

Understanding credit and debt mechanics transforms them from mysterious forces into manageable tools. You now have the frameworks, the cause-and-effect relationships, and the strategic approaches that actually work. Execution is what separates knowledge from results.

Disclaimer

This article provides educational information about credit and debt management for general knowledge purposes. It does not constitute financial advice, credit counseling, or debt management services.

Credit and debt situations vary significantly based on individual circumstances, credit history, income, expenses, and financial goals. Strategies that work for one person may not be appropriate for another.

Before making significant financial decisions regarding credit or debt:

- Consult with qualified financial advisors, credit counselors, or debt management professionals

- Review your specific credit reports and scores from all three bureaus

- Calculate your personal debt-to-income ratio and budget capacity

- Consider your risk tolerance and financial timeline

- Understand all terms, fees, and consequences of credit products or debt strategies

Credit scoring models, lending criteria, interest rates, and financial regulations change over time. Information presented reflects general principles and data available as of 2025, but may not reflect the most current specific rates, rules, or product offerings.

The Rich Guy Math and its contributors are not liable for financial decisions made based on this content. All credit and debt management strategies carry risks and potential consequences that should be carefully evaluated in your specific context.

For personalized guidance, work with licensed financial professionals who can assess your complete financial situation and provide tailored recommendations.

About the Author

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that explains the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and risk management.

With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based education, Max breaks down complex financial concepts into clear, actionable frameworks that empower readers to make informed decisions about credit, debt, investing, and wealth accumulation.

The Rich Guy Math provides comprehensive guides on personal finance fundamentals, credit management, debt elimination strategies, investing principles, and valuation methods—all grounded in data, logic, and proven mathematical relationships.

Max’s approach combines analytical precision with educational clarity, helping readers understand not just what to do with money, but why specific strategies work and how to apply them to their unique financial situations.

Connect with more evidence-based financial education at The Rich Guy Math.

References

[1] FICO. “What is a FICO Score?” myFICO. https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/whats-in-your-credit-score

[2] Federal Trade Commission. “Free Credit Reports.” Consumer Information. https://consumer.ftc.gov/articles/free-credit-reports

[3] Federal Reserve. “Consumer Credit – G.19.” Federal Reserve Statistical Release. https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/current/

[4] Gal, David, and McShane, Blakeley. “Can Small Victories Help Win the War? Evidence from Consumer Debt Management.” Journal of Marketing Research, 2012. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1509/jmr.10.0487

Frequently Asked Questions About Credit and Debt

Can you build credit without going into debt?

Yes. You can build credit without carrying long-term debt by paying balances in full each month. Using a credit card for small, planned purchases and paying it off on time builds positive payment history without interest costs.

Is carrying a balance good for your credit score?

No. Carrying a balance does not improve your credit score and usually hurts it. Credit scores reward on-time payments and low credit utilization, not interest payments.

How fast can you realistically improve your credit score?

Small improvements can happen within 30–60 days, especially by lowering credit utilization and making on-time payments. Larger improvements typically take several months of consistent behavior.

Should I pay off debt or save money first?

In most cases, it’s best to do both. Build a small emergency fund first to avoid new debt, then aggressively pay down high-interest debt while continuing to save modestly.

Does checking my credit score hurt my credit?

No. Checking your own credit score is a soft inquiry and does not affect your credit. Only lender-initiated hard inquiries can temporarily impact your score.