Every dollar invested today carries a hidden question: What will this be worth tomorrow?

In 2025, investors face more choices than ever: stocks, bonds, ETFs, real estate, and crypto. Yet most people can’t accurately calculate what their investments will actually return over time. They guess. They hope. They compare account balances without understanding the math behind the growth.

An Investment Return Calculator removes the guesswork. It transforms abstract financial concepts into concrete numbers, showing exactly how money grows through compound interest, dividend reinvestment, and time. Whether planning for retirement, comparing mutual funds, or evaluating a stock purchase, understanding investment returns is the foundation of wealth building.

This guide explains the math behind investment returns, demonstrates how to calculate ROI accurately, and reveals why even small differences in return rates create massive wealth gaps over decades.

Key Takeaways

- Investment return calculators quantify how initial capital grows over time using compound interest formulas and return rate assumptions

- Compound returns dramatically outperform simple returns due to exponential growth—the math behind long-term wealth creation

- Annualized return (CAGR) provides the most accurate performance comparison across different time periods and investment types

- Total return includes both price appreciation and income (dividends, interest), giving a complete performance picture

- Common calculation mistakes—ignoring fees, forgetting inflation, and timing errors- can distort returns by 2-4% annually, costing hundreds of thousands over decades

What Is Investment Return? (Plain-English Definition)

Investment return measures how much money an investment gains or loses over a specific period.

At its core, the question is: Did this investment make money or lose money?

The basic concept: If $1,000 grows to $1,100 in one year, the investment generated a $100 gain, or a 10% return. If it drops to $900, the investment loses $100, producing a -10% return.

Investment return encompasses two distinct components:

Capital appreciation: The increase (or decrease) in an asset’s price. A stock purchased at $50 that rises to $55 generates $5 in capital appreciation.

Income: Dividends from stocks, interest from bonds, and rent from real estate. A stock paying $2 in annual dividends adds income return on top of any price change.

Total return combines both elements, providing the complete performance picture. This distinction matters because some investments prioritize growth (such as tech stocks), while others emphasize income (including dividend aristocrats and bonds).

Why Return Measurement Matters

Without accurate return calculation, investors cannot:

- Compare different investment options objectively

- Determine if returns justify the risk taken

- Assess whether portfolio performance meets financial goals

- Make evidence-based allocation decisions

Return measurement transforms subjective feelings (“I think my portfolio is doing well”) into objective data (“My portfolio returned 8.3% annually over five years, outperforming the benchmark by 1.2%”).

How the Investment Return Calculator Works

An Investment Return Calculator uses mathematical formulas to project investment growth based on four primary inputs:

1. Initial Investment (Principal): The starting capital amount invested.

2. Return Rate: The expected annual percentage gain (or loss).

3. Time Period: Investment duration, typically measured in years.

4. Additional Contributions: Optional regular deposits (monthly, quarterly, annually).

The calculator applies these inputs to compound interest formulas, generating projections for future value, total gains, and effective returns.

The Calculation Process

Step 1: Determine the compounding frequency. Returns compound annually, quarterly, monthly, or daily. Higher frequency increases total returns because gains generate their own gains more often.

Step 2: Apply the compound interest formula to calculate future value:

FV = PV × (1 + r)^n

Where:

- FV = Future Value

- PV = Present Value (initial investment)

- r = return rate per period

- n = number of compounding periods

Step 3: Calculate total return as the percentage gain from initial investment to final value:

Total Return = [(FV – PV) / PV] × 100

Step 4: Compute annualized return (CAGR) to standardize performance across different time periods:

CAGR = [(FV / PV)^(1/n)] – 1

This process reveals not just the ending balance, but the growth trajectory, allowing investors to visualize how wealth accumulates over time through compound interest.

What the Calculator Shows

A comprehensive Investment Return Calculator displays:

- Future account value at the end of the investment period

- Total dollar gain (ending value minus initial investment)

- Total return percentage (overall gain as a percentage)

- Annualized return (average yearly growth rate)

- Year-by-year breakdown showing balance growth

- Impact of additional contributions on outcomes

These outputs transform abstract return rates into tangible wealth projections, making the invisible math of money visible and actionable.

Investment Return Formula (With Example)

The fundamental investment return formula calculates the percentage gain or loss:

Return = [(Ending Value – Beginning Value) / Beginning Value] × 100

This simple formula provides the foundation for all return calculations.

Basic Return Example

Scenario: An investor purchases 100 shares of stock at $50 per share ($5,000 total investment). One year later, the stock trades at $58 per share ($5,800 total value).

Calculation:

- Beginning Value: $5,000

- Ending Value: $5,800

- Return = [($5,800 – $5,000) / $5,000] × 100

- Return = [$800 / $5,000] × 100

- Return = 16%

The investment generated a 16% return over one year.

Total Return Formula (Including Income)

Most investments generate both capital appreciation and income. The complete return formula incorporates dividends, interest, or other distributions:

Total Return = [(Ending Value – Beginning Value + Income) / Beginning Value] × 100

Total Return Example

Scenario: The same stock investment, but the company paid $200 in dividends during the year.

Calculation:

- Beginning Value: $5,000

- Ending Value: $5,800

- Income (Dividends): $200

- Total Return = [($5,800 – $5,000 + $200) / $5,000] × 100

- Total Return = [$1,000 / $5,000] × 100

- Total Return = 20%

Including dividends, the actual return was 20%, not 16%. This 4% difference demonstrates why dividend investing strategies can significantly boost total returns, especially in lower-growth environments.

Multi-Year Return Formula

For investments held across multiple years, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) provides the most accurate performance metric:

CAGR = [(Ending Value / Beginning Value)^(1 / Number of Years)] – 1

CAGR Example

Scenario: An investor places $10,000 in a mutual fund. After 5 years, the account grows to $16,105.

Calculation:

- Beginning Value: $10,000

- Ending Value: $16,105

- Number of Years: 5

- CAGR = [($16,105 / $10,000)^(1/5)] – 1

- CAGR = [1.6105^0.2] – 1

- CAGR = 1.1000 – 1

- CAGR = 10% per year

The investment averaged a 10% annual return over five years. This annualized return metric enables direct comparison with other investments regardless of time period differences.

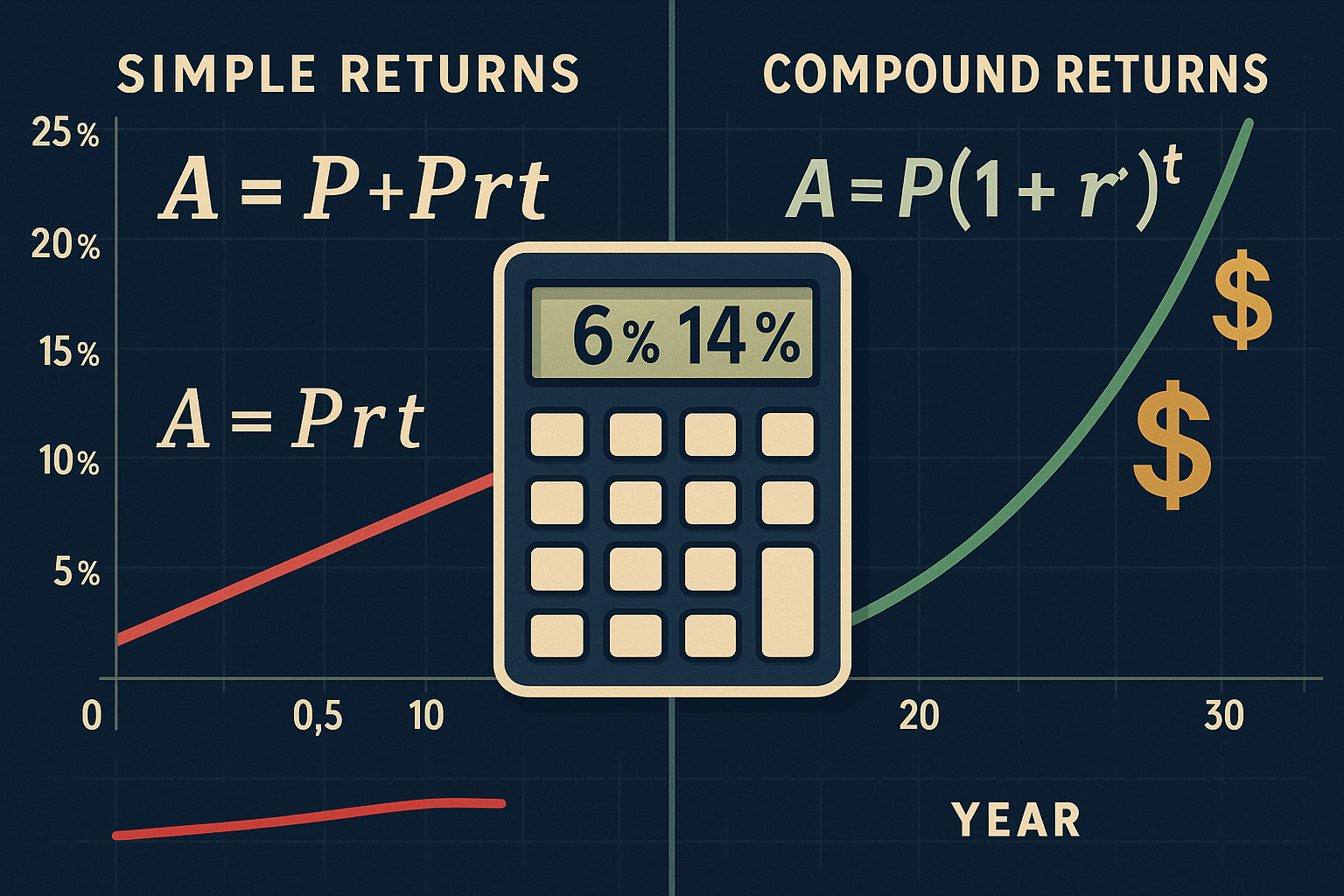

Compound vs Simple Returns

The difference between compound and simple returns represents one of the most powerful concepts in finance, and one of the least understood.

Simple Interest

Simple interest calculates returns only on the original principal, never on accumulated gains.

Formula: Simple Interest = Principal × Rate × Time

Example: $10,000 invested at 8% simple interest for 10 years:

- Year 1: $10,000 × 0.08 = $800 gain → $10,800 total

- Year 2: $10,000 × 0.08 = $800 gain → $11,600 total

- Year 3: $10,000 × 0.08 = $800 gain → $12,400 total

- …

- Year 10: $10,000 × 0.08 = $800 gain → $18,000 total

Each year generates exactly $800 in interest. The growth is linear, a straight line on a graph.

Compound Interest

Compound interest calculates returns on both the original principal and all accumulated gains. Each period’s returns generate their own returns in subsequent periods.

Formula: FV = PV × (1 + r)^n

Same Example with Compounding: $10,000 invested at 8% compound interest for 10 years:

- Year 1: $10,000 × 1.08 = $10,800

- Year 2: $10,800 × 1.08 = $11,664

- Year 3: $11,664 × 1.08 = $12,597

- …

- Year 10: $21,589

The compound investment generates $3,589 more than simple interest, a 20% increase in total wealth from the same return rate and time period.

The Exponential Difference

The gap between simple and compound returns expands exponentially over time:

| Years | Simple (8%) | Compound (8%) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | $14,000 | $14,693 | $693 |

| 10 | $18,000 | $21,589 | $3,589 |

| 20 | $26,000 | $46,610 | $20,610 |

| 30 | $34,000 | $100,627 | $66,627 |

| 40 | $42,000 | $217,245 | $175,245 |

After 40 years, compound returns generate more than 5 times the wealth of simple returns. This mathematical reality explains why early investing and long time horizons create disproportionate wealth advantages.

Why Compound Returns Dominate Real Investing

Nearly all real-world investments use compound returns:

- Stocks: Dividends are reinvested to purchase more shares, which generate more dividends

- Bonds: Interest payments are reinvested to earn additional interest

- Mutual Funds/ETFs: Distributions automatically purchase additional fund shares

- Real Estate: Rental income reinvests into property improvements or additional properties

- Retirement Accounts: All gains remain in the account, compounding tax-deferred

Understanding compound versus simple interest transforms investment strategy from hoping for high returns to maximizing compounding time and frequency.

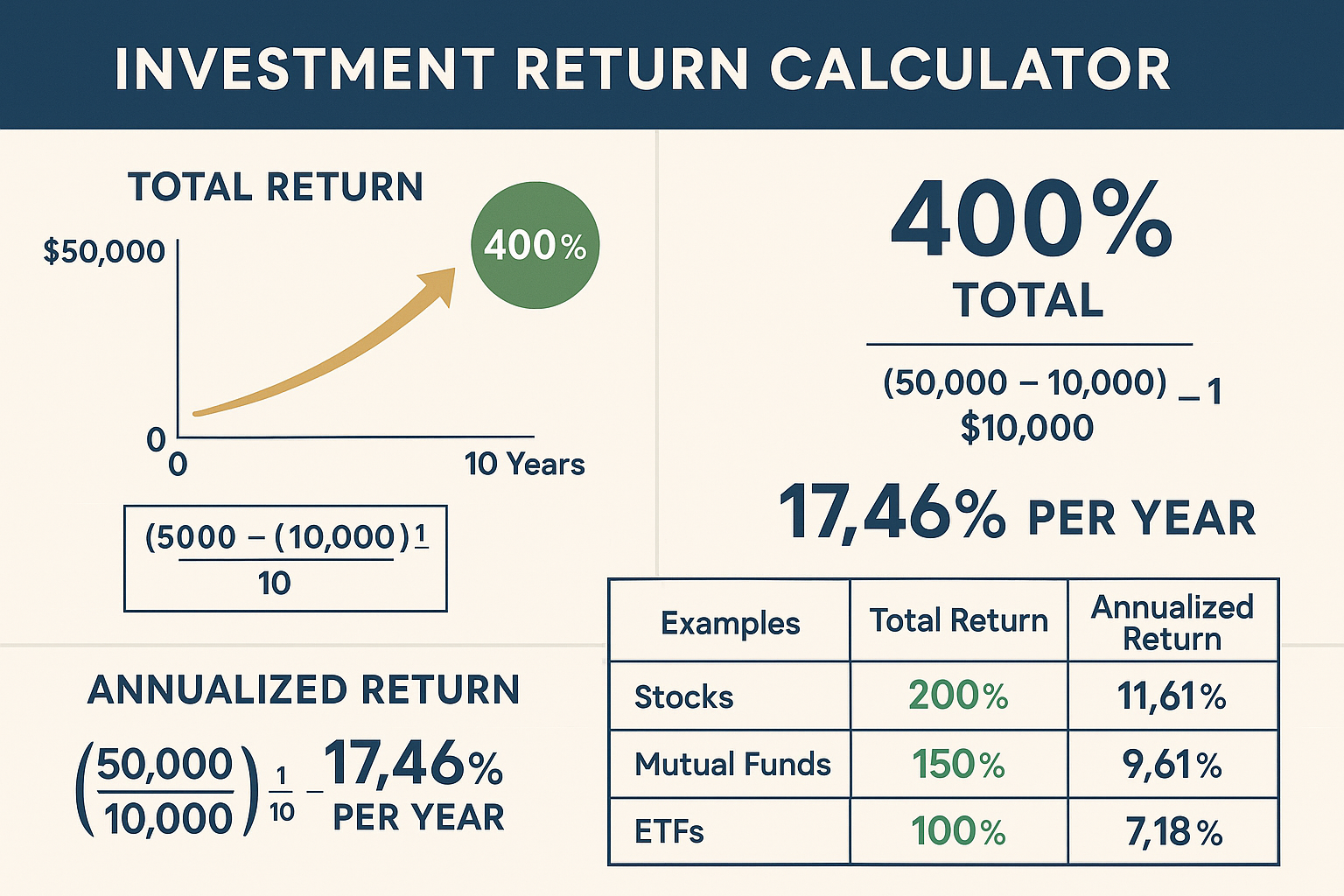

Annualized Return vs Total Return

Investment performance reporting uses two primary metrics: total return and annualized return. Each serves distinct analytical purposes.

Total Return

Total return measures the complete percentage change from beginning to end, regardless of time period.

Formula: Total Return = [(Ending Value – Beginning Value) / Beginning Value] × 100

Example: An investment grows from $10,000 to $15,000 over 3 years.

- Total Return = [($15,000 – $10,000) / $10,000] × 100

- Total Return = 50%

The investment gained 50% over the entire period. Total return answers: How much did this investment grow in total?

Annualized Return (CAGR)

Annualized return converts total return into an average yearly rate, enabling comparison across different time periods.

Formula: CAGR = [(Ending Value / Beginning Value)^(1 / Years)] – 1

Same Example Annualized:

- CAGR = [($15,000 / $10,000)^(1/3)] – 1

- CAGR = [1.5^0.333] – 1

- CAGR = 1.1447 – 1

- CAGR = 14.47% per year

The investment averaged 14.47% annually over three years. Annualized return answers: What was the average yearly growth rate?

Why the Distinction Matters

Comparison accuracy: Total returns cannot be directly compared across different time periods.

Example:

- Investment A: 50% total return over 5 years

- Investment B: 30% total return over 2 years

Which performed better? Total returns don’t reveal the answer.

Annualized comparison:

- Investment A: 8.45% CAGR

- Investment B: 14.02% CAGR

Investment B significantly outperformed on an annual basis despite the lower total return percentage.

When to Use Each Metric

Use Total Return when:

- Evaluating single-period performance (quarterly, annual reports)

- Calculating actual dollar gains for tax or accounting purposes

- Comparing investments held for identical time periods

Use Annualized Return when:

- Comparing investments with different holding periods

- Projecting future performance based on historical averages

- Evaluating fund manager performance against benchmarks

- Making allocation decisions across asset classes

Professional investors and financial advisors primarily use annualized returns (CAGR) for performance analysis because it provides standardized, apples-to-apples comparisons regardless of time period differences.

Example: Stock Investment Return

Real-world investment return calculations incorporate multiple factors: price changes, dividends, fees, and timing.

Scenario Setup

Investment Details:

- Purchase: 200 shares of XYZ Corporation at $75 per share

- Initial Investment: $15,000

- Holding Period: 3 years

- Sale Price: $92 per share

- Annual Dividends: $1.50 per share (paid quarterly)

- Trading Fees: $10 purchase, $10 sale

Year-by-Year Breakdown

Year 1:

- Starting Value: $15,000

- Dividends Received: 200 shares × $1.50 = $300

- Ending Stock Price: $78

- Ending Value: $15,600 (stock) + $300 (dividends) = $15,900

- Year 1 Return: 6.0%

Year 2:

- Starting Value: $15,600 (stock value)

- Dividends Received: $300

- Ending Stock Price: $85

- Ending Value: $17,000 (stock) + $300 (dividends) = $17,300

- Year 2 Return: 10.9%

Year 3:

- Starting Value: $17,000 (stock value)

- Dividends Received: $300

- Ending Stock Price: $92

- Sale Proceeds: $18,400

- Total Dividends Collected: $900 (3 years)

- Final Value: $18,400 + $900 = $19,300

Total Return Calculation

Gross Return:

- Initial Investment: $15,000 + $10 fee = $15,010

- Final Value: $18,400 – $10 fee = $18,390

- Total Dividends: $900

- Net Proceeds: $18,390 + $900 = $19,290

Total Return = [($19,290 – $15,010) / $15,010] × 100 = 28.51%

Annualized Return Calculation

CAGR = [($19,290 / $15,010)^(1/3)] – 1

- CAGR = [1.2851^0.333] – 1

- CAGR = 8.72% per year

Return Components

Breaking down the 28.51% total return:

- Capital Appreciation: ($18,400 – $15,000) / $15,000 = 22.67%

- Dividend Income: $900 / $15,000 = 6.00%

- Trading Costs: -$20 / $15,000 = -0.13%

- Net Total Return: 28.51%

This example demonstrates why total return analysis matters; dividends contributed 6% of the 28.51% gain, representing more than 21% of total returns. Investors focusing only on stock price appreciation would underestimate actual performance significantly.

Example: Mutual Fund Return

Mutual fund return calculations include unique factors: expense ratios, capital gains distributions, and potential sales loads.

Scenario Setup

Investment Details:

- Initial Investment: $25,000

- Fund: Growth & Income Fund

- Holding Period: 5 years

- Expense Ratio: 0.75% annually

- No load (no sales charges)

- Reinvested all distributions

Year-by-Year Performance

| Year | NAV Start | NAV End | Dividends | Capital Gains | Expense Ratio | Net Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $25.00 | $27.50 | $0.50 | $0.25 | 0.75% | $27,438 |

| 2 | $27.50 | $29.00 | $0.55 | $0.30 | 0.75% | $30,211 |

| 3 | $29.00 | $26.75 | $0.52 | $0.15 | 0.75% | $28,456 |

| 4 | $26.75 | $31.25 | $0.60 | $0.40 | 0.75% | $33,847 |

| 5 | $31.25 | $34.50 | $0.65 | $0.50 | 0.75% | $37,892 |

Note: NAV (Net Asset Value) already reflects expense ratio deduction

Total Return Calculation

Final Value: $37,892

Initial Investment: $25,000

Total Return = [($37,892 – $25,000) / $25,000] × 100 = 51.57%

Annualized Return Calculation

CAGR = [($37,892 / $25,000)^(1/5)] – 1

- CAGR = [1.5157^0.2] – 1

- CAGR = 8.67% per year

Impact of Expense Ratio

The 0.75% expense ratio reduced returns by approximately $1,425 over five years. Compared to a hypothetical 0.10% expense ratio fund with identical gross performance:

- 0.75% ER Fund: $37,892 final value (8.67% CAGR)

- 0.10% ER Fund: $39,317 final value (9.45% CAGR)

- Cost Difference: $1,425 (3.76% of total gains)

This comparison reveals why index fund investing with ultra-low expense ratios (0.03-0.10%) has gained popularity; fee differences compound significantly over decades.

Distribution Reinvestment Impact

The fund paid $2.82 per share in total distributions over five years. With automatic reinvestment:

- With Reinvestment: $37,892 final value

- Without Reinvestment: $34,500 final value

- Reinvestment Benefit: $3,392 (9.8% higher ending value)

Dividend reinvestment accelerates compound growth by immediately putting distributions back to work, generating additional returns.

Example: Long-Term Compound Growth

Long-term investing reveals compound interest’s true power and the dramatic impact of seemingly small return rate differences.

Scenario Setup

Three investors each contribute $500 monthly to retirement accounts for 30 years. They invest in different portfolios with varying average annual returns:

- Conservative Portfolio: 6% annual return (bonds, stable dividend stocks)

- Balanced Portfolio: 8% annual return (60/40 stock/bond mix)

- Growth Portfolio: 10% annual return (primarily stocks)

30-Year Projection

Conservative Portfolio (6% return):

- Total Contributions: $180,000

- Final Value: $502,257

- Total Gains: $322,257

- Gains as % of Contributions: 179%

Balanced Portfolio (8% return):

- Total Contributions: $180,000

- Final Value: $745,180

- Total Gains: $565,180

- Gains as % of Contributions: 314%

Growth Portfolio (10% return):

- Total Contributions: $180,000

- Final Value: $1,130,244

- Total Gains: $950,244

- Gains as % of Contributions: 528%

The 2% Difference

The gap between 8% and 10% returns, just 2 percentage points, creates a $385,064 wealth difference over 30 years. This represents:

- 51.7% more wealth in the growth portfolio

- 214% more in total gains

- An additional $12,835 per year in accumulated wealth

This mathematical reality demonstrates why portfolio allocation decisions matter enormously for long-term wealth building, particularly in tax-advantaged retirement accounts where returns compound without annual tax drag.

Time Value Visualization

Breaking down when gains occur reveals compound interest’s exponential nature:

First Decade (Years 1-10):

- Conservative: $82,461 (16% of final value)

- Balanced: $91,524 (12% of final value)

- Growth: $102,310 (9% of final value)

Second Decade (Years 11-20):

- Conservative: $173,042 (34% of final value)

- Balanced: $230,847 (31% of final value)

- Growth: $311,628 (28% of final value)

Third Decade (Years 21-30):

- Conservative: $246,754 (49% of final value)

- Balanced: $422,809 (57% of final value)

- Growth: $716,306 (63% of final value)

Nearly two-thirds of the growth portfolio’s final value accumulated in the last 10 years, despite contributing the same $60,000 in each decade. This phenomenon explains why early investing and a maximum time horizon create disproportionate wealth advantages.

For investors following strategies like the 4% rule for retirement withdrawals, these return differences translate to vastly different sustainable income levels: $20,090/year (conservative) versus $45,210/year (growth), a 125% income difference from the same monthly contribution.

Why Investment Returns Matter

Investment returns determine whether financial goals become reality or remain perpetual aspirations.

Retirement Funding

The math is straightforward: retirement requires accumulating 25-30 times annual expenses (based on the 4% withdrawal rule).

Example: A retiree needs $60,000 annual income.

- Required Portfolio: $1,500,000 (25× multiplier)

Reaching $1,500,000 through $1,000 monthly contributions requires:

- At 6% return: 35.8 years

- At 8% return: 29.6 years

- At 10% return: 25.1 years

The difference between 6% and 10% returns shortens the path to retirement by 10.7 years—more than a decade of working life.

Inflation Protection

Investment returns must exceed inflation to preserve purchasing power. With 3% average inflation:

- 4% return: 1% real return (purchasing power grows slowly)

- 7% return: 4% real return (purchasing power doubles every 18 years)

- 10% return: 7% real return (purchasing power doubles every 10 years)

Returns below inflation rates erode wealth over time, even as nominal account balances increase. A $100,000 portfolio earning 2% annually loses 1% purchasing power yearly with 3% inflation, becoming worth only $74,000 in real terms after 30 years despite showing a $181,000 nominal balance.

Opportunity Cost

Every investment decision carries opportunity cost; the return foregone by not choosing the next-best alternative.

Example: An investor holds $50,000 in a 1% savings account rather than a diversified portfolio returning 8% annually.

10-Year Opportunity Cost:

- Savings Account Value: $55,231

- Investment Portfolio Value: $107,946

- Opportunity Cost: $52,715 (95% of initial capital)

The “safe” choice costs nearly the entire original investment in foregone returns. This calculation doesn’t advocate reckless risk-taking, but illustrates why understanding expected returns across asset classes matters for informed decision-making.

Compound Effect on Financial Independence

Small return improvements compound into massive wealth differences over decades:

$500,000 invested for 20 years:

| Return Rate | Final Value | Total Gain | Gain vs 6% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6% | $1,603,567 | $1,103,567 | Baseline |

| 7% | $1,934,842 | $1,434,842 | +$331,275 |

| 8% | $2,330,477 | $1,830,477 | +$726,910 |

| 9% | $2,802,389 | $2,302,389 | +$1,198,822 |

| 10% | $3,363,750 | $2,863,750 | +$1,760,183 |

Each 1% return improvement generates hundreds of thousands in additional wealth. This mathematical reality explains why portfolio optimization, fee minimization, and tax efficiency matter significantly; each can contribute 0.5-2% in additional annual returns, compounding to six or seven figures over investing lifetimes.

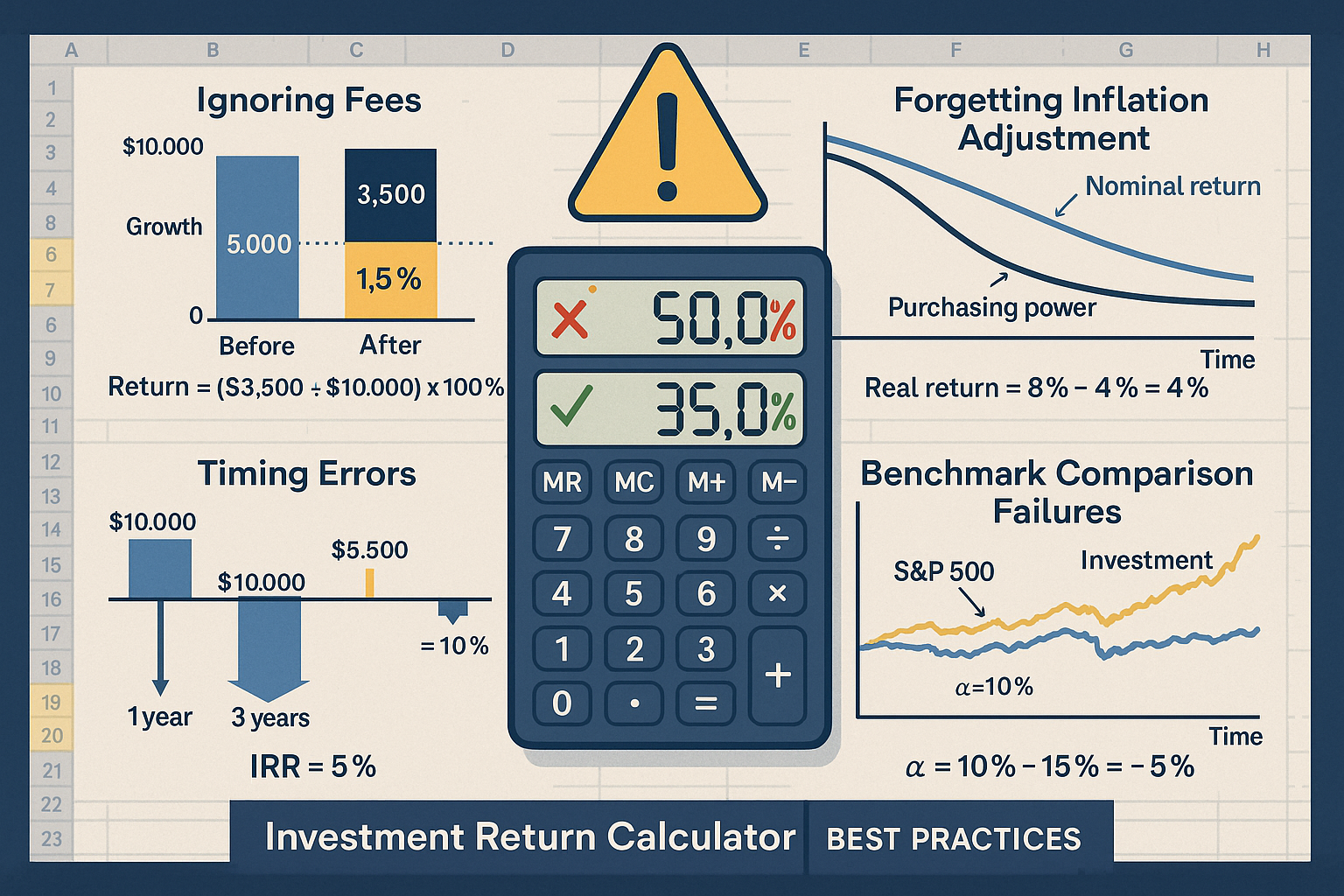

Common Mistakes When Calculating Investment Returns

Accurate return calculation requires avoiding systematic errors that distort performance assessment.

Mistake #1: Ignoring Fees and Expenses

The Error: Calculating returns based on gross performance without deducting fees, commissions, and expense ratios.

The Impact: A fund showing 9% gross returns with a 1.5% expense ratio actually delivers 7.5% net returns to investors.

Over 30 years on $100,000:

- 9% gross (7.5% net): $806,231

- 9% net (no fees): $1,326,768

- Cost of ignoring fees: $520,537

The Fix: Always calculate returns net of all costs. Include:

- Expense ratios (mutual funds, ETFs)

- Advisory fees (robo-advisors, financial advisors)

- Trading commissions

- Bid-ask spreads

- Tax costs (for taxable accounts)

Even “small” 0.5% fee differences compound to 15-20% wealth differences over 30+ years.

Mistake #2: Forgetting Inflation Adjustment

The Error: Evaluating returns in nominal (dollar) terms without adjusting for inflation’s purchasing power erosion.

The Impact: A 6% nominal return with 3% inflation equals only 3% real return, half the apparent performance.

Example: $50,000 growing at 6% nominal for 20 years:

- Nominal Value: $160,357

- Real Value (3% inflation): $88,726

- Purchasing Power: 55% of nominal value

The Fix: Calculate real returns using the formula:

Real Return = [(1 + Nominal Return) / (1 + Inflation Rate)] – 1

For 6% nominal return with 3% inflation:

- Real Return = [1.06 / 1.03] – 1 = 2.91%

Evaluate all long-term investments in real (inflation-adjusted) terms to assess actual wealth creation.

Mistake #3: Incorrect Time Period Calculations

The Error: Miscounting years in multi-year return calculations, especially with mid-year purchases or sales.

Example: An investment purchased on July 1, 2020, and sold on July 1, 2025, spans exactly 5 years, not 6.

The Impact: Using 6 years instead of 5 in CAGR calculations:

- Correct (5 years): 10.0% CAGR

- Incorrect (6 years): 8.45% CAGR

- Error: 1.55 percentage points (15.5% understatement)

The Fix: Calculate exact time periods using:

- Precise dates for partial years

- Day count conventions for bonds

- Actual holding periods, not calendar years

For investments with irregular cash flows, use time-weighted return or internal rate of return (IRR) methodologies rather than simple CAGR.

Mistake #4: Failing to Account for Cash Flows

The Error: Using simple return formulas when additional contributions or withdrawals occurred during the investment period.

Example: An account starts with $10,000, receives a $5,000 contribution mid-year, and ends at $16,000.

Incorrect Calculation:

- Return = [($16,000 – $10,000) / $10,000] × 100 = 60%

Correct Calculation (Money-Weighted Return):

- Must account for the timing of the $5,000 contribution

- Actual return ≈ 12-15% depending on contribution timing

The Fix: Use money-weighted return (internal rate of return) for portfolios with irregular cash flows. Most investment platforms calculate this automatically as “personal rate of return.”

Mistake #5: Comparing Apples to Oranges

The Error: Comparing investments with different risk profiles, time horizons, or tax treatments without adjustment.

Example: Comparing a 7% municipal bond return (tax-free) to an 8% corporate bond return (taxable) for an investor in the 32% tax bracket.

Tax-Equivalent Comparison:

- Municipal Bond: 7% (tax-free)

- Corporate Bond: 8% × (1 – 0.32) = 5.44% after-tax

- Municipal bond actually returns 29% more after taxes

The Fix: Adjust for:

- Tax treatment: Convert to after-tax returns for taxable accounts

- Risk levels: Compare risk-adjusted returns (Sharpe ratio, Sortino ratio)

- Liquidity: Account for liquidity premiums in illiquid investments

- Time horizons: Use annualized returns for different periods

Valid comparisons require standardizing all variables except the specific performance metric being evaluated.

Mistake #6: Overlooking Benchmark Comparison

The Error: Evaluating absolute returns without comparing to relevant market benchmarks.

Example: An actively managed stock fund returns 9% annually over 10 years.

Seems Good Until:

- S&P 500 returned 11% over the same period

- Fund underperformed the benchmark by 2% annually

- Opportunity cost: $143,000 on $100,000 initial investment

The Fix: Always compare investment returns to appropriate benchmarks:

- U.S. stocks: S&P 500, Russell 2000

- International stocks: MSCI EAFE, MSCI Emerging Markets

- Bonds: Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index

- Balanced portfolios: 60/40 stock/bond benchmark

Outperformance matters more than absolute returns. A 6% return during a -5% market year represents excellent performance; a 15% return during a +25% market year represents underperformance.

💰 Investment Return Calculator

Your Investment Results

Conclusion

An Investment Return Calculator transforms abstract financial concepts into concrete wealth projections, revealing the mathematical truth behind money growth.

The fundamental insights are clear:

Compound returns dominate wealth creation. The exponential growth curve separates financially successful individuals from those who struggle, not through income differences, but through understanding how returns compound over time.

Small percentage differences create massive wealth gaps. A 2% annual return advantage compounds to 50-100% more wealth over 30 years. This reality makes portfolio optimization, fee minimization, and tax efficiency crucial for long-term success.

Time matters more than timing. Starting early with moderate returns outperforms starting late with high returns. A 25-year-old investing $500 monthly at 8% accumulates more wealth by age 65 than a 35-year-old investing $1,000 monthly at 10%, despite contributing half as much.

Accurate measurement enables informed decisions. Investors who calculate returns correctly, accounting for fees, taxes, inflation, and cash flows, make better allocation decisions than those relying on rough estimates or marketing materials.

Next Steps

1. Calculate your current investment returns using the formulas and methods outlined above. Determine actual performance net of all fees and expenses.

2. Compare returns to appropriate benchmarks. Assess whether active management, high fees, or suboptimal allocation are costing you wealth.

3. Project future wealth using realistic return assumptions (6-10% for diversified stock portfolios, 3-5% for bonds, 2-4% for cash). Determine whether current savings rates will achieve financial goals.

4. Optimize for compound growth by maximizing time horizon, minimizing fees, implementing tax-efficient strategies, and maintaining consistent contributions through market cycles.

5. Review and adjust annually. Investment returns fluctuate. Regular performance assessment ensures portfolios stay aligned with goals, risk tolerance, and market conditions.

The math behind money rewards those who understand it. An Investment Return Calculator provides the analytical framework to transform financial aspirations into mathematical certainty, one compound period at a time.

For investors seeking to build wealth systematically, understanding investment returns isn’t optional. It’s the foundation upon which every sound financial decision rests.

Disclaimer

This article provides educational information about investment return calculations and financial concepts. It does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice.

Investment returns discussed represent historical averages or hypothetical scenarios. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Actual investment returns vary based on market conditions, asset allocation, fees, taxes, and individual circumstances.

All investment decisions carry risk, including potential loss of principal. Before making investment decisions, consult qualified financial, tax, and legal professionals who understand your specific situation, goals, and risk tolerance.

The calculations, formulas, and examples provided are for educational purposes only. While mathematically accurate, they cannot account for all real-world variables affecting investment performance.

The Rich Guy Math and its contributors are not responsible for investment decisions made based on this content. Always conduct thorough research and seek professional guidance before investing.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform dedicated to explaining the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and risk management.

With expertise in financial analysis and evidence-based investing strategies, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable insights for beginner and intermediate investors. His approach emphasizes understanding cause-and-effect relationships in finance, using data and logic to demystify money management.

Max’s mission is to build financial literacy through precision teaching, helping readers understand not just what works in finance but why it works, backed by numbers, formulas, and empirical evidence.

Through The Rich Guy Math, Max provides comprehensive guides on compound interest, dividend investing, absolute returns, and fundamental financial principles that empower informed decision-making.

References

[1] Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) – Historical S&P 500 Returns: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

[2] Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – Investor Education on Returns: https://www.sec.gov/investor

[3] CFA Institute – Investment Performance Measurement Standards: https://www.cfainstitute.org/

[4] Morningstar – Mutual Fund and ETF Performance Data: https://www.morningstar.com/

[5] Vanguard Research – The Impact of Asset Allocation on Portfolio Returns: https://institutional.vanguard.com/

[6] Federal Reserve – Consumer Price Index and Inflation Data: https://www.federalreserve.gov/

[7] Investopedia – Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) Definition: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/cagr.asp

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a good investment return rate?

A good investment return depends on asset class and risk level. Historically, diversified stock portfolios return 8–10% annually, bonds return 3–5%, and cash equivalents return 1–3%.

A “good” return generally means exceeding inflation by 3–5% while matching your risk tolerance. A 7% real (inflation-adjusted) return doubles purchasing power roughly every 10 years, representing strong long-term performance.

How do I calculate ROI on an investment?

ROI is calculated using the formula:

ROI = [(Current Value − Initial Investment) ÷ Initial Investment] × 100

For accuracy, include all income received (dividends, interest) and subtract all costs (fees, commissions, taxes). For multi-year investments, convert ROI to an annualized return using CAGR for proper comparisons.

What’s the difference between total return and annualized return?

Total return measures the full percentage gain over the entire holding period, such as 50% over five years.

Annualized return (CAGR) converts that gain into an average yearly rate, allowing comparisons across investments with different timelines. For example, a 50% return over 10 years equals about 4.14% annually, while a 30% return over two years equals roughly 14.02% annually.

Should I use simple or compound interest for investment calculations?

Always use compound interest for investment calculations. Real-world investments compound as gains generate additional gains through reinvested dividends, retained capital appreciation, and tax-deferred growth.

Simple interest applies only to limited cases, such as certain bonds held to maturity. Over 30+ years, the difference between simple and compound growth can exceed 100%.

How often should investment returns compound?

Most investments compound daily or monthly. Stocks and mutual funds compound continuously as prices change and dividends reinvest. Bonds typically compound semi-annually.

Higher compounding frequency slightly increases returns. Daily compounding outperforms annual compounding by roughly 0.1–0.3% annually at typical return levels. Monthly compounding provides realistic projections for long-term planning.

What investment return do I need for retirement?

Required returns depend on savings rate, timeline, and income needs. Using the 4% withdrawal rule, retirees need approximately 25× annual expenses saved.

Achieving this typically requires 6–8% real returns over 30–40 years with consistent contributions. Lower returns require higher savings or longer working years.

How do fees affect investment returns?

Fees reduce returns directly and compound negatively over time. A 1% annual fee on a $100,000 portfolio earning 8% costs $1,000 in year one but compounds to more than $28,000 over 30 years.

Expense ratio differences of just 0.5–1% can reduce final retirement wealth by 15–25%. Using low-cost index funds effectively increases returns without added risk.

Can I trust investment return calculators?

Investment calculators provide mathematically accurate projections but cannot predict actual future returns. Markets fluctuate, and real returns vary year to year.

Use calculators for scenario planning with conservative assumptions—such as 6–7% for stocks and 3–4% for bonds—and run multiple scenarios