Financial literacy is the ability to understand and effectively apply financial skills, including budgeting, saving, investing, and debt management, to make informed money decisions that improve long-term outcomes.

Most people never learn how money actually works. Schools teach calculus and chemistry but skip the math behind paychecks, interest rates, and compound growth. As a result, millions of Americans earn good incomes yet struggle with debt, lack emergency savings, and feel confused about investing.

This isn’t about intelligence. It’s about education.

Financial literacy bridges that gap. It transforms money from a source of stress into a tool for building security and freedom. Understanding how financial decisions create ripple effects, both positive and negative, changes everything. The difference between financial stability and chronic struggle often comes down to knowing a handful of core principles and applying them consistently.

This guide breaks down the fundamental concepts that govern how money flows through your life, why certain decisions compound wealth while others erode it, and how to build a financial foundation that works regardless of income level.

Key Takeaways

- Financial literacy is decision quality, not wealth level — understanding how money works matters more than how much you earn.

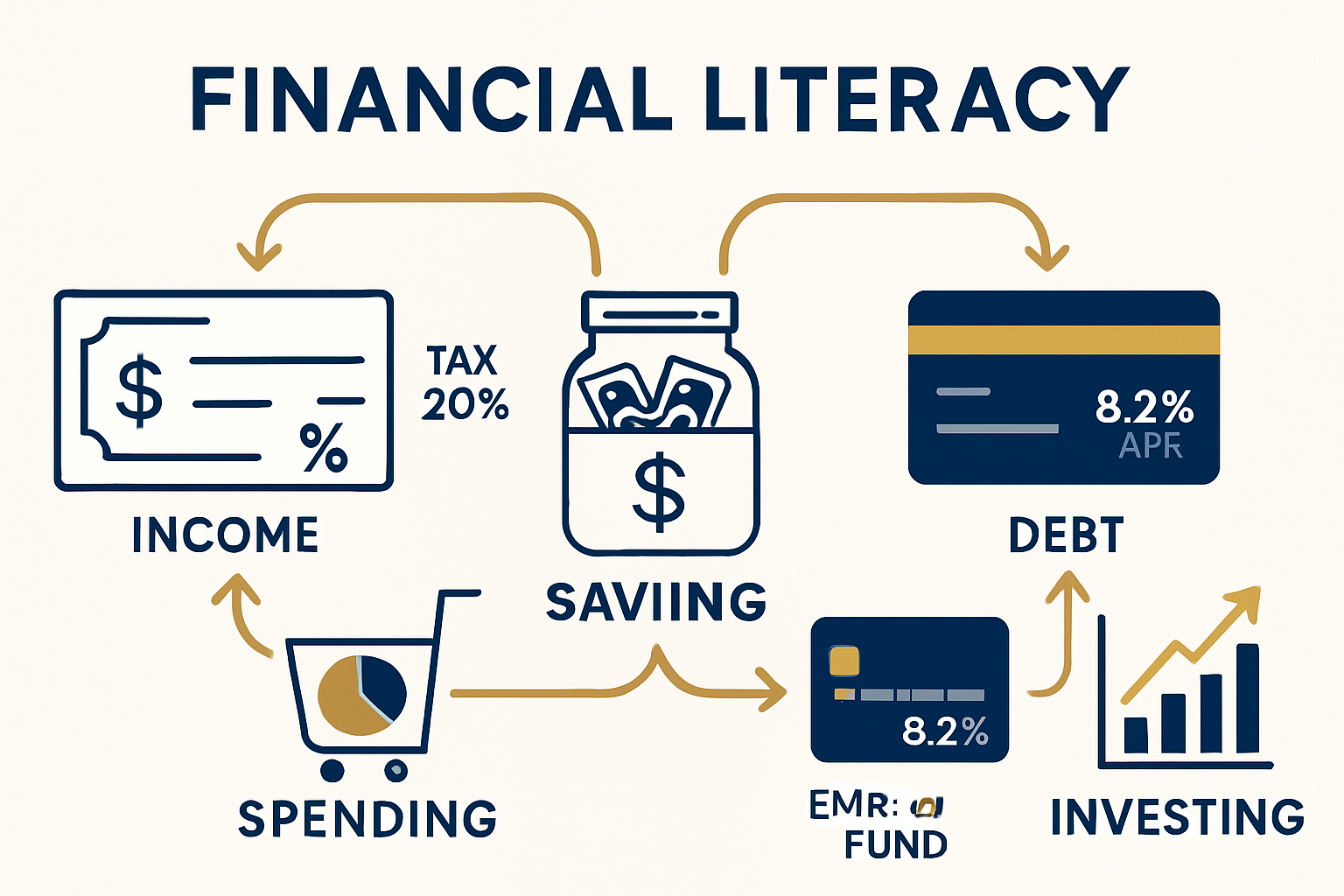

- Five core concepts form the foundation — income, spending, saving, debt, and investing work as an interconnected system.

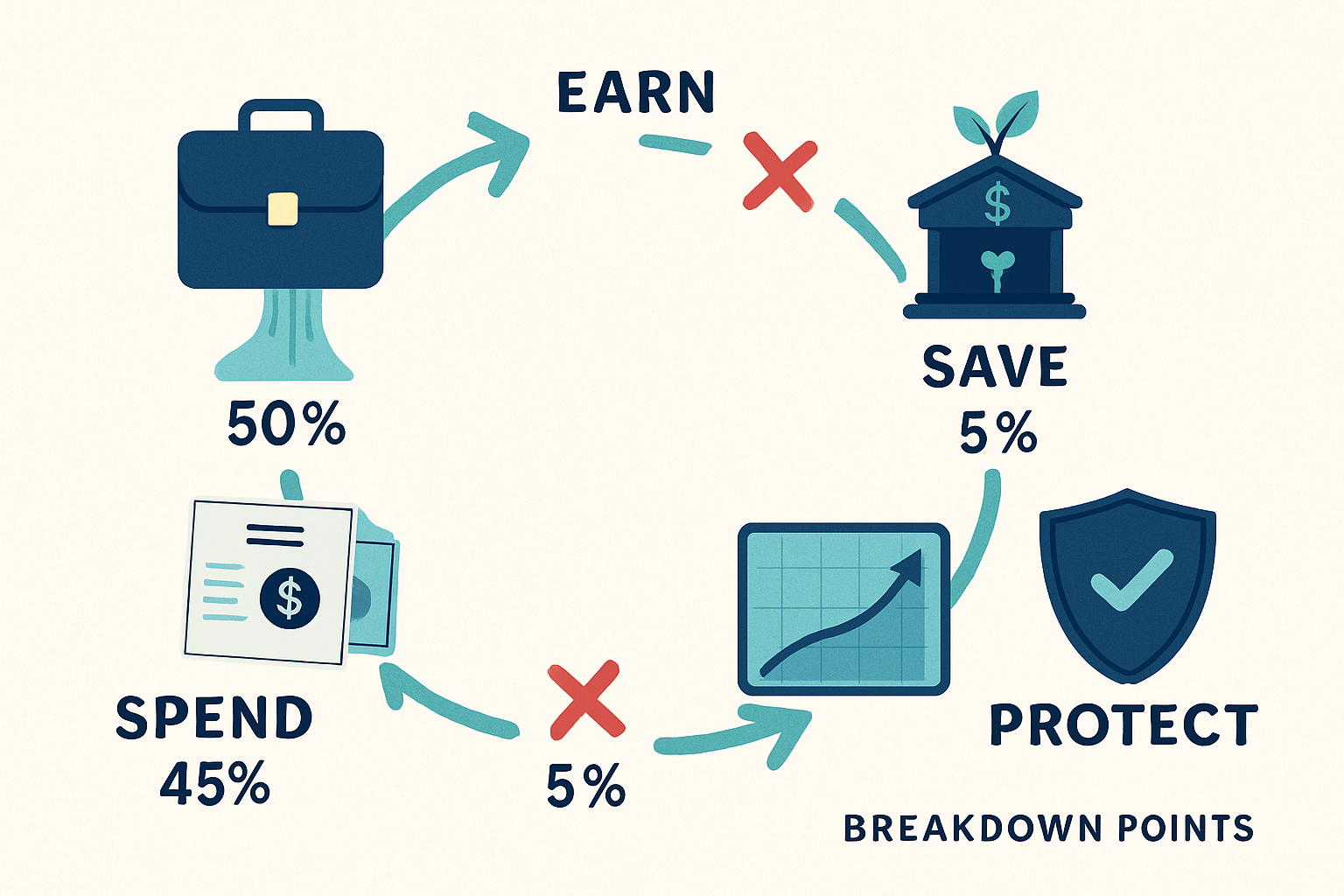

- Money flows in a specific order — earn → spend → save → invest → protect; breaking one link damages the entire chain.

- Common myths create costly mistakes — debt isn’t always bad, investing isn’t gambling, and income alone doesn’t fix poor financial habits.

- Financial literacy applies at every life stage — from building first habits to preserving retirement wealth, the principles scale with complexity.

What Is Financial Literacy?

Financial literacy means understanding how money decisions work and what consequences they create over time.

It’s not about being wealthy. It’s about making informed choices with whatever resources are available. A financially literate person earning $40,000 can build more security than someone earning $150,000 who doesn’t understand cash flow, interest, or risk.

The core skill is recognizing cause and effect: If I do X with my money, Y will happen as a result.

Why Schools Don’t Teach It

Only 25 states require high school students to take a personal finance course before graduation[1]. The education system prioritizes abstract academic subjects over practical money management. As a result, most people enter adulthood without understanding:

- How tax withholding affects paychecks

- What compound interest does to debt and investments

- How to evaluate financial trade-offs

- Why budgeting creates freedom rather than restriction

This knowledge gap has measurable consequences. According to the National Financial Educators Council, the average American lost $1,819 in 2023 due to a lack of personal finance knowledge[2].

The Real Definition

Financial literacy encompasses four key competencies:

- Understanding financial concepts — interest rates, inflation, risk, diversification

- Performing calculations — budgeting, loan comparisons, investment returns

- Making informed decisions — evaluating trade-offs between present and future value

- Taking effective action — implementing plans, adjusting behaviors, building systems

It’s both knowledge and application. Knowing what compound interest is doesn’t help unless you use that knowledge to pay down high-interest debt or start investing early.

Insight: Financial literacy isn’t a destination—it’s a continuous process of learning, applying, and refining money decisions based on evidence and outcomes.

For a broader framework on managing money effectively, see our guide on personal finance explained.

Why Financial Literacy Matters More Than Income

High income doesn’t guarantee financial security. Behavioral mistakes and knowledge gaps destroy wealth faster than low earnings.

High Income ≠ Financial Security

Professional athletes provide the clearest example. Despite earning millions, approximately 78% of NFL players face serious financial distress within two years of retirement[3]. The same pattern appears across lottery winners, entertainers, and high-income professionals.

The reason: income solves cash flow problems temporarily, but without financial literacy, the same decision-making patterns that create problems at $50,000 simply scale up at $500,000.

Common high-income financial failures:

- Lifestyle inflation — spending rises to match (or exceed) every income increase

- Debt accumulation — using credit to fund consumption beyond earnings

- Lack of emergency reserves — no buffer for job loss, medical issues, or market downturns

- Poor investment choices — chasing returns without understanding risk or fees

Behavioral Mistakes vs Math Mistakes

Two types of financial errors create problems:

Math mistakes stem from not understanding numbers:

- Not calculating the total loan cost, including interest

- Underestimating retirement savings needs

- Miscalculating take-home pay after taxes

Behavioral mistakes stem from poor decision-making despite knowing the math:

- Spending impulsively rather than according to plan

- Avoiding investment decisions due to fear or overwhelm

- Carrying credit card debt while having savings earning 0.5%

Financial literacy addresses both. It provides the mathematical framework and the decision-making clarity to recognize when emotions are overriding logic.

Compounding Bad Decisions

Small financial mistakes compound over time just like investments do—except in reverse.

Example: The $5 Daily Coffee

- Daily specialty coffee: $5

- Annual cost: $1,825

- 30-year cost at 7% investment return (opportunity cost): $173,451

This isn’t an argument against coffee. It’s a demonstration of compound effects. Every financial decision creates a cascade of future outcomes. Understanding this relationship changes how decisions get made.

The compounding effect works in both directions:

| Decision Type | Year 1 | Year 10 | Year 30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Save $200/month at 7% | $2,400 | $34,358 | $244,692 |

| Carry $5,000 credit card debt at 18% | -$900 interest | -$9,000 interest | -$27,000 interest |

| Skip employer 401(k) match (4%) on $50,000 salary | -$2,000 | -$27,633 | -$196,554 |

Each choice creates exponential consequences. Financial literacy means recognizing these patterns before they become problems.

Takeaway: Income provides raw material, but financial literacy determines what gets built with it. Decision quality beats earning power over time.

Core Financial Concepts Everyone Should Understand

Five fundamental concepts form the foundation of all money decisions. Mastering these creates the framework for every financial choice that follows.

Income

Income is money earned from labor, investments, or business activities, and what remains after taxes determines actual spending power.

Most people focus on gross income (the number on a job offer) rather than net income (what actually hits the bank account). This creates budgeting failures from day one.

Key income concepts:

- Gross income — total earnings before deductions

- Net income — take-home pay after taxes, insurance, retirement contributions

- Marginal tax rate — the percentage paid on the last dollar earned

- Effective tax rate — total taxes divided by total income

Example calculation:

Gross salary: $60,000

Federal tax (12% bracket): -$6,900

State tax (5%): -$3,000

FICA (7.65%): -$4,590

Health insurance: -$2,400

401(k) contribution (6%): -$3,600

─────────────────────────

Net income: $39,510

Monthly take-home: $3,293Understanding this breakdown prevents the common mistake of budgeting based on gross income and wondering why money runs out.

Spending

Spending is the exchange of money for goods, services, or experiences—and the distinction between needs and wants determines financial stability.

Cash flow (income minus spending) is the single most important number in personal finance. Positive cash flow creates options. Negative cash flow creates debt.

Spending categories:

- Fixed expenses — rent/mortgage, insurance, loan payments (consistent monthly amounts)

- Variable needs — groceries, utilities, transportation (necessary but fluctuating)

- Discretionary wants — entertainment, dining out, hobbies (optional spending)

The 50/30/20 budgeting framework provides a starting point:

- 50% needs

- 30% wants

- 20% savings/debt repayment

But these percentages should adjust based on goals, income level, and life circumstances. Someone earning $35,000 may need 70% for needs. Someone earning $200,000 might allocate 40% to savings.

The real principle: Spend intentionally based on values and goals, not impulsively based on availability.

Saving

Saving means setting aside money for future use—creating a buffer between current stability and unexpected events.

Savings serve three distinct purposes:

- Emergency fund — 3-6 months of expenses in liquid accounts (high-yield savings, money market)

- Short-term goals — purchases planned within 1-5 years (car, vacation, home down payment)

- Opportunity fund — capital available for time-sensitive opportunities

Emergency fund calculation:

Monthly essential expenses: $3,000

Target coverage: 6 months

Required emergency fund: $18,000This money should be:

- Accessible — withdrawable within 1-2 business days

- Stable — not subject to market volatility

- Separate — kept apart from checking accounts to prevent casual spending

As of 2025, high-yield savings accounts offer 4.0-5.0% APY, making them appropriate for emergency funds while still earning meaningful returns[4].

Insight: Savings create financial options. Without reserves, every unexpected expense becomes a crisis requiring debt.

Debt

Debt is borrowed money that must be repaid with interest, and the cost of that interest determines whether debt builds or destroys wealth.

Not all debt is equal. The distinction between productive and destructive debt matters:

Productive debt:

- Mortgages at 6-7% on appreciating assets

- Student loans for high-ROI education

- Business loans generating returns above interest cost

Destructive debt:

- Credit cards at 18-29% on consumed goods

- Auto loans on depreciating assets

- Payday loans at 400%+ APR

The math of debt:

A $5,000 credit card balance at 20% APR with minimum payments ($150/month):

- Time to payoff: 4.5 years

- Total interest paid: $3,064

- Total cost: $8,064

The same $5,000 paid off in 12 months:

- Monthly payment: $462

- Total interest paid: $555

- Total cost: $5,555

- Savings: $2,509

Debt decision framework:

- What is the interest rate?

- What is the loan used to purchase?

- Does the asset appreciate or depreciate?

- What is the opportunity cost of the payment?

These four questions reveal whether debt makes mathematical sense.

Investing

Investing means allocating money to assets expected to generate returns—and understanding the difference between growth and speculation prevents costly mistakes.

Investment vs speculation:

- Investment — buying assets based on fundamental value, cash flow, or productive capacity (stocks, bonds, real estate)

- Speculation — buying assets hoping someone will pay more later, regardless of intrinsic value (meme stocks, NFTs, lottery tickets)

Core investment principles:

- Compound growth — returns generate returns, creating exponential growth over time

- Diversification — spreading risk across multiple assets reduces portfolio volatility

- Time horizon — longer periods smooth out market volatility and increase expected returns

- Cost management — fees and taxes reduce returns; minimizing both increases wealth

Example: The power of early investing

| Scenario | Monthly Investment | Start Age | End Age | Total Invested | Final Value (7% return) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Start | $300 | 25 | 65 | $144,000 | $719,614 |

| Late Start | $600 | 40 | 65 | $180,000 | $454,513 |

The early starter invests $36,000 less but ends with $265,101 more due to compound growth over time.

This isn’t about picking stocks. It’s about understanding how time, consistency, and returns interact mathematically.

How Money Flows Through Your Life

Financial decisions don’t exist in isolation. They form a connected system where each component affects the others.

The Financial Flow Sequence

Money moves through five stages in a specific order:

1. Earn → 2. Spend → 3. Save → 4. Invest → 5. Protect

Each stage builds on the previous one. Skipping steps or reversing the order creates problems.

Stage 1: Earn

- Generate income through labor, business, or investments

- Maximize earning potential through skills, education, and negotiation

- Understand the tax implications of different income sources

Stage 2: Spend

- Cover essential needs first (housing, food, healthcare)

- Allocate discretionary spending based on values

- Track expenses to ensure alignment with goals

Stage 3: Save

- Build emergency reserves (3-6 months’ expenses)

- Fund short-term goals (1-5 year timeline)

- Create a buffer between income and expenses

Stage 4: Invest

- Allocate excess capital to growth assets

- Diversify across stocks, bonds, and real estate

- Optimize for tax efficiency and low costs

Stage 5: Protect

- Insure against catastrophic risks (health, disability, life, property)

- Create estate plans and legal protections

- Preserve wealth from lawsuits, taxes, inflation

What Happens When One Link Breaks

The sequence is interdependent. Breaking one link damages the entire chain.

Broken link: Spending exceeds earning

- Result: Debt accumulation, no savings, no investing, no protection

- Fix: Reduce spending or increase income until cash flow is positive

Broken link: No emergency savings

- Result: Unexpected expenses force debt, investment liquidation at bad times

- Fix: Pause investing temporarily to build 3-month reserve, then resume

Broken link: Investing before saving

- Result: Emergency forces selling investments at a loss to cover expenses

- Fix: Build liquid reserves first, then invest surplus

Broken link: No protection

- Result: Single catastrophic event (illness, lawsuit, death) destroys accumulated wealth

- Fix: Appropriate insurance coverage based on dependents and assets

Order of Operations

Just like mathematics has PEMDAS, personal finance has a priority sequence:

Priority 1: Earn enough to cover basic needs

Priority 2: Spend less than earnings

Priority 3: Build $1,000 emergency fund

Priority 4: Capture employer 401(k) match (free money)

Priority 5: Pay off high-interest debt (>7%)

Priority 6: Build 3-6 month emergency fund

Priority 7: Maximize tax-advantaged retirement accounts

Priority 8: Invest in taxable accounts

Priority 9: Pay off low-interest debt

Priority 10: Optimize estate planning and asset protection

This sequence maximizes mathematical efficiency. Each step provides the foundation for the next.

Takeaway: Financial success isn’t about doing everything at once—it’s about doing the right things in the right order.

For detailed strategies on managing the spend-save relationship, explore our budgeting and saving hub.

Common Financial Myths That Hurt People

Widespread misconceptions about money create expensive mistakes. Correcting these myths changes outcomes.

Myth 1: “Debt Is Always Bad”

Reality: Debt is a tool. The interest rate and purpose determine whether it’s beneficial or harmful.

A mortgage at 6.5% on a home that appreciates 4% annually while providing housing (saving rent) makes mathematical sense. A credit card at 22% used to buy depreciating consumer goods destroys wealth.

The debt evaluation framework:

- Interest rate — below 5% often acceptable, above 10% problematic

- Purpose — appreciating asset or income-generating use vs. consumption

- Payment burden — total debt payments should stay below 36% of gross income

- Opportunity cost — could the money create better returns elsewhere?

Wealthy individuals and corporations use debt strategically. The key is understanding when leverage amplifies returns versus when it amplifies risk.

Myth 2: “Investing Is Gambling”

Reality: Gambling is zero-sum with negative expected value. Investing is positive-sum with positive expected value over time.

Gambling characteristics:

- House edge ensures long-term losses

- Outcomes based purely on chance

- No underlying value creation

Investing characteristics:

- Businesses create value through products and services

- Stock market returns average 10% annually over long periods[5]

- Diversification reduces individual company risk

The S&P 500 has never produced a negative return over any 20-year period in history[6]. That’s not luck—it’s the mathematical result of productive capital compounding over time.

The confusion arises from:

- Short-term volatility (which feels like gambling)

- Speculation in individual stocks (which is closer to gambling)

- Lack of understanding about what stocks represent (ownership in businesses)

Financial literacy means recognizing the difference between buying a diversified portfolio of productive businesses and betting on short-term price movements.

Myth 3: “You Need a Lot of Money to Start”

Reality: Starting small and being consistent beats waiting for large sums.

Many brokerages now offer:

- Zero-commission trades

- Fractional shares (buy $10 of any stock)

- No account minimums

- Automatic investment plans

Example: Starting with $50/month

Monthly investment: $50

Annual return: 8%

Time period: 30 years

Final value: $67,816

Waiting 10 years to start with $150/month instead:

Monthly investment: $150

Annual return: 8%

Time period: 20 years

Final value: $82,486

The person who started earlier with less money ends with nearly as much—and invested $30,000 less total ($18,000 vs $36,000). Starting matters more than amount.

Myth 4: “More Income Fixes Everything”

Reality: Income increases without behavior changes simply scale up existing problems.

Lifestyle inflation is the tendency for spending to rise proportionally with income. A person spending 105% of $50,000 will spend 105% of $100,000 without intentional intervention.

The pattern:

| Income | Spending | Savings | Debt |

|---|---|---|---|

| $50,000 | $52,500 | $0 | +$2,500/year |

| $75,000 | $78,750 | $0 | +$3,750/year |

| $100,000 | $105,000 | $0 | +$5,000/year |

Higher income accelerates the problem rather than solving it.

The solution: Intentional allocation of raises and bonuses:

- 50% to savings/investing

- 25% to debt reduction

- 25% to lifestyle improvement

This formula allows quality of life to improve while simultaneously building wealth.

Insight: Financial problems are rarely income problems—they’re behavior and knowledge problems. Financial literacy addresses root causes rather than symptoms.

Financial Literacy by Life Stage

Money principles remain constant, but their application changes as life circumstances evolve.

Beginners (Ages 18-25)

Primary focus: Build foundational habits and avoid early mistakes.

Key priorities:

- Establish positive cash flow — spend less than earned, even if margins are small

- Start emergency fund — target $1,000, then build to 3 months expenses

- Avoid consumer debt — no credit card balances, minimize student loans

- Begin investing early — even $25/month in a Roth IRA creates massive long-term value

- Build credit responsibly — one credit card paid in full monthly

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Lifestyle inflation with first real paycheck

- Financing depreciating assets (cars, electronics)

- Skipping employer retirement match

- Ignoring student loan interest accumulation

Math that matters at this stage:

Starting retirement investing at 22 vs 32:

- $200/month from age 22-65 at 8% = $816,765

- $200/month from age 32-65 at 8% = $351,428

- Cost of waiting 10 years: $465,337

The beginner stage offers the most valuable asset: time. Using it creates exponential advantages.

Working Professionals (Ages 26-45)

Primary focus: Optimize earnings, accelerate wealth building, and add protection layers.

Key priorities:

- Maximize income growth — skills development, career advancement, negotiation

- Increase savings rate — target 15-20% of gross income minimum

- Tax optimization — max out 401(k), HSA, IRA contributions ($23,000 + $4,150 + $7,000 = $34,150 in 2025[7])

- Diversified investing — stocks, bonds, real estate based on risk tolerance

- Adequate insurance — term life insurance (10-12x income if dependents), disability insurance

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Lifestyle inflation consuming all raises

- Chasing investment fads without understanding fundamentals

- Underinsuring catastrophic risks

- Neglecting estate planning documents

Optimization opportunities:

| Strategy | Annual Tax Savings (24% bracket) |

|---|---|

| Max 401(k) contribution | $5,520 |

| Max HSA contribution | $996 |

| Max IRA contribution | $1,680 |

| Total tax reduction | $8,196 |

These aren’t just savings—they’re investments growing tax-deferred or tax-free.

Families (Ages 30-55)

Primary focus: Balance current needs with future security while managing increased complexity.

Key priorities:

- Increased emergency reserves — 6-12 months expenses (higher due to dependents)

- Education funding — 529 plans, understanding financial aid implications

- Comprehensive insurance — life insurance covering income replacement, umbrella liability ($1-5M coverage)

- Estate planning — wills, trusts, guardianship designations, powers of attorney

- Teaching children — financial literacy education, modeling healthy money behaviors

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Overfunding college at expense of retirement

- Inadequate life insurance coverage

- No estate plan or outdated documents

- Sacrificing parents’ financial security for children’s wants

The retirement vs college funding priority:

Retirement: No loans available, must be self-funded

College: Loans, scholarships, work-study available

The mathematically correct priority is retirement first, college second. A parent can’t borrow for retirement, but students can borrow for education.

Recommended allocation of surplus income:

- 60% retirement savings

- 20% college savings

- 20% other goals (home, experiences, giving)

Pre-Retirement (Ages 50-65)

Primary focus: Preserve accumulated wealth and optimize transition to distribution phase.

Key priorities:

- Catch-up contributions — additional $7,500 to 401(k), $1,000 to IRA for age 50+[8]

- Debt elimination — pay off mortgage and all consumer debt before retirement

- Healthcare planning — bridge coverage until Medicare at 65, long-term care insurance evaluation

- Social Security optimization — understand claiming strategies (delay to 70 increases benefit 24%)

- Withdrawal strategy — tax-efficient distribution planning from multiple account types

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Taking Social Security too early (age 62 vs 70 = 76% benefit difference)

- Aggressive investing too close to retirement

- Underestimating healthcare costs ($315,000 average for couple in retirement[9])

- No plan for required minimum distributions (RMDs) starting at age 73

Preservation vs growth allocation:

| Age | Stock % | Bond % | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 70% | 30% | Still growth-focused |

| 60 | 60% | 40% | Balanced approach |

| 65 | 50% | 50% | Preservation emphasis |

The “100 minus age” rule provides a starting point for stock allocation, but individual circumstances (pension, risk tolerance, health) should adjust this.

Takeaway: Financial literacy isn’t one-size-fits-all—it’s the ability to apply core principles appropriately as circumstances change.

How Financial Literacy Connects Every Money Decision

Understanding how money works creates a framework that improves every financial choice.

The Integration of Financial Concepts

Each financial domain connects to the others. Decisions in one area create ripple effects throughout the system.

Example: Buying a car

A simple car purchase involves:

- Credit — loan terms, interest rate, credit score impact

- Budgeting — monthly payment, insurance, maintenance, fuel costs

- Opportunity cost — what else could the money accomplish?

- Depreciation — asset value decline (new cars lose 20% in year one[10])

- Insurance — comprehensive, collision, liability coverage needs

- Tax implications — sales tax, registration fees, potential deductions if business use

Financially literate approach:

- Determine actual transportation need (not want)

- Calculate total cost of ownership (purchase + insurance + maintenance + fuel)

- Compare to alternatives (used car, public transit, car-sharing)

- Evaluate financing options (cash, low-rate loan, lease)

- Consider opportunity cost (what investment returns could the cash generate?)

- Make decision based on total financial impact, not monthly payment

Financially illiterate approach:

- See car, want car

- Ask “what’s the monthly payment?”

- Sign whatever paperwork makes that payment happen

- Ignore total cost, interest, insurance increases, depreciation

The difference isn’t intelligence—it’s framework. Financial literacy provides the framework.

Connected Financial Domains

Understanding how these areas interact improves decision-making across all of them:

Credit and Debt Management

How borrowing decisions affect long-term wealth and what strategies minimize interest costs. For comprehensive coverage, see our guide on credit and debt explained.

Investment Strategy

How to allocate capital across asset classes to balance growth and risk. Learn the fundamentals in our investing explained resource.

Risk Protection

How insurance transfers catastrophic financial risk and when coverage makes mathematical sense. Explore options in our insurance explained guide.

Retirement Planning

How to accumulate and preserve wealth for financial independence. Understand the complete picture in our retirement explained framework.

The Compound Effect of Small Improvements

Financial literacy doesn’t require perfection—it requires consistent improvement.

Example: 1% optimization across five areas

| Area | Annual Impact |

|---|---|

| Reduce expenses 1% on $50,000 spending | +$500 |

| Negotiate 1% salary increase on $60,000 | +$600 |

| Reduce investment fees from 1% to 0.5% on $100,000 | +$500 |

| Refinance debt saving 1% on $20,000 | +$200 |

| Tax optimization reducing effective rate 1% | +$600 |

| Total annual improvement | +$2,400 |

Invested at 8% for 30 years: $272,869

Small improvements compound just like investments do. Financial literacy is the skill of identifying and implementing these optimizations systematically.

Tools That Improve Financial Literacy

Practical tools transform abstract concepts into actionable insights.

Budget Calculators

Purpose: Track income and expenses to ensure spending aligns with goals.

Key features to look for:

- Income and expense categorization

- Visual spending breakdowns (pie charts, trend graphs)

- Budget vs actual comparisons

- Mobile accessibility for real-time tracking

Popular options:

- Mint (free, automated transaction categorization)

- YNAB – You Need A Budget (paid, zero-based budgeting methodology)

- Personal Capital (free, investment tracking integrated)

- Spreadsheet templates (Google Sheets, Excel)

What to track:

- Fixed expenses (rent, insurance, loan payments)

- Variable needs (groceries, utilities, gas)

- Discretionary spending (dining, entertainment, subscriptions)

- Savings and investments

- Debt payments

The act of tracking creates awareness. Awareness changes behavior.

Retirement Estimators

Purpose: Calculate required savings to maintain desired lifestyle in retirement.

Key inputs:

- Current age and retirement age

- Current savings and contribution rate

- Expected investment return

- Desired retirement income

- Social Security estimates

- Life expectancy

Useful calculators:

- Social Security Administration calculator (ssa.gov/benefits/retirement/estimator.html)

- Vanguard Retirement Income Calculator

- Fidelity Retirement Score

- Personal Capital Retirement Planner

Example calculation:

Desired retirement income: $60,000/year

Social Security: $24,000/year

Gap to fund: $36,000/year

Using 4% withdrawal rule: $900,000 needed

Current age: 35

Retirement age: 65

Years to save: 30

Required monthly investment at 7%: $751These tools convert abstract future needs into concrete present actions.

Net Worth Trackers

Purpose: Measure total financial position by tracking assets minus liabilities over time.

Net worth formula:

Assets (what you own):

+ Cash and savings

+ Investment accounts

+ Retirement accounts

+ Real estate equity

+ Business value

+ Personal property

Liabilities (what you owe):

- Mortgage balance

- Student loans

- Auto loans

- Credit card debt

- Other debts

─────────────────

= Net WorthWhy it matters:

Net worth is the single best measure of financial progress. Income and expenses fluctuate, but net worth shows the cumulative result of all financial decisions.

Tracking frequency: Monthly or quarterly

What to look for: Consistent upward trend, even if growth is small initially

Example progression:

| Age | Assets | Liabilities | Net Worth | Annual Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | $15,000 | $35,000 | -$20,000 | – |

| 30 | $75,000 | $28,000 | $47,000 | +$13,400/year |

| 35 | $185,000 | $15,000 | $170,000 | +$24,600/year |

| 40 | $380,000 | $5,000 | $375,000 | +$41,000/year |

The acceleration happens because:

- Debt decreases (interest stops compounding against you)

- Investments increase (returns start compounding for you)

- Income typically grows with career progression

- Financial literacy improves decision quality

Insight: Tools don’t create financial literacy—they make it actionable. The knowledge guides what to track; the tracking reveals what to improve.

📊 Financial Literacy Self-Assessment

Test your knowledge and discover your current financial literacy level

Conclusion

Financial literacy is the skill of understanding how money decisions create future outcomes—and applying that understanding to build security, opportunity, and freedom.

It’s not about complex formulas or advanced investing strategies. It’s about mastering fundamentals:

Spend less than you earn — positive cash flow creates all other possibilities

Build emergency reserves — liquidity prevents forced bad decisions

Avoid high-interest debt — interest compounds against you exponentially

Invest consistently — time and compound growth do the heavy lifting

Protect what you build — insurance transfers catastrophic risk

These principles work regardless of income level, market conditions, or economic environment. They’re mathematical truths, not opinions.

Actionable Next Steps

If you’re just starting:

- Track spending for 30 days to understand current patterns

- Build a $1,000 emergency fund

- Capture any employer retirement match

- Set up automatic savings (even $25/month creates the habit)

If you’re optimizing:

- Calculate your actual savings rate (savings ÷ gross income)

- Identify the highest-interest debt and create an elimination plan

- Review investment fees (target under 0.20% for index funds)

- Increase retirement contributions by 1% every 6 months

If you’re preserving:

- Project retirement income from all sources

- Develop tax-efficient withdrawal strategy

- Review estate planning documents

- Optimize Social Security claiming strategy

The Compound Effect of Knowledge

Financial literacy compounds just like investments. Each concept learned improves future decisions. Each improved decision creates better outcomes. Better outcomes create more resources. More resources create more opportunities.

The difference between financial stress and financial confidence isn’t luck, inheritance, or income level. It’s understanding cause and effect—and making decisions accordingly.

Start with one concept. Master it. Apply it. Move to the next.

The math behind money isn’t complicated. It’s just rarely taught. Now you know how it works.

Related Guides

Expand your financial knowledge with these comprehensive resources:

- Learning Personal Finance — Complete framework for managing money effectively

- Understanding Money Basics — Foundational concepts every adult should know

- Making Better Financial Decisions — Decision-making frameworks that improve outcomes

- Improving Financial Confidence — Building competence through knowledge and action

References

[1] Council for Economic Education. (2024). “Survey of the States: Economic and Personal Finance Education in Our Nation’s Schools.” Retrieved from https://www.councilforeconed.org/

[2] National Financial Educators Council. (2023). “National Financial Literacy Test Results.” Retrieved from https://www.financialeducatorscouncil.org/

[3] National Bureau of Economic Research. (2015). “The Lifecycle of Professional Football Players: Earnings and Post-Career Outcomes.” Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/

[4] Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2025). “National Rates and Rate Caps.” Retrieved from https://www.fdic.gov/

[5] NYU Stern School of Business. (2024). “Historical Returns on Stocks, Bonds and Bills: 1928-2024.” Retrieved from https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/

[6] Morningstar. (2024). “Long-Term Returns of the S&P 500.” Retrieved from https://www.morningstar.com/

[7] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “401(k) Contribution Limits and IRA Contribution Limits.” Retrieved from https://www.irs.gov/

[8] Internal Revenue Service. (2025). “Retirement Topics – Catch-Up Contributions.” Retrieved from https://www.irs.gov/

[9] Fidelity Investments. (2024). “How to Plan for Rising Health Care Costs in Retirement.” Retrieved from https://www.fidelity.com/

[10] Kelley Blue Book. (2024). “New Car Depreciation Rates.” Retrieved from https://www.kbb.com/

Educational Disclaimer

This content is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. The information presented represents general principles and concepts related to financial literacy and should not be considered personalized recommendations for your specific situation.

Financial decisions involve risk and should be made based on individual circumstances, goals, risk tolerance, and after consultation with qualified financial, tax, and legal professionals. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Investment returns and principal value will fluctuate.

The Rich Guy Math and its authors make no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information provided. Market conditions, tax laws, and financial regulations change frequently and may affect the applicability of the concepts discussed.

Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and due diligence before making any financial decisions. No content on this site should be interpreted as a guarantee of specific outcomes or results.

About the Author

Max Fonji is the founder of TheRichGuyMath.com and a dedicated financial educator focused on making complex money concepts accessible through clear explanations and data-driven analysis.

With a background in financial analysis and a passion for teaching, Max specializes in breaking down the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investment strategy, and financial decision-making. His approach combines rigorous analytical frameworks with plain-English explanations to help readers understand not just what to do with money, but why certain strategies work.

Max’s educational philosophy centers on evidence-based learning: every financial concept should be supported by data, every recommendation should show its mathematical logic, and every reader should finish with actionable knowledge they can immediately apply.

Through The Rich Guy Math, Max provides comprehensive guides on personal finance, investing fundamentals, risk management, and the quantitative principles that govern long-term wealth creation—all designed to build genuine financial literacy rather than promote specific products or services.

Connect: TheRichGuyMath.com | Focus: Financial literacy, investment mathematics, data-driven money education.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does it mean to be financially literate?

Being financially literate means understanding how money decisions work and what consequences they create over time. It includes knowing how to budget, save, invest, manage debt, and protect wealth—and, more importantly, applying that knowledge to make informed choices that improve long-term outcomes.

Financial literacy isn’t about being wealthy; it’s about making effective decisions with whatever resources are available.

Can financial literacy really change outcomes?

Yes—measurably. Research shows financially literate individuals are more likely to plan for retirement, diversify investments, and avoid high-cost debt.

The National Financial Educators Council estimates that lack of personal finance knowledge cost Americans an average of $1,819 per person in 2023. Understanding concepts like compound interest, tax efficiency, and risk management can add hundreds of thousands of dollars to lifetime wealth without increasing income.

Is financial literacy more important than investing?

Financial literacy includes investing knowledge, but it’s much broader. Someone can invest aggressively and still struggle financially if they carry high-interest debt, lack emergency savings, or have no insurance.

Financial literacy provides the framework that determines whether to invest, how much to invest, what to invest in, and when to adjust strategy. Investing is one tool—financial literacy is the full toolkit.

Where should beginners start?

Beginners should start with cash flow awareness. Track every dollar earned and spent for 30 days to understand current habits.

Next, build a $1,000 emergency fund to prevent small emergencies from becoming debt. Then capture any employer retirement match—it’s guaranteed return. Finally, learn one concept at a time, such as how interest works, what compound growth means, and why diversification matters, applying each concept before moving on.

How long does it take to become financially literate?

Basic financial literacy—covering budgeting, saving, debt management, and simple investing—can be achieved in 3 to 6 months with consistent learning and application.

Advanced topics like tax optimization, estate planning, and alternative investments take years to master. The goal isn’t perfection—it’s continuous improvement. Every concept learned and applied improves outcomes immediately.