Understanding your credit card or bank account balances is more than just checking numbers; it’s about managing your money wisely and avoiding unnecessary fees or interest. Two terms are often confused: statement balance and current balance. While they might seem similar, they serve different purposes and can impact your payments, credit utilization, and overall financial health.

This article is part of our complete Credit Cards Guide, where we break down APRs, interest, rewards, fees, and how to use credit cards the smart way.

In this guide, we’ll break down the key differences between statement balance and current balance, explain when to pay each, and provide practical examples so you can avoid mistakes and make informed financial decisions. By the end, you’ll confidently know which balance to track and how it affects your credit score and interest charges.

Key Takeaways

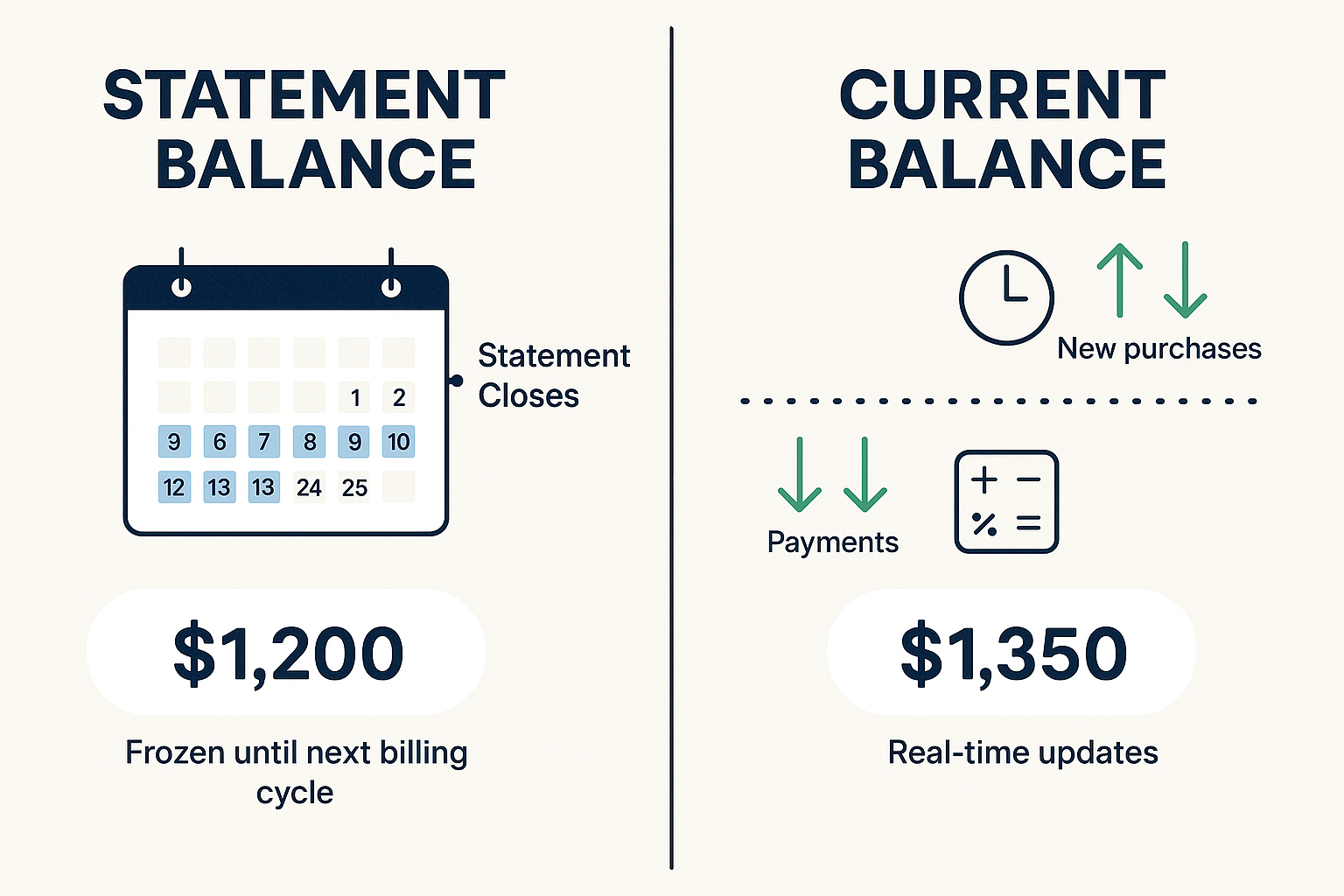

- Statement balance is a fixed snapshot of what you owed at the end of your billing cycle; current balance updates in real-time with every transaction

- Pay your statement balance in full by the due date to avoid interest charges and maintain your grace period protection

- Paying your current balance brings your account to $0, but it isn’t required to avoid interest; it primarily benefits your credit utilization ratio

- The difference between these balances equals transactions posted after your statement closing date (new purchases, payments, credits, or refunds)

- Missing the statement balance payment triggers interest on your entire balance, not just the unpaid portion, a costly mathematical reality most cardholders don’t understand

What Is Statement Balance?

Statement balance is the total amount you owed on your credit card at the exact moment your billing cycle ended.

Think of it as a financial snapshot. Your credit card issuer closes the books on a specific date, typically every 28 to 31 days, and calculates everything you charged, paid, and any fees or interest that were posted during that period.

This number freezes in time. It doesn’t change, even if you make new purchases or payments the next day.

The Math Behind Statement Balance

Your statement balance follows this formula:

Statement Balance = Previous Balance + New Purchases + Fees + Interest – Payments – Credits

All variables in this equation reflect only transactions that were posted during the billing cycle.

Example:

- Previous balance: $500

- New purchases during cycle: $750

- Annual fee posted: $95

- Payment made during cycle: -$500

- Refund credited: -$45

Statement Balance = $500 + $750 + $95 + $0 – $500 – $45 = $800

This $800 becomes your official statement balance. It appears on your monthly statement and remains constant until the next billing cycle closes.

Why Statement Balance Matters

Your statement balance determines your minimum payment and your interest-free grace period.

The Credit CARD Act of 2009 requires issuers to give you at least 21 days from statement issuance to the payment due date. During this window, if you pay the full statement balance, you owe zero interest on those purchases.

This is the cornerstone of using credit cards as a financial tool rather than a debt trap.

Insight: Your statement balance is the only number that matters for avoiding interest charges. Everything else is secondary.

What Is Current Balance?

Current balance is the total amount you owe on your credit card right now; this very moment.

Unlike statement balance, current balance is dynamic. It updates continuously (or within 1-2 business days, depending on transaction processing) as new charges post, payments clear, and interest accrues.

Your current balance includes:

- All transactions from your last statement

- New purchases made after the statement closed

- Pending or recently posted payments

- Credits, refunds, or adjustments

- Any new interest or fees

The Real-Time Nature of Current Balance

Current balance operates on a rolling basis. Check your account Monday morning, and you might see $1,350. Make a $50 payment Monday afternoon, and your current balance drops to $1,300 within hours or by Tuesday.

This real-time updating makes the current balance useful for tracking your spending and available credit, but it’s not the number that determines your interest charges.

Current Balance Formula

Current Balance = Statement Balance + New Transactions – New Payments + New Fees/Interest

The “new” variables represent everything that happened after your statement closing date.

Example:

- Statement balance (closed March 15): $1,200

- New purchase on March 17: $100

- Payment posted March 18: -$200

- New purchase on March 20: $50

Current Balance (as of March 20) = $1,200 + $100 + $50 – $200 = $1,150

Your current balance dropped below your statement balance because you made a payment larger than your new purchases.

Insight: Current balance tells you what you owe today. Statement balance tells you what you must pay to avoid interest.

Statement Balance vs Current Balance: Key Differences

The distinction between these two balances creates confusion, but the math is straightforward.

| Feature | Statement Balance | Current Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Amount owed at billing cycle end | Amount owed right now |

| Updates | Once per billing cycle | Continuously (real-time) |

| Includes | Only transactions during closed cycle | All transactions through today |

| Purpose | Determines interest and minimum payment | Shows total current debt |

| Required Payment | Must pay to avoid interest | Optional to pay in full |

| Changes After Statement | No, remains fixed | Yes, updates with activity |

| Grace Period Protection | Not relevant to grthe ace period | Not relevant to the ace period |

Interest Implications: The Critical Difference

Here’s where the math becomes expensive if you don’t understand the mechanics.

Grace Period Rule:

Pay your statement balance in full by the due date = $0 interest on purchases from that cycle.

Pay anything less than your statement balance = interest accrues on your entire average daily balance, not just the unpaid portion.

This is a common misconception. Many cardholders believe paying most of their statement balance means they’ll only pay interest on the small remaining amount. That’s incorrect.

Example:

- Statement balance: $2,000

- You pay: $1,900 (thinking you’ll only pay interest on $100)

- APR: 24.99%

- Average daily balance: $2,000

Reality: You lose your grace period. Interest accrues on the full $2,000 average daily balance for the entire billing cycle, not just the $100 you didn’t pay.

Daily interest rate = 24.99% ÷ 365 = 0.0685% per day

Interest for 30-day cycle ≈ $2,000 × 0.0685% × 30 = $41.10

You paid 95% of your statement balance but still incurred $41 in interest charges.

This mathematical reality is why paying the full statement balance matters so much. It’s binary: full payment = no interest; partial payment = interest on everything.

When Current Balance Exceeds Statement Balance

This happens when you make new purchases after your statement closes.

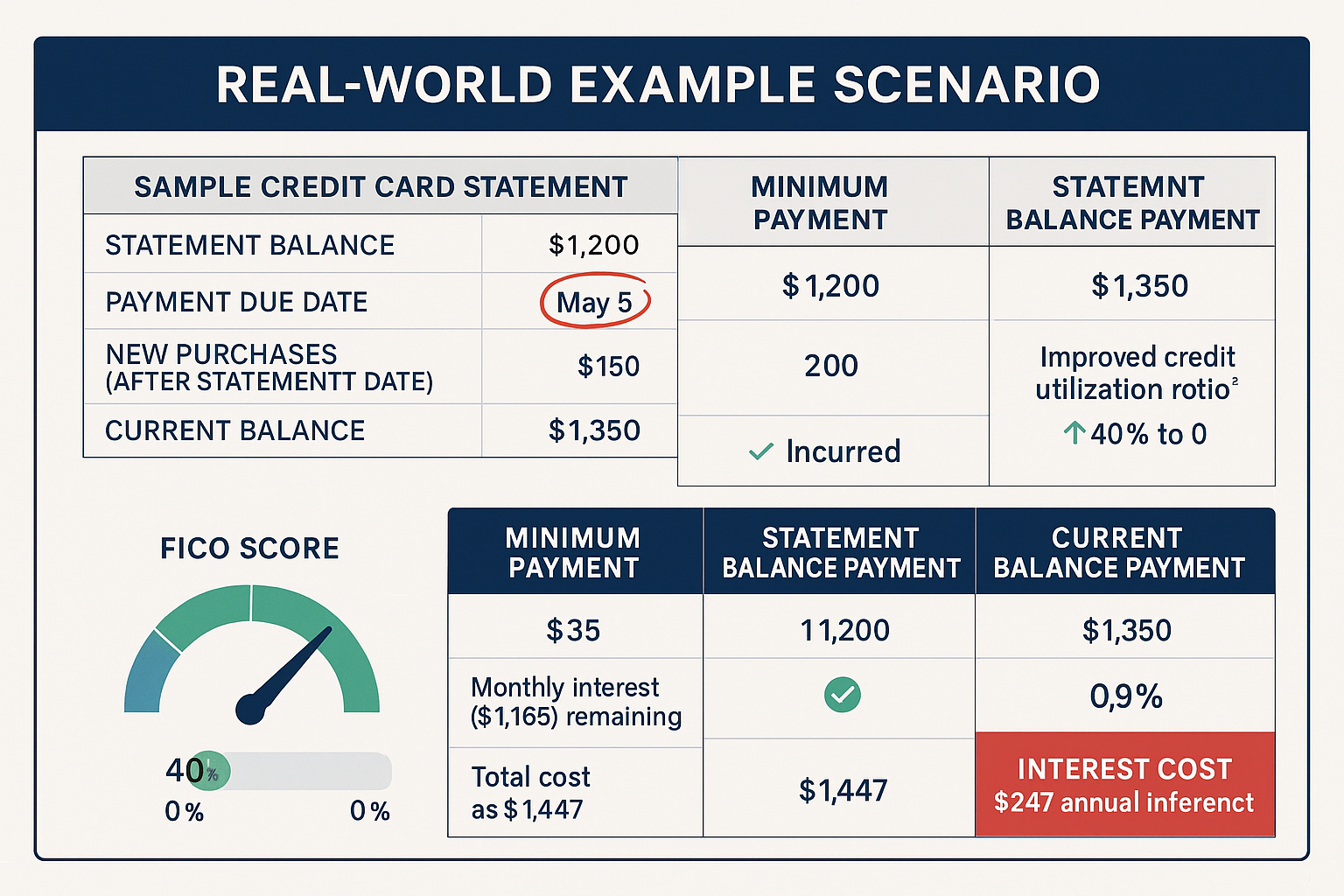

Scenario:

- Statement balance (closed April 5): $1,200

- New purchase April 7: $150

- Current balance (April 7): $1,350

You only need to pay $1,200 by the due date to avoid interest on the April 5 statement cycle. The $150 new purchase rolls into the next billing cycle and won’t incur interest if you pay that statement balance in full by its due date.

When the Current Balance Is Lower Than the Statement Balance

This occurs when you make payments or receive credits after the statement closes.

Scenario:

- Statement balance (closed April 5): $1,200

- Payment posted April 8: -$300

- Current balance (April 8): $900

You still owe the full $1,200 statement balance to preserve your grace period. The $300 payment reduces your current balance but doesn’t change your statement balance requirement.

If you only pay $900 (your current balance), you’ll lose your grace period and incur interest on the original $1,200 average daily balance.

Takeaway: Statement balance is your contractual obligation for interest avoidance. Current balance is informational.

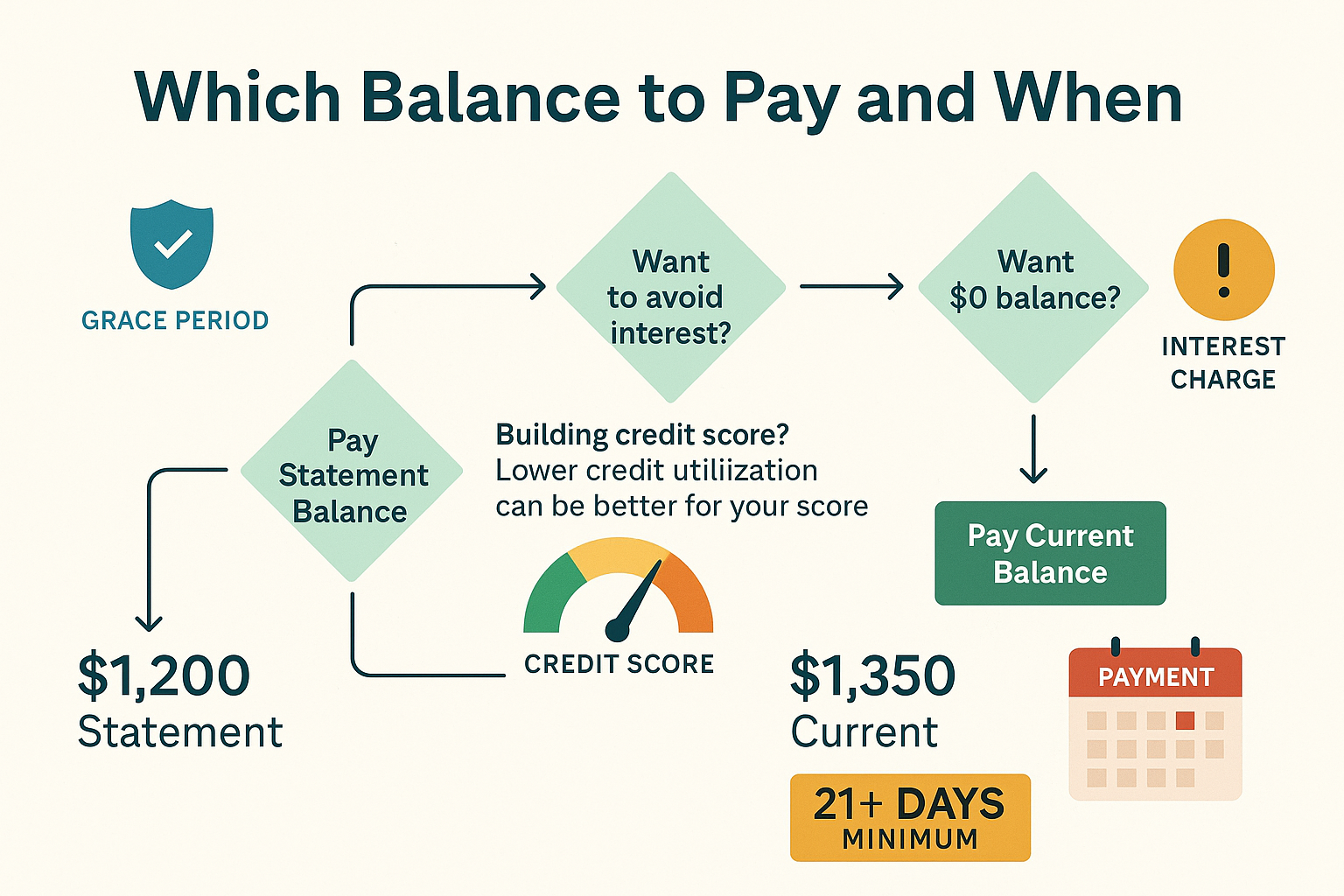

Which Balance Should You Pay?

The data-driven answer depends on your financial goals and credit strategy.

Decision Framework: Which Balance to Pay

Pay Statement Balance If:

- You want to avoid all interest charges

- You want to maintain your grace period

- You have sufficient cash flow to cover the full amount

- You’re optimizing for cost minimization

Pay Current Balance If:

- You want to bring your balance to $0

- You’re actively managing your credit utilization ratio for credit score optimization

- You want to maximize available credit immediately

- You prefer the psychological benefit of a zero balance

Pay Minimum Payment Only If:

- You’re experiencing temporary cash flow constraints

- You understand you’ll pay significant interest

- You have a plan to pay the full balance soon

The Grace Period Explained

Your grace period is the interest-free window between your statement closing date and payment due date.

Grace Period = Statement Closing Date → Payment Due Date (minimum 21 days)

During this period, your purchases don’t accrue interest—but only if you pay the full statement balance by the due date.

Once you carry a balance (pay less than the statement balance), you lose the grace period on new purchases. Every transaction starts accruing interest immediately from the purchase date until you pay the full balance for two consecutive billing cycles.

Example of Grace Period Loss:

Month 1:

- Statement balance: $1,000

- You pay: $800

- Result: Grace period lost; interest accrues on $1,000

Month 2:

- New purchases: $500

- Previous unpaid balance: $200

- Interest from Month 1: $15

- Statement balance: $715

- You pay: $715 (full statement balance)

- Result: Grace period still not restored; new $500 in purchases accrues interest immediately

Month 3:

- New purchases: $300

- Interest from Month 2: $8

- Statement balance: $308

- You pay: $308 (full statement balance)

- Result: Grace period restored for Month 4

It takes two consecutive months of paying the full statement balance to restore your grace period.

This mathematical reality makes carrying a balance extremely expensive. The compound effect of losing your grace period can cost hundreds or thousands in interest annually.

The Math: Statement Balance vs Current Balance Payment

Let’s compare three payment strategies with real numbers.

Assumptions:

- Statement balance: $2,500

- Current balance: $2,700 (includes $200 in new purchases after statement)

- APR: 21.99%

- Monthly spending: $2,500 average

Strategy 1: Pay Minimum ($75)

- Interest charged: ~$45.62 per month

- Annual interest cost: ~$547.44

- Balance after 12 months: $3,047 (assuming no new purchases)

- Grace period: Lost

Strategy 2: Pay Statement Balance ($2,500)

- Interest charged: $0

- Annual interest cost: $0

- Balance after payment: $200 (new purchases)

- Grace period: Maintained

Strategy 3: Pay Current Balance ($2,700)

- Interest charged: $0

- Annual interest cost: $0

- Balance after payment: $0

- Grace period: Maintained

- Credit utilization: Drops to 0% (optimal for credit score)

The difference between Strategy 1 and Strategy 2 is $547.44 per year, money that could compound in an investment account instead of enriching your credit card issuer.

Strategy 3 costs an extra $200 upfront compared to Strategy 2, but provides marginal credit score benefits through lower utilization.

Insight: For most cardholders, paying the statement balance in full represents the optimal balance between cash flow management and interest avoidance.

Real-World Examples: Statement Balance vs Current Balance

Let’s examine concrete scenarios with actual dollar amounts to demonstrate how these balances work in practice.

Example 1: Standard Monthly Usage

Timeline:

- March 1-31: Billing cycle

- March 31: Statement closes

- April 21: Payment due date

Activity During March:

- Starting balance: $0

- March 5: Grocery store, $150

- March 12: Gas station, $60

- March 18: Online shopping, $300

- March 25: Restaurant, $85

- March 28: Payment posted, -$200

Statement Balance (March 31): $395

($0 + $150 + $60 + $300 + $85 – $200)

Activity After Statement Closes:

- April 3: Coffee shop, $15

- April 8: Utility bill autopay, $120

- April 10: Payment posted, -$200

Current Balance (April 10): $330

($395 + $15 + $120 – $200)

What to Pay:

Pay $395 (statement balance) by April 21 to avoid interest, even though your current balance is only $330.

If you only pay $330, you’ll lose your grace period because you didn’t pay the full statement balance.

Example 2: Large Purchase After Statement Closes

Scenario:

- Statement balance (April 15): $1,200

- April 18: MacBook purchase, $1,500

- Current balance (April 18): $2,700

- Payment due: May 6

Decision:

You don’t need to pay $2,700 to avoid interest. The $1,500 MacBook purchase will appear on your next statement (closing around May 15) and won’t incur interest if you pay that statement balance in full.

Optimal Payment: $1,200 by May 6

Result:

- Zero interest on the April statement

- $1,500 rolls to May statement

- Grace period maintained

- You keep $1,500 in your checking account for an extra 30+ days

This demonstrates the cash flow advantage of understanding the difference between the statement and the current balance.

Example 3: Multiple Payments Throughout the Month

Scenario:

- Statement balance (May 10): $3,000

- May 15: Payment, -$1,000

- May 20: New purchase, $400

- May 25: Payment, -$1,500

- May 28: Refund posted, -$100

- Current balance (May 28): $800

- Payment due: May 31

Calculation:

- Statement balance: $3,000 (fixed)

- Total payments after statement: -$2,500

- New charges after statement: +$400

- Refund: -$100

- Current balance: $800

What You Owe:

You’ve already paid $2,500 toward your $3,000 statement balance. You still owe $500 by May 31 to avoid interest, not $800.

The $400 new purchase and -$100 refund are part of the next billing cycle.

Optimal Payment: $500 by May 31

This example shows why tracking your statement balance separately from your current balance prevents overpayment while maintaining your grace period.

Example 4: The Minimum Payment Trap

Scenario:

- Statement balance: $5,000

- Minimum payment: $150 (3% of balance)

- APR: 24.99%

- You pay: $150

What Happens:

Month 1:

- Interest charged: $104.13 (5,000 × 24.99% ÷ 12)

- Principal reduction: $45.87 ($150 – $104.13)

- New balance: $4,954.13

Month 2:

- Interest charged: $103.17

- Principal reduction: $46.83

- New balance: $4,907.30

Paying minimum only:

- Time to pay off: 23 years, 4 months

- Total interest paid: $13,403

- Total paid: $18,403 (for a $5,000 balance)

If you paid the statement balance in full:

- Time to pay off: 1 month

- Total interest paid: $0

- Total paid: $5,000

The minimum payment trap demonstrates why understanding your statement balance obligation is crucial for wealth building. That $13,403 in interest could have compounded in an investment account instead.

Insight: Minimum payments are mathematically designed to maximize issuer profit and minimize principal reduction. They’re a wealth-destruction mechanism disguised as affordability.

How Statement Balance vs Current Balance Affects Your Credit Score

Your credit score doesn’t directly track whether you pay your statement balance or current balance. Instead, it measures your credit utilization ratio; the percentage of available credit you’re using.

Credit Utilization Calculation

Credit Utilization = (Current Balance ÷ Credit Limit) × 100

Most credit card issuers report your balance to credit bureaus on your statement closing date. This means your statement balance typically determines your reported utilization, not your current balance.

Example:

- Credit limit: $10,000

- Statement balance (reported): $3,000

- Current balance (after paying statement): $500

Reported utilization: 30% ($3,000 ÷ $10,000)

Even though you paid your balance down to $500, the credit bureaus see 30% utilization because that’s what was reported on your statement date.

Optimal Utilization Strategy

Credit scoring models (FICO, VantageScore) favor low utilization:

- 0-9% utilization: Optimal for credit scores

- 10-29% utilization: Good, minimal score impact

- 30-49% utilization: Moderate negative impact

- 50%+ utilization: Significant negative impact

- 100% utilization: Maximum negative impact

Strategy to Optimize Utilization:

Option 1: Pay Before Statement Closes

Make a payment before your statement closing date to reduce your reported balance.

Example:

- Credit limit: $10,000

- Charges during cycle: $4,000

- Payment before statement closes: -$3,000

- Statement balance: $1,000

- Reported utilization: 10% (instead of 40%)

Option 2: Pay Current Balance in Full

Pay your current balance to bring utilization to 0%, then let new charges post.

Example:

- Statement balance: $2,000

- Current balance: $2,200

- Pay: $2,200

- New charges before next statement: $500

- Next statement balance: $500

- Utilization: 5%

Option 3: Request Credit Limit Increase

Increase your denominator to reduce your utilization percentage without changing your spending.

Example:

- Current limit: $5,000

- Current balance: $2,000

- Utilization: 40%

After increase:

- New limit: $10,000

- Same balance: $2,000

- New utilization: 20%

Understanding credit utilization mechanics allows you to strategically time payments for maximum credit score benefit.

Statement Balance, Payment, and Credit Score

Paying your statement balance in full every month positively impacts your credit score through multiple factors:

- Payment History (35% of FICO score): Consistent on-time statement balance payments build a perfect payment history

- Credit Utilization (30% of FICO score): Keeping balances low relative to limits

- Length of Credit History (15% of FICO score): Maintaining active accounts over time

- Credit Mix (10% of FICO score): Demonstrating responsible revolving credit management

Data Point: According to FICO, individuals with scores above 800 maintain average credit utilization below 7%.

Takeaway: Paying your statement balance protects your grace period and avoids interest. Paying your current balance (or paying early) optimizes your credit utilization for score improvement.

Pros and Cons: Statement Balance vs Current Balance Payment

Understanding the trade-offs helps you make data-driven decisions aligned with your financial goals.

Statement Balance Payment

Pros:

- Zero interest charges if paid in full by the due date

- Maintains a grace period on all purchases

- Predictable payment amount (doesn’t change after statement)

- Optimal cash flow management (you keep money longer)

- Meets contractual obligation with the issuer

- Prevents debt accumulation when paid consistently

Cons:

- Doesn’t bring balance to $0 if new purchases are posted

- May report higher utilization to credit bureaus

- Requires tracking statement date and due date

- Doesn’t account for post-statement activity

Current Balance Payment

Pros:

- Brings balance to $0 (psychological benefit)

- Maximizes available credit immediately

- May lower reported utilization if paid before the statement

- Eliminates all outstanding debt in one payment

- Simplifies tracking (no need to distinguish balances)

Cons:

- Requires more cash outlay than necessary

- Reduces float period (you pay for recent purchases sooner)

- Doesn’t provide additional interest protection beyond the statement balance

- May include pending transactions not yet posted

- Fluctuates daily (harder to plan exact payment)

Minimum Payment

Pros:

- Lowest immediate cash requirement

- Maintains account in good standing (avoids late fees)

- Preserves cash flow in emergencies

Cons:

- Triggers interest charges on the entire balance

- Loses grace period on new purchases

- Compounds debt through interest accumulation

- Extends payoff timeline to years or decades

- Costs thousands in interest over time

- Increases credit utilization (negative score impact)

- Creates a debt spiral if continued

Insight: Minimum payments are a mathematical trap. They’re designed to keep you in debt longer while maximizing issuer profit through compound interest.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Understanding the math behind Statement Balance vs Current Balance prevents costly errors.

Mistake 1: Paying Current Balance Instead of Statement Balance

Scenario:

Your statement balance is $2,000, but you made a $500 payment after the statement closed, bringing your current balance to $1,500. You pay $1,500, thinking you’re covered.

Result:

You lose your grace period because you didn’t pay the full $2,000 statement balance. Interest accrues on the original $2,000.

Solution:

Always reference your statement balance from your monthly statement, not your current balance from your app or online account.

Mistake 2: Confusing Statement Closing Date with Payment Due Date

Scenario:

Your statement closes on the 15th, but your payment is due on the 6th of the following month. You think you have until the 15th to pay.

Result:

Late payment, $40 late fee, potential credit score damage, and interest charges.

Solution:

Mark your payment due date (not statement closing date) in your calendar. Set up automatic payments for at least the statement balance to avoid this error.

Mistake 3: Assuming Partial Statement Balance Payment Means Partial Interest

Scenario:

You owe $3,000 but pay $2,900, assuming you’ll only pay interest on the $100 difference.

Result:

Interest accrues on the full $3,000 average daily balance for the entire billing cycle, not just $100.

Solution:

Understand that interest calculation is binary: full statement balance = $0 interest; anything less = interest on the full average daily balance.

Mistake 4: Ignoring the Statement Balance After Making Payments

Scenario:

You make multiple payments throughout the month totaling $2,500. Your statement balance was $3,000. You assume you’re paid in full.

Result:

You still owe $500 to meet your statement balance obligation. Failing to pay it triggers interest.

Solution:

Track your statement balance as a separate number. Subtract payments made after the statement closed to determine your remaining obligation.

Mistake 5: Paying Only Minimum to “Build Credit”

Myth:

Carrying a balance and paying interest helps build credit scores.

Reality:

This is false. Credit scores reward on-time payments and low utilization, not interest payments. Paying your statement balance in full builds credit just as effectively while costing $0 in interest.

Solution:

Pay your statement balance in full every month. Your payment history will reflect consistent on-time payments, and your utilization will remain low, both positive for your credit score.

Advanced Strategies: Optimizing Statement and Current Balance Management

For those who want to maximize both credit score benefits and cash flow efficiency, these evidence-based strategies deliver results.

Strategy 1: Multiple Payments Per Cycle

Instead of one large payment at the due date, make 2-3 smaller payments throughout the billing cycle.

Benefits:

- Keeps reported utilization lower (if payment posts before statement closes)

- Smooths cash flow requirements

- Reduces average daily balance (minimizes interest if you ever carry a balance)

Implementation:

- Payment 1: Mid-cycle (around day 15)

- Payment 2: Just before the statement closes

- Payment 3: Final payment by due date to cover any remaining statement balance

Example:

- Credit limit: $8,000

- Monthly spending: $4,000

- Statement closing date: 20th of the month

Traditional approach:

- Charges accumulate to $4,000

- Statement balance: $4,000

- Reported utilization: 50%

Multiple payment approach:

- Day 10: Pay $2,000

- Day 18: Pay $1,500

- Statement balance: $500

- Reported utilization: 6.25%

This strategy can improve your credit score by 20-40 points if you’re currently reporting high utilization[6].

Strategy 2: Statement Date Manipulation

Request your issuer to change your statement closing date to align with your cash flow.

Example:

- Current statement date: 5th of the month

- Paycheck dates: 15th and 30th

- Problem: Statement due date (26th) falls between paychecks

Solution:

- Request statement date change to 20th

- New due date: ~10th of following month

- Payment now aligns with the paycheck on the 15th

Most issuers allow statement date changes once every 12 months.

Strategy 3: Zero-Balance Reporting

For maximum credit score optimization, pay your current balance to $0 before your statement closes, then use the card minimally before the statement date.

Implementation:

- Track your statement closing date

- 2-3 days before closing, pay the current balance in full

- Let one small charge post (e.g., $5 subscription)

- Statement reports ~1% utilization

- Pay that small statement balance in full

Result:

- Reported utilization: <1%

- Account shows active (not dormant)

- Perfect payment history maintained

- Maximum credit score benefit

Data: FICO’s research shows utilization below 10% correlates with scores 20-30 points higher than 30% utilization, all else equal[7].

Strategy 4: Autopay Statement Balance with Manual Monitoring

Set up automatic payment for the full statement balance, but continue monitoring for fraud and errors.

Benefits:

- Eliminates late payment risk (35% of credit score)

- Ensures grace period protection

- Maintains cash flow (autopay triggers on due date)

- Prevents human error

Implementation:

- Set autopay to “statement balance” (not minimum or current balance)

- Link to a checking account with a sufficient buffer

- Review statements monthly for unauthorized charges

- Dispute errors before autopay triggers

This strategy removes the behavioral risk while maintaining the mathematical benefits of full statement balance payment.

💳 Which Balance Should You Pay?

Calculate the optimal payment strategy for your credit card

Pay your statement balance of $1,200 by the due date to avoid all interest charges and maintain your grace period. This saves you money while keeping your account in good standing.

📊 Financial Impact Analysis

⚠️ Warning: Paying only the minimum payment will cost you $24.99 in interest this month and extend your payoff timeline significantly. Over 12 months, you’ll pay approximately $299.88 in interest charges.

Conclusion: Mastering the Math Behind Credit Card Balances

Understanding Statement Balance vs Current Balance transforms credit cards from potential debt traps into powerful financial tools.

The math is clear and unforgiving:

- Pay your statement balance in full = $0 interest, maintained grace period, perfect payment history

- Pay less than the statement balance = interest on the entire average daily balance, lost grace period, compound debt accumulation

- Pay current balance = same interest protection as statement balance, with marginal credit utilization benefits

This isn’t about complex financial theory. It’s about understanding a simple cause-and-effect relationship that determines whether you build wealth or transfer it to credit card issuers through interest payments.

Actionable Next Steps

Immediate Actions:

- Locate your statement balance on your most recent credit card statement

- Set up autopay for the full statement balance (not minimum, not current balance)

- Mark your payment due date in your calendar with a 2-day buffer

- Check your credit utilization and aim for below 30% (ideally below 10%)

- Review your APR and consider balance transfer options if carrying high-interest debt

Long-Term Strategy:

- Track statement closing dates for all your cards to optimize utilization reporting

- Implement the 50/30/20 budgeting rule to ensure you can pay statement balances in full

- Monitor your credit score quarterly to track improvement

- Build an emergency fund to avoid carrying balances during unexpected expenses

- Understand compound interest to appreciate the true cost of minimum payments

The difference between paying your statement balance and paying the minimum can cost thousands of dollars annually in interest charges—money that could compound in investment accounts instead.

Final Insight: Credit card management is a foundational element of financial literacy. Master this simple distinction between statement and current balance, and you’ll avoid one of the most expensive mistakes in personal finance.

The math behind money rewards precision, discipline, and understanding. Apply these principles consistently, and you’ll build wealth instead of debt.

References

[1] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2023). “Credit Card Agreement Database.” CFPB.gov. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/credit-cards/agreements/

[2] Federal Reserve. (2009). “Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009.” FederalReserve.gov. https://www.federalreserve.gov/creditcard/

[3] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. (2024). “Credit Card Grace Periods.” OCC.gov. https://www.occ.gov/topics/consumers-and-communities/consumer-protection/credit-cards/index-credit-cards.html

[4] FICO. (2025). “What’s in my FICO Scores?” MyFICO.com. https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/whats-in-your-credit-score

[5] FICO. (2024). “Credit Utilization and Credit Scores.” FICO.com. https://www.fico.com/blogs/credit-utilization-rate

[6] Experian. (2024). “How to Improve Your Credit Score.” Experian.com. https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/credit-education/improving-credit/improve-credit-score/

[7] VantageScore. (2025). “Credit Utilization Impact on Credit Scores.” VantageScore.com. https://www.vantagescore.com/

[8] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2024). “What is a credit utilization rate?” CFPB.gov. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-a-credit-utilization-rate-en-1597/

About the Author

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform dedicated to teaching the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and risk management. With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based education, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable frameworks that empower readers to make informed decisions with their money.

Max’s approach combines rigorous quantitative analysis with accessible teaching, helping thousands of readers understand the cause-and-effect relationships that determine financial outcomes. His work focuses on demonstrating how mathematical literacy—understanding compound interest, valuation principles, credit mechanics, and risk assessment- creates the foundation for long-term wealth accumulation.

Through The Rich Guy Math, Max provides comprehensive guides on investing fundamentals, credit optimization, budgeting strategies, and financial planning, all grounded in data, formulas, and real-world examples.

Educational Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. The information presented represents general principles and mathematical frameworks related to credit card balance management and should not be considered personalized recommendations.

Credit card terms, interest rates, grace periods, and policies vary significantly by issuer, card type, and individual creditworthiness. Readers should review their specific credit card agreements and statements to understand the exact terms applicable to their accounts.

While this content is based on authoritative sources and current industry practices as of 2025, credit card regulations, issuer policies, and financial best practices may change over time. Readers should verify current information with their credit card issuers and consult qualified financial professionals for personalized advice tailored to their specific circumstances.

The Rich Guy Math and its authors make no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or suitability of this information for any particular purpose. Readers assume full responsibility for their financial decisions and should conduct independent research and due diligence before taking action based on this content.

Past performance and historical examples do not guarantee future results. Individual financial outcomes depend on numerous factors, including but not limited to income, expenses, credit history, spending patterns, and economic conditions.

For specific questions about your credit card accounts, payment obligations, or credit management strategies, consult directly with your card issuer or a qualified financial advisor.

Statement Balance vs Current Balance: FAQs

What happens if I pay more than my statement balance?

Paying more than your statement balance creates a credit balance (negative balance) on your account. This credit applies to future purchases automatically, or you can request a refund.

Example:

Statement balance: $1,000

You pay: $1,200

Result: -$200 credit balance

Next purchase of $50 → new current balance: -$150

There is no benefit to maintaining a credit balance unless you’re planning large purchases and want to reduce utilization reporting.

Can I pay my current balance before the statement closes?

Yes. Paying your current balance before the statement closing date reduces the balance reported to credit bureaus, lowering utilization.

Strategy:

Current balance: $3,000

Pay $2,500 before statement closes

Statement balance: $500

Reported utilization: much lower

Pay remaining $500 by due date

Does paying my current balance improve my credit score faster?

Not directly. Scores respond to reported balances (usually the statement balance) and payment history.

Paying current balance only helps if you do it before the statement closes so the lower balance is reported.

Timing matters more than amount.

What if my current balance is lower than my statement balance?

This happens when you make payments or credits after the statement closes. You still owe the full statement balance to avoid interest.

Example:

Statement balance: $2,000

Payment after statement: -$500

Current balance: $1,500

Amount to pay: still $2,000

How do I find my statement balance vs current balance?

Statement Balance:

• Monthly statement PDF or paper

• Email notification

• “Statements” section online

Current Balance:

• Dashboard or app home screen

• Updates in real-time

Will paying only the minimum payment hurt my credit score?

Indirectly, yes. Minimum payments increase balances through interest, raising utilization ratios, which can lower scores.

Does my statement balance include pending transactions?

No. Pending transactions appear in the current balance but are not included in the statement balance until they post.

Example:

Statement closes: June 15

Purchase June 14: $100 pending

Posts June 16 → included on next statement

Can I avoid interest by paying my current balance instead of statement balance?

No. You must pay the full statement balance to avoid interest, even if your current balance is lower.

What’s the grace period, and how does it relate to statement balance?

The grace period is the interest-free window between statement closing and the payment due date. You maintain it only by paying the full statement balance every month.

Should I pay my statement balance or current balance to build credit?

Pay your full statement balance every month. This builds payment history, keeps utilization low, costs $0 in interest, and preserves your grace period.