← Back to Budgeting and Saving

Every month, millions of Americans wonder where their paycheck went. The money arrives, bills get paid, groceries are purchased, and somehow, nothing remains for savings or investing. The problem isn’t income; it’s the absence of intentional allocation.

Zero-based budgeting solves this by assigning every single dollar a specific job before the month begins. Unlike traditional budgeting methods that adjust last month’s numbers, zero-based budgeting starts from scratch each cycle, forcing deliberate decisions about where money flows. The formula is elegantly simple: Income – Expenses = $0.

This methodology, originally developed by Pete Pyhrr at Texas Instruments in the 1970s, has helped corporations save billions and individuals build wealth systematically. When 91% of companies using zero-based budgeting meet or exceed their financial targets, the data-driven evidence becomes clear: intentional allocation outperforms passive spending every time.

This guide breaks down the math behind zero-based budgeting, demonstrates the step-by-step implementation process, and reveals when this approach accelerates wealth building and when it doesn’t.

Key Takeaways

Zero-based budgeting assigns every dollar of income a specific purpose before the month begins, creating Income – Expenses = $0

The method eliminates “leftover money” syndrome by forcing intentional decisions about savings, debt repayment, and discretionary spending.

Corporate data shows 91% of organizations using ZBB meet financial targets, with large companies saving up to $1 billion annually.

Personal implementation requires five monthly steps: list income, assign categories, track spending, adjust mid-month, and reset for the next cycle.

Zero-based budgeting works best for active planners with predictable income; variable earners may benefit more from percentage-based methods like the 50/30/20 rule.

What Is Zero-Based Budgeting?

Zero-based budgeting is a financial allocation method where every dollar of income receives a specific assignment before spending begins. The goal is mathematical precision: Income – All Allocated Expenses = $0.

The “zero” doesn’t mean zero money in the bank. It means zero unassigned dollars floating without purpose.

Traditional budgeting typically starts with last month’s numbers and adjusts incrementally, adding 3% here and cutting 5% there. Zero-based budgeting rejects this historical bias entirely. Each budgeting cycle begins from a blank slate, requiring justification for every expense category regardless of previous spending patterns.

The Core Formula

Total Monthly Income – (Fixed Expenses + Variable Expenses + Savings + Debt Payments) = $0

If income is $5,000, then $5,000 must be allocated across rent, groceries, utilities, emergency fund contributions, retirement investing, and every other category until nothing remains unassigned.

This approach forces trade-offs. Choosing to allocate $200 to dining out means $200 less for other categories. The scarcity becomes visible, creating accountability that percentage-based budgets often lack.

Why “Zero” Matters

The psychological shift is significant. When $347 sits unallocated in a checking account, it feels like “extra” money available for impulse purchases. When that same $347 is pre-assigned to a sinking fund for car maintenance, spending it requires consciously stealing from a future need.

Zero-based budgeting transforms abstract financial goals into concrete monthly decisions. Instead of “I should save more,” the budget forces the question: “How much am I saving this month, and from which categories will I reduce spending to make it happen?”

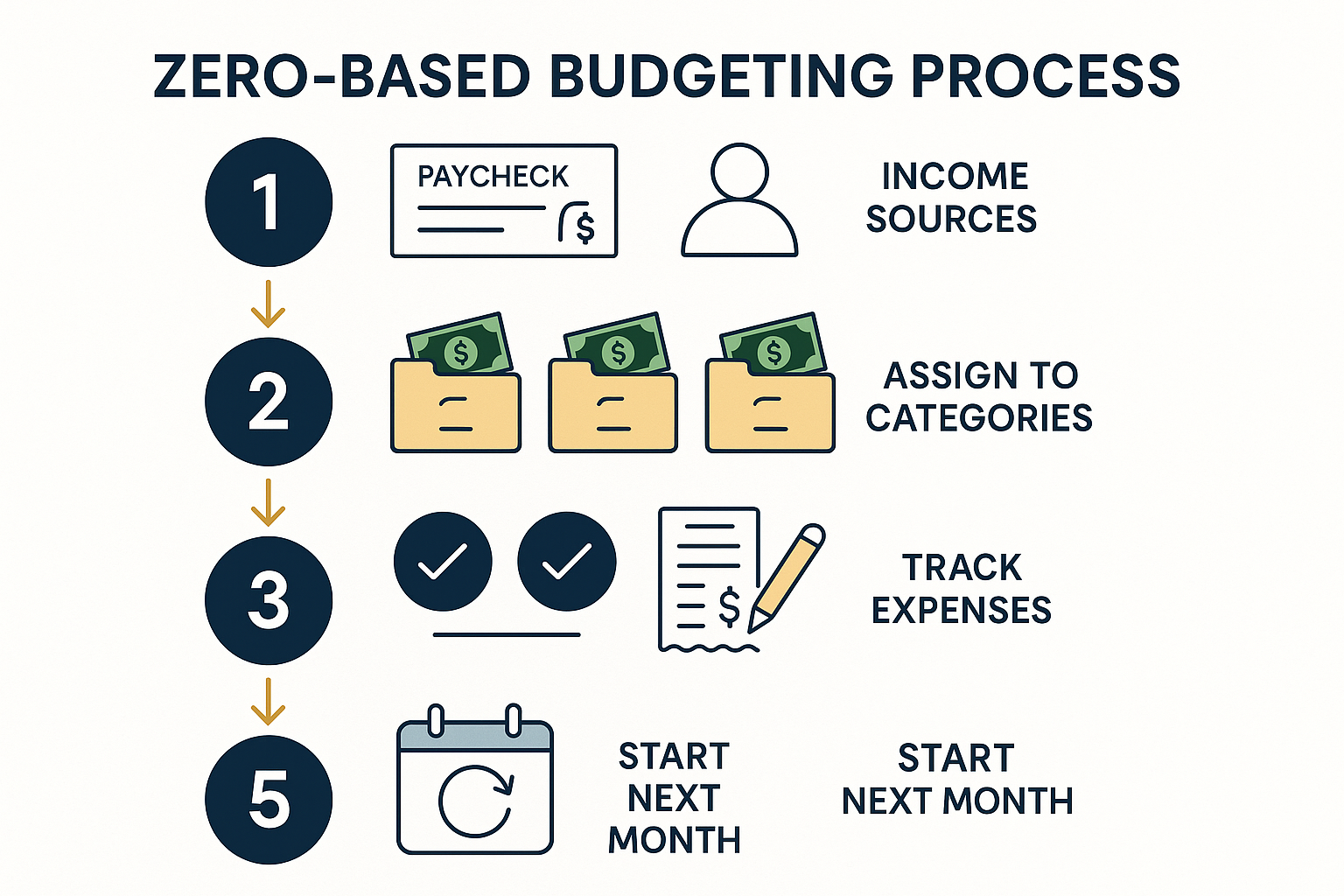

How Zero-Based Budgeting Works (5 Simple Steps)

Implementation follows a repeatable five-step cycle executed monthly. Each step builds upon the previous one, creating a comprehensive financial allocation system.

Step 1 — List All Income Sources

Begin with total monthly income after taxes. Include:

- Primary salary or wages (net pay after deductions)

- Side income (freelance, gig work, rental income)

- Passive income (dividends, interest, royalties)

- Variable bonuses (commissions, performance pay)

For variable income earners, use the lowest expected monthly amount as the baseline. Bonus income received later gets allocated when it arrives, not before.

Example:

- Net salary: $4,200

- Freelance income: $600

- Dividend income: $75

- Total Monthly Income: $4,875

Step 2 — Assign Every Dollar a Job

Create spending categories and allocate specific amounts to each until the total equals the monthly income. Essential categories include:

Fixed Expenses:

- Housing (rent/mortgage, insurance, property tax)

- Utilities (electric, water, gas, internet)

- Transportation (car payment, insurance, gas)

- Debt payments (student loans, credit cards)

Variable Expenses:

- Groceries

- Dining out

- Entertainment

- Personal care

- Clothing

Savings & Investing:

- Emergency fund contributions

- Retirement accounts (401k, IRA)

- Taxable investment accounts

- Compound interest growth vehicles

Sinking Funds:

- Car maintenance/replacement

- Annual insurance premiums

- Holiday gifts

- Home repairs

Allocate until Income – Total Allocations = $0. If $150 remains unassigned, decide immediately: Does it fund the emergency fund, accelerate debt payoff, or increase investment contributions?

Step 3 — Track Spending Throughout the Month

Zero-based budgeting requires active monitoring. As expenses occur, record them against allocated categories:

- Manual tracking: Write purchases in a budget notebook or spreadsheet

- Digital tracking: Use apps like YNAB (You Need A Budget) or Goodbudget

- Hybrid approach: Review bank transactions weekly and categorize manually

The tracking reveals overspending immediately. If the grocery allocation is $600 and spending reaches $580 by day 20, only $20 remains for the final ten days. This real-time feedback prevents the month-end surprise of overdraft fees.

Step 4 — Adjust Mid-Month as Needed

Life rarely follows the budget perfectly. The car needs an unexpected $200 repair. A friend’s wedding requires a $150 gift.

Zero-based budgeting accommodates changes through reallocation. The budget isn’t rigid; it’s intentional. When unplanned expenses arise, reduce other categories to maintain the zero balance:

Example Adjustment:

- Unexpected car repair: +$200

- Reduce dining out: -$100

- Reduce entertainment: -$50

- Reduce clothing budget: -$50

- Net change: $0

The discipline isn’t avoiding adjustments; it’s making conscious trade-offs rather than defaulting to credit cards.

Step 5 — Reset for the Next Month

On the last day of the month, the cycle restarts. Income may change. Expenses will vary. Priorities shift.

Create a fresh budget from zero, using the previous month’s data as information, not as a template. If August required $800 for groceries but September has fewer dinner parties planned, allocate $650 and redirect $150 elsewhere.

This monthly reset prevents the “status quo” trap where spending continues simply because “it was this much last quarter”. Each cycle forces renewed justification for every allocation.

Zero-Based Budget Categories

Effective zero-based budgets organize spending into clear categories with specific allocations. The structure creates accountability and reveals spending patterns over time.

Essential Category Framework

| Category | Typical Allocation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Housing | 25-35% of income | Rent/mortgage, property tax, homeowners insurance, HOA fees |

| Utilities | 5-10% of income | Electric, gas, water, internet, phone, streaming services |

| Transportation | 10-20% of income | Car payment, insurance, gas, maintenance, public transit |

| Groceries | 10-15% of income | Food, household supplies, personal care items |

| Debt Payments | 5-20% of income | Credit cards, student loans, personal loans (minimum + extra) |

| Savings | 10-20% of income | Emergency fund, retirement contributions, taxable investments |

| Sinking Funds | 5-10% of income | Car replacement, annual insurance, home repairs, gifts |

| Discretionary | 5-15% of income | Dining out, entertainment, hobbies, clothing, subscriptions |

These percentages serve as starting points, not rigid rules. A household with a paid-off home might allocate 10% to housing and 30% to investments. Someone following the 4% rule for retirement planning will prioritize savings differently from someone focused on debt elimination.

Sinking Funds: The Hidden Power Category

Sinking funds prevent “unexpected” expenses from derailing budgets. These are predictable costs that don’t occur monthly:

- Car insurance: $1,200 annual premium ÷ 12 months = $100/month allocation

- Holiday gifts: $600 annual spending ÷ 12 months = $50/month allocation

- Home maintenance: $1,800 annual reserve ÷ 12 months = $150/month allocation

By allocating monthly toward these known future expenses, the budget remains stable when bills arrive. The $1,200 insurance premium doesn’t create a crisis; it’s already funded.

This approach mirrors corporate capital allocation strategies, where cash flow management requires planning for irregular but predictable expenses.

Income-Based Category Adjustments

Budget allocations scale with income, but not proportionally. As income rises, the percentage allocated to necessities typically decreases while savings and investing increase:

$3,000/month income:

- Housing: 33% ($1,000)

- Savings: 10% ($300)

$8,000/month income:

- Housing: 19% ($1,500)

- Savings: 25% ($2,000)

This scaling effect accelerates wealth building for higher earners, assuming lifestyle inflation remains controlled. The math behind money reveals that the gap between earning and spending, not absolute income, determines wealth accumulation velocity.

Zero-Based Budget Example (Spreadsheet + Envelope System)

Theory becomes practical through concrete examples. This section demonstrates a complete zero-based budget for a household earning $4,875 monthly.

Sample Monthly Budget

Total Monthly Income: $4,875

Fixed Expenses:

- Rent: $1,350

- Car payment: $285

- Car insurance: $125

- Renters insurance: $25

- Internet: $65

- Phone: $80

- Student loan payment: $200

- Fixed Total: $2,130

Variable Expenses:

- Groceries: $550

- Gas: $180

- Dining out: $200

- Entertainment: $100

- Personal care: $60

- Clothing: $80

- Miscellaneous: $75

- Variable Total: $1,245

Savings & Debt:

- Emergency fund: $400

- Roth IRA contribution: $500

- Extra student loan payment: $150

- Savings Total: $1,050

Sinking Funds:

- Car maintenance fund: $100

- Annual insurance fund: $100

- Holiday/gifts fund: $100

- Home/furniture fund: $50

- Sinking Total: $350

Budget Check:

$2,130 + $1,245 + $1,050 + $350 = $4,875 ✓

Income – Allocations = $4,875 – $4,875 = $0 ✓

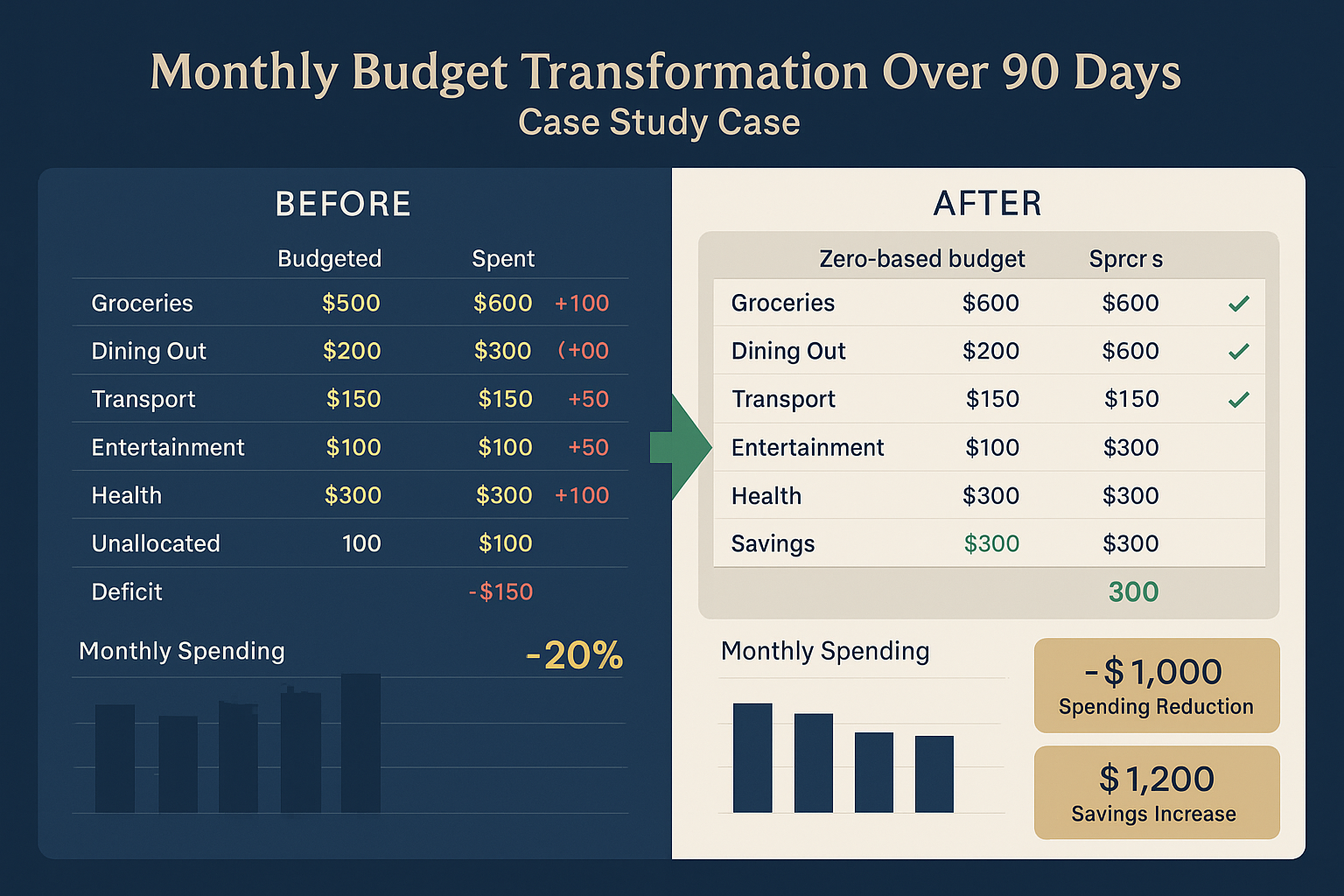

Before vs. After: The Transformation

Before Zero-Based Budgeting:

- Monthly income: $4,875

- Tracked expenses: ~$4,200

- “Leftover” money: ~$675

- Actual savings: $0 (spent on untracked purchases)

- Credit card balance: Growing by $200/month

After Zero-Based Budgeting:

- Monthly income: $4,875

- Allocated expenses: $4,875

- Unallocated money: $0

- Actual savings: $1,050/month ($400 emergency + $500 retirement + $150 debt acceleration)

- Credit card balance: Decreasing by $150/month

The difference isn’t income; it’s intentional allocation. The “missing” $675 was always spent; zero-based budgeting simply made those decisions conscious and redirected funds toward wealth building.

Implementation Methods

Digital Spreadsheet Approach:

Create a simple spreadsheet with columns for:

- Category name

- Budgeted amount

- Actual spending

- Remaining balance

- Difference (budget vs. actual)

Update the “actual spending” column as transactions occur. The “remaining balance” shows real-time category availability, preventing overspending.

Envelope System (Cash-Based):

For variable categories prone to overspending:

- Withdraw cash equal to category allocations

- Place cash in labeled envelopes (Groceries, Dining Out, Entertainment)

- Spend only from designated envelopes

- When an envelope empties, spending stops

The physical limitation of cash creates powerful psychological friction against overspending. When the dining out envelope holds $40 with ten days remaining, the trade-off becomes tangible.

Many practitioners combine methods: digital tracking for fixed expenses and automatic savings, cash envelopes for discretionary categories.

Pros and Cons of Zero-Based Budgeting

No financial methodology suits every situation. Zero-based budgeting delivers specific advantages while creating distinct challenges.

Advantages: Why Zero-Based Budgeting Works

Eliminates Waste Through Visibility

Every dollar receives scrutiny. Subscriptions that auto-renew unnoticed become obvious when allocating funds monthly. The $14.99 streaming service used twice last quarter faces justification: Does this provide $180 annual value?

Corporate implementations demonstrate this effect dramatically. Organizations using zero-based budgeting achieve savings up to $1 billion by eliminating expenses that continued simply because they existed previously[1].

Accelerates Savings and Debt Reduction

By forcing explicit allocation to savings and debt categories, zero-based budgeting prevents the “save what’s left” trap. When $500 is allocated to retirement investing on day one, it’s not available for discretionary spending. The savings happen automatically.

This mirrors dollar-cost averaging principles: consistent, predetermined investing outperforms sporadic contributions based on leftover funds.

Creates Accountability and Awareness

Tracking spending against predetermined categories reveals actual behavior patterns. The person who believes they spend $300 monthly on groceries discovers actual spending is $475. This data-driven insight enables informed adjustments.

The accountability extends to shared finances. When couples budget together using zero-based allocation, both parties understand where money flows and why. Disagreements shift from “you spent too much” to “should we reallocate from dining out to entertainment?”

Aligns Spending with Values and Goals

Zero-based budgeting forces priority ranking. When income is finite, and every dollar requires assignment, spending naturally gravitates toward what matters most.

Someone valuing travel over dining out allocates accordingly. The budget becomes a monthly referendum on values, ensuring spending matches stated priorities rather than defaulting to convenience.

Disadvantages: When Zero-Based Budgeting Fails

Time-Intensive Monthly Process

Creating a budget from scratch monthly requires 2-4 hours of focused work. Tracking expenses demands daily or weekly attention. For busy professionals or parents, this time commitment becomes unsustainable.

The exhaustive analysis required, evaluating the necessity and efficacy of every operational expense, creates decision fatigue when applied to personal finance.

Emotional and Mental Fatigue

Constant spending awareness can feel restrictive. Every purchase requires category checking. Every adjustment demands reallocation decisions. This cognitive load exhausts some practitioners, leading to budget abandonment.

The psychological burden intensifies for those with scarcity mindsets or anxiety around money. Instead of creating freedom through clarity, the method can amplify stress.

Difficult with Variable Income

Freelancers, commission-based earners, and seasonal workers face challenges when income fluctuates monthly. Zero-based budgeting requires knowing total income before allocation, difficult when paychecks vary by 30-50%.

These earners often benefit more from percentage-based methods like the 50/30/20 rule, which adapts automatically to income changes.

Requires Discipline and Consistency

Zero-based budgeting fails without follow-through. Creating a perfect budget means nothing if spending goes untracked and categories are ignored. The method demands behavioral consistency that not everyone maintains.

Unlike automated systems that function passively, zero-based budgeting requires active participation every single day.

Zero-Based Budgeting vs 50/30/20 Rule

Both methods aim to control spending and increase savings, but they approach allocation differently. Understanding the distinctions reveals which method fits specific situations.

Methodology Comparison

| Aspect | Zero-Based Budgeting | 50/30/20 Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Allocation Method | Every dollar assigned to specific categories | Income divided into three broad buckets |

| Granularity | High (10-20+ categories) | Low (3 categories) |

| Time Required | 2-4 hours monthly + daily tracking | 30 minutes monthly + weekly check-ins |

| Flexibility | High (adjust any category) | Moderate (adjust within buckets) |

| Best For | Detail-oriented planners, debt elimination | Busy professionals, budgeting beginners |

| Income Variability | Difficult with fluctuating income | Adapts automatically to income changes |

| Savings Rate | Customizable (typically 15-30%) | Fixed at 20% minimum |

When to Choose Zero-Based Budgeting

Ideal Situations:

- Aggressive debt payoff: Allocating every dollar maximizes debt payments while maintaining essential expenses

- Significant savings goals: Saving for a home down payment or early retirement requires precise allocation

- Spending awareness needed: Those who consistently overspend benefit from category-level tracking

- Stable income: Predictable paychecks make monthly planning straightforward

Example: Someone earning $5,000 monthly with $25,000 in credit card debt might allocate $1,500 to debt payments, $2,800 to necessities, $400 to emergency fund building, and $300 to minimal discretionary spending. This precision accelerates debt elimination faster than percentage-based methods.

When to Choose 50/30/20

Ideal Situations:

- Variable income: Freelancers apply percentages regardless of monthly earnings

- Budgeting fatigue: Those who abandoned detailed budgets benefit from simplicity

- Stable financial situation: People without debt or major savings goals maintain wealth with less effort

- Time constraints: Busy professionals need functional budgets without extensive tracking

Example: A freelancer earning between $4,000-$7,000 monthly allocates 50% to needs, 30% to wants, and 20% to savings regardless of exact income. When earnings hit $7,000, savings automatically increase to $1,400 without budget recalculation. www.investopedia.com

Hybrid Approach: Best of Both Methods

Many practitioners combine strategies:

- Use 50/30/20 percentages as an initial allocation framework

- Apply zero-based budgeting within the 30% “wants” category

- Track necessities and savings at the bucket level, not line-item detail

This hybrid reduces time commitment while maintaining intentional allocation for discretionary spending, the category most prone to waste.

Understanding personal financial behavior determines the optimal method. The best budget is the one actually used consistently, not the theoretically perfect system abandoned after two months.

Is Zero-Based Budgeting Right for You?

Self-assessment reveals whether zero-based budgeting aligns with financial situation, personality, and goals.

Personality and Behavioral Fit

You’ll likely succeed with zero-based budgeting if you:

Enjoy detailed planning and organization

Feel motivated by tracking progress toward specific metrics

Have 30+ minutes weekly for budget maintenance

Experience satisfaction from optimizing systems

Prefer concrete rules over general guidelines

You’ll likely struggle with zero-based budgeting if you:

Find detailed tracking tedious or stressful

Prefer spontaneity in spending decisions

Have limited time for financial management

Experience anxiety from constant money awareness

Work better with simple, automated systems

Financial Situation Assessment

Zero-based budgeting works best when:

- Income is predictable: Salary-based compensation with minimal monthly variation

- Debt exists: Specific payoff targets benefit from precise allocation

- Savings goals are aggressive: Targeting 25-40% savings rates requires detailed planning

- Spending exceeds income: Identifying cuts demands category-level visibility

- Financial transition is occurring: Job changes, marriage, or home purchases need careful planning

Alternative methods work better when:

- Income fluctuates significantly: Commission, freelance, or seasonal work

- Financial situation is stable: No debt, adequate emergency fund, consistent savings

- Time is extremely limited: Working multiple jobs or caring for dependents

- Automation handles most finances: Direct deposit to savings and investments is already functioning

Trial Period Recommendation

Rather than committing indefinitely, test zero-based budgeting for three months:

Month 1: Learn the system, expect imperfection, focus on tracking accuracy

Month 2: Refine categories, adjust allocations, identify problem areas

Month 3: Evaluate sustainability, does this feel manageable or exhausting?

After 90 days, the data reveals whether zero-based budgeting improves financial outcomes enough to justify the time investment. If savings increase by $400 monthly but the process creates significant stress, consider hybrid approaches or percentage-based alternatives.

The goal isn’t budget perfection; it’s sustainable wealth building through intentional allocation.

Tools and Apps for Zero-Based Budgeting

Technology reduces the time burden of zero-based budgeting while maintaining allocation precision. The right tool depends on technical comfort, budget complexity, and preferred tracking method.

YNAB (You Need A Budget)

Cost: $14.99/month or $99/year

Platform: Web, iOS, Android

YNAB was designed specifically for zero-based budgeting. The software enforces the “give every dollar a job” philosophy through its interface.

Key Features:

- Real-time category balances showing exactly what’s available

- Automatic bank syncing for transaction imports

- Goal tracking for savings targets and debt payoff

- Reporting showing spending trends over time

- Mobile apps for on-the-go budget checking

Best For: Those committed to zero-based budgeting who value automated tracking and detailed reporting.

Limitation: Monthly cost may feel ironic when budgeting to save money. However, users typically save $600+ monthly[4], making the $15 fee a 40:1 return.

Goodbudget

Cost: Free (limited envelopes) or $8/month (unlimited)

Platform: Web, iOS, Android

Goodbudget digitizes the envelope system without requiring cash. Users create virtual envelopes for each category and allocate funds accordingly.

Key Features:

- Envelope-based allocation matching a zero-based philosophy

- Shared budgets for couples or families

- Debt payoff tracking with progress visualization

- No bank syncing (manual entry only)

Best For: Those who want envelope-system psychology without carrying cash, or couples managing finances together.

Limitation: Manual transaction entry increases time commitment but improves spending awareness.

Excel or Google Sheets

Cost: Free (Google Sheets) or $70/year (Microsoft 365)

Platform: Web, desktop, mobile

Spreadsheets offer complete customization for those comfortable with formulas and formatting.

Template Structure:

- The income section lists all sources

- Category rows with budgeted amounts

- Actual spending column updated manually

- Remaining balance calculated automatically:

=Budgeted-Actual - Summary showing total allocated vs. income

Best For: Spreadsheet-comfortable users who want complete control and no subscription fees.

Limitation: No automatic bank syncing; requires manual data entry and formula setup.

Pen and Paper (Traditional Method)

Cost: $5 for a notebook

Platform: Physical

The original zero-based budgeting method remains effective. Write categories, allocate amounts, and track spending manually.

Best For: Those who process information better through writing, or who want to avoid screen time.

Limitation: No automatic calculations; math errors possible; no digital backup.

Cash Envelope System

Cost: Free (using existing envelopes)

Platform: Physical cash

For variable categories, physical cash creates powerful spending friction.

Implementation:

- Identify discretionary categories (groceries, dining out, entertainment)

- Withdraw allocated cash monthly

- Distribute into labeled envelopes

- Spend only from designated envelopes

- When empty, spending stops

Best For: Those who overspend on credit/debit cards but control spending better with physical cash.

Limitation: Inconvenient for online purchases; security concerns about carrying large cash amounts.

Hybrid Approach

Many successful practitioners combine tools:

- YNAB or Goodbudget for fixed expenses and savings tracking

- Cash envelopes for groceries, dining, and entertainment

- Spreadsheet for monthly planning and annual review

The optimal system balances automation (reducing time) with awareness (maintaining accountability).

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Common errors undermine zero-based budgeting effectiveness. Recognizing these pitfalls before they occur increases success probability.

Forgetting Irregular Expenses

The Mistake: Budgeting only for monthly bills while ignoring quarterly, semi-annual, or annual expenses.

The Consequence: The $600 car insurance bill arrives and derails the entire budget, forcing credit card debt or savings withdrawals.

The Solution: Create sinking fund categories for all irregular expenses:

- Annual insurance premiums

- Vehicle registration

- Holiday gifts

- Birthday presents

- Home/car maintenance

- Professional dues or subscriptions

Calculate the annual cost, divide by 12, and allocate monthly. A $1,200 annual expense requires $100 monthly allocation.

Creating No Buffer Category

The Mistake: Allocating every dollar to specific categories with zero flexibility for unexpected needs.

The Consequence: A $40 prescription copay or $25 school field trip permission slip has no category, forcing budget-breaking decisions.

The Solution: Include a “miscellaneous” or “buffer” category of $50-100 monthly for truly unpredictable small expenses. This isn’t permission for impulse purchases—it’s acknowledgment that perfect prediction is impossible.

Setting Unrealistic Category Amounts

The Mistake: Allocating $300 to groceries when actual spending is consistently $500, hoping willpower will bridge the gap.

The Consequence: Overspending by day 15, budget abandonment, and return to untracked spending.

The Solution: Use actual spending data from the previous 2-3 months as the baseline. If groceries averaged $475, start there. Reduce gradually through intentional strategies (meal planning, generic brands), not through wishful thinking.

Giving Up After One Bad Month

The Mistake: Overspending in week two, deciding “zero-based budgeting doesn’t work for me,” abandoning the system.

The Consequence: Returning to unconscious spending patterns that created the original problem.

The Solution: Expect imperfection for the first 2-3 months. Zero-based budgeting is a skill that improves with practice. Each month reveals better category estimates and spending patterns. Persistence matters more than perfection.

Ignoring the Budget After Creating It

The Mistake: Spending hours building a detailed budget, then never checking category balances or tracking expenses.

The Consequence: The budget becomes decorative rather than functional, providing zero behavior change.

The Solution: Schedule specific tracking times:

- Daily: 5 minutes reviewing transactions (morning coffee routine)

- Weekly: 15 minutes categorizing expenses and checking balances (Sunday evening)

- Monthly: 60 minutes creating next month’s budget (last day of current month)

Consistency transforms the budget from a document into a decision-making tool.

Not Adjusting for Life Changes

The Mistake: Using the same budget month after month despite income changes, new expenses, or completed goals.

The Consequence: The budget becomes increasingly disconnected from reality, reducing its usefulness.

The Solution: Rebuild from zero each month. Got a raise? Reallocate the increase intentionally. Paid off a car? Redirect that payment to investments or other debt. Moved to a new apartment? Adjust housing and utility allocations.

The “zero-based” philosophy means starting fresh each cycle, not copying last month’s numbers indefinitely.

Case Study: $300/Month Saved in 90 Days

Theory becomes concrete through real implementation. This case study demonstrates zero-based budgeting’s impact on actual household finances.

The Starting Situation

Household Profile:

- Combined income: $6,200/month (after taxes)

- Credit card debt: $8,500

- Emergency savings: $1,200

- Retirement contributions: $250/month (employer match only)

- Financial stress: High

Pre-Budget Spending Pattern:

- Tracked expenses: ~$5,400/month

- “Leftover” money: ~$800/month

- Actual savings: $0 (spent on untracked purchases and small credit card payments)

- Net worth change: Negative (credit card interest exceeded savings)

Month 1: Implementation and Discovery

Budget Created:

| Category | Allocation |

|---|---|

| Rent | $1,650 |

| Utilities | $180 |

| Car payments | $420 |

| Insurance (car + renters) | $185 |

| Minimum debt payments | $180 |

| Groceries | $600 |

| Gas | $220 |

| Dining out | $400 |

| Entertainment | $200 |

| Personal care | $120 |

| Miscellaneous | $100 |

| Emergency fund | $300 |

| Extra debt payment | $200 |

| Retirement (additional) | $250 |

| Sinking funds | $195 |

| Total | $6,200 |

Month 1 Results:

- Grocery overspending: $125 (actual: $725)

- Dining out overspending: $85 (actual: $485)

- Entertainment underspending: $60 (actual: $140)

- Net overspending: $150

Key Discovery: Untracked dining expenses (coffee shops, lunch near work, weekend brunches) consumed $485 monthly, $85 over budget, and $185 more than pre-budget estimates.

Month 2: Adjustment and Optimization

Budget Adjustments:

- Increased grocery allocation to $650 (meal planning reduced dining out need)

- Reduced dining out to $300 (packed lunches, limited to 2 restaurant meals weekly)

- Reduced entertainment to $150 (free activities, library instead of bookstore)

- Increased the emergency fund to $350

- Increased extra debt payment to $250

New Strategies Implemented:

- Meal planning every Sunday

- Packed lunch 4 days weekly

- Cash envelope for dining out ($300 withdrawn, no debit card usage)

- Canceled $45 in unused subscriptions

Month 2 Results:

- Stayed within budget in 11 of 13 categories

- Saved $350 in the emergency fund

- Paid $430 total toward credit card debt ($180 minimum + $250 extra)

- Total saved/debt reduction: $780

Month 3: Optimization and Momentum

Additional Refinements:

- Reduced grocery budget to $625 (meal planning efficiency improved)

- Maintained $300 dining out (sustainable level)

- Increased retirement contribution to $300

- Increased the extra debt payment to $300

Month 3 Results:

- Perfect budget adherence (stayed within all categories)

- Emergency fund contribution: $350

- Debt payment: $480 ($180 minimum + $300 extra)

- Retirement: $300

- Total saved/debt reduction: $1,130

90-Day Transformation Summary

Before Zero-Based Budgeting:

- Monthly savings: $0

- Monthly debt reduction: ~$50 (minimum payments minus interest)

- Emergency fund: $1,200

- Credit card balance: $8,500

- Financial awareness: Low

After 90 Days:

- Average monthly savings: $350

- Average monthly debt reduction: $430

- Emergency fund: $2,250 (+$1,050)

- Credit card balance: $7,210 (-$1,290)

- Financial awareness: High

Total Financial Improvement: $2,340 in 90 days

The household didn’t receive a raise or windfall. Income remained constant at $6,200 monthly. The entire improvement came from intentional allocation and spending awareness.

Key Success Factors

- Tracking revealed hidden spending: The $485 monthly dining habit was invisible before budgeting.

- Gradual adjustments beat perfection: Month 1 overspending didn’t derail the process.

- Cash envelopes controlled problem categories: Physical limits prevented dining out and overspending

- Subscription audit recovered $45 monthly: Unused services identified and canceled.

- Meal planning reduced both groceries and dining out: Efficiency improved over time.

This case demonstrates zero-based budgeting’s core value: transforming unconscious spending into intentional allocation, redirecting hundreds of dollars monthly toward wealth building without income changes.

💰 Zero-Based Budget Calculator

Assign every dollar a job until Income – Expenses = $0

Conclusion

Zero-based budgeting transforms financial management from passive observation to active allocation. By assigning every dollar a specific job before the month begins, the method eliminates the “where did my money go?” question that plagues unconscious spenders.

The formula, Income – Expenses = $0, creates mathematical precision that percentage-based budgets can’t match. When 91% of organizations using zero-based budgeting meet their financial targets, the evidence supports the methodology’s effectiveness.

Implementation requires commitment: 2-4 hours monthly for budget creation, daily expense tracking, and willingness to make trade-offs between competing priorities. Those who maintain consistency discover hundreds of dollars monthly redirected from unconscious spending toward intentional wealth building. www.sec.gov

The method works best for detail-oriented individuals with predictable income and specific financial goals, aggressive debt payoff, large savings targets, or spending awareness development. Variable income earners or those seeking simplicity may benefit more from the 50/30/20 rule or hybrid approaches.

Success doesn’t require perfection. The first month reveals spending patterns. The second month refines allocations. The third month builds sustainable habits. Each cycle improves accuracy and reduces time investment as categories stabilize.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Calculate total monthly income (after taxes, all sources)

- List current expenses by category using last month’s bank statements

- Create the first zero-based budget using the five-step process outlined above

- Choose tracking method (app, spreadsheet, or cash envelopes)

- Schedule weekly budget reviews (15 minutes, same day/time each week)

- Commit to a 90-day trial before evaluating effectiveness

The math behind money is simple: wealth accumulates when income exceeds expenses, and the gap is invested for compound growth. Zero-based budgeting maximizes that gap through intentional allocation rather than hoping money remains at month’s end.

Financial freedom doesn’t require a higher income; it requires conscious control over the income already earned. Zero-based budgeting provides the framework for that control.

References

[1] Corporate zero-based budgeting effectiveness data: Financial planning industry research on ZBB implementation outcomes and cost savings in large organizations, 2023-2025.

[2] Nonprofit financial management studies: Analysis of zero-based budgeting applications in mission-driven organizations and resource allocation optimization.

[3] Pyhrr, P. “Zero-Based Budgeting: A Practical Management Tool for Evaluating Expenses.” Texas Instruments internal methodology documentation, 1970s; later adapted for corporate and personal finance applications.

[4] Personal finance budgeting methodology research: Consumer financial behavior studies examining 50/30/20 rule implementation and zero-based budgeting adoption rates.

[5] YNAB user outcome data: Self-reported savings improvements from You Need A Budget software users, 2024-2025.

[6] Personal zero-based budgeting implementation studies: Financial literacy research on individual and household budget allocation strategies and wealth-building outcomes.

Educational Disclaimer

This article provides educational information about zero-based budgeting methodology and financial planning concepts. It is not personalized financial advice.

Individual financial situations vary significantly based on income, expenses, debt levels, savings goals, risk tolerance, and life circumstances. What works optimally for one household may be inappropriate for another.

Before implementing significant changes to budgeting methods, spending patterns, or financial strategies, consider consulting with a qualified financial advisor who can evaluate your specific situation and provide personalized recommendations.

The case studies and examples presented represent specific scenarios and outcomes. Individual results will vary based on income levels, spending discipline, category allocations, and consistency of implementation.

Zero-based budgeting requires time commitment and behavioral consistency. Those with limited time, variable income, or high financial stress should carefully evaluate whether this methodology suits their circumstances or whether alternative approaches might be more sustainable.

The Rich Guy Math provides data-driven financial education to improve financial literacy and decision-making. We do not provide individualized investment advice, tax guidance, or personalized financial planning services.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that explains the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and risk management.

With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based education, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable insights for beginner to intermediate investors. His teaching philosophy emphasizes understanding cause and effect in financial decisions rather than following generic advice.

Max’s work focuses on the intersection of behavioral finance, quantitative analysis, and practical wealth-building strategies. He believes financial literacy comes from understanding why money concepts work, not just what to do.

Through The Rich Guy Math, Max provides comprehensive guides on budgeting fundamentals, compound interest mechanics, investment strategies, and financial ratio analysis, all grounded in data, logic, and mathematical precision.

FAQs About Zero-Based Budgeting

Is zero-based budgeting realistic for everyday people?

Yes, but it requires time commitment and behavioral consistency. Zero-based budgeting works best for individuals who:

- Have predictable monthly income

- Can dedicate 2-4 hours monthly to budget creation

- Will track spending daily or weekly

- Have specific financial goals

The method becomes unrealistic when time is severely limited, income fluctuates dramatically, or the detailed tracking creates stress. In those cases, percentage-based methods like the 50/30/20 rule offer simpler alternatives.

How long does creating a zero-based budget take?

First month: 3-4 hours (setup)

Subsequent months: 1-2 hours

Daily tracking: 5-10 minutes

Weekly review: 15-20 minutes

Total monthly time commitment: 4-6 hours.

This investment typically saves $200-500 per month through spending awareness and waste elimination, creating an effective hourly rate of $35-85.

What if my income changes every month?

Variable income creates challenges, but solutions include:

- Conservative baseline: Budget to the lowest expected income, allocate surplus later.

- Percentage-based hybrid: Apply 50/30/20 to income, then use zero-based budgeting inside each category.

- Rolling average: Use 6-12 month income average. High months build buffer, low months draw from it.

Freelancers and commission earners often find percentage-based systems more sustainable.

What’s the difference between zero-based budgeting and the envelope system?

Zero-based budgeting assigns every dollar a job (Income – Expenses = $0).

The envelope system uses physical cash envelopes for spending control.

They can be combined:

- Use envelopes for variable categories (groceries, dining out)

- Track fixed expenses digitally (rent, utilities, savings)

Many zero-based budgeters use a hybrid approach.

Can I use credit cards with zero-based budgeting?

Yes. Credit cards are just a payment method, not extra money.

Best practices:

- Allocate purchases to categories immediately

- Track available balances, not credit limits

- Pay the full statement balance monthly

- Use cash envelopes for problem categories

Credit cards offer rewards and protection when used within budget limits.

How do I handle unexpected expenses in a zero-based budget?

Reallocate from other categories:

- Use a buffer/miscellaneous category

- Reduce discretionary spending temporarily

- Delay non-urgent purchases

Large expenses may require:

- Emergency fund

- Delaying the expense until next month

- Creating a sinking fund for future similar expenses

Example: $200 car repair

- $80 from dining out

- $50 from entertainment

- $70 from buffer

Is zero-based budgeting better than other budgeting methods?

It depends on goals, income stability, and personality.

Zero-based budgeting excels when:

- Precise tracking is needed

- Income is predictable

- Specific financial goals exist

Other methods work better when:

- Income varies monthly

- Time is limited

- Detailed tracking creates stress

The best budgeting method is the one used consistently.