Building wealth begins with a simple but powerful habit: saving money consistently.

Most people understand they should save, but few grasp the mathematical foundation that makes savings the cornerstone of financial stability. Saving money isn’t about deprivation—it’s about creating liquidity, building an emergency buffer, and establishing the foundation needed before investing for growth. Successful saving habits usually begin with budgeting and savings fundamentals that create a predictable cash flow and spending control.

The difference between financial stress and financial confidence often comes down to one factor: whether you’ve built adequate savings to handle life’s inevitable disruptions. This comprehensive guide explains the math behind money when it comes to saving, the account types that maximize your returns while maintaining safety, and the systematic approach that transforms sporadic saving into consistent wealth building.

Whether you’re establishing your first emergency fund, optimizing where you keep your cash, or determining how much to save before investing, this article provides the data-driven framework needed to make informed decisions about your savings strategy in 2026.

Key Takeaways

- Savings provide liquidity and safety, not growth; they serve a fundamentally different purpose than investing and should be kept in FDIC-insured accounts

- Aim to save 20% of gross income using the 50/30/20 rule, with a minimum emergency fund of 3-6 months of essential expenses

- High-yield savings accounts currently offer 4.0-5.0% APY in 2026, significantly outperforming traditional savings accounts at 0.01-0.50%

- Automate your savings using the “pay yourself first” principle, transfer money to savings immediately when income arrives, before discretionary spending occurs

- Build savings first, then invest, and establish your emergency fund before allocating capital to higher-risk, higher-return investment vehicles

What Does Saving Money Mean?

Saving money means setting aside liquid cash reserves in safe, accessible accounts for near-term needs and emergencies.

This definition is important because savings and investing serve distinct purposes in your financial life. Savings prioritize safety and liquidity over growth. The goal isn’t to maximize returns—it’s to ensure you have accessible funds when unexpected expenses arise or when planned short-term goals require cash.

The Core Purpose of Savings

Savings accounts serve three primary functions:

- Emergency buffer: Protecting against job loss, medical expenses, car repairs, and other unexpected costs

- Short-term goals: Funding planned expenses within 1-3 years (vacation, down payment, large purchases)

- Financial stability: Creating psychological security and preventing debt accumulation during disruptions

The math behind savings is straightforward. If you face a $5,000 emergency without savings, you’ll likely use credit cards at 18-25% APR or personal loans at 8-15% APR; the cost of not having savings compounds rapidly.

Example: A $5,000 emergency on a credit card at 20% APR takes 5 years to repay with minimum payments, costing $3,346 in interest, a 67% premium on the original expense.

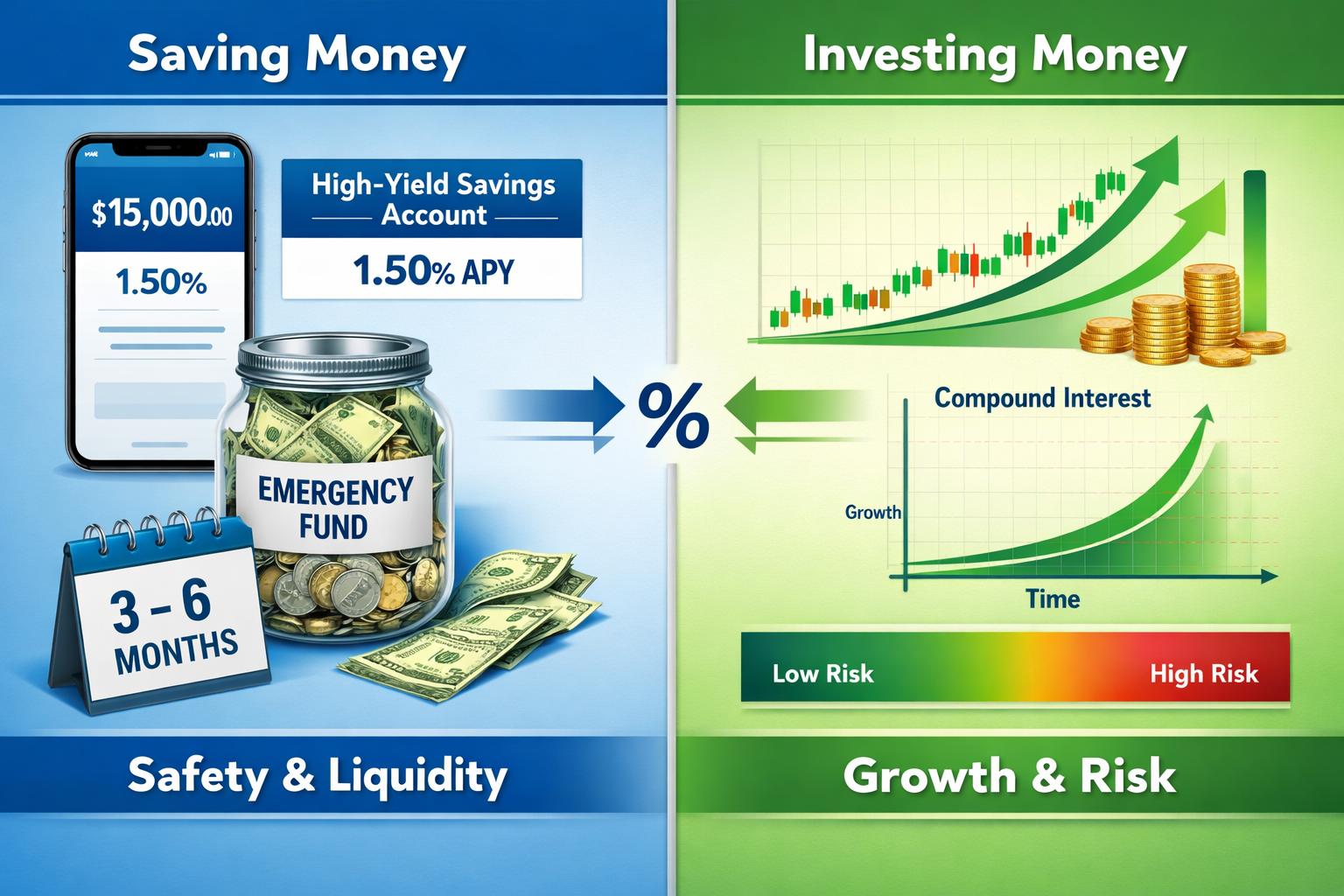

Savings vs Investing: The Critical Distinction

Savings and investing differ in three fundamental ways:

| Factor | Savings | Investing |

|---|---|---|

| Risk | Minimal (FDIC-insured) | Variable (market volatility) |

| Liquidity | Immediate access | May require selling assets |

| Return | 0.01-5.0% APY | Historical 7-10% average annually |

| Time Horizon | 0-3 years | 5+ years |

| Purpose | Stability & access | Growth & wealth building |

You save money in accounts. You invest money in assets.

This distinction determines where your money should go. Cash needed within 3 years belongs in savings vehicles. Money you won’t need for 5+ years belongs in investment vehicles that can weather market volatility and generate compound growth.

Insight: Savings create the foundation. Investing builds the structure. You cannot skip the foundation and expect the structure to remain stable during economic storms.

How Much Money Should You Save?

The amount you should save depends on two factors: your income level and your expense structure.

Data-driven financial planning uses both percentage-based rules and absolute dollar thresholds to determine adequate savings levels. The goal is to create sufficient liquidity without over-allocating to low-return cash positions.

Percentage-Based Savings Rules

The most widely recognized savings framework is the 50/30/20 rule, which allocates 20% of gross income to savings and debt repayment.

The 50/30/20 Breakdown:

- 50%: Essential expenses (housing, utilities, groceries, insurance, minimum debt payments)

- 30%: Discretionary spending (entertainment, dining out, hobbies, non-essential purchases)

- 20%: Savings and additional debt repayment

For someone earning $60,000 annually ($5,000 monthly), this means:

- $1,000 per month to savings

- $12,000 per year in accumulated savings (before considering interest)

This 20% savings rate creates meaningful wealth accumulation over time. At a 4.5% APY in a high-yield savings account, saving $1,000 monthly generates $12,287 after one year and $63,214 after five years.

Income-Based Variations:

Savings rates should adjust based on income level and financial goals:

- Lower income (<$40,000): Target 10-15% savings rate while building an emergency fund

- Middle income ($40,000-$100,000): Target 15-20% savings rate

- Higher income (>$100,000): Target 20-30% savings rate, transitioning excess to investments

The principle remains constant: save a consistent percentage of every dollar earned, adjusting the rate based on your capacity and goals.

Learn more about implementing this framework with the 50/30/20 budgeting rule.

Emergency Fund Guidelines

Beyond percentage-based savings, financial stability requires an emergency fund, a dedicated cash reserve covering 3-6 months of essential expenses.

Calculating Your Emergency Fund Target:

- List monthly essential expenses (housing, utilities, food, insurance, minimum debt payments)

- Multiply by 3-6 based on your situation

- Set this as your emergency fund target

Example Calculation:

- Monthly essentials: $3,000

- Conservative target (6 months): $18,000

- Aggressive target (3 months): $9,000

Factors That Determine Your Multiple:

- 6 months: Single-income household, variable income, self-employed, specialized career with longer job search timelines

- 3-4 months: Dual income household, stable employment, high-demand profession with quick rehiring potential

- 9-12 months: Extremely risk-averse, very high expenses, nearing retirement, or in an unstable industry

The Starter Emergency Fund Concept

For those beginning their savings journey, a starter emergency fund of $1,000-$2,000 provides immediate protection against minor emergencies while you build toward the full 3-6 month target.

This approach prevents analysis paralysis. Rather than feeling overwhelmed by an $18,000 goal, focus first on $1,000. This covers most minor emergencies (car repairs, medical co-pays, appliance replacement) and creates momentum.

Savings Priority Order:

- Build a $1,000 starter emergency fund

- Pay off high-interest debt (>10% APR)

- Complete a 3-6 month emergency fund

- Increase savings rate and begin investing

This sequence optimizes the mathematical return on your financial decisions. High-interest debt costs more than you can earn in savings, making debt elimination the priority after establishing basic emergency protection.

Takeaway: Save 20% of income as a baseline, with an absolute minimum emergency fund of 3-6 months’ expenses. Start with $1,000 if you’re beginning from zero.

For more insight into the emergency fund and to know how much to save, see our Emergency Fund Guides and How Much Money Should You Save monthly.

Where Should You Keep Your Savings?

The location of your savings determines both the safety of your principal and the interest you earn.

In 2026, savings account options range from traditional bank accounts earning 0.01% to high-yield savings accounts earning 4.0-5.0% APY. The difference compounds significantly over time, making account selection a critical financial decision.

High-Yield Savings Accounts (HYSA)

High-yield savings accounts offer the optimal combination of safety, liquidity, and returns for emergency funds and short-term savings goals.

Key Characteristics:

- APY Range (2026): 4.0-5.0% on average

- FDIC Insurance: $250,000 per depositor, per institution

- Liquidity: Immediate access via ACH transfer (1-3 business days)

- Minimum Balance: Often $0-$100

- Fees: Typically none

The Math Behind High-Yield Savings:

A $10,000 emergency fund in different account types over 5 years:

- Traditional savings (0.10% APY): $10,050

- High-yield savings (4.5% APY): $12,461

- Difference: $2,411 in additional earnings

The high-yield account generates $2,411 more without any additional risk or effort. This demonstrates the power of optimizing even conservative savings vehicles.

Top High-Yield Savings Account Features to Compare:

- Current APY (rates change monthly)

- Minimum deposit requirements

- Monthly maintenance fees

- Transfer limits and withdrawal restrictions

- Mobile app functionality

- Customer service quality

Most high-yield savings accounts are offered by online banks with lower overhead costs, allowing them to pass savings to customers through higher interest rates.

Explore the high-yield savings accounts for current rate comparisons and detailed reviews.

Traditional Savings Accounts

Traditional savings accounts at brick-and-mortar banks typically offer minimal interest rates but provide in-person banking access.

Key Characteristics:

- APY Range (2026): 0.01-0.50%

- FDIC Insurance: $250,000 per depositor, per institution

- Liquidity: Immediate access via branch, ATM, or transfer

- Minimum Balance: Often $25-$500

- Fees: $3-$10 monthly (often waived with minimum balance)

When Traditional Savings Make Sense:

- You strongly prefer in-person banking

- You’re already established with a bank and have a valuable relationship with banking

- You maintain high balances that waive fees

- You need frequent branch access for cash deposits

The Opportunity Cost:

For most savers, traditional savings accounts represent a significant opportunity cost. The difference between 0.10% and 4.5% APY on a $20,000 emergency fund equals $880 annually, enough to cover a month of groceries or a utility bill.

Insight: Unless you have specific needs requiring in-person banking, the mathematical advantage of high-yield savings accounts makes them the superior choice for emergency funds and short-term savings.

Money Market Accounts

Money market accounts blend features of checking and savings accounts, offering competitive interest rates with limited check-writing capabilities.

Key Characteristics:

- APY Range (2026): 3.5-4.5%

- FDIC Insurance: $250,000 per depositor, per institution

- Liquidity: High, with check-writing and debit card access

- Minimum Balance: Often $1,000-$10,000

- Fees: $10-$25 monthly (waived with minimum balance)

Money Market vs High-Yield Savings:

| Feature | Money Market | High-Yield Savings |

|---|---|---|

| Interest Rate | Competitive | Slightly higher |

| Check Writing | Yes (limited) | No |

| Debit Card | Often included | Rarely included |

| Minimum Balance | Higher | Lower or none |

| Best For | Larger balances, occasional access | Pure savings, emergency funds |

Money market accounts work well for savers who want slightly more flexibility than traditional savings accounts while maintaining competitive interest rates. However, the higher minimum balance requirements make them less suitable for those building their first emergency fund.

Takeaway: For most savers in 2026, high-yield savings accounts offer the best combination of safety, liquidity, and returns. Money market accounts serve as alternatives for larger balances requiring occasional check-writing access.

Saving vs Investing: What Comes First?

The sequence of saving before investing matters because it determines your financial resilience during market downturns and personal emergencies.

Many beginners make the mistake of investing before establishing adequate savings, creating a situation where they’re forced to sell investments at a loss during emergencies. The math behind proper sequencing prevents this costly error.

For a broader dive into Saving and investing, see our full guides on Saving vs Investing basics.

Risk and Timeline Differences

Savings and investing operate on different risk-return profiles:

Savings Risk Profile:

- Principal risk: None (FDIC-insured accounts)

- Inflation risk: Moderate (cash loses purchasing power over time)

- Liquidity risk: None (immediate access)

- Return expectation: 0.01-5.0% APY

Investing Risk Profile:

- Principal risk: High (market volatility can cause 20-50% declines)

- Inflation risk: Low (equity returns historically exceed inflation)

- Liquidity risk: Moderate (can sell, but may realize losses)

- Return expectation: 7-10% average annually (long-term historical)

The critical insight: investing requires time to recover from volatility. The S&P 500 has never produced a loss over any 20-year period, but has produced losses in 26% of all 1-year periods since 1928[1].

This statistical reality means money needed within 3-5 years should remain in savings vehicles, while money with a 5+ year horizon can tolerate market volatility and benefit from compound growth.

Priority Order for Financial Stability

The mathematically optimal sequence for allocating your money:

Phase 1: Foundation Building

- Save $1,000-$2,000 starter emergency fund

- Pay off credit card debt and high-interest loans (>10% APR)

- Complete a 3-6 month emergency fund in a high-yield savings account

Phase 2: Balanced Growth

- Contribute to employer 401(k) up to company match (free money)

- Increase emergency fund to 6-12 months if risk-averse or self-employed

- Begin investing in tax-advantaged accounts (IRA, HSA)

Phase 3: Wealth Acceleration

- Max out retirement accounts ($23,000 401(k), $7,000 IRA in 2026)

- Invest in taxable brokerage accounts

- Consider real estate, business ventures, or alternative investments

This sequence optimizes for both safety and growth. You protect against downside risk (emergency fund) before pursuing upside potential (investing).

Why This Order Matters Mathematically:

Without adequate savings, an emergency forces you to either:

- Take on high-interest debt: A credit card at 20% APR costs more than investment returns

- Sell investments at a loss: Forced selling during market downturns locks in losses and eliminates compound growth potential

Both outcomes destroy wealth. The emergency fund prevents these wealth-destroying scenarios.

Example: During the 2020 COVID-19 market crash, the S&P 500 declined 34% from February to March. An investor without savings who lost their job would have been forced to sell investments at a 34% loss. An investor with 6 months of savings could wait for the recovery, which reached new highs by August 2020.

The investor with savings preserved their capital and captured the subsequent 100%+ rally. The investor without savings locked in a 34% loss.

Insight: Savings create the financial stability that allows you to be a successful long-term investor. The sequence matters as much as the amounts.

Explore more about investing fundamentals after establishing your savings foundation.

How to Build a Consistent Saving System

Consistency matters more than intensity when building savings.

The behavioral challenge of saving isn’t understanding the math; it’s executing the habit repeatedly over months and years. A systematic approach removes willpower from the equation, making savings automatic rather than optional.

Automating Savings

Automation transforms saving from a monthly decision into a background process that happens without conscious effort.

The “Pay Yourself First” Principle:

Traditional budgeting follows this sequence:

- Receive income

- Pay bills and expenses

- Save whatever remains (often nothing)

The pay-yourself-first approach reverses this:

- Receive income

- Automatically transfer to savings

- Pay bills and expenses with remaining funds

This simple reversal creates a forcing function. By removing savings from your checking account immediately, you adapt spending to the remaining balance rather than hoping money remains at month’s end.

How to Implement Automatic Savings:

- Calculate your savings target: 20% of gross income or a specific monthly amount

- Set up automatic transfers: Schedule transfers from checking to savings on payday

- Separate accounts: Use different banks for checking and savings to create friction for accessing savings

- Increase gradually: Start with 10% if 20% feels overwhelming, then increase by 1% every 3 months

Example Automation Setup:

- Income: $5,000 monthly (paid on 1st and 15th)

- Savings target: 20% = $1,000 monthly

- Automatic transfer: $500 on the 2nd and 16th (day after payday)

This system ensures savings happen before discretionary spending depletes available funds.

The Mathematical Impact of Automation:

Manual saving (saving “whatever’s left”) typically results in 3-8% actual savings rates due to lifestyle inflation and discretionary spending. Automated saving consistently achieves target rates of 15-20%+.

Over 10 years, this difference compounds significantly:

- Manual saving (5% rate): $38,635 saved from a $60,000 annual income

- Automated saving (20% rate): $154,540 saved from a $60,000 annual income

- Difference: $115,905 additional savings

Automation doesn’t require more income or more discipline; it requires a one-time setup that removes future decisions.

Budget Integration

Savings work best when integrated into a comprehensive budget that tracks income, expenses, and financial goals.

Zero-Based Budgeting for Savings:

Zero-based budgeting assigns every dollar a purpose before the month begins:

- Income: $5,000

- Savings: $1,000 (20%)

- Housing: $1,500 (30%)

- Transportation: $500 (10%)

- Food: $600 (12%)

- Insurance: $300 (6%)

- Debt payments: $400 (8%)

- Discretionary: $700 (14%)

- Total allocated: $5,000 (100%)

This approach makes savings a fixed expense rather than a variable that depends on spending restraint. You budget for savings the same way you budget for rent, as a non-negotiable commitment.

Tracking Tools:

- Spreadsheet templates (free, customizable)

- Budgeting apps (Mint, YNAB, EveryDollar)

- Bank account categorization features

- Manual envelope system (cash-based budgeting)

The tool matters less than the habit. Consistent monthly budget reviews, even 15 minutes, create awareness that prevents overspending and ensures savings targets are met.

Pay Yourself First Implementation

The pay-yourself-first principle extends beyond automation to a mindset shift about savings priority.

Practical Implementation Steps:

- Calculate net income: Determine actual take-home pay after taxes

- Set savings percentage: Start with 10-20% based on current financial situation

- Open a separate savings account: Preferably at a different bank than your checking account

- Schedule automatic transfer: Set for the day after payday

- Adjust spending accordingly: Adapt lifestyle to remaining funds

Psychological Benefits:

Paying yourself first creates positive reinforcement. You see your savings account grow consistently, which motivates continued discipline. This contrasts with the frustration of trying to save “whatever’s left” and frequently having nothing to save.

Overcoming Common Objections:

- “I don’t earn enough to save 20%”: Start with 5-10% and increase gradually as income grows

- “I have too many expenses”: Review expenses for reduction opportunities; most households have 10-20% discretionary spending that can be optimized

- “What if I need the money?”: That’s what the emergency fund is for, build it first, then increase savings rate

Takeaway: Automation and systematic budgeting will remove willpower from the savings equation. Set up the system once, then let it run in the background while you focus on increasing income and optimizing expenses.

Short-Term and Long-Term Savings Goals

Effective saving requires distinguishing between short-term and long-term goals, as each requires different strategies and account types.

The timeline of your goal determines the appropriate savings vehicle and the urgency of accumulation.

Short-Term Savings Goals (0-3 Years)

Short-term savings goals require liquidity and capital preservation. These funds will be spent within 3 years, meaning market volatility poses unacceptable risk.

Common Short-Term Savings Goals:

- Emergency fund: 3-6 months’ expenses

- Vacation: $2,000-$10,000 depending on destination and duration

- Vehicle down payment: 20% of purchase price (see our 20/4/10 rule guide)

- Home down payment: 10-20% of purchase price

- Wedding: $5,000-$30,000 average cost

- Medical procedures: Elective procedures, fertility treatments, dental work

- Large purchases: Appliances, furniture, electronics

Optimal Account Type: High-yield savings account or money market account

Savings Strategy:

- Calculate total cost

- Determine timeline (months until needed)

- Divide the cost by the months to get the monthly savings target

- Set up an automatic monthly transfer

Example: Vacation Savings

- Goal: $6,000 vacation in 18 months

- Monthly savings needed: $6,000 ÷ 18 = $333/month

- Account: High-yield savings at 4.5% APY

- Interest earned: ~$225 over 18 months

- Total available: $6,225

The interest earned provides a small bonus, but the primary goal is capital preservation and accessibility.

Long-Term Savings Goals (3+ Years)

Long-term goals blur the line between savings and investing. Money not needed for 5+ years should typically transition to investment vehicles that offer higher returns despite increased volatility.

Common Long-Term Goals:

- Retirement: 20-40+ year timeline

- Children’s education: 10-18 year timeline

- Major home renovation: 5-10 years

- Starting a business: 3-7 years of capital accumulation

- Financial independence: 10-30+ years

Optimal Account Type:

- 3-5 years: Mix of high-yield savings (60-80%) and conservative investments (20-40%)

- 5+ years: Primarily investment accounts (stocks, bonds, index funds)

The Transition Point:

The mathematical decision point for moving from savings to investing occurs around the 3-5 year mark:

- Less than 3 years: Keep 100% in savings (capital preservation priority)

- 3-5 years: Hybrid approach (balance safety and growth)

- More than 5 years: Invest majority (growth priority, time to recover from volatility)

This timeline-based approach optimizes the risk-return tradeoff based on when you need access to the funds.

Sinking Funds Strategy

A sinking fund is a dedicated savings account for a specific future expense. Rather than one general savings account, you create multiple targeted accounts for different goals.

Example Sinking Fund Structure:

| Goal | Monthly Deposit | Timeline | Target Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency Fund | $500 | Ongoing | $15,000 |

| Vacation | $200 | 12 months | $2,400 |

| Car Replacement | $300 | 36 months | $10,800 |

| Home Maintenance | $150 | Ongoing | $5,000 buffer |

| Total | $1,150 | — | — |

This approach creates clarity and prevents “borrowing” from one goal to fund another. You know exactly how much you have available for each specific purpose.

Implementation:

- Use sub-accounts within your high-yield savings account (many banks offer this feature)

- Use separate accounts at different institutions

- Track manually in a spreadsheet with a single savings account

The psychological benefit: seeing progress toward specific goals creates stronger motivation than watching a general savings account grow.

Takeaway: Match your savings vehicle to your timeline. Short-term goals (0-3 years) belong in high-yield savings accounts. Long-term goals (5+ years) should transition to investment vehicles that generate compound growth.

Common Saving Mistakes to Avoid

Even disciplined savers make strategic errors that reduce the effectiveness of their savings efforts.

Understanding these common mistakes allows you to optimize your approach and avoid wealth-destroying behaviors.

Mistake 1: Keeping Too Much in Cash

While savings provide essential liquidity, keeping too much money in low-return savings accounts creates opportunity costs.

The Inflation Problem:

Inflation in 2026 averages 2-3% annually[2]. A high-yield savings account earning 4.5% provides a real return of approximately 1.5-2.5% after inflation. This barely preserves purchasing power.

Money that won’t be needed for 5+ years should be invested in assets with higher growth potential. The S&P 500 has returned an average of 10.2% annually since 1957, significantly outpacing both inflation and savings account returns[3].

The Opportunity Cost:

$50,000 kept in savings vs. invested over 20 years:

- High-yield savings (4.5% APY): $122,208

- S&P 500 index fund (10% average): $336,375

- Opportunity cost: $214,167 in lost growth

This demonstrates why you should maintain only the necessary emergency fund and short-term savings in cash accounts, investing the remainder for long-term goals.

Optimal Cash Allocation:

- Emergency fund: 3-6 months’ expenses

- Short-term goals: Money needed within 3 years

- Everything else: Invest for growth

Mistake 2: Not Earning Competitive Interest

Keeping savings in traditional bank accounts earning 0.01-0.10% APY represents a significant wealth leak.

The Math:

$20,000 emergency fund over 5 years:

- Traditional savings (0.10% APY): $20,100

- High-yield savings (4.5% APY): $24,922

- Lost earnings: $4,822

The difference requires zero additional risk—both accounts carry FDIC insurance. The only difference is choosing a high-yield account over a traditional account.

Action Step: If your savings account earns less than 4.0% APY in 2026, transfer to a high-yield savings account. This takes 15 minutes and generates thousands in additional earnings over time.

Compare current rates at the best high-yield savings accounts.

Mistake 3: No Emergency Fund Buffer

Operating without an emergency fund forces you into high-interest debt when unexpected expenses arise.

The Debt Spiral:

Without savings, a $3,000 car repair goes on a credit card at 22% APR. Making minimum payments ($90/month), you’ll pay $1,247 in interest over 47 months—a 42% premium on the original expense.

This single emergency without savings costs more than a year of high-yield savings account earnings on a $20,000 emergency fund.

Statistical Reality:

- 40% of Americans cannot cover a $400 emergency expense without borrowing[4]

- The average household experiences 2-3 unexpected expenses of $500+ annually

- Medical, vehicle, and home maintenance emergencies are statistically inevitable

The emergency fund isn’t pessimism—it’s mathematical preparation for statistical certainty.

Mistake 4: Lifestyle Inflation

Lifestyle inflation occurs when expenses increase proportionally with income, preventing savings rate growth.

The Pattern:

- Entry-level job: Earn $45,000, save $4,500 (10%)

- Promotion: Earn $65,000, save $6,500 (10%)

- Senior role: Earn $95,000, save $9,500 (10%)

While absolute savings increase, the percentage remains constant. This represents a missed opportunity.

Optimized Approach:

- Entry-level: Earn $45,000, save $4,500 (10%)

- Promotion: Earn $65,000, save $13,000 (20%)—save 50% of raise

- Senior role: Earn $95,000, save $28,500 (30%)—save 50% of raise

By saving 50% of each raise and living on the other 50%, you increase your savings rate dramatically while still improving your lifestyle.

The Compound Effect:

Saving 10% vs. 30% of $95,000 income over 20 years at 8% return:

- 10% savings rate: $433,691

- 30% savings rate: $1,301,074

- Difference: $867,383

Lifestyle inflation is the silent killer of wealth accumulation. Combat it by automatically increasing your savings rate with each raise.

Takeaway: Avoid over-allocating to cash, ensure you’re earning competitive interest rates, maintain an adequate emergency fund, and resist lifestyle inflation as income grows.

How Safe Are Savings Accounts?

Safety represents the primary advantage of savings accounts over investment vehicles.

Understanding the protections that safeguard your savings creates confidence in maintaining appropriate cash reserves.

FDIC Insurance Fundamentals

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) provides insurance on bank deposits up to $250,000 per depositor, per insured bank, per ownership category[5].

What FDIC Insurance Covers:

- Savings accounts

- Checking accounts

- Money market deposit accounts

- Certificates of deposit (CDs)

What FDIC Insurance Does NOT Cover:

- Stocks

- Bonds

- Mutual funds

- Annuities

- Cryptocurrency

- Safe deposit box contents

The $250,000 Limit:

FDIC insurance covers $250,000 per depositor, per institution, per ownership category. This means you can have more than $250,000 insured by using different ownership structures:

Example Coverage:

- Individual account at Bank A: $250,000 covered

- Joint account at Bank A: $500,000 covered ($250,000 per owner)

- Individual account at Bank B: $250,000 covered

- Total FDIC coverage: $1,000,000

For savings above $250,000, distribute funds across multiple FDIC-insured institutions to maintain full coverage.

Bank Failure Protection

FDIC insurance protects depositors when banks fail. Since the FDIC’s creation in 1933, no depositor has lost a single cent of FDIC-insured deposits[6].

Historical Context:

During the 2008 financial crisis, 465 banks failed between 2008 and 2012. In every case, FDIC insurance protected depositors up to the coverage limits. Depositors typically received access to funds within 1-2 business days through either:

- Purchase and assumption: Another bank acquires the failed bank, and accounts transfer seamlessly

- Direct payout: FDIC issues checks to depositors for insured amounts

Verification:

Confirm your bank has FDIC insurance:

- Look for the FDIC logo on the bank’s website and physical locations

- Search the FDIC BankFind tool: https://banks.data.fdic.gov/bankfind-suite/bankfind

- Check your account statements for FDIC insurance disclosure

Never keep significant savings in non-FDIC-insured institutions or accounts.

Account Ownership Categories

FDIC insurance limits apply per ownership category, allowing strategic structuring for balances above $250,000:

Ownership Categories:

- Single accounts: $250,000 per owner

- Joint accounts: $250,000 per co-owner

- Retirement accounts (IRA, 401k rollovers): $250,000 per owner

- Revocable trust accounts: $250,000 per beneficiary

- Irrevocable trust accounts: $250,000 per beneficiary

- Business accounts: $250,000 per business entity

Example: Maximizing Coverage:

A married couple can structure accounts for maximum FDIC coverage:

- Spouse A individual account: $250,000

- Spouse B individual account: $250,000

- Joint account: $500,000 ($250,000 per owner)

- Total coverage at one bank: $1,000,000

For balances exceeding these limits, use multiple FDIC-insured institutions.

Takeaway: FDIC insurance makes savings accounts one of the safest places to store money. Verify your bank has FDIC coverage and structure accounts appropriately if you have balances exceeding $250,000.

What To Do After Building Your Savings

Once you’ve established adequate savings, the next phase focuses on wealth building through investing and long-term financial planning.

Savings create the foundation. Investing builds the structure that generates compound growth and financial independence.

Transition from Saving to Investing

The transition from saver to investor occurs when you’ve achieved these milestones:

Prerequisites for Investing:

- ✅ 3-6 month emergency fund fully funded

- ✅ High-interest debt eliminated (>8% APR)

- ✅ Consistent monthly savings habit established

- ✅ Short-term savings goals (0-3 years) funded or on track

Once these foundations are in place, additional savings should transition to investment vehicles that generate higher returns over longer time horizons.

Investment Priority Order:

- Employer 401(k) match: Contribute enough to capture full employer match (typically 3-6% of salary)—this represents a 50-100% immediate return

- Health Savings Account (HSA): Max contribution if you have a high-deductible health plan ($4,150 individual, $8,300 family in 2026)

- IRA or Roth IRA: Max contribution ($7,000 in 2026, $8,000 if age 50+)

- Max 401(k): Increase contributions to annual limit ($23,000 in 2026, $30,500 if age 50+)

- Taxable brokerage account: Invest additional savings in diversified index funds

This sequence optimizes for tax advantages and employer contributions before moving to taxable accounts.

Retirement Planning

Retirement represents the ultimate long-term savings goal, requiring decades of consistent contributions and compound growth.

The 4% Rule:

The 4% rule provides a framework for retirement savings targets. It states you can withdraw 4% of your retirement portfolio annually with a high probability of not running out of money over a 30-year retirement.

Retirement Savings Calculation:

- Annual retirement expenses: $60,000

- Required portfolio size: $60,000 ÷ 0.04 = $1,500,000

This means you need 25 times your annual expenses saved to retire sustainably.

Time Value of Retirement Savings:

Starting early creates exponential advantages due to compound growth:

$500 monthly investment at 8% return:

- Start at age 25, retire at 65: $1,745,503

- Start at age 35, retire at 65: $745,179

- Start at age 45, retire at 65: $297,571

The 10-year head start from age 25 to 35 generates over $1 million in additional retirement wealth, despite only $60,000 more in contributions.

Insight: Time is the most powerful variable in wealth building. Once you’ve established your emergency fund, prioritize retirement contributions to maximize compound growth.

Explore more about retirement planning strategies and calculations.

Debt Payoff Strategy

After building your emergency fund, focus on eliminating high-interest debt before aggressive investing.

The Mathematical Threshold:

- Interest rate >8%: Pay off before investing beyond the employer match

- Interest rate 4-8%: Balance debt payoff with investing

- Interest rate <4%: Make minimum payments, prioritize investing

Reasoning: Paying off 18% APR credit card debt guarantees an 18% return, better than average stock market returns. Paying off a 3% mortgage early while forgoing 10% investment returns costs you 7% annually in opportunity cost.

Debt Payoff Methods:

- Avalanche method: Pay the highest interest rate debt first (mathematically optimal)

- Snowball method: Pay the smallest balance first (psychologically motivating)

Both work. The avalanche method saves more money in interest. The snowball method creates momentum through quick wins.

Choose the method you’ll actually execute consistently.

Takeaway: After establishing your savings foundation, transition to wealth building through investing, retirement planning, and strategic debt elimination. The savings foundation enables these wealth-building activities by providing financial stability.

Savings Goal Calculator

Calculate your emergency fund target and monthly savings needed

💡 Pro Tip: Automate your savings by setting up automatic transfers the day after payday. This “pay yourself first” strategy ensures consistent progress toward your emergency fund goal without relying on willpower.

Conclusion

Saving money creates the foundation for every other financial goal, from emergency preparedness to long-term wealth building.

The math behind effective saving is straightforward: maintain 3-6 months of expenses in a high-yield savings account earning 4.0-5.0% APY, save 20% of gross income consistently, and automate the process to remove willpower from the equation.

Savings and investing serve different purposes. Savings provide liquidity and safety for short-term needs and emergencies. Investing generates compound growth for long-term goals like retirement and financial independence. You need both, in the proper sequence.

The systematic approach outlined in this guide, establishing emergency funds, choosing appropriate account types, automating contributions, and avoiding common mistakes, transforms saving from an occasional activity into a consistent wealth-building habit.

Your Next Steps:

- Calculate your emergency fund target (3-6 months’ expenses)

- Open a high-yield savings account if you don’t have one

- Set up automatic transfers for 20% of income (or start with 10% and increase gradually)

- Once the emergency fund is complete, transition additional savings to investing

Building strong saving habits creates the financial foundation needed for long-term stability and wealth growth. Start with the first step today—your future self will thank you.

Disclaimer

This article provides educational information about saving strategies, account types, and financial planning principles. It does not constitute financial advice, investment recommendations, or professional guidance tailored to your specific situation.

Financial decisions should be based on your individual circumstances, risk tolerance, time horizon, and goals. Interest rates, account features, and tax rules change over time and vary by institution and jurisdiction.

Before making significant financial decisions, consult with qualified financial advisors, tax professionals, or certified financial planners who can provide personalized guidance based on your complete financial picture.

The Rich Guy Math provides data-driven financial education to help readers understand the math behind money. We do not receive compensation for specific product recommendations and maintain editorial independence.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that explains the math behind money with precision and authority. With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based investing, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable guidance for beginner to intermediate investors.

Max’s approach combines analytical rigor with educational clarity, helping readers understand not just what to do with their money, but why specific strategies work based on mathematical principles and historical data.

Learn more about The Rich Guy Math’s mission and methodology at our About Us page, or explore our comprehensive library of financial literacy resources.

References

[1] S&P 500 Historical Returns Analysis, 1928-2024. S&P Dow Jones Indices. https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/

[2] Consumer Price Index Summary, 2024-2026. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/

[3] Long-Term Stock Market Returns and Historical Data. Morningstar Investment Research. https://www.morningstar.com/

[4] Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households. Federal Reserve Board. https://www.federalreserve.gov/

[5] FDIC Insurance Coverage Basics. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. https://www.fdic.gov/

[6] FDIC History and Bank Failure Statistics. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/

Frequently Asked Questions

What is saving money?

Saving money means setting aside liquid cash reserves in safe, easily accessible accounts—such as high-yield savings accounts—for near-term needs and emergencies.

Savings prioritize safety and liquidity over growth and serve a different purpose than investing.

How much money should I save?

A common guideline is to save at least 20% of your gross income. At a minimum, you should build an emergency fund covering 3 to 6 months of essential expenses.

If you’re starting from zero, begin with a $1,000 starter emergency fund, then gradually work toward the full 3–6 month target.

Where should I keep my savings?

Keep savings in FDIC-insured high-yield savings accounts earning approximately 4.0%–5.0% APY in 2026. These accounts balance safety, liquidity, and competitive returns.

Avoid traditional savings accounts earning 0.01%–0.50% APY due to the long-term opportunity cost.

What’s the difference between saving and investing?

Saving keeps money in low-risk, liquid accounts for short-term needs (0–3 years). Investing allocates money to higher-risk assets, such as stocks, for long-term growth (5+ years).

Build your emergency fund first, then invest surplus money to grow wealth over time.

How do I start saving money consistently?

Use the “pay yourself first” method by automating savings. Set up automatic transfers from checking to savings the day after payday for 10%–20% of your income.

Automation removes reliance on willpower and ensures saving happens before discretionary spending.

Are savings accounts safe?

Yes. Savings accounts at FDIC-insured banks are extremely safe. FDIC insurance protects deposits up to $250,000 per depositor, per