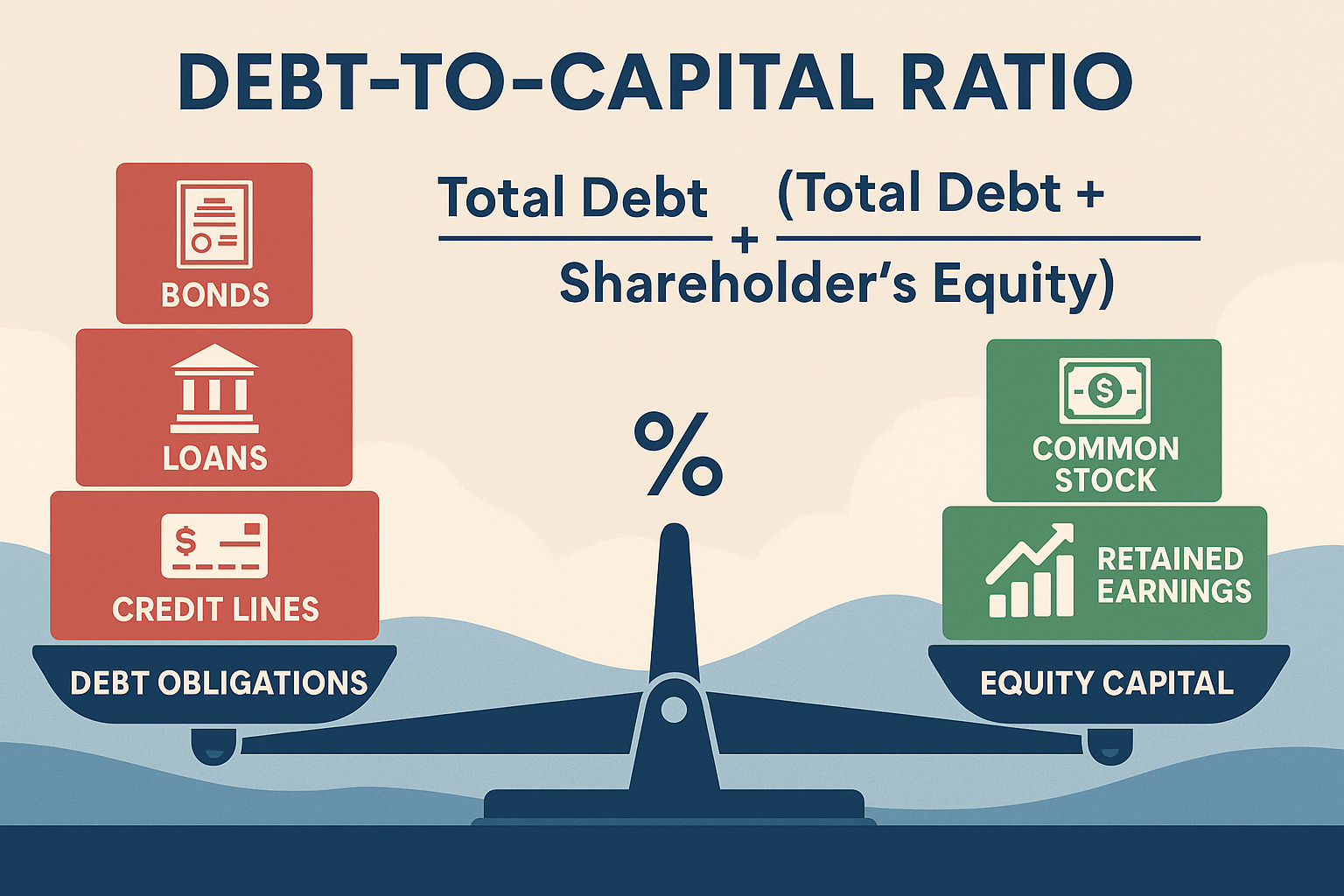

When a company needs money to grow, it faces a fundamental choice: borrow it or raise it from investors. The Debt-to-Capital Ratio reveals exactly how that choice plays out, showing the precise balance between borrowed funds and owner-invested capital that powers every business decision.

This single metric tells investors, lenders, and business owners whether a company leans on debt or equity to fund operations. Understanding this ratio means understanding the math behind financial risk, capital structure decisions, and long-term business sustainability.

The debt-to-capital ratio measures financial leverage by comparing interest-bearing debt to total available capital. It answers a critical question: What percentage of a company’s funding comes from borrowed money versus owner equity?

This guide breaks down the definition, formula, calculation process, and practical interpretation of the debt-to-capital ratio. By the end, the numbers on any balance sheet will reveal clear insights about financial health and risk management.

Key Takeaways

- The debt-to-capital ratio measures leverage by dividing total interest-bearing debt by total capital (debt plus equity), expressed as a percentage or decimal

- The formula is straightforward: Total Debt ÷ (Total Debt + Shareholder’s Equity) = Debt-to-Capital Ratio

- A ratio of 0.50 means 50% debt funding—half the company’s capital comes from borrowed money, half from equity investors

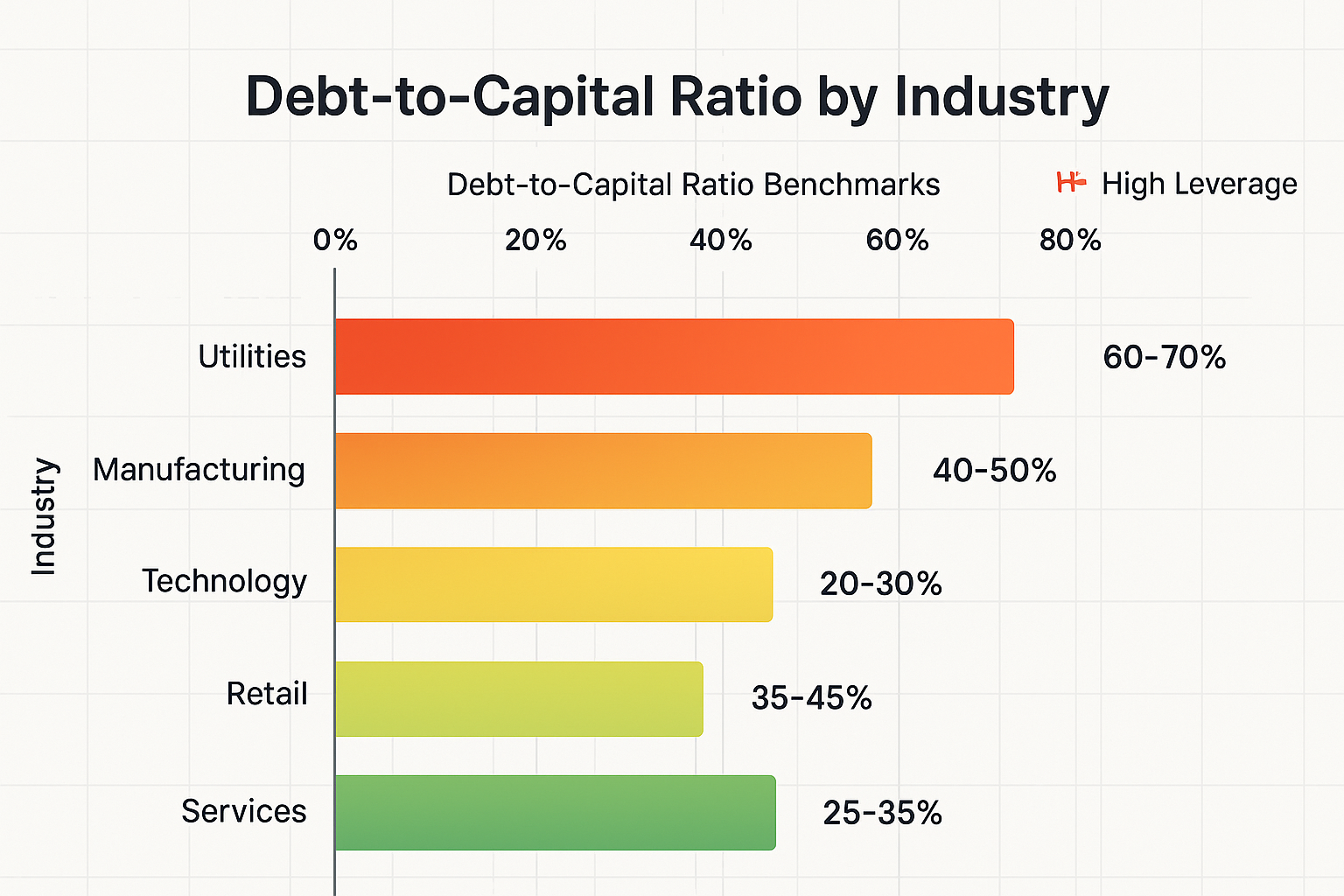

- Industry context matters critically—utilities average 60-70% while technology companies often maintain 20-30% ratios

- Higher ratios indicate greater financial risk because debt obligations must be paid regardless of business performance

What Is the Debt-to-Capital Ratio?

The debt-to-capital ratio is a financial metric that quantifies how much of a company’s capital structure consists of borrowed funds versus owner-invested equity.

It specifically measures interest-bearing debt, not all liabilities, against the total capital available to the business. This distinction matters because not all balance sheet obligations carry the same financial weight or risk profile.

Why This Ratio Matters

Capital structure determines financial flexibility. Companies with high debt ratios face mandatory interest payments and principal repayment schedules, regardless of revenue performance.

Those relying more heavily on equity financing avoid fixed payment obligations but dilute ownership among more shareholders. The debt-to-capital ratio quantifies this fundamental trade-off.

Investors use this metric to assess financial risk before committing capital. Lenders examine it to determine creditworthiness and appropriate interest rates. Management teams monitor it to maintain an optimal capital structure that balances growth opportunities with financial stability.

The Math Behind Capital Structure

Every dollar funding business operations comes from exactly two sources: debt or equity. There is no third option.

Debt represents borrowed capital that must be repaid with interest. Equity represents ownership stakes that share in profits and losses without mandatory repayment schedules.

The debt-to-capital ratio expresses this binary choice as a percentage. A company with $600 million in debt and $400 million in equity has a debt-to-capital ratio of 0.60 or 60%, meaning 60 cents of every capital dollar comes from borrowing.

This mathematical relationship drives every subsequent financial decision, from dividend policies to expansion strategies to risk management approaches.

The Debt-to-Capital Ratio Formula Explained

The standard formula for calculating the debt-to-capital ratio follows a simple mathematical structure:

Debt-to-Capital Ratio = Total Debt ÷ (Total Debt + Shareholder’s Equity)

This formula can also be expressed as:

Debt-to-Capital Ratio = Total Debt ÷ Total Capitalization

Both versions produce identical results because total capitalization equals the sum of all debt and equity funding sources.

Breaking Down Each Component

Total Debt includes all interest-bearing obligations on the balance sheet:

- Long-term debt (bonds, term loans, mortgages)

- Short-term debt (lines of credit, current portions of long-term debt)

- Capital leases and equipment financing

- Any other borrowed funds carrying interest charges

Shareholders’ Equity encompasses all ownership-based capital:

- Common stock and preferred stock at par value

- Additional paid-in capital above par value

- Retained earnings accumulated over time

- Treasury stock (subtracted)

- Minority interest in subsidiaries

Total Capitalization represents the complete funding base, every dollar available for working capital and capital expenditures.

What Gets Excluded

The formula specifically excludes non-interest-bearing liabilities like accounts payable, accrued expenses, and deferred revenue.

These items appear on the balance sheet but don’t represent capital structure decisions. They arise from normal business operations rather than deliberate financing choices.

This focus on interest-bearing debt provides a clearer picture of financial leverage and the cost of capital. Operating liabilities don’t carry interest charges or create the same refinancing risks as formal debt obligations.

How to Calculate Debt-to-Capital Ratio: Step-by-Step Process

Calculating the debt-to-capital ratio requires extracting specific numbers from a company’s balance sheet. Follow this systematic approach:

Step 1: Locate the Balance Sheet

Find the most recent balance sheet in the company’s quarterly (10-Q) or annual (10-K) financial reports. Public companies file these documents with the SEC and make them available on investor relations websites.

The balance sheet presents assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific point in time, typically the last day of a fiscal quarter or year.

Step 2: Identify Total Debt

Look for these line items under liabilities:

- Current portion of long-term debt (due within 12 months)

- Short-term borrowings or notes payable

- Long-term debt (due beyond 12 months)

- Capital lease obligations

Add these amounts together to calculate the total interest-bearing debt. Some balance sheets provide a subtotal labeled “total debt” for convenience.

Step 3: Find Shareholders’ Equity

Locate the equity section at the bottom of the balance sheet. This section typically includes:

- Common stock

- Preferred stock

- Additional paid-in capital

- Retained earnings

- Accumulated other comprehensive income

- Treasury stock (negative value)

The balance sheet should provide a line labeled “total shareholders’ equity” or “total stockholders’ equity” that sums these components.

Step 4: Apply the Formula

Insert the numbers into the formula:

Debt-to-Capital Ratio = Total Debt ÷ (Total Debt + Total Equity)

The result can be expressed as a decimal (0.45) or percentage (45%).

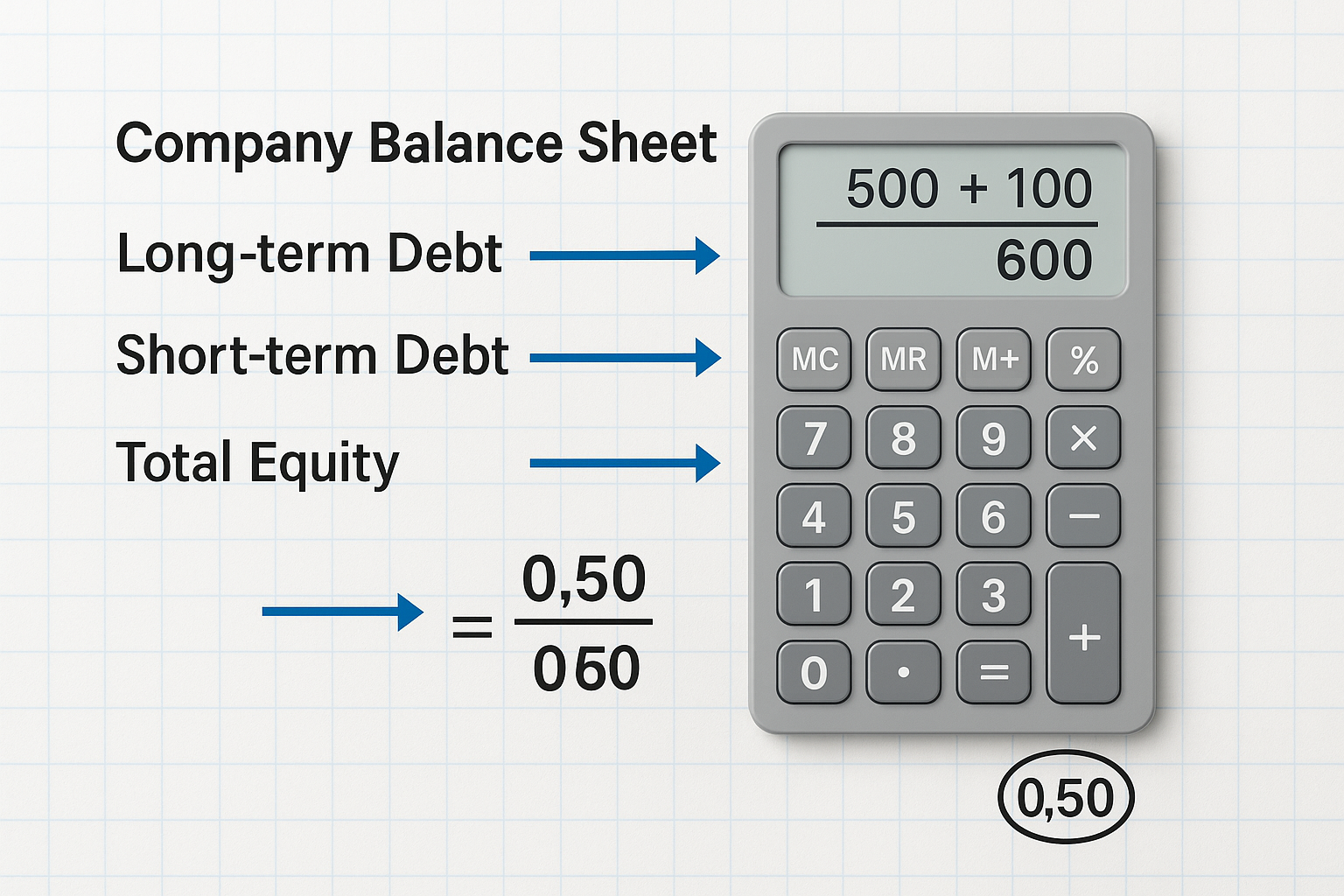

Practical Calculation Example

Consider a company with the following balance sheet data:

- Long-term debt: $500 million

- Short-term debt: $100 million

- Total shareholders’ equity: $600 million

Total Debt = $500M + $100M = $600M

Total Capitalization = $600M + $600M = $1,200M

Debt-to-Capital Ratio = $600M ÷ $1,200M = 0.50 or 50%

This company funds exactly half its operations through borrowed capital and half through equity investment. For every dollar of capital employed, 50 cents comes from debt and 50 cents from shareholders.

Understanding similar metrics like the debt-to-equity ratio and debt-to-asset ratio provides additional context for evaluating financial leverage.

Interpreting Debt-to-Capital Ratio Results

The calculated ratio reveals the company’s capital structure positioning, but interpretation requires context and comparison.

What Different Ratios Mean

0.00 to 0.20 (0% to 20%)

- Very low leverage

- Minimal debt financing

- Conservative capital structure

- Lower financial risk, but potentially underutilizing debt’s tax advantages

0.20 to 0.40 (20% to 40%)

- Moderate leverage

- Balanced capital structure

- Common among growth companies and technology firms

- Manageable debt service with equity cushion

0.40 to 0.60 (40% to 60%)

- Substantial leverage

- Significant debt component

- Typical for mature, stable industries

- Requires consistent cash flow for debt service

0.60 to 0.80 (60% to 80%)

- High leverage

- Debt-heavy capital structure

- Common in capital-intensive industries like utilities

- Elevated financial risk during downturns

Above 0.80 (Above 80%)

- Very high leverage

- Potential financial distress indicators

- Limited equity cushion

- Vulnerable to cash flow disruptions

Industry Benchmarks Matter

No universal “ideal” ratio exists because different industries operate under different economic models and capital requirements.

Capital-Intensive Industries (utilities, telecommunications, real estate):

- Average ratios: 60-70%

- Require massive infrastructure investments

- Generate stable, predictable cash flows

- Can safely carry higher debt loads

Asset-Light Industries (technology, software, consulting):

- Average ratios: 20-30%

- Minimal fixed asset requirements

- Variable revenue streams

- Prefer equity financing flexibility

Cyclical Industries (manufacturing, retail, automotive):

- Average ratios: 35-50%

- Revenue fluctuates with economic cycles

- Balance debt benefits with recession resilience

- Moderate leverage provides optimal flexibility

Compare companies only within the same industry sector. A 65% ratio signals financial strength for a utility company but potential distress for a software firm.

The Relationship to Financial Risk

Higher debt-to-capital ratios amplify both returns and risks through financial leverage. This mathematical relationship works in both directions.

During Growth Periods:

- Debt magnifies returns on equity

- Fixed interest costs remain constant while revenues grow

- Shareholders capture outsized gains

During Downturns:

- Debt obligations continue regardless of revenue

- Cash flow pressure increases

- Default risk rises

- Equity value can evaporate quickly

The degree of operating leverage combined with financial leverage determines total business risk exposure.

Companies with high debt ratios must maintain strong cash flow generation to service obligations. The debt service coverage ratio measures this capacity directly.

Debt-to-Capital Ratio vs Other Leverage Metrics

Several related metrics measure financial leverage from different angles. Understanding the distinctions prevents analytical confusion.

Debt-to-Capital vs Debt-to-Equity Ratio

The debt-to-equity ratio divides total debt by total equity:

Debt-to-Equity = Total Debt ÷ Total Equity

This metric isolates the relationship between the two capital sources without combining them into a denominator.

Key Difference:

- Debt-to-equity ratio can exceed 1.0 (or 100%)

- Debt-to-capital ratio cannot exceed 1.0 by definition

- Debt-to-equity emphasizes the relative proportion

- Debt-to-capital shows the percentage composition

Conversion Formula:

If debt-to-equity = 1.5, then debt-to-capital = 1.5 ÷ (1 + 1.5) = 0.60 or 60%

Both metrics convey the same underlying information but express it differently. Financial analysts often use them interchangeably with appropriate conversion.

Debt-to-Capital vs Debt Ratio

The debt ratio divides total debt by total assets:

Debt Ratio = Total Debt ÷ Total Assets

This metric compares debt to the entire asset base rather than just capital sources.

Key Difference:

- Debt ratio includes all assets (funded by debt, equity, and liabilities)

- Debt-to-capital ratio focuses only on capital structure

- The debt ratio provides a broader balance sheet perspective

- Debt-to-capital ratio isolates financing decisions

The debt-to-capital ratio offers clearer insight into management’s deliberate capital structure choices.

Debt-to-Capital vs. Capitalization Ratio

The capitalization ratio is actually another name for the debt-to-capital ratio in most contexts. Some analysts use “capitalization ratio” to refer to the same calculation.

However, variations exist:

- Long-term debt to capitalization uses only long-term debt

- Total debt to capitalization includes all interest-bearing debt

- Financial debt to capitalization excludes operating leases

Always verify which specific components are included in any “capitalization ratio” calculation before making comparisons.

Which Metric to Use When

Use the Debt-to-Capital Ratio when:

- Analyzing capital structure decisions

- Comparing financing strategies across companies

- Evaluating management’s leverage preferences

- Assessing capital allocation efficiency

Use the Debt-to-Equity Ratio when:

- Calculating financial leverage multipliers

- Determining return on equity impacts

- Analyzing shareholder risk exposure

- Compared to industry benchmarks reported in D/E format

Use the Debt Ratio when:

- Assessing overall balance sheet leverage

- Evaluating asset financing methods

- Analyzing total liability exposure

- Comparing companies with different capital structures

Each metric provides a valuable perspective. A comprehensive financial analysis examines multiple leverage measures to build a complete understanding.

Practical Applications and Real-World Examples

The debt-to-capital ratio serves multiple stakeholders making different decisions.

For Investors

Equity investors use this ratio to assess risk-adjusted return potential. Higher leverage amplifies potential returns but increases downside risk during economic contractions.

Investment Decision Framework:

- Calculate the company’s current ratio

- Compare to industry averages

- Analyze trends over 3-5 years

- Evaluate cash flow stability

- Assess management’s capital allocation strategy

A technology company with a 25% debt-to-capital ratio and strong compound growth presents different risk-return characteristics than a utility with a 65% ratio and stable dividends.

Value investors often prefer moderate leverage that enhances returns without creating excessive risk. Growth investors may accept higher ratios if the borrowed capital funds expansion into profitable markets.

For Lenders and Creditors

Banks and bondholders examine debt-to-capital ratios before extending credit. Higher existing leverage indicates reduced capacity to service additional debt.

Credit Analysis Process:

- Below 40%: Strong creditworthiness, low default risk

- 40-60%: Moderate risk, acceptable for stable industries

- 60-75%: Elevated risk, requires strong cash flows

- Above 75%: High risk, limited additional borrowing capacity

Lenders also track ratio trends. A rising debt-to-capital ratio over several quarters signals increasing leverage and potentially deteriorating financial health.

The Altman Z-Score incorporates leverage metrics to predict bankruptcy probability, demonstrating how debt ratios connect to default risk.

For Business Management

Corporate finance teams monitor debt-to-capital ratios to maintain optimal capital structure. This involves balancing the tax benefits of debt financing against financial flexibility and risk.

Strategic Considerations:

When to Increase Debt Ratio:

- Interest rates are historically low

- Tax rates are high (maximizing interest deduction benefits)

- Investment opportunities offer returns exceeding borrowing costs

- Equity markets undervalue the stock (making buybacks attractive)

When to Decrease Debt Ratio:

- Economic uncertainty increases

- Cash flows become less predictable

- Industry faces disruption

- Refinancing risk rises due to debt maturity schedules

Management teams at companies like Apple have strategically increased debt ratios despite massive cash reserves because borrowing costs fell below the after-tax returns on deployed capital.

Real-World Industry Examples (2025)

Utility Sector Example:

A regional electric utility carries $8 billion in long-term debt and $4 billion in equity, producing a 67% debt-to-capital ratio. This high leverage works because:

- Regulated revenue provides predictable cash flows

- Infrastructure assets secure debt at favorable rates

- Tax deductions reduce effective borrowing costs

- Industry average supports this capital structure

Technology Sector Example:

A software company maintains $500 million in debt and $2 billion in equity, yielding a 20% debt-to-capital ratio. This conservative approach reflects:

- Variable revenue from product cycles

- Minimal collateral assets for debt security

- Preference for financial flexibility

- Industry norms favoring equity financing

Manufacturing Sector Example:

An automotive parts manufacturer has $1.2 billion in debt and $1.8 billion in equity, creating a 40% ratio. This moderate leverage balances:

- Cyclical revenue patterns

- Equipment and inventory as collateral

- Working capital requirements

- Competitive return expectations

These examples demonstrate how the same ratio calculation produces vastly different interpretations depending on industry context and business model characteristics.

Understanding capital allocation strategies helps explain why management teams choose different debt-to-capital targets.

Limitations and Considerations

The debt-to-capital ratio provides valuable insight but carries important limitations that affect interpretation.

Accounting Method Variations

Different accounting treatments can distort comparisons between companies:

Operating Leases:

Before 2019, operating leases stayed off balance sheets. New accounting standards (ASC 842/IFRS 16) require capitalization, but older data may exclude significant lease obligations.

Pension Liabilities:

Underfunded pension obligations represent real debt-like commitments but may not appear in traditional debt calculations.

Off-Balance-Sheet Financing:

Special-purpose entities and other structures can hide actual leverage from standard ratio analysis.

Convertible Debt:

Securities that convert to equity create ambiguity; should they count as debt or equity in the calculation?

Always review financial statement footnotes to understand what’s included or excluded from reported debt figures.

Timing and Snapshot Limitations

Balance sheets capture a single moment in time. The debt-to-capital ratio on December 31 may differ substantially from the average throughout the year.

Seasonal Businesses:

Retailers often carry higher debt during inventory build-up periods before peak selling seasons. A year-end calculation might miss this cyclical variation.

Recent Transactions:

Major acquisitions, stock buybacks, or debt refinancings can dramatically shift the ratio immediately after occurring.

Calculate ratios across multiple quarters to identify trends rather than relying on single-point measurements.

Industry and Economic Context

The same ratio carries different implications across contexts:

During Economic Expansion:

- Higher debt ratios appear manageable

- Revenue growth supports debt service

- Credit remains readily available

- Risk tolerance increases

During the Recession:

- Moderate debt ratios become concerning

- Revenue declines stress cash flows

- Refinancing becomes difficult

- Risk aversion dominates

A 55% debt-to-capital ratio signals prudent leverage in 2019, but potential distress in 2020 during pandemic-driven revenue collapses.

Market Value vs. Book Value

The standard formula uses book values from the balance sheet. Market values can differ substantially:

Equity Market Value:

Public company equity trades at market capitalization (share price × shares outstanding), often far above or below book equity value.

Debt Market Value:

Bond prices fluctuate with interest rates, creating market values different from face values on balance sheets.

Some analysts calculate market-value debt-to-capital ratios using current market prices for both debt and equity. This approach better reflects real-time investor perceptions but introduces volatility from daily price movements.

Complementary Metrics Required

No single ratio tells the complete financial story. Comprehensive analysis requires examining:

- Current ratio and quick ratio for liquidity

- Interest coverage ratios for debt service capacity

- Cash conversion cycle for working capital efficiency

- Return on invested capital for capital allocation effectiveness

- EBITDA multiples for valuation context

The debt-to-capital ratio reveals capital structure but must be interpreted alongside operational performance, cash generation, and industry dynamics.

How to Improve or Optimize Debt-to-Capital Ratio

Companies actively manage their debt-to-capital ratios through deliberate financial strategies.

Reducing the Ratio (Deleveraging)

Method 1: Debt Repayment

Use excess cash flow or asset sales to pay down outstanding debt. This directly reduces the numerator while maintaining equity levels.

Impact: Immediate ratio reduction, improved creditworthiness, reduced interest expense

Considerations: Opportunity cost of deploying cash elsewhere, potential prepayment penalties

Method 2: Equity Issuance

Sell new shares to raise capital, then use proceeds to repay debt or simply increase the equity base.

Impact: Increases denominator (total capital) while potentially reducing numerator (if proceeds repay debt)

Considerations: Shareholder dilution, market timing, issuance costs

Method 3: Retained Earnings Accumulation

Generate profits and retain them rather than distributing dividends. Retained earnings increase equity over time.

Impact: Gradual ratio improvement through organic equity growth

Considerations: Shareholder expectations for dividends, time required for meaningful impact

The deleveraging process requires balancing speed against financial flexibility and shareholder returns.

Increasing the Ratio (Adding Leverage)

Method 1: Debt-Funded Growth

Borrow capital to fund expansion, acquisitions, or capital expenditures that generate returns exceeding borrowing costs.

Impact: Increases numerator, potentially increases total capital if equity remains constant

Considerations: Interest rate environment, return on invested capital, refinancing risk

Method 2: Share Repurchases

Buy back company stock using borrowed funds or cash reserves, reducing total equity.

Impact: Reduces denominator (equity), increases numerator (if debt-funded)

Considerations: Stock valuation, alternative uses of capital, signaling effects

Method 3: Dividend Recapitalization

Borrow money specifically to pay special dividends to shareholders, increasing debt while reducing retained earnings.

Impact: Increases debt, reduces equity through earnings distribution

Considerations: Typically used in private equity contexts, it can stress the balance sheet

Finding the Optimal Balance

The “right” debt-to-capital ratio depends on:

- Industry capital intensity and norms

- Revenue stability and predictability

- Growth opportunities and capital requirements

- Tax rates and interest deductibility benefits

- Management risk tolerance

- Shareholder return expectations

Companies continuously adjust capital structure through normal operations and strategic decisions. The optimal ratio evolves with business conditions, market opportunities, and competitive dynamics.

Financial theory suggests an optimal capital structure exists where the marginal benefit of debt tax shields equals the marginal cost of financial distress risk. In practice, management targets a range rather than a precise number.

Debt-to-Capital Ratio Calculator

Calculate your company’s financial leverage instantly

Conclusion: Mastering the Math Behind Capital Structure

The debt-to-capital ratio translates complex balance sheet data into a single, actionable metric that reveals how companies fund operations and growth.

This formula: Total Debt ÷ (Total Debt + Shareholders’ Equity) quantifies the fundamental financing choice every business faces: borrow or raise equity.

Understanding this ratio means understanding financial leverage, risk management, and the trade-offs between debt’s tax advantages and its mandatory repayment obligations.

Key principles to remember:

The ratio measures what percentage of capital comes from borrowed funds versus owner investment. A 0.50 ratio means 50% debt funding and 50% equity funding.

Industry context determines appropriate leverage levels. Capital-intensive businesses with stable cash flows safely carry 60-70% ratios, while asset-light companies with variable revenues typically maintain 20-40% ratios.

Higher ratios amplify both returns and risks. Debt magnifies equity returns during growth but accelerates losses during downturns.

No single ratio tells the complete story. Comprehensive financial analysis examines debt-to-capital alongside liquidity metrics, profitability measures, and cash flow generation.

Actionable next steps:

- Calculate the ratio for companies you own or follow using their most recent balance sheets

- Compare results to industry averages to identify outliers requiring deeper investigation

- Track trends over 3-5 years to understand management’s capital structure strategy

- Evaluate alongside cash flow metrics like debt service coverage ratio to assess repayment capacity

- Consider the economic environment when interpreting results—the same ratio carries different implications during expansion versus recession

The math behind money reveals itself through metrics like the debt-to-capital ratio. Master this calculation, understand its context, and apply it consistently to build wealth through evidence-based investing and sound financial decision-making.

Financial literacy begins with understanding the numbers that drive business performance and investment returns. The debt-to-capital ratio provides a clear window into capital structure decisions that ultimately determine long-term value creation.

References

[1] Corporate Finance Institute. “Debt-to-Capital Ratio.” CFI Education. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/

[2] CFA Institute. “Capital Structure Analysis.” CFA Program Curriculum. https://www.cfainstitute.org/

[3] Investopedia. “Understanding Capitalization Ratios.” Financial Ratio Analysis. https://www.investopedia.com/

[4] Federal Reserve. “Financial Stability Report: Corporate Leverage Metrics.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/

[5] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “How to Read a 10-K/10-Q.” Investor Publications. https://www.sec.gov/

[6] Financial Accounting Standards Board. “ASC 842: Lease Accounting Standards.” FASB Codification. https://www.fasb.org/

[8] Morningstar. “Financial Health Metrics for Equity Analysis.” Investment Research. https://www.morningstar.com/

Frequently Asked Questions About Debt-to-Capital Ratio

What’s the difference between debt-to-capital and debt-to-equity?

The debt-to-capital ratio expresses debt as a percentage of total capital (debt + equity), while debt-to-equity shows the ratio between these two components. Debt-to-capital cannot exceed 100%, but debt-to-equity can be any positive number. A 60% debt-to-capital ratio equals a 1.5 debt-to-equity ratio.

Is a higher or lower debt-to-capital ratio better?

Neither is universally better—optimal ratios depend on industry, business model, and economic conditions. Capital-intensive industries with stable cash flows (utilities, infrastructure) function well with 60–70% ratios. Asset-light businesses with variable revenues (technology, services) typically maintain 20–40% ratios. The best ratio balances the tax benefits of debt against financial flexibility and risk tolerance.

Where do I find the numbers to calculate this ratio?

All required information appears on the company balance sheet, found in quarterly (10-Q) or annual (10-K) reports filed with the SEC. Look for total debt or sum short-term and long-term debt line items. Find total shareholders’ equity in the equity section. Public company financial statements are available for free on SEC.gov or the company’s investor relations pages.

Can the debt-to-capital ratio be negative?

Yes, but only when shareholder equity is negative—meaning accumulated losses exceed invested capital and the company has negative book value. This signals severe financial distress. In this situation, the ratio becomes mathematically unstable and loses interpretive value. Negative equity companies face bankruptcy risk and require deeper analysis.

How often should I calculate this ratio?

For investment analysis, calculate quarterly using each period’s balance sheet to identify trends. Single-point calculations can be misleading due to seasonal or one-time events. Track the ratio across at least 3–5 years to understand directional changes and management’s capital structure decisions. Compare to historical averages and industry benchmarks.

Does this ratio predict bankruptcy?

The debt-to-capital ratio alone doesn’t predict bankruptcy, but very high ratios (above 80%) combined with declining profitability or cash flows indicate elevated default risk. Bankruptcy models like the Altman Z-Score use leverage metrics alongside liquidity and profitability measures. This ratio signals financial risk but must be evaluated with interest coverage and cash flow health.

What ratio do banks prefer when lending?

Banks typically prefer debt-to-capital ratios below 60% for most corporate borrowers. Asset-based lending may accept higher levels. Lenders analyze trends as well—rising ratios raise concerns even if still below thresholds. Many loan agreements include covenants specifying maximum allowable debt-to-capital ratios.