A mutual fund is an investment vehicle that pools money from multiple investors to purchase a diversified portfolio of stocks, bonds, or other securities. Professional fund managers make investment decisions on behalf of shareholders, providing access to diversified portfolios that would be difficult for individual investors to build alone.

Mutual funds serve as one of the most accessible entry points into investing. They allow beginners to participate in the stock and bond markets without requiring extensive financial knowledge or large amounts of capital. The pooled structure spreads risk across dozens or hundreds of securities while professional management handles the daily investment decisions.

Understanding how mutual funds work, their cost structures, and their limitations helps investors make informed decisions about whether these vehicles align with their financial goals. This guide breaks down the mechanics, types, fees, and risks associated with mutual fund investing. This article is part of our comprehensive investing guide.

Key Takeaways

- Mutual funds pool investor capital to create diversified portfolios managed by professional investment teams

- Net Asset Value (NAV) determines share price, calculated once daily after market close based on total portfolio value

- Expense ratios and load fees significantly impact long-term returns, with costs ranging from 0.05% to 2%+ annually

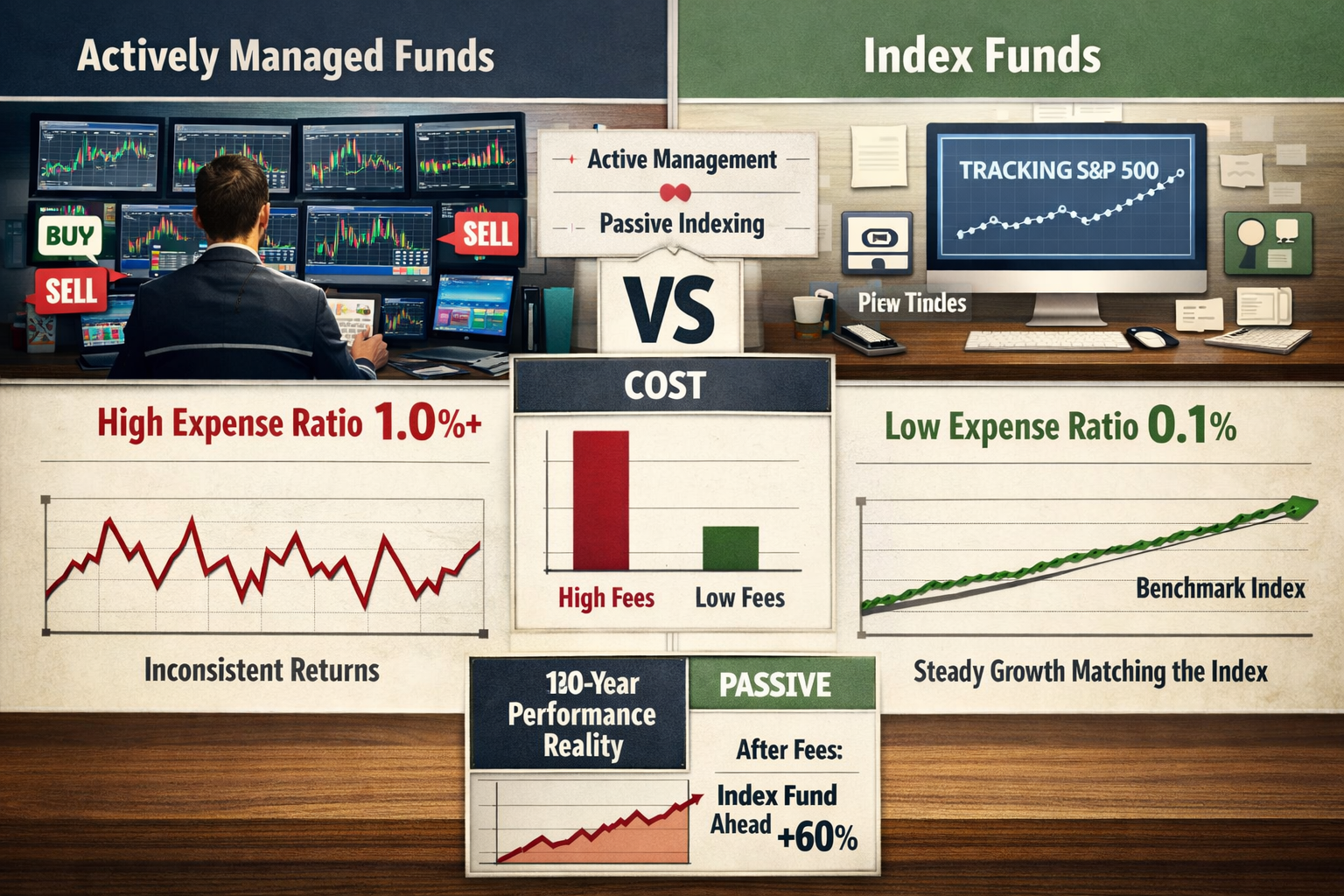

- Index funds typically outperform actively managed funds after fees over 10+ year periods

- Tax efficiency favors ETFs over mutual funds due to structural differences in how capital gains are distributed

What Is a Mutual Fund?

A mutual fund represents a professionally managed investment portfolio funded by multiple investors who purchase shares in the fund. Each share represents proportional ownership of the fund’s entire holdings.

When you invest in a mutual fund, you buy shares at the fund’s Net Asset Value (NAV). The NAV equals the total value of all securities in the portfolio minus liabilities, divided by the number of outstanding shares. This calculation occurs once daily after markets close.

Fund managers make all buying and selling decisions according to the fund’s stated investment objective. An equity growth fund manager selects stocks expected to appreciate. A bond fund manager chooses fixed-income securities based on credit quality and yield targets.

The fund company charges fees for management services, administrative costs, and sometimes sales commissions. These expenses reduce the returns investors receive, making fee comparison essential when selecting funds.

How Mutual Funds Work

The mutual fund structure creates a cycle of capital pooling, professional investment, and return distribution.

Step 1: Capital Collection

Investors purchase fund shares directly from the fund company or through brokerage accounts. The fund accepts new investments continuously, issuing new shares at the current NAV. Unlike stocks that trade between investors, mutual fund shares are bought from and sold back to the fund itself.

Step 2: Portfolio Construction

Fund managers deploy collected capital according to the fund’s investment strategy. An S&P 500 index fund purchases all 500 stocks in proportion to their market capitalization. An actively managed technology fund selects individual tech stocks based on research and analysis.

Step 3: Daily Valuation

The fund calculates NAV each business day after market close. If a fund holds $100 million in securities and has 10 million shares outstanding, the NAV equals $10.00 per share. Investors who submit purchase or redemption orders during the day receive this closing NAV price.

Step 4: Return Distribution

Mutual funds generate returns through three mechanisms:

- Dividend income from stocks or interest from bonds is distributed to shareholders quarterly or annually

- Capital gains when the fund sells securities at a profit are distributed annually

- NAV appreciation as the underlying securities increase in value

Example with numbers:

An investor purchases 100 shares at $50 NAV, investing $5,000. After one year, the fund pays $0.50 per share in dividends ($50 total) and $1.00 per share in capital gains ($100 total). The NAV rises to $53. Total return equals dividends ($50) + capital gains ($100) + NAV appreciation ($300) = $450, or 9% on the initial investment.

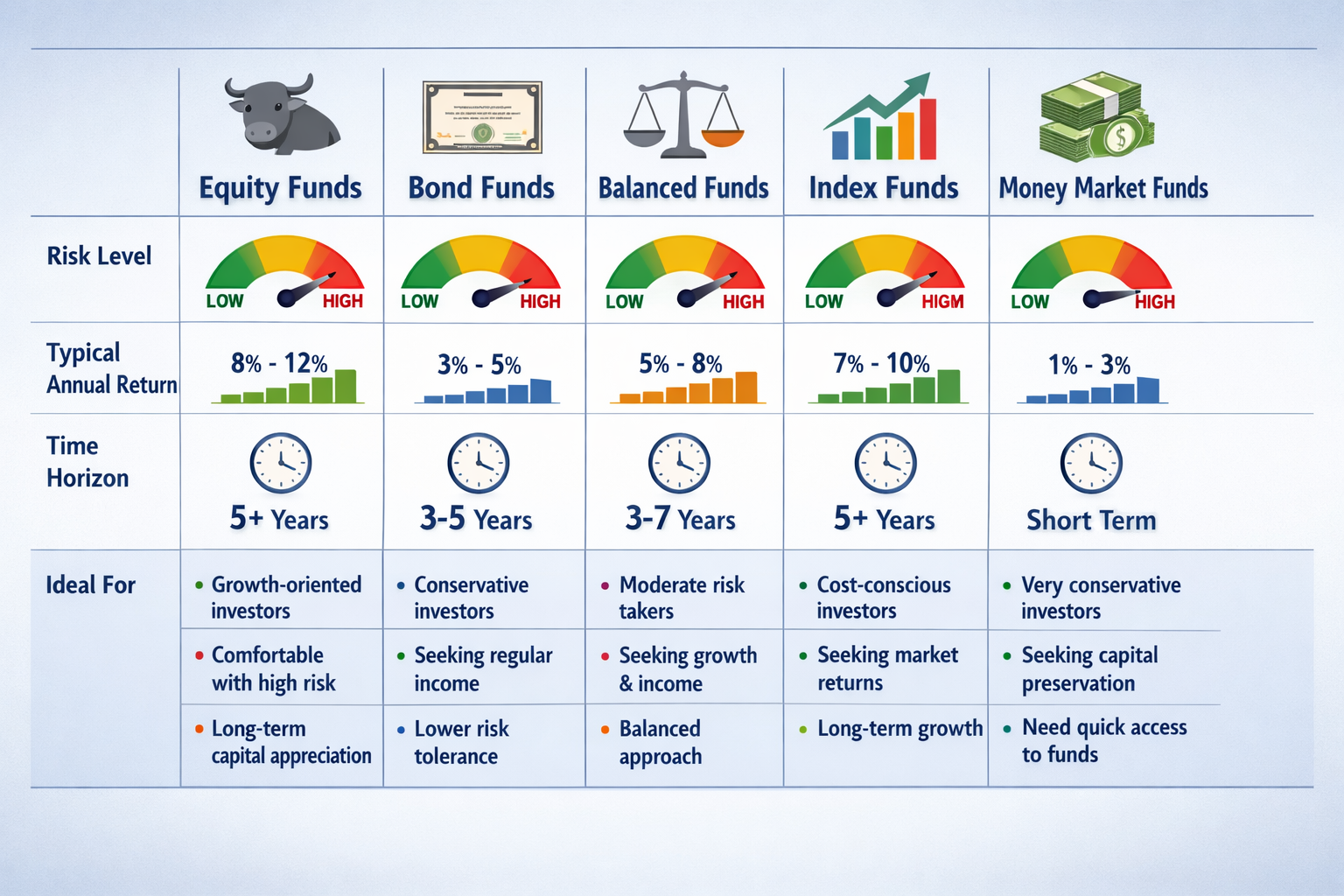

Types of Mutual Funds

Mutual funds are divided into categories based on asset class, investment strategy, and risk profile.

Equity Mutual Funds

Equity funds invest primarily in stocks, offering the highest growth potential with corresponding volatility. These funds are subdivided by company size (large-cap, mid-cap, small-cap), geography (domestic, international, emerging markets), or investment style (growth, value, blend).

Risk level: High

Typical use case: Long-term wealth building, retirement accounts

Time horizon: 10+ years

Growth-focused equity funds target companies expected to increase earnings rapidly. Value funds seek underpriced stocks trading below intrinsic value. Blend funds combine both approaches.

Bond Mutual Funds

Bond funds hold fixed-income securities issued by governments, municipalities, or corporations. They provide regular income through interest payments with lower volatility than stocks.

Risk level: Low to moderate

Typical use case: Income generation, portfolio stabilization

Time horizon: 3-10 years

Corporate bond funds offer higher yields but carry credit risk. Government bond funds provide safety but lower returns. Municipal bond funds generate tax-free income for investors in high tax brackets.

Balanced / Hybrid Funds

Balanced funds maintain a mix of stocks and bonds within a single portfolio, typically following a fixed allocation like 60% stocks and 40% bonds. This structure provides growth potential with built-in downside protection.

Risk level: Moderate

Typical use case: One-fund portfolio solution, conservative growth

Time horizon: 5-15 years

Target-date retirement funds represent a popular hybrid category. These funds automatically adjust the stock-to-bond ratio as the target retirement date approaches, becoming more conservative over time.

Index Mutual Funds

Index funds replicate the performance of a specific market index by holding all or a representative sample of the index’s securities. The S&P 500 index fund owns the same 500 stocks in identical proportions as the index itself.

Risk level: Matches underlying index

Typical use case: Low-cost market exposure, core portfolio holdings

Time horizon: 10+ years

Index funds require minimal management since they simply track an index rather than attempting to beat it. This passive approach results in significantly lower fees compared to actively managed funds. For more on this strategy, see our guide on the best index funds.

Money Market Funds

Money market funds invest in short-term debt securities like Treasury bills, commercial paper, and certificates of deposit. They aim to maintain a stable $1.00 NAV while generating modest interest income.

Risk level: Very low

Typical use case: Cash parking, emergency funds

Time horizon: Less than 1 year

These funds serve as alternatives to savings accounts, offering slightly higher yields with high liquidity. However, money market funds lack FDIC insurance, creating minimal but non-zero risk.

| Fund Type | Primary Assets | Risk Level | Typical Return* | Best For | Time Horizon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equity Funds | Stocks | High | 8-10% | Growth, retirement | 10+ years |

| Bond Funds | Fixed income | Low-Moderate | 3-5% | Income, stability | 3-10 years |

| Balanced Funds | Stocks + Bonds | Moderate | 5-7% | Diversification | 5-15 years |

| Index Funds | Market index | Varies | Matches index | Low-cost exposure | 10+ years |

| Money Market | Short-term debt | Very Low | 2-4% | Cash management | <1 year |

*Historical averages; not guaranteed future performance

Actively Managed vs Index Mutual Funds

The fundamental difference between active and passive mutual funds lies in how managers make investment decisions and how much they charge for their services.

Decision-Making Approach

Actively managed funds employ research teams who analyze companies, economic trends, and market conditions to select securities they believe will outperform. Fund managers buy and sell holdings based on their forecasts and valuations.

Index funds follow predetermined rules to match a benchmark. When Apple’s market capitalization increases, an S&P 500 index fund automatically increases its Apple allocation proportionally. No judgment or prediction enters the process.

Cost Structure

Active management requires expensive resources: analyst salaries, research subscriptions, trading costs, and marketing. These expenses translate to higher expense ratios, typically ranging from 0.50% to 1.50% annually.

Index funds operate with minimal overhead since they simply replicate an index. Expense ratios often fall below 0.10%, with some large funds charging as little as 0.03%.

Performance Reality

Over 10-year periods, approximately 85% of actively managed U.S. equity funds underperform their benchmark index after fees [1]. The math works against active managers: they must outperform by more than their fee differential just to match index returns.

A fund charging 1.00% must beat the market by 1.00% annually just to tie an index fund charging 0.10%. Over 30 years, this fee difference compounds dramatically. A $10,000 investment growing at 8% annually becomes $100,627. The same investment with 1% in annual fees becomes $76,123—a $24,504 difference caused entirely by fees.

The evidence supports index investing for most investors, particularly those building wealth through consistent contributions over decades. Active funds occasionally outperform, but identifying future winners proves nearly impossible.

Mutual Fund Comparison Table

Mutual Fund Fees & Expenses

Fee structures directly impact long-term wealth accumulation. Understanding each cost component enables accurate fund comparison.

Expense Ratio

The expense ratio represents the annual percentage of assets deducted for fund operations. A 1.00% expense ratio on a $10,000 investment costs $100 per year. This fee comes out automatically—you never see a bill, but your returns decrease accordingly.

Expense ratios cover:

- Management fees paid to portfolio managers

- Administrative costs for recordkeeping and customer service

- 12b-1 marketing and distribution fees (if applicable)

Load vs No-Load Funds

Load funds charge sales commissions when you buy (front-end load) or sell (back-end load) shares. A 5% front-end load on a $10,000 investment means $500 goes to the broker and only $9,500 gets invested.

No-load funds charge no sales commissions. You invest the full amount. Given that load funds don’t demonstrate better performance than no-load alternatives, loads simply reduce returns without providing value.

Management Fees

Management fees compensate the portfolio managers and research team. These fees comprise the largest component of the expense ratio, typically ranging from 0.05% for index funds to 1.00%+ for actively managed funds.

Turnover Costs

When funds buy and sell securities, they incur trading costs: brokerage commissions, bid-ask spreads, and market impact costs. High-turnover funds (those replacing more than 100% of holdings annually) generate substantial hidden costs not captured in the expense ratio.

Frequent trading also triggers more taxable capital gains distributions, creating tax drag in addition to trading costs.

Fee Impact Example

Consider two mutual funds with identical 8% gross returns before fees:

Fund A (Index): 0.10% expense ratio

Net return: 7.90% annually

$10,000 grows to $103,996 over 30 years

Fund B (Active): 1.25% expense ratio

Net return: 6.75% annually

$10,000 grows to $66,144 over 30 years

The 1.15% fee difference costs $37,852 in lost wealth—nearly 4x the initial investment. This mathematical reality explains why low-cost index funds dominate long-term wealth-building strategies.

Benefits of Investing in Mutual Funds

Mutual funds provide specific advantages that make them suitable for certain investors and situations.

Instant Diversification

A single mutual fund share provides exposure to dozens or hundreds of securities. This diversification reduces company-specific risk. If one holding collapses, it represents only a small percentage of the total portfolio.

Professional Management

Fund managers handle security selection, portfolio rebalancing, and risk management. Investors delegate these technical decisions to experienced professionals rather than researching individual stocks themselves.

Accessibility

Many mutual funds accept initial investments as low as $1,000, with subsequent purchases starting at $100. This low barrier enables beginning investors to access diversified portfolios without accumulating large amounts of capital first.

Automatic Investing

Most fund companies offer automatic investment plans that transfer money from checking accounts on a set schedule. This automation facilitates dollar-cost averaging, where regular investments purchase more shares when prices fall and fewer when prices rise.

Regulatory Oversight

The Securities and Exchange Commission regulates mutual funds, requiring disclosure of holdings, fees, and risks. This transparency provides investor protection absent from many alternative investments.

Liquidity

Mutual fund shares can be sold on any business day at the NAV price. Investors access their money within 1-3 business days, providing flexibility for changing financial needs.

Risks & Drawbacks

Mutual funds carry inherent limitations and risks that investors must understand before committing capital.

Market Risk

Mutual funds fluctuate with market conditions. Equity funds decline during stock market downturns. Bond funds lose value when interest rates rise. No fund manager can eliminate systematic market risk, regardless of skill level.

The 2008 financial crisis saw the average U.S. equity fund decline 38%. Diversification within the fund did not protect against a broad market collapse.

Manager Risk

Actively managed funds depend on the manager’s skill and decision-making. Poor security selection, bad market timing, or excessive risk-taking can produce returns far below the benchmark.

Manager turnover creates additional uncertainty. When a successful manager leaves, the fund’s strategy and performance often change dramatically.

Fee Drag

High expense ratios and load fees create a permanent headwind against returns. Each percentage point in fees requires the fund to outperform by that amount just to match lower-cost alternatives.

Over multi-decade periods, fee drag compounds into six-figure wealth differences, as demonstrated in the earlier calculation.

Tax Inefficiency

Mutual funds distribute capital gains to shareholders annually, creating taxable events even when you don’t sell shares. Active funds with high turnover generate substantial short-term capital gains taxed at ordinary income rates.

You pay taxes on these distributions regardless of whether you reinvest them or take cash. This structure makes mutual funds less tax-efficient than ETFs, which rarely distribute capital gains due to their different creation/redemption mechanism.

Lack of Intraday Trading

Mutual funds trade once daily at the closing NAV. You cannot respond to intraday market movements or execute trades at specific price points. This limitation matters less for long-term investors but frustrates those wanting tactical control.

Minimum Investment Requirements

While lower than direct stock investing, mutual fund minimums ($1,000-$3,000 typically) can still present barriers. Some premium funds require $10,000 or more for an initial purchase.

Understanding these risks enables realistic expectations. Mutual funds serve specific purposes well, but don’t represent perfect investment vehicles for all situations. For more on managing investment risk, see our guide on portfolio diversification.

Mutual Funds vs ETFs

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) share similarities with mutual funds but differ in structure, trading, costs, and tax treatment.

| Feature | Mutual Funds | ETFs |

|---|---|---|

| Trading | Once daily at NAV | Continuous during market hours |

| Pricing | End-of-day NAV | Real-time market price |

| Minimum Investment | $1,000-$3,000 typical | 1 share (often $50-$500) |

| Expense Ratios | 0.10%-1.50% | 0.03%-0.75% |

| Tax Efficiency | Lower (annual distributions) | Higher (in-kind redemptions) |

| Automatic Investing | Widely available | Limited availability |

| Fractional Shares | Yes (dollar-based) | Limited (broker-dependent) |

| Commissions | Usually none | Often none (broker-dependent) |

When Mutual Funds Make Sense

Mutual funds work better for:

- Automatic investment plans with fixed dollar amounts

- Retirement accounts with regular contributions

- Investors who prefer dollar-based investing over share-based

- Situations where intraday pricing creates no value

When ETFs Make Sense

ETFs provide advantages for:

- Tax-efficient investing in taxable accounts

- Lower expense ratios on identical strategies

- Intraday trading flexibility

- Smaller initial investments (single share minimum)

The choice between mutual funds and ETFs often depends less on performance potential and more on practical factors: account type, investment frequency, and tax situation. For more details, see our comparison of exchange-traded funds.

Who Should Invest in Mutual Funds?

Mutual funds suit specific investor profiles and situations better than others.

Ideal Candidates

Beginning Investors

Those new to investing benefit from professional management and instant diversification. Mutual funds remove the need to research individual securities while providing market exposure.

Retirement Account Holders

401(k) plans typically offer mutual funds as primary investment options. The tax-deferred nature of retirement accounts eliminates the tax efficiency advantage of ETFs, making mutual funds equally suitable.

Automatic Investors

Investors who dollar-cost average through regular contributions find mutual funds more convenient than ETFs. Most fund companies facilitate automatic transfers and purchases without trading commissions.

Long-Term Buy-and-Hold Investors

Those planning to hold investments for decades care less about intraday pricing or tax efficiency in the short term. Low-cost index mutual funds serve this group effectively.

Hands-Off Investors

People who prefer delegating investment decisions to professionals rather than actively managing portfolios find mutual funds aligned with this preference.

Who Should Consider Alternatives

Tax-Sensitive Investors

Those investing in taxable accounts with high tax brackets benefit more from ETF tax efficiency. The annual capital gains distributions from mutual funds create unnecessary tax drag.

Cost-Conscious Investors

While low-cost index mutual funds exist, ETFs on identical strategies often charge even lower expense ratios. A 0.03% ETF beats a 0.10% mutual fund on the same index.

Active Traders

Investors who adjust positions frequently need intraday trading capability. Mutual funds’ once-daily pricing creates operational limitations for tactical approaches.

Small Account Holders

Those starting with less than $1,000 may find ETF single-share minimums more accessible than mutual fund account minimums.

The decision hinges on individual circumstances rather than universal rules. Many investors use both: mutual funds in retirement accounts and ETFs in taxable accounts.

How to Start Investing in Mutual Funds

The process of investing in mutual funds follows a straightforward sequence.

Step 1: Choose Account Type

Decide between taxable brokerage accounts and tax-advantaged retirement accounts (IRA, 401(k)). Retirement accounts provide tax benefits but restrict access until age 59½. Taxable accounts offer flexibility but generate annual tax obligations.

Step 2: Select a Brokerage or Fund Company

Major brokerages (Vanguard, Fidelity, Schwab) offer thousands of mutual funds, including their own low-cost index funds. Employer retirement plans limit choices to a pre-selected menu.

Step 3: Identify Fund Category

Determine appropriate asset allocation based on time horizon and risk tolerance. Longer time horizons support higher stock allocations. Shorter horizons require more bonds and stable assets.

A common starting allocation:

- 70-80% stock index funds for growth

- 20-30% bond index funds for stability

Step 4: Compare Expense Ratios

Within each category, prioritize funds with the lowest expense ratios. A total stock market index fund charging 0.04% provides essentially identical holdings to one charging 0.20%, but costs 80% less.

Step 5: Invest Regularly

Establish automatic contributions aligned with your budget. Consistent investing matters more than perfect timing. Regular purchases at varying prices smooth out market volatility through dollar-cost averaging.

Step 6: Rebalance Annually

Once per year, adjust holdings back to target allocations. If stocks outperform and grow from 70% to 80% of the portfolio, sell some stock funds and buy bond funds to restore the 70/30 balance.

Starting with simple, low-cost index funds in a tax-advantaged account provides a solid foundation. Complexity adds little value for most investors.

Tax Treatment of Mutual Funds

Mutual fund taxation creates obligations that investors must understand to avoid surprises.

Capital Gains Distributions

When fund managers sell securities at a profit, they realize capital gains. Mutual funds must distribute at least 95% of these gains to shareholders annually to maintain tax-advantaged status.

You receive these distributions as taxable income even if you reinvest them to purchase more shares. Short-term capital gains (from securities held less than one year) are taxed as ordinary income. Long-term capital gains receive preferential tax rates (0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on income).

High-turnover active funds generate more short-term gains, creating higher tax bills. Index funds with minimal trading distribute primarily long-term gains or no gains at all.

Dividend Distributions

Mutual funds pass through dividend income from stocks and interest from bonds. Qualified dividends from stocks receive preferential tax treatment (same rates as long-term capital gains). Bond interest and non-qualified dividends are taxed as ordinary income.

Tax-Advantaged Accounts

Holding mutual funds in IRAs, 401(k)s, or other retirement accounts defers all taxes on distributions and capital gains. You pay taxes only when withdrawing money in retirement, eliminating the annual tax drag.

This tax shelter makes mutual funds equally efficient as ETFs within retirement accounts, removing one of ETFs’ primary advantages.

Tax-Loss Harvesting Limitations

When you sell mutual fund shares at a loss, you can use that loss to offset capital gains or deduct up to $3,000 against ordinary income. However, the wash sale rule prohibits claiming a loss if you purchase substantially identical securities within 30 days before or after the sale.

Understanding tax implications helps optimize account location decisions: hold tax-inefficient assets in retirement accounts and tax-efficient assets in taxable accounts. For more on tax-advantaged strategies, see our guide on capital gains tax.

Common Mutual Fund Mistakes

Investors repeatedly make predictable errors that undermine returns.

Chasing Past Performance

Mutual funds showing strong recent returns attract investor capital. However, past performance provides no guarantee of future results. Academic research shows that yesterday’s top-performing funds often become tomorrow’s underperformers [3].

Investors who chase performance buy high (after strong runs) and sell low (after disappointing periods), the opposite of a wealth-building strategy.

Ignoring Expense Ratios

A 1% expense ratio difference seems small in isolation. Over 30 years, it compounds into a 30%+ wealth difference. Many investors focus on returns while overlooking the fees that silently erode those returns.

Always compare expense ratios within the same fund category. Choose the lowest-cost option when holdings are substantially similar.

Over-Diversifying

Owning 15 mutual funds doesn’t provide 15x the diversification benefit. Many funds hold overlapping securities. An investor might own five large-cap growth funds that all hold Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon as top positions.

This false diversification creates complexity without additional risk reduction. A simple three-fund portfolio (total stock market, total international stock, total bond market) provides complete diversification.

Frequent Trading

Mutual funds work best as long-term holdings. Selling funds to chase trends or time the market typically destroys returns through poor timing, taxes, and potential redemption fees.

Market timing requires being right twice: when to sell and when to buy back. Few investors execute both decisions correctly with consistency.

Ignoring Tax Consequences

Selling mutual funds in taxable accounts triggers capital gains taxes. Investors who trade frequently or fail to consider tax implications surrender significant returns to the IRS unnecessarily.

Tax-aware investing—holding funds long-term, harvesting losses strategically, and using tax-advantaged accounts—preserves more wealth than ignoring tax efficiency.

Related Guides

For a complete understanding of building an investment portfolio, explore our comprehensive investing guide.

To compare mutual funds with their closest alternative, read our detailed analysis of best ETFs to buy.

Mutual Fund Fee Impact Calculator

See how expense ratios affect your wealth over time

Low-Cost Fund

High-Cost Fund

Wealth Lost to Higher Fees

That’s 57% more wealth with the low-cost fund

Conclusion

Mutual funds provide accessible, diversified investment vehicles suitable for beginning investors and retirement accounts. Their pooled structure enables professional management and instant diversification with relatively low minimum investments.

The choice between actively managed and index mutual funds favors low-cost index funds for most investors. The math of fees compounds relentlessly—a 1% expense ratio difference costs tens of thousands of dollars over investment lifetimes.

Understanding fee structures, tax implications, and the limitations of mutual funds enables informed decisions about when these vehicles serve your goals and when alternatives like ETFs provide better solutions.

For a complete beginner’s roadmap to building wealth through investing, see our comprehensive investing basics.

References

[1] S&P Dow Jones Indices. “SPIVA U.S. Scorecard.” S&P Global, 2025.

[2] Morningstar. “2008 Fund Performance Analysis.” Morningstar Research, 2009.

[3] Carhart, Mark M. “On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance.” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 52, No. 1, 1997.

Disclaimer

This article provides educational information about mutual funds and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. Mutual fund investments carry risk, including potential loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Expense ratios, tax treatment, and fund performance vary by specific fund and individual circumstances.

Consult a qualified financial advisor, tax professional, or investment adviser before making investment decisions. The Rich Guy Math provides data-driven financial education but does not recommend specific mutual funds, investment strategies, or asset allocations for individual situations.

All examples use hypothetical scenarios for illustration purposes only. Actual investment results will differ based on market conditions, fund selection, fees, taxes, and timing.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that explains the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and risk management. With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based investing, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable insights for beginner and intermediate investors. His work focuses on helping readers understand how money actually works through numbers, logic, and empirical research rather than hype or speculation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are mutual funds safe?

Mutual funds carry market risk, but they are regulated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and are designed to reduce company-specific risk through diversification.

By investing in dozens or even hundreds of securities, mutual funds are generally safer than owning individual stocks. However, they are not risk-free, and their value can decline during market downturns.

Can you lose money in mutual funds?

Yes. Mutual funds fluctuate with market conditions, and losses are possible.

- Stock (equity) mutual funds can decline 30–50% during severe bear markets

- Bond funds can lose value when interest rates rise

- Money market funds aim to maintain stability but are not FDIC insured

Losses are usually temporary for diversified, long-term investors, but short-term volatility should be expected.

What is a good expense ratio for a mutual fund?

A good expense ratio depends on the fund type:

- Index mutual funds: Below 0.20%, with many strong options under 0.10%

- Actively managed funds: Typically 0.60%–1.00%

Research consistently shows that lower expense ratios lead to higher long-term returns, making low-cost index funds the preferred choice for most investors.

What is the difference between a mutual fund and an index fund?

Index funds are a type of mutual fund. The key difference lies in how investments are selected.

- Index funds: Passively track a market index like the S&P 500

- Actively managed mutual funds: Managers select investments in an attempt to outperform the market

Index funds usually charge lower fees and often outperform active funds over long periods after costs.

Are mutual funds good for beginners?

Yes. Mutual funds—especially low-cost index funds—are well suited for beginners.

They offer instant diversification, professional management, automatic investing options, and relatively low minimum investment requirements, making them easy to use for long-term wealth building.

How are mutual funds different from stocks?

Stocks represent ownership in a single company, while mutual funds pool investor money to own many securities at once.

- Stocks trade throughout the day at market prices

- Mutual funds trade once per day at net asset value (NAV)

- Stocks require individual research and monitoring

- Mutual funds delegate investment decisions to fund managers

Do mutual funds pay dividends?

Yes. Mutual funds distribute income earned from dividends on stocks and interest from bonds to shareholders.

Distributions typically occur quarterly or annually. Investors can choose to receive the cash or automatically reinvest dividends to buy additional fund shares, allowing compounding over time.