← Back to Budgeting and Saving

Most people fail at budgeting not because they lack discipline, but because they’re using a system designed to fail.

The math behind money reveals a simple truth: a working budget isn’t about restriction—it’s about intentional allocation. When income flows into predetermined categories based on your actual priorities and spending patterns, financial stress decreases while savings increase. This cause-and-effect relationship forms the foundation of sustainable wealth building, yet 65% of Americans don’t track their spending at all.

Learning how to create a budget transforms financial chaos into clarity. This comprehensive guide provides a step-by-step framework that accounts for real-life variables, irregular income, unexpected expenses, and human behavior, rather than theoretical perfection. The result: a sustainable system that adapts to your life instead of forcing your life to adapt to arbitrary rules.

Key Takeaways

A working budget allocates every dollar intentionally rather than restricting spending; spending the difference determines long-term success

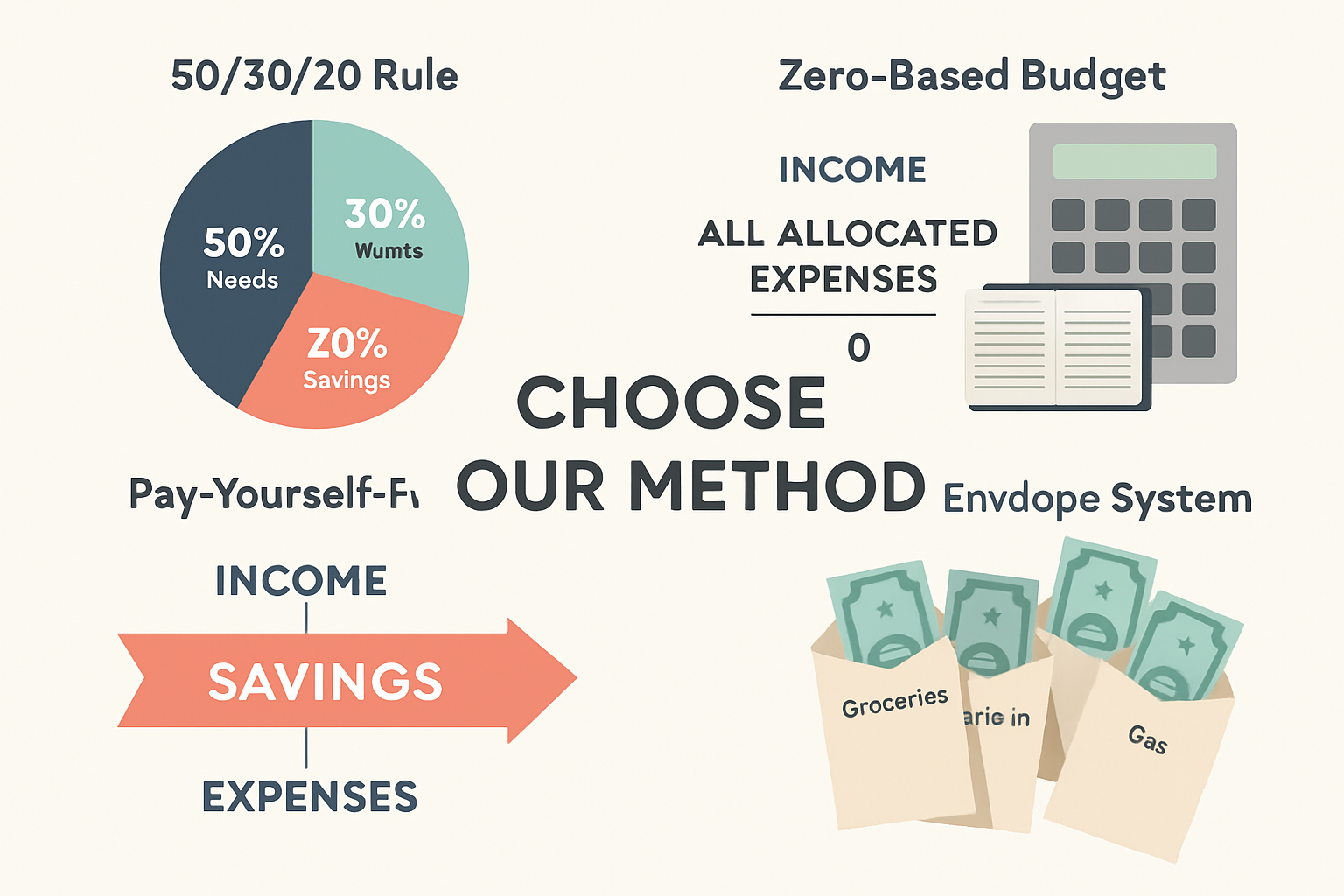

Choose a budgeting method that matches your income pattern and personality. 50/30/20, zero-based, or pay-yourself-first approaches each solve different problems

Automation eliminates 80% of budgeting friction by removing manual decisions from recurring expenses and savings

Weekly 10-minute reviews prevent monthly disasters, small course corrections beat major overhauls

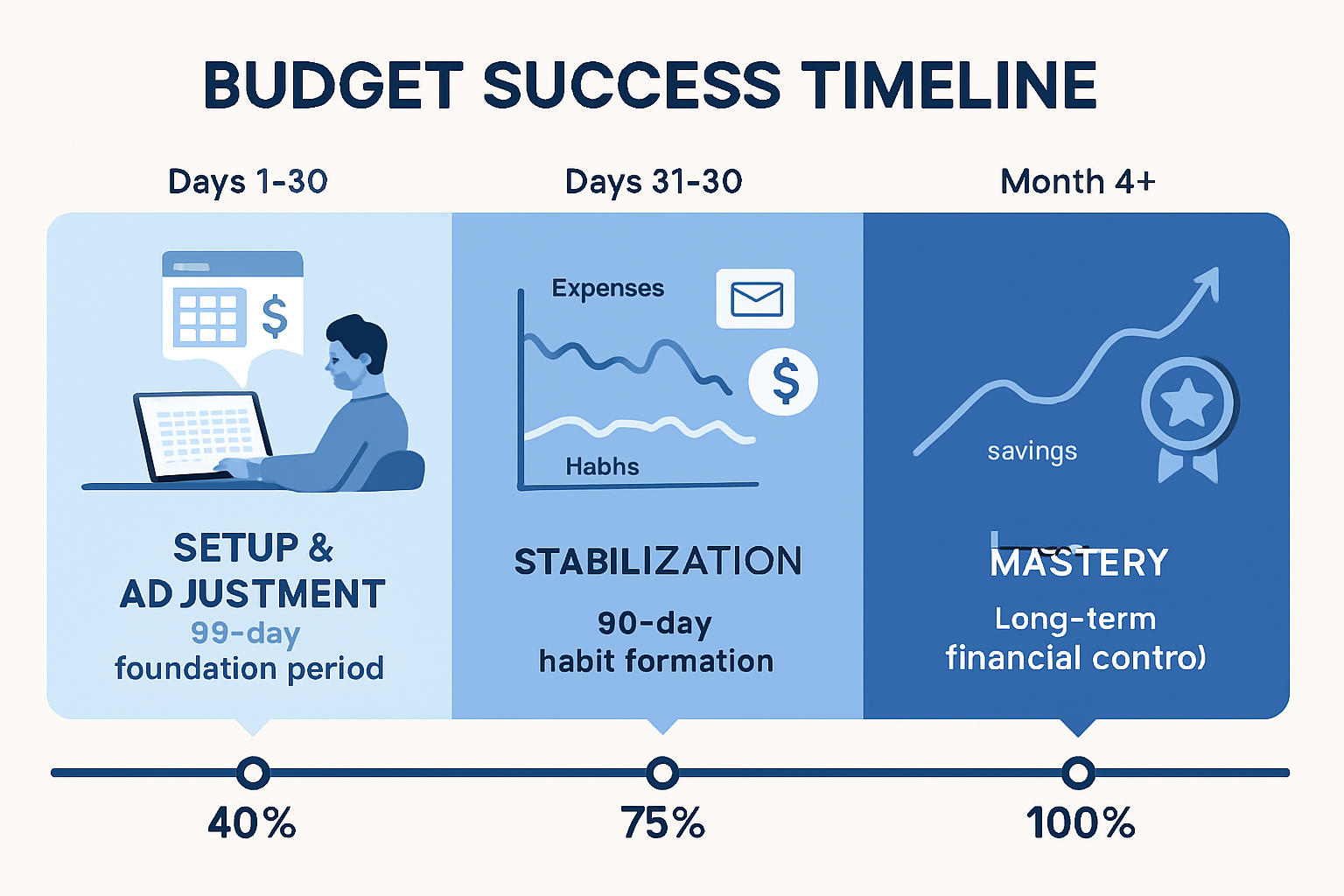

The first 90 days establish the habit, expect adjustment periods rather than immediate perfection

What Does It Mean to Create a Budget That Works?

A budget that works means your financial system produces consistent results: bills get paid on time, savings grow automatically, and spending aligns with stated priorities without constant manual intervention.

The “working” qualifier matters. Most budgets fail within 30 days because they prioritize theoretical perfection over practical sustainability. A perfect budget that you abandon after two weeks produces zero value. A simple budget that you maintain for two years builds measurable wealth.

The math behind effective budgeting centers on three principles:

- Income allocation beats expense restriction: Assigning every dollar a specific job before spending occurs creates intentionality without deprivation

- Automation compounds consistency: Systems that run without daily decisions produce better long-term results than willpower-dependent approaches

- Buffer categories absorb reality: Life includes irregular expenses and miscellaneous purchases—budgets that ignore this fail predictably

Why Most Budgets Fail

Traditional budgeting advice creates three common failure points:

Unrealistic category limits that ignore actual spending patterns lead to immediate discouragement. Telling someone who spends $800 monthly on groceries to “just cut it to $400” without addressing buying habits, family size, or dietary needs guarantees failure.

No buffer for irregular expenses means car repairs, annual subscriptions, or holiday spending destroy the budget every time. These aren’t emergencies—they’re predictable irregular expenses that require dedicated sinking funds.

Manual tracking requirements create unsustainable friction. Budgets that demand recording every $3 coffee purchase require more time than most people can consistently allocate, leading to abandonment.

A working budget acknowledges these realities and builds systems around human behavior rather than fighting it. This approach aligns with behavioral finance principles that recognize decision fatigue and cognitive limitations.

Step 1 – Calculate Your Monthly Income (The Right Way)

Accurate income calculation forms the foundation of every budget decision. Overestimating creates deficit spending; underestimating leaves money unallocated and vulnerable to lifestyle inflation.

Start with net income, not gross. Your budget operates on actual take-home pay after taxes, retirement contributions, and other deductions. A $60,000 salary translates to approximately $3,750 monthly after federal taxes, state taxes, FICA, and standard deductions, not the $5,000 gross calculation suggests.

Fixed Income vs Variable Income

Fixed income earners (salaried employees with consistent paychecks) calculate monthly income by reviewing the last three pay stubs and averaging the net amounts. Account for:

- Base salary after all deductions

- Consistent overtime or shift differentials

- Automatic retirement contributions (these reduce available income)

- Regular commission or bonus payments with a 12+ month history

Variable income earners (freelancers, commission-based sales, and hourly workers with fluctuating schedules) face greater complexity. Income volatility requires conservative estimation to prevent overspending during lean months.

How to Budget with Irregular Income

The lowest-month method provides the most sustainable approach for irregular income:

- Review the past 12 months of income statements

- Identify the three lowest-earning months

- Calculate the average of those three months

- Use this figure as your baseline monthly budget

Example calculation:

- Lowest three months: $2,800, $3,100, $2,900

- Average: ($2,800 + $3,100 + $2,900) ÷ 3 = $2,933

- Budget baseline: $2,933 monthly

This conservative approach ensures your budget functions during slow periods. Higher-earning months create an automatic surplus for savings, debt repayment, or irregular expense funds rather than inflating your lifestyle.

For those managing variable income alongside active income strategies, this baseline method prevents the feast-or-famine cycle that derails financial progress.

Quarterly income adjustments refine accuracy. Every three months, recalculate the lowest-month average to account for business growth, seasonal patterns, or market changes. This creates a responsive system that adapts to reality without constant revision.

Step 2 – Track Your Expenses (Without Overthinking)

Expense tracking reveals where money actually goes versus where you think it goes—the gap often exceeds 30% of income.

The two-week baseline method provides clarity without overwhelming detail:

- Track every expense for 14 consecutive days

- Categorize spending into 8-10 major groups

- Multiply two-week totals by 2.17 to estimate monthly spending

- Compare results to actual bank statements for accuracy

This short-term intensive tracking builds awareness without creating permanent tracking fatigue. Most spending patterns emerge clearly within two weeks, revealing priorities and problem areas.

Fixed vs Variable Expenses Explained

Fixed expenses remain constant month-to-month and include:

- Rent or mortgage payments

- Car payments and insurance

- Subscription services (streaming, software, memberships)

- Minimum debt payments

- Phone and internet bills

These expenses total to a consistent baseline that rarely changes without deliberate decisions. Fixed expenses typically represent 50-60% of total spending for most households.

Variable expenses fluctuate based on usage and decisions:

- Groceries and dining out

- Utilities (electricity, water, gas)

- Gasoline and transportation

- Entertainment and recreation

- Clothing and personal care

Variable expenses create budgeting challenges because they respond to both intentional choices and external factors (weather affecting utility bills, gas price changes, seasonal needs).

Needs vs Wants Breakdown

The needs-versus-wants distinction determines allocation priorities, though the boundary isn’t always obvious.

True needs support for basic survival and earning capacity:

- Housing (rent/mortgage, utilities, basic maintenance)

- Food (groceries for home cooking, not restaurant meals)

- Transportation to work

- Essential clothing

- Minimum insurance coverage

- Required debt payments

Wants to enhance quality of life, but aren’t survival-essential:

- Dining out and takeout meals

- Entertainment subscriptions beyond one or two services

- New clothing beyond replacing worn items

- Upgraded housing beyond basic shelter

- Vehicle upgrades beyond reliable transportation

The gray area includes items like smartphones (essential for modern employment, but luxury models represent wants) and internet service (increasingly essential for work, but premium speeds may be wants).

Apply the substitution test: If a cheaper alternative exists that meets the core need, the premium version represents a want. Basic transportation is a need; a new luxury vehicle is a want. Internet access is a need; gigabit fiber is likely a want.

Understanding this distinction enables intelligent allocation using frameworks like the 50/30/20 budgeting rule, which explicitly separates needs (50%), wants (30%), and savings (20%).

Step 3 – Choose a Budgeting Method That Fits Your Life

No single budgeting system works for everyone. Income patterns, personality types, and financial goals require different approaches.

The math behind successful budgeting shows that method adherence matters more than method selection, a simple system you maintain beats a complex system you abandon.

The 50/30/20 Budget

The 50/30/20 framework divides after-tax income into three categories:

- 50% for needs: Housing, utilities, groceries, transportation, insurance, minimum debt payments

- 30% for wants: Dining out, entertainment, hobbies, subscriptions, non-essential purchases

- 20% for savings and extra debt payments: Emergency fund, retirement contributions, additional principal payments

Example for $4,000 monthly net income:

| Category | Percentage | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Needs | 50% | $2,000 |

| Wants | 30% | $1,200 |

| Savings/Debt | 20% | $800 |

This method works best for:

- Beginners who need simple guidelines

- People with a relatively stable income

- Those who dislike detailed tracking

- Individuals starting from zero savings

Limitations: The 50/30/20 split assumes moderate housing costs. In high cost-of-living areas where rent exceeds 50% of income alone, this framework requires adjustment to 60/20/20 or 70/15/15 temporarily while working toward housing cost optimization.

Zero-Based Budgeting

Zero-based budgeting assigns every dollar a specific job until income minus all allocations equals exactly zero.

The formula: Income – (All Expenses + Savings + Debt Payments) = $0

This doesn’t mean spending everything; savings and investments count as “expenses” in the allocation. The goal is intentional assignment rather than letting money sit unallocated in checking accounts.

Example for $5,000 monthly income:

Income: $5,000

Fixed Expenses:

- Rent: $1,400

- Car payment: $350

- Insurance: $200

- Utilities: $150

- Phone: $80

Variable Expenses:

- Groceries: $500

- Gas: $200

- Dining out: $300

- Entertainment: $150

Savings & Debt:

- Emergency fund: $500

- Retirement (IRA): $500

- Extra credit card payment: $400

- Sinking funds: $270

Total allocated: $5,000

Remaining: $0Zero-based budgeting works best for:

- Detail-oriented individuals who enjoy planning

- People recovering from overspending patterns

- Those with specific debt payoff goals

- Households with complex expense structures

The primary advantage: This method eliminates “leftover money” that disappears into untracked spending. Every dollar has a predetermined purpose before the month begins.

Pay-Yourself-First Method

The pay-yourself-first approach prioritizes savings and investments by allocating them before discretionary spending occurs.

The sequence:

- Income arrives

- Automated transfers immediately move savings percentages to dedicated accounts

- Fixed expenses get paid

- Remaining funds cover variable expenses and wants

This method leverages behavioral finance principles: money you never see in your checking account doesn’t trigger spending temptation.

Implementation example for $4,500 monthly income:

- Immediate automated transfers (day after payday):

- Emergency fund: $450 (10%)

- Retirement account: $675 (15%)

- Sinking funds: $225 (5%)

- Total saved: $1,350 (30%)

- Remaining for expenses: $3,150

- Fixed expenses: $2,100

- Variable expenses: $1,050

This approach works best for:

- People who struggle with impulse spending

- Those building emergency funds from zero

- Individuals focused on wealth building through compound growth

- Anyone who prefers automation over manual decisions

Critical success factor: Set up automatic transfers for the day after payday. Waiting until “later in the month” defeats the purpose and allows spending to consume savings capacity.

Envelope System (Cash & Digital)

The envelope system allocates cash to physical envelopes labeled by category. When an envelope empties, spending in that category stops until next month.

Traditional cash envelope method:

- Withdraw monthly budgeted amounts in cash

- Divide cash into labeled envelopes (groceries, gas, entertainment, etc.)

- Use only envelope cash for each category

- When empty, stop spending in that category

Digital envelope alternatives include:

- Multiple checking accounts (one per major category)

- Budgeting apps with virtual envelope features (YNAB, Goodbudget, Mvelopes)

- Separate debit cards for different spending categories

The envelope system works best for:

- Visual learners who need tangible spending limits

- People recovering from credit card debt

- Those who overspend with digital payments

- Individuals who need immediate spending feedback

Modern hybrid approach: Use cash envelopes for problem categories (dining out, entertainment, personal spending) while keeping fixed expenses (rent, utilities, insurance) on automated digital payments. This combines the psychological benefit of physical limits with the convenience of automation for predictable bills.

Step 4 – Set Realistic Spending Limits

Unrealistic spending limits guarantee budget failure. The math behind sustainable budgeting requires category allocations based on actual spending patterns rather than aspirational goals.

Start with reality, then optimize. If you currently spend $800 monthly on groceries, a budget that allocates $400 without changing shopping habits, family size, or dietary needs will fail within weeks. Instead:

- Begin with current spending levels

- Identify one category for a 10-15% reduction

- Implement specific behavior changes to achieve the reduction

- Maintain for 60 days before attempting additional cuts

This incremental approach produces sustainable results because it allows habit formation between changes.

How to Avoid “Budget Burnout”

Budget burnout occurs when restriction fatigue overwhelms motivation, leading to complete abandonment of the system.

Prevention strategies:

Build in discretionary spending: Allocate 5-10% of income to “no-questions-asked” personal spending. This category requires zero justification and absorbs impulse purchases without guilt. The psychological relief of unrestricted spending money prevents rebellion against the entire budget.

Create realistic timelines: Aggressive debt payoff goals or extreme savings rates often backfire. A moderate approach sustained for three years outperforms an extreme approach abandoned after three months. Calculate sustainable rates using the formula:

Maximum sustainable savings rate = (Current savings rate) + 5% per quarter

Schedule planned splurges: Budget for quarterly “fun money” allocations ($200-500 depending on income) for guilt-free enjoyment. Knowing a planned splurge exists in three months reduces the psychological pressure that leads to impulsive budget violations.

Avoid comparison traps: Personal finance social media often showcases extreme frugality or aggressive savings rates that aren’t sustainable for most people. Your budget serves your life circumstances, not internet validation.

Building Buffer Categories

Buffer categories absorb irregular expenses and miscellaneous spending that derail rigid budgets.

Miscellaneous fund (5% of income): This catch-all category covers:

- Unplanned but necessary purchases

- Gifts for unexpected occasions

- Small household items

- Minor car maintenance

- Forgotten subscriptions or fees

A $4,000 monthly income should include a $200 miscellaneous buffer. This prevents the “$47 Target run” from becoming a budget crisis.

Sinking funds are dedicated savings accounts for predictable irregular expenses:

| Expense Category | Annual Cost | Monthly Allocation |

|---|---|---|

| Car insurance (6-month policy) | $1,200 | $100 |

| Holiday gifts | $800 | $67 |

| Car maintenance | $600 | $50 |

| Annual subscriptions | $300 | $25 |

| Home repairs | $1,200 | $100 |

| Total | $4,100 | $342 |

These expenses aren’t emergencies—they’re predictable costs that occur irregularly. Allocating monthly amounts prevents the “surprise” $600 car insurance bill from derailing your budget or forcing credit card debt.

Implementation: Open a high-yield savings account and set up automatic monthly transfers for the total sinking fund amount. Track individual category balances using a simple spreadsheet or budgeting app. When the expense occurs, transfer money from savings to checking and pay the bill without budget disruption.

This approach aligns with cash flow management principles that smooth irregular expenses across time periods.

Step 5 – Automate Your Budget (So It Runs Itself)

Automation eliminates 80% of budgeting friction by removing repetitive manual decisions. The result: better consistency, fewer missed payments, and reduced cognitive load.

The automation hierarchy:

- Savings and investments (highest priority)

- Fixed recurring expenses (rent, insurance, subscriptions)

- Variable recurring expenses (utilities, phone)

- Debt payments beyond minimums

This sequence ensures wealth-building activities occur before consumption spending can interfere.

Automating Bills

Modern banking and billing systems enable complete automation for most fixed expenses:

Set up automatic payments for:

- Rent or mortgage (through bank bill pay or landlord portal)

- Insurance premiums (auto, health, life, renters)

- Subscription services (streaming, software, memberships)

- Loan payments (student loans, car payments, personal loans)

- Utilities (electricity, gas, water, internet, phone)

Timing strategy: Schedule all automatic payments for 2-3 days after payday. This ensures funds are available and creates a consistent payment rhythm.

Safety protocols:

- Maintain a buffer of 1-2 weeks’ expenses in checking to prevent overdrafts

- Review automated payments quarterly to catch price increases or forgotten subscriptions

- Set up low-balance alerts ($500 threshold) to catch potential issues

- Keep a master list of all automated payments with amounts and dates

The forgotten subscription problem: Americans waste an average of $273 monthly on unused subscriptions.[3] Quarterly reviews identify and eliminate these silent budget drains. For guidance on managing recurring payments, review autopay best practices.

Automating Savings

Automated savings removes willpower from the equation. Money transferred before you see it in your checking account doesn’t trigger spending temptation.

Implement a multi-account savings structure:

- Emergency fund account (high-yield savings)

- Automatic transfer: 10% of each paycheck

- Goal: 3-6 months of expenses

- Access: Same bank for easy emergency access

- Sinking funds account (high-yield savings)

- Automatic transfer: Calculated monthly amount for irregular expenses

- Goal: Fully funded irregular expense categories

- Access: Same bank, separate from emergency fund

- Retirement accounts (401k, IRA)

- Automatic deduction: 10-15% of gross income

- Goal: Maximum employer match minimum, 15% optimal

- Access: Restricted until retirement (prevents impulse withdrawal)

- Investment accounts (brokerage, index funds)

- Automatic transfer: After the emergency fund reaches 3 months

- Goal: Long-term wealth building

- Access: Available but designated for growth

Bi-weekly paychecks create a bonus opportunity: If paid bi-weekly, you receive 26 paychecks annually (2.17 per month). Budget based on two paychecks monthly, then treat the two “extra” paychecks as automatic savings or debt payoff bonuses.

For those exploring compound interest accounts, automation ensures consistent contributions that maximize growth over time.

Best Budgeting Apps vs Spreadsheets

The optimal budgeting tool balances functionality with sustainability—the best system is the one you’ll actually use.

Budgeting apps:

Advantages:

- Automatic transaction import and categorization

- Real-time spending tracking

- Mobile access for on-the-go updates

- Visual dashboards and progress tracking

- Automated alerts for overspending

Popular options:

- YNAB (You Need A Budget): Zero-based budgeting framework, $99/year, steep learning curve, but powerful for detail-oriented users

- Mint: Free, automatic categorization, good for passive tracking, limited customization

- PocketGuard: Simplified “in my pocket” view, good for overspenders, $7.99/month premium

- Goodbudget: Digital envelope system, free for 10 envelopes, $8/month for unlimited

Spreadsheets:

Advantages:

- Complete customization control

- No subscription costs

- Privacy (no account linking required)

- Unlimited complexity for detailed tracking

- Works offline

Disadvantages:

- Manual data entry required

- No automatic transaction import

- Requires spreadsheet knowledge for setup

- No mobile-optimized interface

- Easier to abandon due to manual friction

The hybrid approach combines app automation with spreadsheet analysis:

- Use an app for daily transaction tracking and categorization

- Export monthly data to a spreadsheet for deeper analysis

- Create custom spreadsheet dashboards for long-term trends

- Maintain manual control over strategic planning

Decision framework:

- Choose apps if you value convenience and real-time tracking

- Choose spreadsheets if you prefer privacy and customization

- Choose a hybrid if you want both automation and analytical depth

For additional budgeting context, the complete budget guide provides framework comparisons and implementation strategies.

Step 6 – Review and Adjust Weekly (The Missing Step)

Most budgeting advice recommends monthly reviews, but this creates a 30-day blind spot where small problems compound into major issues.

Weekly reviews prevent monthly disasters. A 10-minute weekly check-in catches overspending early enough to adjust behavior before the category depletes completely.

Weekly Money Check-Ins

The 10-minute weekly review process:

1. Review spending against budget (5 minutes):

- Check each category’s spending vs. allocation

- Identify categories approaching limits

- Note any unusual transactions

- Verify all automated payments processed correctly

2. Adjust upcoming spending (3 minutes):

- Reduce discretionary spending in overspent categories

- Reallocate from underspent categories if needed

- Plan for upcoming irregular expenses

- Confirm sufficient funds for scheduled payments

3. Update tracking system (2 minutes):

- Categorize any uncategorized transactions

- Reconcile credit card spending against the budget

- Update sinking fund balances

- Note lessons learned or behavior patterns

Optimal timing: Sunday evening or Monday morning provides a weekly reset point and allows planning for the week ahead.

The compound benefit: Weekly reviews create a feedback loop that improves spending awareness. Research shows that people who review finances weekly spend 15-20% less in discretionary categories compared to those who review monthly.

Monthly Budget Reset System

The monthly reset process takes 30-45 minutes and serves three purposes: reconciliation, adjustment, and planning.

Monthly reset checklist:

Week 4 of the current month:

- Calculate actual spending in each category

- Compare actual vs budgeted amounts

- Identify patterns (consistent overages, consistent savings)

- Review irregular expenses for next month

- Adjust category allocations based on data

- Set up next month’s budget with refined numbers

Example adjustment process:

| Category | Budgeted | Actual | Variance | Next Month |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groceries | $600 | $720 | +$120 | $650 |

| Dining Out | $300 | $180 | -$120 | $250 |

| Gas | $200 | $240 | +$40 | $220 |

| Entertainment | $150 | $150 | $0 | $150 |

This data-driven approach eliminates guesswork. If you consistently spend $720 on groceries, budgeting $600 creates artificial failure. Adjust the budget to reflect reality, then implement specific strategies to reduce spending if desired.

The 90-day optimization cycle: After three months of data, patterns emerge clearly. Some categories stabilize while others require permanent adjustment. This evidence-based refinement creates a budget that matches your actual life rather than theoretical ideals.

Common Budgeting Mistakes (And How to Fix Them)

Understanding failure patterns prevents repeating them. These five mistakes account for 80% of budget abandonments.

Mistake 1: Unrealistic Category Allocations

The problem: Setting grocery budgets at $300 when actual spending is $700, or allocating $50 for entertainment when typical spending is $250.

The fix: Start with three months of actual spending data. Set initial budget categories at 90% of average spending, then reduce by 5-10% monthly if optimization is desired. This gradual approach allows behavior change without shock.

Mistake 2: Forgetting Irregular Expenses

The problem: Budgeting only for monthly recurring expenses while ignoring quarterly insurance premiums, annual subscriptions, holiday spending, and car maintenance.

The fix: Create a comprehensive irregular expense list:

- Review the past 12 months of bank and credit card statements

- Identify all non-monthly expenses

- Calculate annual total

- Divide by 12 for monthly sinking fund allocation

- Automate monthly transfers to dedicated savings

Common irregular expenses checklist:

- Car insurance (if paid semi-annually)

- Car registration and taxes

- Home/renters insurance (if paid annually)

- HOA fees (if paid quarterly or annually)

- Amazon Prime and other annual subscriptions

- Holiday and birthday gifts

- Back-to-school expenses

- Veterinary care

- Professional dues or licenses

- Tax preparation fees

Mistake 3: No Fun Money

The problem: Allocating 100% of income to needs, debt, and savings with zero discretionary spending allowance.

The fix: Budget 5-10% of income for “no-questions-asked” personal spending. This category prevents the deprivation mindset that leads to budget rebellion. A $4,000 monthly income should include $200-400 for guilt-free spending on whatever brings joy.

The psychology: Complete restriction triggers psychological reactance—the impulse to rebel against imposed limits. Small amounts of unrestricted spending satisfy this need without derailing financial progress.

Mistake 4: Tracking Everything Manually

The problem: Attempting to record every transaction in real-time creates unsustainable friction that leads to abandonment.

The fix: Automate transaction tracking through bank account linking and app categorization. Reserve manual tracking for cash purchases only. Focus weekly reviews on category totals rather than individual transactions.

The 80/20 rule: Tracking the top 5-7 spending categories captures 80% of total spending. Obsessing over every $2 purchase provides minimal value while consuming significant time.

Mistake 5: Giving Up After One Bad Month

The problem: Viewing a single month of overspending as a complete failure and abandoning the budget entirely.

The fix: Expect imperfection, especially during the first 90 days. Budget success measures improvement over time, not monthly perfection. A month where you overspent by $200 beats the previous pattern of not tracking at all.

The recovery protocol:

- Identify what caused the overspending (unexpected expense, behavioral slip, unrealistic allocation)

- Adjust the budget to prevent recurrence

- Reset for the new month without guilt

- Continue the weekly review process

Long-term perspective: Building a sustainable budget takes 3-6 months of consistent effort. Early struggles represent learning, not failure. For additional context on managing financial setbacks, explore cash flow management strategies.

Example: A Simple Budget That Actually Works

Real-world examples clarify abstract concepts. This sample budget demonstrates practical allocation for a $3,500 monthly net income using the 50/30/20 framework with modifications.

Sample Monthly Budget Breakdown

Household: Single person, renting, moderate cost-of-living area

| Category | Amount | % of Income | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| INCOME | $3,500 | 100% | After-tax take-home |

| NEEDS (52%) | $1,820 | ||

| Rent | $950 | 27% | Includes water/trash |

| Utilities | $120 | 3% | Electric, gas |

| Groceries | $350 | 10% | Home cooking focus |

| Transportation | $200 | 6% | Gas, maintenance fund |

| Car insurance | $85 | 2% | Paid monthly |

| Renters insurance | $15 | 0.4% | Paid monthly |

| Phone | $50 | 1.4% | Prepaid plan |

| Minimum debt payment | $50 | 1.4% | Credit card minimum |

| WANTS (28%) | $980 | ||

| Dining out | $200 | 6% | Restaurants, takeout |

| Entertainment | $100 | 3% | Movies, events, hobbies |

| Subscriptions | $45 | 1.3% | Streaming, apps |

| Personal care | $80 | 2% | Haircuts, toiletries |

| Clothing | $75 | 2% | Averaged monthly |

| Gym membership | $40 | 1% | Health investment |

| Fun money | $175 | 5% | No-questions spending |

| Miscellaneous buffer | $175 | 5% | Unexpected wants |

| Gifts | $90 | 2.6% | Birthdays, occasions |

| SAVINGS & DEBT (20%) | $700 | ||

| Emergency fund | $250 | 7% | Building to $10,000 |

| Sinking funds | $150 | 4% | Irregular expenses |

| Retirement (Roth IRA) | $200 | 6% | Long-term investing |

| Extra debt payment | $100 | 3% | Credit card principal |

| TOTAL ALLOCATED | $3,500 | 100% | Zero-based allocation |

Why This Budget Works

1. Realistic category amounts: Each allocation reflects typical spending patterns rather than aspirational goals. The $350 grocery budget accommodates actual food costs for one person without requiring extreme couponing.

2. Built-in flexibility: The $175 miscellaneous buffer and $175 fun money (10% combined) absorb unexpected purchases and impulse spending without derailing the plan.

3. Multiple savings goals: Rather than a single “savings” category, this budget separates emergency funds, sinking funds, retirement, and debt payoff, each serving a distinct purpose.

4. Balanced priorities: At 52% for needs, this budget slightly exceeds the standard 50% recommendation due to realistic housing costs, while maintaining a strong 20% savings/debt allocation.

5. Automation-ready: Every category can be automated (savings transfers, fixed bills) or easily tracked (variable expenses, discretionary spending).

Modification for different incomes:

- $2,500 income: Reduce wants to 20%, increase needs to 60%, maintain 20% savings minimum

- $5,000 income: Maintain needs around 45%, increase savings to 25-30%, allow wants to reach 30%

- $7,000+ income: Keep needs under 40%, push savings to 30-40%, limit lifestyle inflation in wants

The percentages matter less than the principles: cover true needs, allocate intentionally for wants, and prioritize wealth-building through consistent savings.

For those managing transportation costs, the 20/4/10 rule for car buying provides additional guidance on sustainable vehicle budgeting.

How Long Does It Take for a Budget to Work?

Budget success unfolds in three distinct phases, each with different expectations and challenges.

Phase 1: The First 30 Days (Foundation Period)

What happens:

- Initial setup and category creation

- First round of tracking and awareness building

- Inevitable overspending in some categories

- Discovery of forgotten expenses and subscriptions

- Learning curve with the chosen budgeting method

Expected outcomes:

- 60-70% accuracy in category predictions

- Identification of major spending patterns

- 2-3 budget violations or adjustments

- Increased spending awareness even without perfect adherence

Success metric: Completing the full month without abandoning the system, regardless of perfect execution.

The psychological shift: Most people experience surprise at actual spending levels. The average person underestimates discretionary spending by 25-40% before tracking begins.[5]

Phase 2: Days 31-90 (Stabilization Period)

What happens:

- Category allocations refined based on actual data

- Automation systems are fully implemented

- Behavioral patterns become clearer

- Sinking funds begin accumulating

- Emergency fund shows measurable growth

Expected outcomes:

- 80-85% accuracy in budget predictions

- Reduced overspending incidents

- Stronger habit formation around weekly reviews

- Increased confidence in financial control

Success metric: Three consecutive months of tracking with improved accuracy and reduced stress around money decisions.

The habit formation window: Research indicates that financial habits solidify between 60-90 days of consistent practice. This period determines long-term sustainability.

Phase 3: Month 4+ (Mastery Period)

What happens:

- Budget becomes semi-automatic through established routines

- Category allocations stabilize with minimal monthly changes

- Savings accounts show compound growth

- Debt balances decrease measurably

- Financial confidence increases significantly

Expected outcomes:

- 90%+ accuracy in budget predictions

- Rare overspending incidents with quick recovery

- Automated systems handling 80% of budget execution

- Visible progress toward financial goals

Success metric: Budget maintenance requires less than 30 minutes weekly, with financial stress significantly reduced compared to the pre-budget baseline.

The compound effect: After six months of consistent budgeting, most people report:

- 15-25% reduction in discretionary spending

- 3-6 times increase in monthly savings

- Elimination of overdraft fees and late payments

- Measurable progress toward major financial goals

Understanding compound growth principles reveals how small monthly improvements create significant long-term wealth differences.

When a Budget Still Doesn’t Work (What to Do Next)

Sometimes, consistent budgeting effort fails to produce results. This indicates a structural problem requiring different solutions.

Income Problem vs Spending Problem

Diagnostic question: After cutting all discretionary spending, can you cover basic needs (housing, food, utilities, transportation, minimum debt payments)?

If YES: You have a spending problem, behavior changes, and category optimization will solve it.

If NO: You have an income problem; earning more takes priority over cutting further.

The math test:

Minimum survival expenses = Rent + Utilities + Basic groceries + Transportation + Minimum debt payments

If minimum survival > 80% of income → Income problem

If minimum survival < 80% of income → Spending problemSolving Spending Problems

When income sufficiently covers needs, but money still disappears:

1. Implement the cash diet:

- Withdraw weekly spending allowance in cash

- Use cash only for discretionary categories

- When cash depletes, stop spending

- Duration: 30-60 days to reset spending psychology

2. Apply the 24-hour rule:

- Wait 24 hours before any non-essential purchase over $50

- Wait 7 days for purchases over $200

- Wait 30 days for purchases over $500

- This delay reduces impulse purchases by 60-70%

3. Eliminate spending triggers:

- Unsubscribe from retail email lists

- Delete shopping apps from your phone

- Avoid stores during vulnerable times (hungry, stressed, bored)

- Use browser extensions that block deal sites

4. Increase friction for spending:

- Remove saved payment information from websites

- Freeze credit cards (literally, in ice)

- Require manual entry of card numbers for each purchase

- Use separate accounts for bills vs. discretionary spending

Solving Income Problems

When legitimate needs exceed income despite reasonable spending:

Immediate actions:

- Apply for assistance programs: SNAP (food assistance), LIHEAP (utility assistance), Medicaid (healthcare), and housing assistance

- Negotiate bills: Call providers for lower rates, payment plans, or hardship programs

- Eliminate non-essential subscriptions: Even $10-20 monthly reductions help

- Sell unused items: Generate one-time cash for immediate needs

Short-term income increases:

- Overtime or extra shifts at current job

- Gig economy work: Rideshare, delivery, task services

- Freelance services: Writing, design, virtual assistance

- Part-time employment: Evenings or weekends

Long-term income solutions:

- Skill development: Certifications, training for higher-paying roles

- Career advancement: Promotions, job changes, industry switches

- Side business development: Scalable income beyond hourly work

- Education investment: Degrees or credentials with clear ROI

The priority equation:

If (Current income - Survival needs) < $500 monthly

Then: Income increase > Spending reduction

Else: Optimize both simultaneouslyFor those managing tight budgets, strategies for saving money on low income provide additional practical approaches.

When professional help makes sense:

- Debt exceeds 50% of annual income

- Consistent inability to meet minimum payments

- Considering bankruptcy

- Chronic overspending despite tracking efforts

- Mental health issues affecting financial decisions

Credit counseling agencies (NFCC-certified), financial therapists, and fee-only financial planners provide objective guidance when self-directed efforts plateau.

💰 Personal Budget Calculator

Calculate your ideal budget allocation in seconds

Conclusion

Learning how to create a budget that actually works requires understanding a fundamental truth: sustainable budgets serve your life rather than restricting it.

The math behind effective budgeting reveals clear cause-and-effect relationships. When income flows into predetermined categories based on actual priorities and spending patterns, financial stress decreases while savings increase automatically. This isn’t a restriction—it’s an intentional allocation that transforms money from a source of anxiety into a tool for achieving specific goals.

The key principles that separate working budgets from abandoned ones:

- Start with reality, not aspiration: Base category allocations on actual spending data, then optimize gradually rather than imposing unrealistic restrictions that guarantee failure

- Choose methods that match your life: The 50/30/20 rule, zero-based budgeting, pay-yourself-first, and envelope systems each solve different problems—select based on income pattern and personality

- Automate relentlessly: Systems that run without daily decisions produce better long-term results than willpower-dependent approaches

- Build in buffers: Miscellaneous funds and sinking funds absorb irregular expenses that derail rigid budgets

- Review weekly, adjust monthly: Small course corrections prevent major disasters and create feedback loops that improve spending awareness

Your next steps:

Week 1: Calculate accurate monthly net income and track all expenses for 14 consecutive days to establish baseline spending patterns.

Week 2: Choose one budgeting method (start with 50/30/20 if uncertain) and create initial category allocations based on tracking data.

Week 3: Set up automation for savings transfers and fixed bills, then implement your first weekly review process.

Week 4: Complete your first monthly reset, adjust categories based on actual results, and plan for month two with refined allocations.

The first 90 days determine long-term success. Expect imperfection, adjust based on data rather than emotion, and measure progress in months rather than days. A budget that you maintain with 80% accuracy for three years builds significantly more wealth than a perfect budget abandoned after three weeks.

Remember: Budgeting isn’t about achieving perfection—it’s about creating a sustainable system that allocates money intentionally, builds wealth consistently, and reduces financial stress permanently. The math works when the system works, and the system works when it matches your actual life.

Start today. Track for two weeks. Choose a method. Automate what you can. Review weekly. Adjust monthly. The compound effect of these simple actions creates a financial transformation that extends far beyond monthly budgets into long-term wealth building and financial security.

For those ready to expand beyond budgeting basics, explore dividend investing strategies and compound interest principles to understand how consistent savings grow into substantial wealth over time.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial advice. Budgeting strategies, allocation percentages, and financial recommendations presented here represent general guidelines that may not suit every individual’s unique circumstances.

Financial decisions carry risk. Before implementing any budgeting method or making significant financial changes, consider consulting with a qualified financial advisor, certified financial planner, or licensed professional who can evaluate your specific situation, goals, and constraints.

Individual results vary. The timelines, percentages, and outcomes described in this article represent typical scenarios based on research and common patterns. Your personal results may differ significantly based on income level, geographic location, family size, existing debt, health circumstances, and numerous other factors.

No guarantees. While the budgeting methods and strategies outlined here have proven effective for many individuals, no financial approach guarantees specific results. Economic conditions, personal circumstances, and external factors beyond your control can impact financial outcomes.

Accuracy limitations. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented, financial regulations, tax laws, and best practices evolve over time. Verify current information with authoritative sources before making decisions.

The Rich Guy Math and Max Fonji assume no responsibility or liability for any decisions made based on the information provided in this article. You assume full responsibility for your financial decisions and their consequences.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that explains the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and risk management. With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based education, Max translates complex financial concepts into actionable strategies for beginners and intermediate investors.

Max’s approach combines analytical precision with practical application, helping readers understand not just what to do with money, but why specific strategies work based on mathematical principles and empirical evidence. His work focuses on demystifying compound interest, valuation methods, budgeting frameworks, and investment fundamentals through clear explanations and real-world examples.

Through The Rich Guy Math, Max provides educational content that empowers readers to make informed financial decisions based on logic, data, and proven principles rather than emotional reactions or marketing hype.

References

[1] Federal Reserve. (2024). “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/

[2] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2023). “Financial Well-Being in America.” CFPB Research Report. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/

[3] West Monroe Partners. (2024). “Subscription Service Study: Consumer Spending Patterns.” Financial Services Research. https://www.westmonroe.com/

[4] Journal of Consumer Research. (2023). “The Impact of Financial Monitoring Frequency on Spending Behavior.” Oxford Academic Press.

[5] American Psychological Association. (2024). “Stress in America: Money and Financial Decision-Making.” APA Center for Organizational Excellence. https://www.apa.org/

FAQ: How to Create a Budget

How do I create a budget if I live paycheck to paycheck?

Start by tracking every expense for one week to identify spending patterns and leaks. Use the pay-yourself-first method to automatically save even $25 per paycheck before other expenses.

Focus on building a small buffer fund of $500–$1,000 first, then optimize spending categories. If your income varies, use the lowest-month income method. Eliminating just one discretionary expense can create immediate breathing room.

What’s the easiest budget method for beginners?

The 50/30/20 rule is one of the simplest budgeting methods. Allocate 50% of after-tax income to needs, 30% to wants, and 20% to savings and debt repayment.

This approach requires minimal tracking and provides clear targets. Automate the 20% savings portion first, then manage the remaining income without micromanaging every transaction.

How often should I update my budget?

Review your budget weekly for 10–15 minutes to catch issues early. Perform a full monthly reset to reconcile actual spending with budgeted amounts and plan for the next month.

Update income immediately when pay changes, and reassess categories quarterly as life circumstances evolve. This layered review system prevents small problems from becoming major financial setbacks.

Can a budget work without tracking every expense?

Yes. Focus on the three largest categories—housing, transportation, and food—which typically account for 60–70% of spending.

Automate fixed expenses and savings, then use a simplified framework like the 50/30/20 rule for discretionary spending. A miscellaneous buffer category (5–10% of income) absorbs small purchases without derailing the budget.

What if my income changes every month?

Use the lowest-month method by calculating the average of your three lowest-earning months from the past year and building your budget around that number.

When higher-income months occur, direct the surplus toward savings, debt repayment, or irregular expense funds. This approach stabilizes spending during lean months and creates automatic progress during strong months.

Is budgeting still useful if I use credit cards?

Absolutely. Credit cards are payment tools, not spending categories. Budget for the expense itself, then ensure your credit card payment category covers the full statement balance each month.

Track credit card spending against your budget in real time to avoid “invisible spending.” Paying the balance in full preserves cash flow control and supports healthy credit utilization.