Credit cycling is the practice of paying down a credit card balance during the billing cycle and then reusing the available credit before the statement closes, often multiple times in the same month. Cardholders use credit cycling to effectively spend more than their stated credit limit, usually to manage cash flow, earn rewards, or cover large expenses. While credit cycling is legal, it can raise red flags with credit card issuers and may lead to account reviews, spending limits, or even shutdowns if misused.

Credit cycling is a tactic built around how lenders evaluate borrower behavior inside the credit system.

This guide breaks down exactly what credit cycling is, how it works, when it might make sense, and, most importantly, the risks every beginner must understand before attempting it. Because in the world of credit scores and financial literacy, understanding cause and effect isn’t optional; it’s essential.

Key Takeaways

- Credit cycling means making multiple payments within one billing cycle to spend more than your credit limit allows, resetting your available credit repeatedly.

- Utilization matters more: Your credit score depends heavily on the balance reported at statement close, not how much you cycled mid-month.

- Issuer scrutiny is real: Frequent cycling can trigger fraud alerts, account reviews, or even closures, especially if patterns resemble cash advances or money laundering.

- Safer alternatives exist: Requesting a credit limit increase, opening a new card, or spreading expenses across multiple accounts reduces risk while achieving similar goals.

- Use sparingly, if at all: A one-time cycle for a large purchase may fly under the radar, but habitual cycling is a high-risk, low-reward strategy for most beginners.

What Is Credit Cycling?

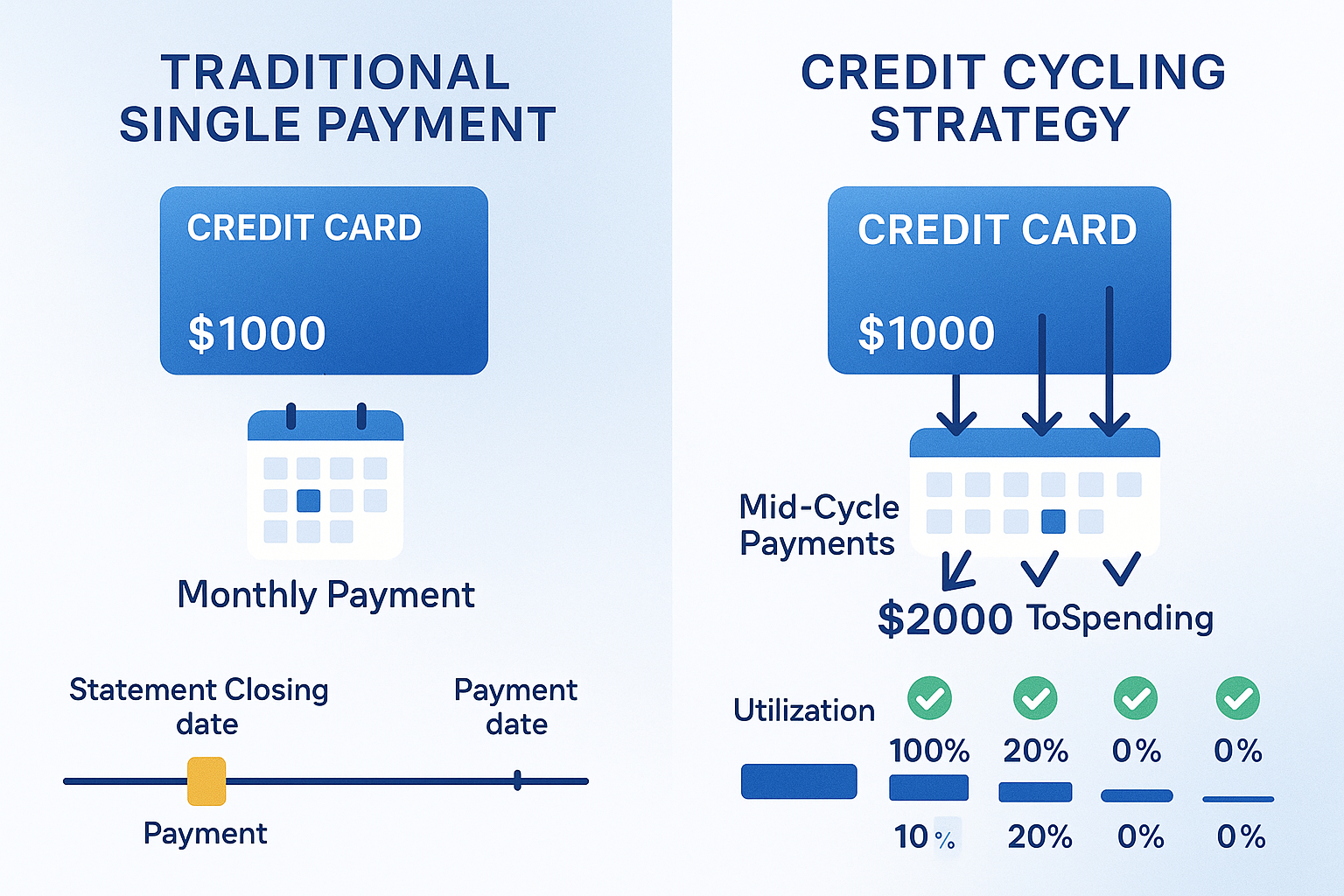

Credit cycling is the practice of making multiple payments to your credit card within a single billing cycle, allowing you to spend more than your credit limit by repeatedly freeing up available credit before your statement closes.

Here’s the plain-English definition: instead of charging $1,000 on a $1,000-limit card and waiting for your statement to close, you might spend $500, pay it off mid-cycle, spend another $500, pay that off, and repeat, effectively cycling through $2,000 or more in purchases while never exceeding your $1,000 limit at any given moment.

The appeal is obvious: you gain increased spending power without requesting a formal credit line increase, you can hit rewards thresholds faster, and if timed correctly, you keep your reported utilization low, which is critical for maintaining a strong credit score.

But the math behind credit cycling reveals a critical flaw: card issuers monitor total monthly spending, not just your statement balance. When your monthly charges far exceed your credit limit, say, $3,000 in purchases on a $1,000 card, it raises algorithmic red flags. Issuers may interpret this pattern as a sign of financial distress, potential fraud, or even money laundering, leading to account restrictions or closures.

Takeaway: Credit cycling is a short-term tactic that exploits the gap between your available credit and your total monthly spending, but it’s not invisible to issuers, and it’s not without consequences.

How Credit Cycling Works (Simple Explanation)

Understanding credit cycling requires grasping two key concepts: billing cycles and statement closing dates. Every credit card operates on a monthly billing cycle, typically 28–31 days. At the end of that cycle, your statement closing date arrives, and your issuer reports your current balance to the credit bureaus. That reported balance determines your credit utilization ratio, which accounts for roughly 30% of your FICO score.

Here’s how credit cycling exploits this system:

- You make a purchase that consumes part of your available credit.

- You pay off that balance before the statement closes, resetting your available credit to the full limit.

- You repeat the process multiple times within the same billing cycle, effectively spending 2x, 3x, or more than your actual limit.

- At statement close, your balance is low (or zero), so your reported utilization stays favorable, even though your total monthly spending was far higher.

Example: How Someone with a $1,000-Limit Card Might Spend $2,000 in One Cycle

Let’s walk through a concrete scenario:

- Credit limit: $1,000

- Billing cycle: March 1–March 31

- Statement closing date: March 31

Timeline:

- March 5: Spend $500 on groceries and gas. Available credit: $500.

- March 10: Pay off the $500 balance. Available credit resets to $1,000.

- March 15: Spend $700 on home repairs. Available credit: $300.

- March 20: Pay off the $700 balance. Available credit resets to $1,000.

- March 28: Spend $800 on a flight and hotel. Available credit: $200.

- March 31 (statement closes): Current balance is $800. Reported utilization: 80%.

In this example, the cardholder spent $2,000 total ($500 + $700 + $800) on a $1,000-limit card. However, because they made two mid-cycle payments, they never exceeded their limit at any single point. The issuer sees $2,000 in monthly charges, double the credit line, which is the hallmark of credit cycling.

Billing Cycles and Statement Closing Date — Why Timing Matters

The statement closing date is the most critical variable in credit cycling. Your issuer reports your balance to the credit bureaus on this date, not continuously throughout the month. Therefore, if you time your payments strategically, paying down your balance just before the statement closes, you can keep your reported utilization low, even if your total spending was high.

But here’s the catch: issuers track total monthly volume, not just the snapshot balance at statement close. If your monthly charges consistently exceed your credit limit, their risk algorithms will flag your account for review, regardless of your reported utilization.

Insight: Credit cycling is a timing game, but it’s one that issuers are increasingly equipped to detect and penalize. The math may work on paper, but the real-world risk often outweighs the short-term benefit.

Credit Cycling vs Credit Utilization

To understand why credit cycling is risky, you must first understand credit utilization and why it’s far more important to your credit score than cycling itself.

What is Credit Utilization?

Credit utilization is the ratio of your current credit card balances to your total available credit, expressed as a percentage. It’s calculated both per-card and across all your cards combined.

Formula:

[Utilization Ratio ={Total Balances / Total Credit Limits x 100]

For example:

- Card A: $300 balance, $1,000 limit → 30% utilization

- Card B: $0 balance, $2,000 limit → 0% utilization

- Overall utilization: $300 / $3,000 = 10%

Credit scoring models (FICO, VantageScore) heavily weight utilization because it’s a strong predictor of credit risk. High utilization signals financial stress; low utilization suggests responsible credit management. Most experts recommend keeping utilization below 30% per card and below 10% overall for optimal scores.

For a deeper dive into how this metric impacts your financial health, see our credit utilization guide.

Why Many Experts Argue That Utilization Is More Important Than Cycling

Here’s the key distinction: credit cycling affects your total monthly spending, but credit utilization affects your credit score. The two are related but not identical.

If you cycle your credit, spending $2,000 on a $1,000 card, but pay it down to $100 before the statement closes, your reported utilization is just 10%. Your score may remain high, but your issuer sees the full $2,000 in charges and may view your behavior as risky.

Conversely, if you spend $900 on a $1,000 card and let it report at 90% utilization, your score will drop, even if you pay in full every month and never cycle.

Why utilization wins:

- Credit bureaus only see the reported balance, not your mid-cycle activity.

- Utilization is recalculated monthly, so lowering it immediately boosts your score.

- Issuers care about risk, and high utilization is a red flag, but so is excessive cycling.

Takeaway: Credit cycling can manipulate your reported utilization, but it doesn’t eliminate issuer scrutiny. Utilization is the score-building metric that matters most; cycling is the risky tactic that can backfire.

Benefits of Credit Cycling

Despite the risks, credit cycling offers several tangible benefits, especially for cardholders with low credit limits, variable expenses, or specific rewards goals. Here’s the data-driven case for when and why cycling might make sense.

Increased Spending Power Without Requesting a Line Increase

For beginners with starter cards (often $300–$1,000 limits), a single unexpected expense—car repair, medical bill, travel—can exceed available credit. Requesting a credit line increase (CLI) is the standard solution, but it often requires a hard inquiry (which temporarily lowers your score) or a waiting period (typically 6+ months after account opening).

Credit cycling bypasses this process: by making a mid-cycle payment, you instantly restore your available credit without issuer approval. This flexibility is valuable for managing cash flow, especially if your income is irregular or you’re building credit from scratch.

Example: You have a $500-limit card and need to buy a $700 laptop for work. Instead of being declined, you charge $500, pay it off the next day, then charge the remaining $200—completing the purchase without a CLI.

Faster Route to Rewards or Sign-Up Bonus Thresholds

Many credit cards offer lucrative sign-up bonuses—e.g., “Spend $3,000 in 3 months, earn 50,000 points.” For cardholders with low limits, hitting that threshold organically may be impossible. Credit cycling allows you to accelerate spending without exceeding your limit.

Math behind the strategy:

- Card limit: $1,000

- Bonus threshold: $3,000 in 90 days

- Without cycling: You can only charge $1,000/month = $3,000 total (barely meeting the threshold).

- With cycling: You charge $1,000, pay it off mid-month, charge another $1,000, hitting $2,000/month = $6,000 in 90 days.

This approach also works for flat cash-back cards (e.g., 2% on all purchases): doubling your monthly spend doubles your rewards, assuming the issuer doesn’t shut you down first.

Flexibility for Variable Monthly Expenses

Freelancers, gig workers, and small business owners often face unpredictable expenses: a $2,000 equipment purchase one month, $500 the next. Credit cycling provides breathing room, allowing you to smooth out cash flow without carrying a balance or paying interest.

Cause and effect: By paying off charges as income arrives (weekly or bi-weekly), you avoid interest while maintaining access to credit for the next expense. This is particularly useful if you’re using a budgeting strategy that aligns payments with income cycles.

Insight: The benefits of credit cycling are real but situational. They work best for one-time scenarios (large purchase, bonus threshold) rather than habitual monthly cycling, which exponentially increases risk.

Risks Every Beginner Should Know

Credit cycling isn’t illegal, but it’s not risk-free either. Issuers have sophisticated fraud-detection systems, and patterns that resemble misuse, or worse, money laundering, can trigger severe consequences. Here’s what every beginner must understand.

Credit-Score Impact If Reporting Catches You at High Balance

Credit cycling’s entire premise relies on timing: you pay down your balance before the statement closes, keeping reported utilization low. But if you miscalculate, or if your issuer reports mid-cycle balances (some do), you could get caught with a high balance on your credit report.

Scenario:

- You spend $2,000 on a $1,000 card, cycling twice.

- You plan to pay it down to $100 before the statement closes on March 31.

- But your issuer unexpectedly reports your balance on March 25, when it’s still $800.

- Result: 80% utilization is reported, tanking your score by 30–50 points.

Most issuers report on the statement closing date, but some report on other dates (e.g., the last day of the month, or randomly). If you’re cycling aggressively, you risk a high-utilization snapshot hitting your credit report.

Data point: According to FICO, utilization above 30% can drop your score by 20–50 points, depending on your overall credit profile. Above 70%, the impact is even steeper.

Risk of Account Closure or Lost Rewards

Card issuers reserve the right to close accounts or revoke rewards for “abuse” or “misuse,” terms defined in your cardholder agreement. Credit cycling, especially frequent, high-volume cycling, can trigger these clauses.

Why issuers care:

- Risk models: Issuers use predictive algorithms to assess default risk. Spending 2–3x your limit monthly signals financial distress, even if you’re paying on time.

- Profitability: Issuers profit from interchange fees (merchant charges) and interest. Cycling increases interchange but also increases default risk, which erodes profitability.

- Rewards liability: If you’re cycling to hit bonus thresholds, the issuer may view this as “gaming the system” and claw back rewards or close your account.

Real-world example: Multiple reports on credit forums (Reddit’s r/churning, MyFICO) document issuers like Chase, American Express, and Citi closing accounts or freezing rewards for suspected cycling, especially when combined with other red flags (e.g., cash advances, balance transfers).

Red Flags for Issuers — Pattern May Resemble Misuse or Money Laundering

Here’s the most serious risk: credit cycling can mimic money laundering or structuring (intentionally breaking up transactions to evade reporting thresholds). While you’re not committing a crime, the pattern, multiple large payments followed by immediate spending, looks suspicious to automated fraud systems.

Red flags that trigger reviews:

- Monthly spending exceeds credit limit by 2x or more (e.g., $3,000 on a $1,000 card).

- Frequent mid-cycle payments (3+ per month, especially large lump sums).

- Payments followed immediately by large purchases (suggests you’re cycling to enable spending, not manage cash flow).

- Cash-like transactions (Venmo, PayPal, money orders) combined with cycling.

Consequence: Issuers may freeze your account pending a financial review, request income verification, or close the account entirely, sometimes without warning.

Takeaway: The math behind credit cycling may seem sound, but the behavioral pattern it creates is a liability. Issuers are incentivized to minimize risk, and cycling, especially habitual cycling, raises too many red flags to ignore.

How Often Should You Cycle Your Credit (If You Do)

If you’re considering credit cycling, frequency and context are everything. Here’s the data-driven framework for when it’s acceptable, and when it crosses into dangerous territory.

When a One-Time Cycle May Be Acceptable

Scenario: You have a $1,000 credit limit and need to make a $1,500 one-time purchase (e.g., emergency car repair, medical expense, or travel booking). You charge $1,000, pay it off the next day, then charge the remaining $500.

Why is this lower-risk?

- Infrequent: A single cycle in a year (or even a quarter) is unlikely to trigger algorithmic red flags.

- Justifiable: If questioned, you can explain it as a cash-flow timing issue, not habitual behavior.

- Low total volume: $1,500 on a $1,000 card is a 1.5x multiplier—high, but not egregious.

Best practices for one-time cycling:

- Pay in full immediately (same day or next day) to minimize the window of high utilization.

- Avoid doing this near the statement closing date to reduce the chance of a high balance being reported.

- Don’t combine with other red-flag behaviors (cash advances, balance transfers, or multiple cards cycled simultaneously).

Why Frequent Cycling Is Riskier — Issuer Scrutiny & Overall Utilization

Scenario: You cycle your $1,000 card every month, spending $2,000–$3,000 monthly by making 3–4 mid-cycle payments.

Why is this high-risk?

- Pattern recognition: Issuers use machine learning to detect abnormal spending patterns. Consistent monthly cycling will flag your account within 2–3 billing cycles.

- Total volume: Spending 2–3x your limit monthly for multiple months is statistically correlated with higher default rates, regardless of payment history.

- Rewards abuse: If you’re cycling to hit bonus thresholds or maximize cash back, issuers may view this as exploitation and revoke rewards.

Data point: Anecdotal reports from credit communities suggest that issuers like Chase and Amex are particularly aggressive in closing accounts for frequent cycling, especially on premium rewards cards.

Insight: If you must cycle, treat it as an emergency tool, not a monthly strategy. The more you cycle, the higher the probability of account closure or lost rewards.

Best Cards (or Card Types) for Credit Cycling

Not all credit cards are equally tolerant of cycling. Here’s a breakdown of which card types and issuers are historically more (or less) likely to penalize the practice.

Low-Limit Cards for Small Budgets

Starter cards (e.g., secured cards, student cards, or subprime offerings) often come with $300–$1,000 limits, making cycling almost inevitable for cardholders with normal monthly expenses.

Examples:

- Discover it® Secured: Popular starter card with limits as low as $200.

- Capital One Platinum: Often issued with $300–$500 limits.

- Credit One Bank cards: Subprime cards with low limits and high fees.

Why these may be more tolerant:

- Expected behavior: Issuers know low-limit cardholders may need to cycle occasionally to manage expenses.

- Lower rewards exposure: These cards typically offer minimal rewards, so cycling doesn’t cost the issuer much.

Caveat: Even starter cards will close accounts for excessive cycling. The key is moderation.

Rewards Cards (Flat Cash Back or Sign-Up Bonuses)

Flat cash-back cards (e.g., Citi Double Cash, Wells Fargo Active Cash) and sign-up bonus cards (e.g., Chase Sapphire Preferred, Amex Gold) are tempting targets for cycling because the rewards scale with spending.

Why are these riskier:

- Higher rewards liability: Cycling to earn 2–5% cash back (or bonus points) directly costs the issuer money.

- Stricter monitoring: Premium cards have more sophisticated fraud detection and are quicker to shut down suspected abuse.

Best practice: If you’re cycling to hit a sign-up bonus, do it once and then stop. Repeated cycling on rewards cards is a fast track to account closure.

Cards/Issuers Historically More Tolerant (With Caveats)

Based on community reports and issuer policies, some banks are more lenient than others—but none officially endorse cycling.

More tolerant (anecdotally):

- Discover: Known for flexible policies and a beginner-friendly approach.

- Capital One: Often issues low-limit cards and may tolerate occasional cycling, but will close accounts for egregious patterns.

Less tolerant (high closure risk):

- Chase: Aggressive in closing accounts for cycling, especially on Sapphire and Freedom cards.

- American Express: Strict fraud detection; cycling combined with other red flags (e.g., cash advances) often results in account reviews or closures.

- Citi: Mixed reports, but premium cards (e.g., Citi Premier) are monitored closely.

Takeaway: No issuer is “safe” for habitual cycling. If you must cycle, choose a low-limit, low-rewards card and keep frequency to an absolute minimum.

Understanding your overall credit mix can also help you manage multiple cards strategically, reducing the need to cycle any single account.

Alternatives to Credit Cycling

Before you cycle, consider these safer, more sustainable strategies for increasing spending power and building credit.

Requesting a Credit-Limit Increase

How it works: Contact your issuer (online, by phone, or via app) and request a higher credit limit. Many issuers offer automatic increases every 6–12 months for accounts in good standing.

Benefits:

- No cycling risk: Legitimately increases your available credit.

- Improves utilization: Higher limit + same spending = lower utilization ratio.

- No mid-cycle payments required: Simplifies cash-flow management.

Drawbacks:

- Hard inquiry risk: Some issuers perform a hard pull, which temporarily lowers your score by 5–10 points.

- Approval not guaranteed: Requires good payment history and stable income.

Best practice: Request a CLI every 6–12 months, especially after income increases or consistent on-time payments. Many issuers (e.g., Discover, Capital One) allow soft-pull requests, which don’t impact your score.

Opening a New Card

How it works: Apply for a second (or third) credit card to increase your total available credit and spread expenses across multiple accounts.

Benefits:

- Instant utilization improvement: Adding a $2,000 card to your existing $1,000 card drops your overall utilization from (say) 50% to 25%, even if your spending stays the same.

- Rewards diversification: You can optimize spending (e.g., 3% on dining, 2% on gas) across multiple cards.

- No cycling needed: Each card has its own limit, eliminating the need to pay mid-cycle.

Drawbacks:

- Hard inquiry: New applications temporarily lower your score.

- Average age of accounts: Opening new cards reduces your average account age, which can hurt your score in the short term.

Best practice: If you’re building credit, space out new applications (every 6+ months) to minimize score impact. See our guide on building credit responsibly for more.

Spreading Expenses Across Multiple Cards

How it works: Instead of cycling one card, distribute your spending across 2–3 cards, keeping each below 30% utilization.

Example:

- Card A: $1,000 limit, $250 balance (25% utilization)

- Card B: $2,000 limit, $500 balance (25% utilization)

- Overall: $750 / $3,000 = 25% utilization

Benefits:

- No cycling risk: You’re using credit normally, not gaming the system.

- Optimal utilization: Keeping each card below 30% maximizes your score.

- Flexibility: You can shift spending between cards based on rewards categories or promotions.

Drawback: Requires managing multiple due dates and balances, which can be complex for beginners. Using a budgeting framework can help keep track of multiple accounts.

Takeaway: Credit cycling is a high-risk shortcut. Requesting a CLI, opening a new card, or spreading expenses are safer, more sustainable ways to achieve the same goals—without jeopardizing your accounts or rewards.

💳 Credit Cycling Risk Calculator

Analyze your cycling pattern and understand the risks

Monthly Cycle Breakdown

Conclusion

Credit cycling is a double-edged sword: it offers short-term flexibility and spending power, but it comes with real, measurable risks that can undermine your long-term financial health. The math behind the strategy is simple: make multiple payments within a billing cycle to reset your available credit, but the consequences are anything but straightforward.

For beginners, the key insight is this: credit cycling is not a credit-building strategy. Your credit score improves through consistent on-time payments, low utilization, and account age, not through gaming your billing cycle. While cycling may help you hit a rewards threshold or manage a one-time large expense, it should never become a habitual practice.

Actionable next steps:

- Evaluate your need: If you’re cycling to manage regular expenses, you likely need a higher credit limit or an additional card, not cycling.

- Request a credit-limit increase: Contact your issuer every 6–12 months to request a CLI. This is the safest, most sustainable way to increase spending power.

- Open a second card: If you’re consistently hitting your limit, adding a new card (with a different issuer) spreads your spending and lowers overall utilization.

- Monitor your utilization: Use your issuer’s app or a free credit-monitoring tool to track your reported utilization. Keep it below 30% per card and 10% overall for optimal scores.

- Avoid habitual cycling: If you must cycle, limit it to once per quarter (or less) and only for one-time, justifiable expenses.

Building credit is a marathon, not a sprint. The strategies that work, on-time payments, low utilization, diversified credit mix, are boring, but they’re also backed by decades of data and evidence-based research. Credit cycling may seem like a shortcut, but in the world of financial literacy and wealth building, shortcuts often lead to dead ends.

Focus on the fundamentals, manage your budget responsibly, and let compound growth, not risky tactics, build your financial future.

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that teaches the math behind money. With a background in financial analysis and a passion for evidence-based investing, Max breaks down complex financial concepts into clear, actionable insights. His work focuses on helping beginners and intermediate investors understand credit, valuation, risk management, and wealth-building strategies through logic, data, and real-world examples. When not analyzing financial markets, Max enjoys teaching financial literacy and exploring the intersection of behavioral economics and personal finance.

Disclaimer

Educational Content Only: This article is provided for informational and educational purposes only. It does not constitute financial, legal, or credit advice. Credit cycling may violate your cardholder agreement and result in account closure, lost rewards, or other penalties. The Rich Guy Math and its authors are not responsible for any actions taken based on this content. Always consult with a qualified financial advisor or credit counselor before making decisions that could impact your credit or financial health. Credit card terms, issuer policies, and credit scoring models are subject to change. Past performance and anecdotal reports do not guarantee future results.

References

[1] FICO, “What’s in my FICO Scores?” myFICO.com, accessed 2025.

[2] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “What is a credit utilization ratio?” CFPB.gov, 2024.

[3] Federal Reserve, “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households,” FederalReserve.gov, 2024.

[4] Experian, “How Does Credit Utilization Affect Credit Scores?” Experian.com, 2024.

[5] MyFICO Forums, “Credit Cycling Experiences and Account Closures,” community discussions, 2023–2025.

[6] American Express Cardholder Agreement, “Prohibited Activities and Account Closure Provisions,” 2024.

[7] Chase Credit Card Agreement, “Terms and Conditions,” Chase.com, 2024.

[8] Investopedia, “Credit Utilization Ratio: Definition and How to Calculate,” Investopedia.com, 2024.

Frequently Asked QuestiosIs credit cycling illegal?

Is credit cycling illegal?

No, credit cycling is not illegal. However, it may violate your cardholder agreement’s terms regarding abuse or misuse, which can lead to account closure or loss of rewards.

Will credit cycling hurt my credit score?

Not directly. If you keep your reported utilization low and pay on time, your score may stay healthy. But if your issuer reports a high balance mid-cycle or closes your account for cycling, your score will drop.

How many times can I use my credit card in a month?

There’s no official limit, but 1–2 cycles per month is generally safe. Cycling 3+ times per month increases your risk of triggering issuer scrutiny.

Can I cycle my credit card to build credit faster?

No. Cycling doesn’t accelerate credit building. Scores improve through on-time payments, low utilization, and account age. Cycling can actually backfire if it results in account closure.

Which credit card issuers allow credit cycling?

No issuer formally allows cycling. Some users report that Discover and Capital One are more tolerant with smaller limits, while Chase and American Express tend to be stricter.

What happens if I get caught credit cycling?

You may face account closure, reward forfeiture, financial reviews requiring income verification, or even being barred from opening future accounts with that issuer.

Is credit cycling the same as paying my card off early?

No. Paying early once per month is normal and beneficial. Credit cycling involves multiple payments and multiple spending rounds within a single billing cycle, which issuers may view as risky behavior.

Should beginners use credit cycling?

Beginners should avoid credit cycling. Better alternatives include requesting a credit-limit increase, adding a second card, or improving budgeting to avoid needing to cycle in the first place.