When Warren Buffett evaluates a potential investment, one of the first numbers he examines is how much debt a company carries relative to its equity. This single metric reveals whether a business operates from a position of financial strength or teeters on the edge of insolvency. The Debt to Equity Ratio cuts through accounting complexity to answer a fundamental question: who really owns this company—the shareholders or the creditors?

Understanding the Debt to Equity Ratio transforms how investors assess risk, compare companies, and build portfolios designed for long-term wealth building. This metric exposes the mathematical relationship between borrowed capital and owner capital, revealing the financial structure that either amplifies returns or magnifies losses.

This guide breaks down the math behind money when it comes to leverage, teaching the exact formula, interpretation frameworks, and practical applications that separate informed investors from those who gamble without understanding the numbers.

Key Takeaways

- The Debt to Equity Ratio measures financial leverage by dividing total liabilities by shareholders’ equity, showing how much debt a company uses relative to owner capital.

- A ratio of 1.5 means $1.50 in debt for every $1 of equity, indicating the company relies more heavily on borrowed funds than shareholder investment.

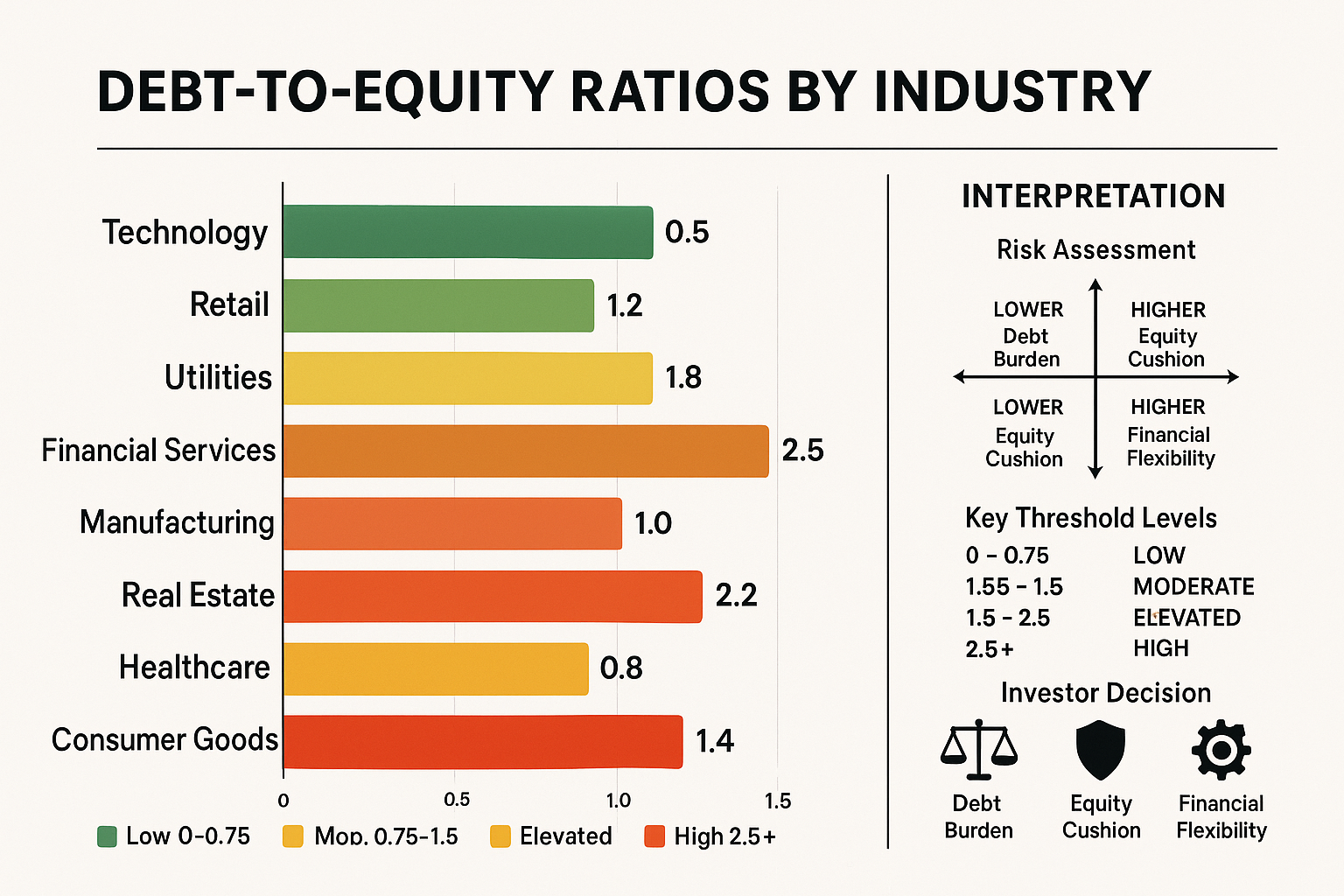

- Industry context matters critically—utilities average 1.8 while technology companies average 0.5, making cross-industry comparisons misleading without adjustment.

- Higher ratios signal increased financial risk through greater interest obligations, reduced flexibility, and amplified volatility during economic downturns.

- All necessary data comes from the balance sheet, making this ratio accessible to any investor who can read financial statements.

What Is the Debt to Equity Ratio?

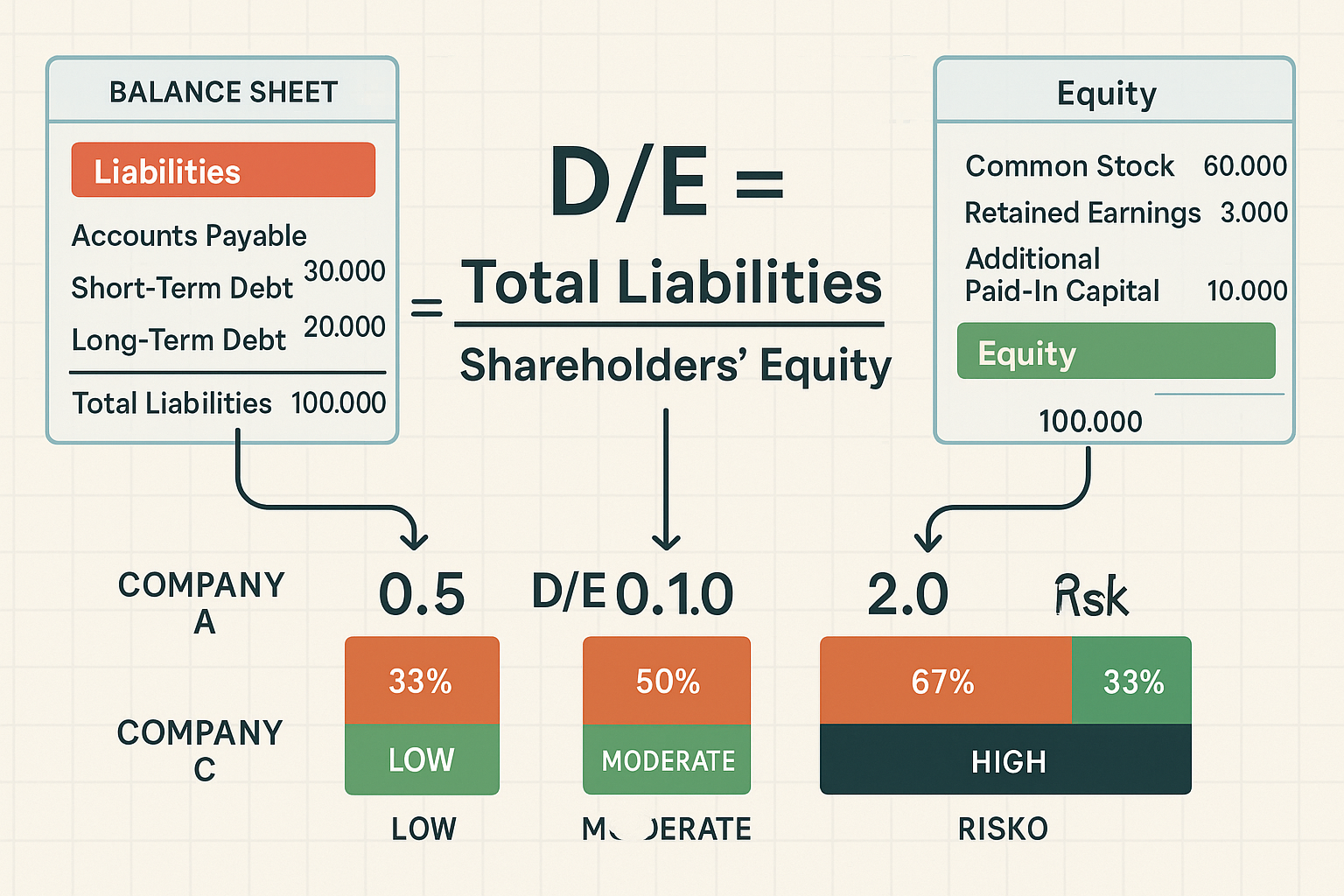

The Debt to Equity Ratio (D/E ratio) is a financial metric that compares a company’s total liabilities to its shareholders’ equity. This ratio quantifies the proportion of company financing that comes from creditors versus owners.

At its core, the D/E ratio answers a simple question: for every dollar of equity invested by shareholders, how many dollars has the company borrowed from lenders?

A company with $500,000 in total liabilities and $250,000 in shareholders’ equity has a D/E ratio of 2.0. This means creditors have provided twice as much financing as shareholders. The company operates with significant leverage, amplifying both potential returns and potential losses.

Why the Debt to Equity Ratio Matters

Financial leverage acts as a multiplier on business performance. When a company generates returns above its cost of debt, leverage accelerates shareholder gains. When returns fall below debt costs, leverage accelerates losses.

The D/E ratio reveals this leverage exposure before problems emerge.

Investors use this metric to assess financial risk because debt creates fixed obligations. Unlike equity holders, who receive dividends only when profits allow, debt holders demand regular interest payments regardless of business performance. Companies with high D/E ratios face greater pressure during revenue downturns because interest payments continue even when cash flow declines.

The ratio also indicates financial flexibility. Companies with low debt levels can borrow additional capital when opportunities arise. Companies already carrying heavy debt loads struggle to access additional financing without paying prohibitive interest rates or diluting existing shareholders through equity issuance.

Insight: The D/E ratio functions as an early warning system for financial distress, revealing vulnerability before it manifests in missed payments or bankruptcy filings.

The Debt to Equity Ratio Formula Explained

The mathematical formula for calculating the Debt to Equity Ratio is straightforward:

D/E Ratio = Total Liabilities ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

Both components come directly from the company’s balance sheet, making this calculation accessible to anyone who can access financial statements through SEC filings or financial data platforms.

Breaking Down Total Liabilities

Total liabilities represent all financial obligations a company owes to external parties. This includes both short-term and long-term obligations.

Short-term liabilities (current liabilities) include:

- Accounts payable owed to suppliers

- Short-term debt due within one year

- Accrued expenses like wages and taxes

- Deferred revenue from advance customer payments

Long-term liabilities include:

- Bonds payable

- Long-term bank loans

- Pension obligations

- Deferred tax liabilities

The balance sheet lists total liabilities as a single line item, aggregating all these obligations. For the D/E ratio calculation, use this total liabilities figure without adjustment.

Understanding Shareholders’ Equity

Shareholders’ equity represents the residual ownership interest in company assets after subtracting all liabilities. This is the book value of shareholder ownership.

The fundamental accounting equation states:

Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity

Rearranging this equation:

Shareholders’ Equity = Assets – Liabilities

Equity consists of:

- Common stock (par value of issued shares)

- Additional paid-in capital (amount paid above par value)

- Retained earnings (cumulative profits not distributed as dividends)

- Treasury stock (shares repurchased by the company, shown as negative)

- Other comprehensive income

The balance sheet reports total shareholders’ equity as a single figure, making the calculation straightforward.

Step-by-Step Calculation Example

Consider a company with the following balance sheet data:

Total Assets: $10,000,000

Total Liabilities: $6,000,000

Shareholders’ Equity: $4,000,000

D/E Ratio = $6,000,000 ÷ $4,000,000 = 1.5

This ratio of 1.5 indicates the company carries $1.50 in debt for every $1.00 of equity. Creditors have provided 60% of the financing ($6M ÷ $10M), while shareholders have provided 40% ($4M ÷ $10M).

How to Calculate Debt to Equity Ratio: Practical Steps

Calculating the D/E ratio requires accessing a company’s most recent balance sheet. Public companies file quarterly (10-Q) and annual (10-K) reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission, available through the SEC EDGAR database.

Step 1: Locate the Balance Sheet

Navigate to the company’s most recent 10-K annual report or 10-Q quarterly report. The balance sheet appears as one of three primary financial statements, alongside the income statement and cash flow statement.

Balance sheets present data as of a specific date (e.g., “As of December 31, 2025”), unlike income statements, which cover a period.

Step 2: Find Total Liabilities

Scan the balance sheet for the line item labeled “Total Liabilities” or “Total Liabilities and Shareholders’ Equity.” This figure appears approximately halfway down the statement, separating the liabilities section from the equity section.

If the balance sheet separates current and non-current liabilities, add these subtotals:

Total Liabilities = Current Liabilities + Non-Current Liabilities

Record this number precisely, including all decimal places for accuracy.

Step 3: Find Shareholders’ Equity

Locate “Total Shareholders’ Equity” or “Total Stockholders’ Equity” near the bottom of the balance sheet. This represents the ownership interest after all liabilities are satisfied.

Some balance sheets label this section “Equity” or “Net Assets.” Regardless of terminology, this figure represents assets minus liabilities.

Step 4: Perform the Division

Divide total liabilities by shareholders’ equity:

D/E Ratio = Total Liabilities ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

Express the result as a decimal to two places (e.g., 1.47) or as a ratio (e.g., 1.47:1).

Step 5: Verify Your Calculation

Cross-check your result by calculating the equity multiplier:

Equity Multiplier = Total Assets ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

The relationship between these metrics is:

D/E Ratio = Equity Multiplier – 1

If your D/E ratio is 1.5, the equity multiplier should be 2.5. This verification confirms calculation accuracy.

Practical Tip: Always use figures from the same reporting date. Mixing data from different quarters creates inconsistencies that distort the ratio.

Interpreting Debt to Equity Ratio Results

A calculated D/E ratio means nothing without proper interpretation. The same ratio signals strength in one industry and weakness in another.

What Different Ratios Mean

D/E Ratio < 1.0: The company has more equity than debt. Shareholders have invested more capital than creditors have lent. This suggests conservative financing, lower financial risk, and greater ability to weather economic downturns.

D/E Ratio = 1.0: Debt and equity are balanced. Creditors and shareholders have equal stakes in company assets. This represents moderate leverage with balanced risk.

D/E Ratio > 1.0: Debt exceeds equity. The company relies more heavily on borrowed capital than shareholder investment. This amplifies returns during growth periods but increases bankruptcy risk during downturns.

D/E Ratio > 2.0: High leverage signals significant financial risk. The company carries more than twice as much debt as equity, creating substantial interest obligations and limited financial flexibility.

The Risk-Return Tradeoff

Higher D/E ratios amplify both gains and losses through the mechanism of financial leverage.

Consider two companies, each with $1,000,000 in assets generating 10% annual returns ($100,000 in operating income):

Company A (Conservative):

- Equity: $900,000

- Debt: $100,000 at 5% interest

- Interest expense: $5,000

- Net income to shareholders: $95,000

- Return on equity: 10.6%

Company B (Aggressive):

- Equity: $300,000

- Debt: $700,000 at 5% interest

- Interest expense: $35,000

- Net income to shareholders: $65,000

- Return on equity: 21.7%

Company B’s higher leverage (D/E = 2.33 vs. 0.11) doubles the return on equity during profitable periods.

Now consider a recession where operating income falls to $30,000:

Company A:

- Interest expense: $5,000

- Net income: $25,000

- Return on equity: 2.8%

Company B:

- Interest expense: $35,000

- Net income: -$5,000 (loss)

- Return on equity: -1.7%

The same leverage that amplified gains now amplifies losses. Company B’s shareholders experience negative returns while Company A’s shareholders maintain positive returns despite the downturn.

This mathematical relationship explains why risk management requires understanding leverage ratios before investing.

Industry-Specific Benchmarks

Average D/E ratios vary dramatically across industries based on business models, asset types, and cash flow stability.

Capital-Intensive Industries (High D/E):

- Utilities: 1.5 – 2.0

- Telecommunications: 1.2 – 1.8

- Real Estate: 1.5 – 2.5

- Airlines: 1.0 – 2.0

These industries require massive infrastructure investments and generate stable, predictable cash flows that support higher debt levels.

Asset-Light Industries (Low D/E):

- Technology: 0.2 – 0.8

- Software: 0.1 – 0.5

- Consulting: 0.3 – 0.7

- Biotechnology: 0.2 – 0.9

These industries require minimal physical assets and face uncertain revenue streams, making high debt levels dangerous.

Manufacturing and Retail (Moderate D/E):

- Consumer goods: 0.8 – 1.5

- Automotive: 1.0 – 1.8

- Retail: 0.7 – 1.3

These industries balance asset requirements with revenue stability, supporting moderate leverage.

Insight: Never compare a technology company’s D/E ratio to a utility company’s ratio. Industry context determines whether a ratio signals strength or weakness.

Variations of the Debt to Equity Ratio

The basic D/E ratio provides valuable insight, but variations offer more nuanced analysis for specific situations.

Interest-Bearing Debt to Equity

This variation excludes non-interest-bearing liabilities like accounts payable and deferred revenue, focusing exclusively on debt that requires interest payments.

Interest-Bearing D/E = Interest-Bearing Debt ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

Interest-bearing debt includes:

- Short-term borrowings

- Current portion of long-term debt

- Long-term debt

- Bonds payable

- Capital leases

This variation provides a clearer picture of financial risk because interest payments create fixed cash obligations regardless of business performance. Accounts payable and other operating liabilities fluctuate with business activity and don’t require interest payments.

A company might have a total D/E ratio of 2.0 but an interest-bearing D/E ratio of only 1.0 if half its liabilities consist of accounts payable. The interest-bearing ratio better reflects true financial leverage.

Net Debt to Equity

Net debt adjusts for cash and cash equivalents, recognizing that companies with substantial cash reserves can immediately pay down debt if needed.

Net Debt to Equity = (Total Debt – Cash and Cash Equivalents) ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

This variation proves especially useful for:

- Companies with seasonal cash flows

- Businesses holding large cash reserves

- Firms preparing for acquisitions

- Organizations with upcoming debt maturities

A company with $1,000,000 in debt, $400,000 in cash, and $500,000 in equity has:

- Total D/E: 2.0

- Net D/E: 1.2

The net D/E ratio of 1.2 better reflects actual financial risk because the company could use its cash to reduce debt to $600,000 immediately.

Long-Term Debt to Equity

This variation focuses exclusively on long-term obligations, excluding current liabilities that will be satisfied within one year.

Long-Term D/E = Long-Term Debt ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

Long-term debt represents the company’s permanent capital structure rather than temporary working capital needs. This metric helps assess:

- Capital structure strategy

- Long-term financial stability

- Refinancing risk over extended periods

A company might maintain high current liabilities due to rapid growth while keeping long-term debt minimal. The long-term D/E ratio reveals this conservative capital structure that the total D/E ratio might obscure.

Using the Debt to Equity Ratio for Investment Decisions

Savvy investors integrate the D/E ratio into comprehensive analysis frameworks rather than relying on this single metric in isolation.

Screening for Financial Stability

The D/E ratio serves as an effective initial screen when building investment watchlists. Setting maximum D/E thresholds filters out companies carrying excessive leverage before deeper analysis begins.

Conservative investors might screen for:

- D/E < 0.5 for maximum safety

- D/E < 1.0 for moderate risk tolerance

- D/E < 1.5 for growth-oriented portfolios

These screens eliminate companies with capital structures misaligned with investment objectives, saving analysis time.

Comparing Competitors

The D/E ratio reveals competitive positioning within industries. Companies with lower leverage than competitors possess strategic advantages:

Greater Financial Flexibility: Low-debt companies can borrow for acquisitions, expansion, or competitive battles when opportunities arise.

Stronger Recession Resistance: During economic downturns, low-debt companies maintain operations while high-debt competitors face bankruptcy risk.

Lower Capital Costs: Companies with strong balance sheets access capital at lower interest rates, improving profitability.

When analyzing two retail companies, one with a D/E of 0.6 and another with a D/E of 2.1, the lower-leverage company demonstrates superior financial management and lower risk, all else equal.

Trend Analysis Over Time

A single D/E ratio provides a snapshot. Tracking the ratio across multiple quarters reveals whether management is strengthening or weakening the balance sheet.

Declining D/E (Improving):

- Management is paying down debt

- Equity grows through retained earnings

- Strengthening financial position

- Reducing financial risk

Rising D/E (Deteriorating):

- Increasing borrowing

- Declining equity from losses

- Weakening financial position

- Increasing financial risk

A company with D/E rising from 0.8 to 1.2 to 1.6 over three years signals deteriorating financial health, even if the current 1.6 ratio appears acceptable in isolation.

Combining with Other Financial Ratios

The D/E ratio works best alongside complementary metrics that provide additional context:

Interest Coverage Ratio: Measures how many times operating income covers interest expense, revealing whether the company generates sufficient cash to service its debt.

Current Ratio: Compares current assets to current liabilities, showing short-term liquidity independent of capital structure.

Return on Equity (ROE): Shows whether leverage amplifies returns effectively or simply increases risk without corresponding gains.

A company with a D/E of 2.0, interest coverage of 8.0, and ROE of 18% uses leverage effectively. A company with a D/E of 2.0, interest coverage of 1.5, and Return On Equity of 6% carries dangerous leverage that doesn’t generate adequate returns.

Understanding how financial ratios interact creates comprehensive analysis frameworks that individual metrics cannot provide.

Red Flags to Watch For

Certain D/E ratio patterns signal serious problems:

Rapidly Increasing Ratio: Debt growing faster than equity suggests deteriorating operations, aggressive expansion, or poor capital allocation.

Negative Equity: When liabilities exceed assets, shareholders’ equity becomes negative, making the D/E ratio meaningless. This signals severe financial distress.

Industry Outliers: A technology company with a D/E of 3.0 or a utility with a D/E of 0.3 deviates dramatically from industry norms, warranting investigation.

Inconsistent Reporting: Companies that frequently restate balance sheets or change accounting methods may be obscuring true leverage levels.

Real-World Examples of Debt to Equity Analysis

Examining actual companies demonstrates how the D/E ratio functions in practice.

Example 1: Apple Inc. (Technology)

Apple historically maintains a conservative balance sheet despite having the capacity to borrow extensively.

Recent Balance Sheet Data (Simplified):

- Total Assets: $353 billion

- Total Liabilities: $290 billion

- Shareholders’ Equity: $63 billion

- D/E Ratio: 4.6

This high ratio appears alarming until examining the composition. Apple’s liabilities include:

- $120 billion in deferred revenue and other non-debt liabilities

- $110 billion in long-term debt

- $60 billion in other liabilities

The interest-bearing D/E ratio tells a different story:

- Interest-Bearing Debt: $110 billion

- Shareholders’ Equity: $63 billion

- Interest-Bearing D/E: 1.7

Even this ratio seems elevated for technology, but Apple holds $48 billion in cash and marketable securities:

- Net Debt: $62 billion ($110B – $48B)

- Net D/E: 0.98

The net D/E ratio of 0.98 reveals Apple’s true financial position: essentially balanced leverage with the ability to eliminate debt if management chose to deploy cash reserves.

This example demonstrates why examining ratio variations and understanding balance sheet composition matter more than accepting the headline D/E figure.

Example 2: NextEra Energy (Utility)

Utilities operate with high leverage by design because regulated rates and stable cash flows support substantial debt.

Recent Balance Sheet Data (Simplified):

- Total Assets: $170 billion

- Total Liabilities: $115 billion

- Shareholders’ Equity: $55 billion

- D/E Ratio: 2.1

This 2.1 ratio appears high in absolute terms but falls within normal utility industry ranges. The company’s business model justifies this leverage:

Predictable Cash Flows: Regulated electricity rates generate stable revenue regardless of economic conditions.

Hard Assets: Power plants and transmission infrastructure serve as collateral for debt.

Regulatory Framework: Rate structures ensure the company can service debt obligations.

NextEra’s interest coverage ratio of 4.2 confirms the company generates operating income more than four times its interest expense, indicating sustainable leverage despite the high D/E ratio.

Example 3: Declining Retailer (Warning Signs)

Consider a hypothetical retail company showing deteriorating fundamentals:

Year 1:

- Total Liabilities: $400 million

- Shareholders’ Equity: $600 million

- D/E Ratio: 0.67

Year 2:

- Total Liabilities: $500 million

- Shareholders’ Equity: $550 million

- D/E Ratio: 0.91

Year 3:

- Total Liabilities: $650 million

- Shareholders’ Equity: $450 million

- D/E Ratio: 1.44

The D/E ratio more than doubled in three years, signaling serious problems. Investigating further reveals:

- Debt increased by $250 million (62.5%)

- Equity declined by $150 million (25%)

- The company borrowed to cover operating losses

- Retained earnings turned negative

This pattern indicates a company burning through equity while accumulating debt to fund operations—a clear warning sign for investors to avoid or exit positions.

Common Mistakes When Using the Debt-to-Equity Ratio

Even experienced investors make errors when calculating or interpreting this metric.

Mistake 1: Ignoring Industry Context

Comparing D/E ratios across different industries produces meaningless conclusions. A software company with a D/E of 1.2 carries excessive leverage, while a utility with the same ratio operates conservatively.

Always compare companies to industry peers rather than absolute standards. A ratio that signals strength in one sector indicates weakness in another.

Mistake 2: Using Inconsistent Data

Mixing figures from different reporting periods distorts calculations. Using Q3 liabilities with Q4 equity creates an invalid ratio.

Always verify that all balance sheet components come from the same date. Annual reports provide year-end figures, while quarterly reports provide interim snapshots.

Mistake 3: Overlooking Off-Balance-Sheet Obligations

Some liabilities don’t appear on balance sheets, including:

- Operating leases (pre-2019 accounting standards)

- Pension obligations (sometimes footnoted rather than recognized)

- Contingent liabilities from lawsuits

- Joint venture obligations

These hidden obligations increase true leverage beyond what the D/E ratio reveals. Reading financial statement footnotes uncovers these items.

Mistake 4: Treating All Debt Equally

Not all debt carries equal risk. Consider:

- Fixed vs. variable interest rates

- Short-term vs. long-term maturities

- Secured vs. unsecured debt

- Covenant restrictions

A company with $100 million in 2% fixed-rate 30-year bonds faces less risk than a company with $100 million in variable-rate debt due in two years, even though both show identical D/E ratios.

Mistake 5: Ignoring Equity Quality

Shareholders’ equity quality varies significantly:

- Tangible equity (real assets) vs. intangible equity (goodwill)

- Positive retained earnings vs. accumulated losses

- Common equity vs. preferred equity

A company with $500 million in equity consisting entirely of goodwill from acquisitions has weaker equity than a company with $500 million in retained earnings from profitable operations.

Calculating the tangible D/E ratio (excluding intangible assets from equity) provides a more conservative measure:

Tangible D/E = Total Liabilities ÷ (Shareholders’ Equity – Intangible Assets)

The Debt to Equity Ratio and Capital Structure Strategy

Management teams actively manage D/E ratios as part of broader capital structure optimization.

The Optimal Capital Structure Theory

Financial theory suggests an optimal capital structure exists where the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is minimized. This occurs when the tax benefits of debt (interest is tax-deductible) balance against the increased bankruptcy risk from excessive leverage.

The optimal D/E ratio varies by:

- Industry characteristics

- Business cycle position

- Growth opportunities

- Asset tangibility

- Profitability stability

Companies target D/E ratios that minimize capital costs while maintaining financial flexibility for strategic opportunities.

How Companies Adjust Their D/E Ratio

Management can increase or decrease the D/E ratio through various actions:

To Decrease D/E (Deleverage):

- Pay down debt using cash flow

- Issue new equity through stock offerings

- Retain earnings rather than paying dividends

- Sell assets and use proceeds to retire debt

To Increase D/E (Leverage Up):

- Issue new bonds or take bank loans

- Repurchase shares (reducing equity)

- Pay special dividends (reducing retained earnings)

- Fund acquisitions with debt

Share buybacks deserve special attention. When companies repurchase stock, they reduce shareholders’ equity, which increases the D/E ratio even if debt remains constant.

Consider a company with $100 million in debt and $100 million in equity (D/E = 1.0). If management repurchases $20 million in stock:

- Debt: $100 million (unchanged)

- Equity: $80 million

- New D/E: 1.25

The D/E ratio increased 25% without the company borrowing a single additional dollar.

Leverage and the Economic Cycle

Sophisticated management teams adjust leverage strategically across economic cycles:

During Expansions:

- Increase leverage to fund growth

- Take advantage of low interest rates

- Invest in capacity expansion

During Recessions:

- Reduce leverage to increase safety

- Build cash reserves

- Avoid financial distress

Companies that maintain low D/E ratios during expansions position themselves to acquire distressed competitors during recessions when high-leverage companies face bankruptcy.

Understanding these patterns helps investors evaluate whether management makes prudent capital structure decisions or takes excessive risks.

Advanced Applications of the Debt-to-Equity Ratio

Sophisticated investors extend basic D/E analysis into more complex frameworks.

DuPont Analysis Integration

The DuPont framework decomposes return on equity (ROE) into three components:

ROE = Profit Margin × Asset Turnover × Equity Multiplier

The equity multiplier equals:

Equity Multiplier = Total Assets ÷ Shareholders’ Equity = 1 + D/E Ratio

This relationship shows how leverage directly amplifies ROE. A company with a D/E of 2.0 has an equity multiplier of 3.0, tripling the ROE that profit margin and asset turnover would generate alone.

DuPont analysis reveals whether high ROE stems from operational excellence (profit margin and asset turnover) or simply from financial leverage. Investors prefer the former because it’s sustainable, while leverage-driven ROE increases risk without improving underlying business performance.

Credit Risk Assessment

Credit analysts use the D/E ratio as a primary input for credit ratings and default probability models.

Higher D/E ratios correlate with:

- Lower credit ratings (BBB vs. AAA)

- Higher default probabilities

- Wider credit spreads

- Higher borrowing costs

The relationship isn’t linear. Moving from D/E of 0.5 to 1.0 has minimal impact on credit quality, while moving from 2.0 to 2.5 can trigger rating downgrades and materially increase borrowing costs.

Understanding this dynamic helps investors anticipate when companies might face refinancing challenges or credit market access problems.

Acquisition Analysis

When evaluating potential acquisitions, the D/E ratio reveals:

Target Company Risk: High-leverage targets require more equity financing or carry greater integration risk.

Acquirer Capacity: The acquirer’s D/E ratio determines how much debt it can assume without overleveraging.

Post-Merger Capital Structure: Combining balance sheets might create unsustainable leverage requiring immediate deleveraging.

Private equity firms particularly focus on D/E ratios because they typically finance acquisitions with substantial debt. A target company with an existing D/E of 2.0 offers less capacity for additional leverage than a target with a D/E of 0.3.

The Relationship Between Debt to Equity and Other Key Metrics

The D/E ratio connects to numerous other financial metrics through mathematical relationships.

Debt Ratio

The debt ratio expresses leverage as a percentage of total assets:

Debt Ratio = Total Liabilities ÷ Total Assets

The relationship between the debt ratio and the D/E ratio is:

D/E Ratio = Debt Ratio ÷ (1 – Debt Ratio)

A company with a debt ratio of 60% has:

- D/E = 0.60 ÷ (1 – 0.60) = 0.60 ÷ 0.40 = 1.5

Both metrics measure the same concept from different perspectives.

Equity Multiplier

The equity multiplier shows how many dollars of assets each dollar of equity supports:

Equity Multiplier = Total Assets ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

The mathematical relationship is:

Equity Multiplier = 1 + D/E Ratio

A D/E ratio of 1.5 corresponds to an equity multiplier of 2.5, meaning each dollar of equity supports $2.50 in total assets.

Times Interest Earned

While the D/E ratio measures leverage, the times interest earned (TIE) ratio measures the ability to service that debt:

TIE = Operating Income ÷ Interest Expense

These metrics work together:

- D/E shows how much leverage exists

- TIE shows whether the company generates sufficient income to service that leverage

A company with a D/E of 2.0 and a TIE of 8.0 uses leverage safely. A company with a D/E of 2.0 and TIE of 1.2 teeters on the edge of financial distress.

Free Cash Flow Coverage

The ultimate test of sustainable leverage is whether free cash flow covers debt service obligations.

Free Cash Flow Debt Coverage = Free Cash Flow ÷ Total Debt

This ratio shows what percentage of total debt the company could repay annually using free cash flow. Higher percentages indicate safer leverage regardless of the D/E ratio level.

A utility with a D/E of 2.5 but free cash flow coverage of 15% maintains sustainable leverage. A retailer with a D/E of 1.0 but free cash flow coverage of 3% faces greater financial risk despite the lower D/E ratio.

How to Find Debt-to-Equity Ratio Data

Investors can access D/E ratio data through multiple channels without performing manual calculations.

Financial Data Platforms

Major financial websites calculate and display D/E ratios automatically:

Yahoo Finance: Search for any stock ticker, navigate to “Statistics,” and find the D/E ratio in the “Balance Sheet” section.

Google Finance: Enter a ticker symbol and select “Financials” to view key ratios, including D/E.

Morningstar: Provides D/E ratios along with industry comparisons and historical trends.

Bloomberg Terminal: Professional-grade platform offering D/E ratios with extensive customization and peer comparisons (subscription required).

These platforms save calculation time but may use slightly different methodologies (total debt vs. interest-bearing debt), so understanding the underlying formula remains important.

SEC Filings

For the most accurate data, access source documents:

- Navigate to SEC.gov/edgar

- Search for the company name or ticker

- Open the most recent 10-K (annual) or 10-Q (quarterly) filing

- Locate the Consolidated Balance Sheet

- Extract Total Liabilities and Shareholders’ Equity figures

- Calculate the ratio manually

This approach guarantees accuracy and allows for customized variations (net debt, interest-bearing debt, etc.) that automated platforms might not offer.

Brokerage Research

Most brokerage platforms provide research reports that include:

- Current D/E ratios

- Historical trends

- Industry comparisons

- Analyst commentary on capital structure

These reports contextualize the raw numbers, explaining whether management is strengthening or weakening the balance sheet and how the company compares to competitors.

Building a Personal Investment Framework Using the Debt-to-Equity Ratio

Successful investors develop systematic frameworks that incorporate the D/E ratio into broader decision processes.

Setting Personal Risk Tolerances

Define maximum acceptable D/E ratios based on investment objectives:

Conservative Portfolio (Preservation Focus):

- Maximum D/E: 0.75

- Emphasis on financial stability

- Suitable for retirement accounts or risk-averse investors

Balanced Portfolio (Growth and Income):

- Maximum D/E: 1.5

- Moderate leverage acceptable

- Suitable for long-term wealth building

Aggressive Portfolio (Maximum Growth):

- Maximum D/E: 2.5

- Higher leverage is tolerated for growth potential

- Suitable for younger investors with long-term horizons

These thresholds should be adjusted by the industry. A conservative investor might accept a D/E of 2.0 for utilities while rejecting a D/E of 1.0 for technology companies.

Creating a Screening Checklist

Develop a systematic checklist that includes the D/E ratio alongside other critical metrics:

D/E Ratio: Below industry average or personal threshold

D/E Trend: Stable or declining over the past 3 years

Interest Coverage: Above 3.0

Current Ratio: Above 1.5

Free Cash Flow: Positive for the past 3 years

ROE: Above 12% and exceeding cost of equity

Companies passing all criteria advance to deeper analysis. Those failing multiple criteria get eliminated immediately.

This systematic approach prevents emotional decision-making and ensures consistent application of evidence-based investing principles.

Monitoring Existing Holdings

For companies already in the portfolio, track D/E ratio changes quarterly:

Green Flag (Hold/Buy More):

- D/E declining or stable

- Ratio remains below industry average

- Management commentary indicates prudent capital allocation

Yellow Flag (Monitor Closely):

- D/E increasing moderately

- Ratio approaching industry average

- Management is indicating temporary leverage for a specific project

Red Flag (Consider Selling):

- D/E increasing rapidly (>20% annually)

- Ratio exceeding industry average

- Management provides vague explanations

- Interest coverage is declining simultaneously

Regular monitoring catches deteriorating financial health before it manifests in stock price declines, allowing investors to exit positions while preserving capital.

The Debt-to-Equity Ratio in Different Investment Strategies

Different investment approaches weigh the D/E ratio differently based on strategy objectives.

Value Investing

Value investors typically prefer low D/E ratios because:

- Strong balance sheets provide a margin of safety

- Low leverage reduces bankruptcy risk during market downturns

- Financial flexibility allows companies to repurchase undervalued shares

Warren Buffett famously avoids highly leveraged companies, seeking businesses that could survive extended periods without access to capital markets. This preference for financial strength over maximum returns reflects value investing’s emphasis on capital preservation.

Growth Investing

Growth investors often tolerate higher D/E ratios because:

- Rapidly growing companies often outpace their equity base

- Debt can fund expansion more quickly than retained earnings

- Future growth will reduce leverage ratios naturally

However, even growth investors distinguish between:

- Productive leverage: Debt funding expansion that generates returns exceeding borrowing costs

- Desperate leverage: Debt covering operating losses or poor capital allocation

The former is acceptable; the latter signals trouble regardless of growth rates.

Dividend Investing

Dividend investors scrutinize D/E ratios because:

- High debt service reduces cash available for dividends

- Overleveraged companies often cut dividends during downturns

- Sustainable dividends require financial flexibility

Dividend aristocrats—companies that have increased dividends for 25+ consecutive years—typically maintain conservative D/E ratios below 1.0, demonstrating that dividend sustainability requires balance sheet strength.

Income Investing

Income investors seeking yield from bonds or preferred stocks examine D/E ratios from the creditor perspective:

- Lower D/E ratios reduce default risk

- Higher D/E ratios increase yields but also increase risk

- Optimal positioning balances yield requirements against safety needs

Investment-grade bonds typically come from companies with D/E ratios below 2.0, while high-yield bonds often come from companies with D/E ratios above 3.0.

Limitations of the Debt to Equity Ratio

Despite its usefulness, the D/E ratio has important limitations that investors must understand.

Accounting Differences

Different accounting standards and practices affect reported figures:

GAAP vs. IFRS: U.S. companies use Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), while international companies often use International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These frameworks treat certain items differently, making cross-border comparisons challenging.

Lease Accounting: Changes to lease accounting standards in 2019 brought operating leases onto balance sheets, increasing reported liabilities and D/E ratios without changing actual obligations.

Goodwill and Intangibles: Acquisitions create goodwill that inflates equity without representing tangible assets, potentially understating true leverage.

Market Value vs Book Value

The D/E ratio uses book values from balance sheets, but market values often differ dramatically:

Equity Market Value: Public companies’ equity market value equals share price times shares outstanding, often differing substantially from book value.

Debt Market Value: Bond prices fluctuate based on interest rates and credit quality, creating market values that diverge from book values.

Market-value D/E ratios provide different insights:

Market D/E = Market Value of Debt ÷ Market Value of Equity

A company with a book D/E of 1.0 might have a market D/E of 0.5 if its stock price has doubled since equity was initially raised, indicating lower actual leverage than the book ratio suggests.

Timing Issues

Balance sheets represent a single point in time, potentially missing important dynamics:

- Seasonal businesses show dramatically different ratios at year-end vs. mid-year

- Recent acquisitions or divestitures create temporary distortions

- One-time events can skew ratios for a single reporting period

Examining multiple quarters smooths these timing issues and reveals true trends.

Industry Disruption

Historical industry benchmarks become less relevant during periods of disruption. The retail industry’s traditional D/E benchmarks meant little as e-commerce transformed the sector, making historical comparisons misleading.

Investors must adjust expectations when analyzing companies in industries undergoing fundamental change.

📊 Debt to Equity Ratio Calculator

Calculate and interpret your company’s financial leverage

Conclusion: Mastering the Math Behind Leverage

The Debt to Equity Ratio transforms abstract balance sheet figures into actionable insight about financial risk and capital structure. This single metric reveals whether a company operates from a position of strength or vulnerability, whether management allocates capital prudently or recklessly, and whether shareholders face amplified returns or amplified risks.

Understanding the D/E ratio requires more than memorizing a formula. It demands:

Industry Context: Recognizing that 1.5 signals strength in utilities but weakness in technology.

Trend Analysis: Tracking changes over multiple quarters to identify improving or deteriorating financial health.

Comprehensive Integration: Combining D/E with interest coverage, free cash flow, and profitability metrics for complete analysis.

Variation Application: Calculating interest-bearing and net D/E ratios when standard calculations obscure true leverage.

The math behind money reveals that leverage functions as a double-edged sword—amplifying gains during prosperity while magnifying losses during adversity. Companies that maintain appropriate leverage for their industry and business model position themselves for sustainable wealth building over decades. Those that overleverage chase short-term returns at the expense of long-term survival.

Next Steps for Investors

1. Calculate D/E ratios for current holdings: Review the balance sheets of companies in your portfolio and calculate their D/E ratios. Compare these to industry averages and historical trends.

2. Establish personal thresholds: Define maximum acceptable D/E ratios based on your risk tolerance and investment timeline. Create screening criteria that align with your investment philosophy.

3. Monitor quarterly changes: Set calendar reminders to review D/E ratios when companies release quarterly earnings. Track changes in a spreadsheet to identify trends before they become problems.

4. Compare competitors: When evaluating new investments, calculate D/E ratios for all major competitors in the industry. The company with the strongest balance sheet often outperforms during economic downturns.

5. Study variations: Practice calculating interest-bearing D/E and net D/E for companies with complex balance sheets. Understanding these variations reveals insights that standard calculations miss.

The Debt to Equity Ratio represents one component of comprehensive financial analysis, but it’s a critical component. Master this metric, integrate it into systematic decision frameworks, and combine it with valuation principles to build a portfolio positioned for long-term success through all market conditions.

Financial literacy begins with understanding the numbers. The D/E ratio provides a clear, quantifiable measure of financial risk that every investor can calculate, interpret, and apply to make better investment decisions.

About the Author

Max Fonji is a data-driven financial educator and the founder of The Rich Guy Math. With a background in financial analysis and a passion for teaching the mathematical principles behind wealth building, Max breaks down complex financial concepts into clear, actionable insights. His evidence-based approach helps investors understand not just what the numbers say, but why they matter and how to use them for better decision-making. Max believes that financial literacy starts with understanding the math behind money—and that anyone can learn to invest successfully through data, logic, and disciplined analysis.

Educational Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. The content represents the author’s analysis and opinions based on publicly available information and should not be considered personalized investment recommendations.

Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results. The Debt to Equity Ratio is one of many metrics investors should consider when evaluating securities, and no single metric provides complete information for investment decisions.

Different investors have different financial situations, risk tolerances, time horizons, and investment objectives. Before making any investment decisions, consult with qualified financial, tax, and legal professionals who can provide advice tailored to your specific circumstances.

The examples and calculations in this article are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent recommendations to buy or sell any specific securities. Company data and financial ratios change over time, and readers should verify all figures using current financial statements before making investment decisions.

The Rich Guy Math and its authors do not assume any liability for financial decisions made based on information in this article. Readers are solely responsible for their own investment research and decisions.

References

[1] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “Beginners’ Guide to Financial Statements.” SEC.gov. https://www.sec.gov/reportspubs/investor-publications/investorpubsbegfinstmtguidehtm.html

[2] Financial Accounting Standards Board. “Accounting Standards Codification.” FASB.org.

[3] CFA Institute. “Financial Analysis Techniques.” CFA Institute Research Foundation.

[4] Damodaran, Aswath. “Debt and Value: Beyond Tax Benefits.” Stern School of Business, New York University.

[5] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Financial Ratios and Firm Performance.” FRED Economic Data.

[6] Morningstar. “Understanding Financial Statements.” Morningstar Investment Research.

[7] International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation. “IFRS Standards.” IFRS.org.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Debt to Equity Ratio

What is a good debt to equity ratio?

A “good” D/E ratio depends entirely on industry context. Technology companies should maintain D/E below 0.75, while utilities can safely operate with D/E between 1.5 and 2.0. Compare companies to industry peers rather than absolute standards. Generally, D/E below 1.0 indicates conservative financing, while D/E above 2.0 signals aggressive leverage requiring careful analysis.

How do you calculate the debt to equity ratio?

Calculate the D/E ratio by dividing total liabilities by shareholders’ equity, both found on the company’s balance sheet. The formula is: D/E Ratio = Total Liabilities ÷ Shareholders’ Equity. Ensure both figures come from the same reporting date for accuracy. The result shows how many dollars of debt exist for each dollar of equity.

What does a debt to equity ratio of 1.5 mean?

A D/E ratio of 1.5 means the company carries $1.50 in debt for every $1.00 of equity. This indicates creditors have provided 60% of the company’s financing while shareholders have provided 40%. The company uses moderate leverage that amplifies both gains and losses compared to an unleveraged company.

Is higher or lower debt to equity better?

Lower D/E ratios generally indicate less financial risk, greater stability, and more flexibility to weather economic downturns. However, very low ratios might signal underutilization of leverage that could amplify returns. The optimal ratio balances the tax benefits and return amplification of debt against bankruptcy risk and financial inflexibility. Industry context determines whether a specific ratio is appropriate.

Can the debt-to-equity ratio be negative?

Yes, when shareholders’ equity is negative (liabilities exceed assets), the D/E ratio becomes negative. This signals severe financial distress, indicating the company has accumulated losses exceeding its capital and would be insolvent if forced to liquidate immediately. Negative equity represents a major red flag for investors and often precedes bankruptcy.

Where do you find the numbers to calculate debt to equity ratio?

Find both components on the company’s balance sheet in SEC filings (10-K annual reports or 10-Q quarterly reports). Total liabilities appear approximately halfway down the balance sheet, while shareholders’ equity appears at the bottom. Financial websites like Yahoo Finance, Google Finance, and Morningstar also display pre-calculated D/E ratios, though calculating manually ensures accuracy and allows for customized variations.

How often should investors check the debt-to-equity ratio?

Review the D/E ratio quarterly when companies release earnings reports and updated balance sheets. For existing portfolio holdings, track changes each quarter to identify trends. For potential investments, examine at least three years of historical data to understand whether the current ratio represents normal operations or a temporary deviation. Significant changes (>20% in a single quarter) warrant immediate investigation.

What’s the difference between debt-to-equity and debt ratio?

The debt ratio expresses liabilities as a percentage of total assets (Total Liabilities ÷ Total Assets), while the D/E ratio compares liabilities to equity (Total Liabilities ÷ Shareholders’ Equity). Both measure leverage but from different perspectives. The debt ratio shows what percentage of assets are financed by debt, while the D/E ratio shows the relative proportion of debt to equity financing. They’re mathematically related: D/E = Debt Ratio ÷ (1 – Debt Ratio).