Most investors scan financial statements like separate snapshots—revenue here, assets there, cash somewhere else. But here’s the truth: financial statements don’t work in isolation. They’re interconnected pieces of a single financial story, each revealing how money flows through a business, where it comes from, and where it goes.

Understanding the financial statements’ relationship transforms how you evaluate companies. A profitable income statement means nothing if cash flow is negative. A strong balance sheet can hide deteriorating operations. The real insight emerges when you see how these three core statements—the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement—link together to reveal a company’s complete financial health.

This guide breaks down exactly how these statements connect, why those connections matter for investors, and how to read them as an integrated system rather than isolated reports.

Key Takeaways

- Financial statements are interconnected: Net income flows from the income statement to both the balance sheet (retained earnings) and the cash flow statement (starting point for operations)

- Profit ≠ cash: A company can show strong net income while experiencing negative cash flow due to timing differences in revenue recognition and actual cash collection

- Balance sheet changes explain cash movements: Every line item change on the balance sheet between periods affects cash flow—increases in assets use cash, while increases in liabilities provide cash

- The statements validate each other: Cross-referencing numbers across all three statements helps identify accounting irregularities, management quality, and true financial performance

- Integrated analysis reveals business quality: Understanding how statements connect helps investors distinguish between sustainable growth and accounting-driven appearances

Understanding the Three Core Financial Statements

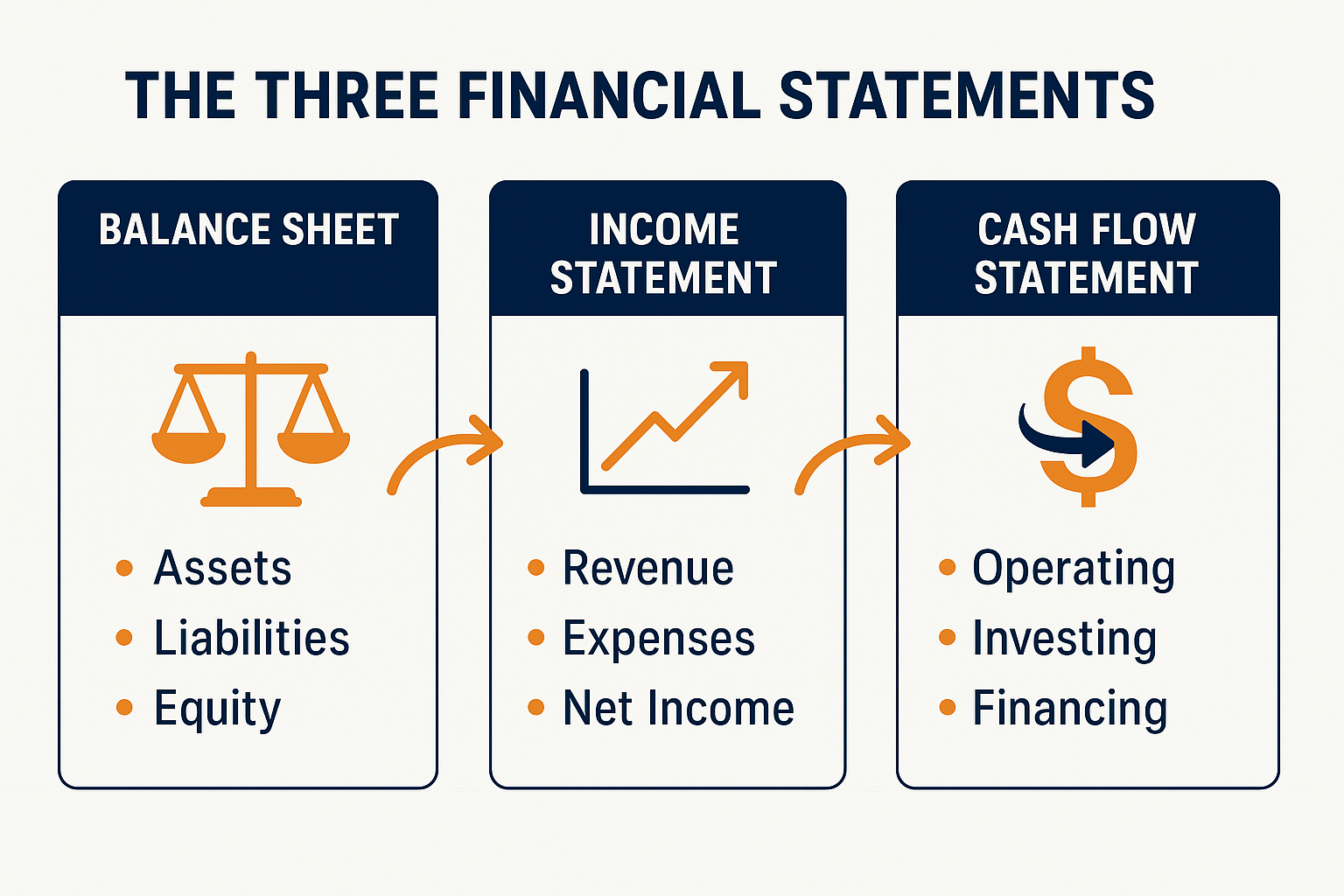

Before exploring how financial statements work together, it’s essential to understand what each statement individually measures.

The Balance Sheet: Financial Position at a Point in Time

The balance sheet captures a company’s financial position on a specific date—what it owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and what belongs to shareholders (equity). Think of it as a financial photograph taken at midnight on the last day of a reporting period.

The fundamental accounting equation governs every balance sheet:

Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity

Assets include cash, inventory, equipment, and receivables. Liabilities encompass debts, payables, and obligations. Equity represents the residual claim—what’s left after subtracting liabilities from assets.

The balance sheet answers critical questions: Does the company have enough liquid assets to cover short-term obligations? How much debt burdens the business? What’s the book value of shareholder ownership?

The Income Statement: Performance Over a Period

While the balance sheet shows position, the income statement measures performance over time—typically a quarter or a year. It follows a simple structure:

Revenue – Expenses = Net Income

The income statement starts with revenue (money earned from selling goods or services), subtracts the cost of goods sold to calculate gross profit, then deducts operating expenses, interest, and taxes to arrive at net income—the bottom line.

This statement reveals profitability: Is the company generating more money than it spends? Are profit margins expanding or contracting? How efficiently does management convert sales into earnings?

According to the CFA Institute, the income statement provides the primary measure of a company’s profitability and operating performance during a specific period.

The Cash Flow Statement: Actual Money Movement

The cash flow statement reconciles the difference between accounting profit and actual cash. It tracks every dollar that flows in and out of the business across three categories:

- Operating activities: Cash generated from core business operations

- Investing activities: Cash spent on or received from investments in assets

- Financing activities: Cash flows from debt, equity, and dividend transactions

The cash flow statement answers the most practical question: Does this company generate real cash, or just accounting profits?

Insight: A company can report positive net income while experiencing negative cash flow, and vice versa. The cash flow statement reveals this disconnect and explains its cause.

How the Financial Statements Relationship Works

The three financial statements connect through specific line items that flow from one report to another. Understanding these connections transforms isolated numbers into a coherent economic narrative.

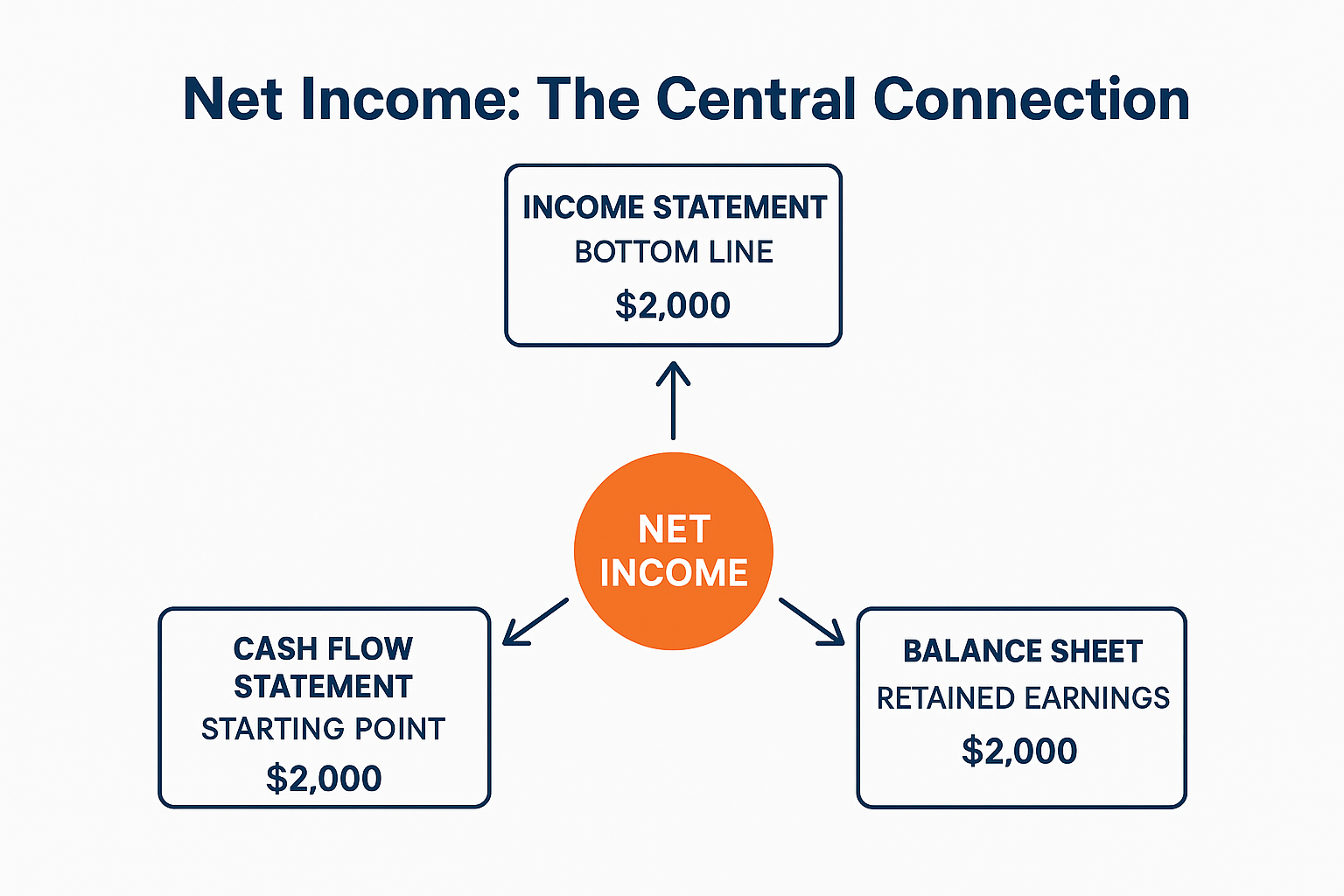

Net Income: The Primary Connection Point

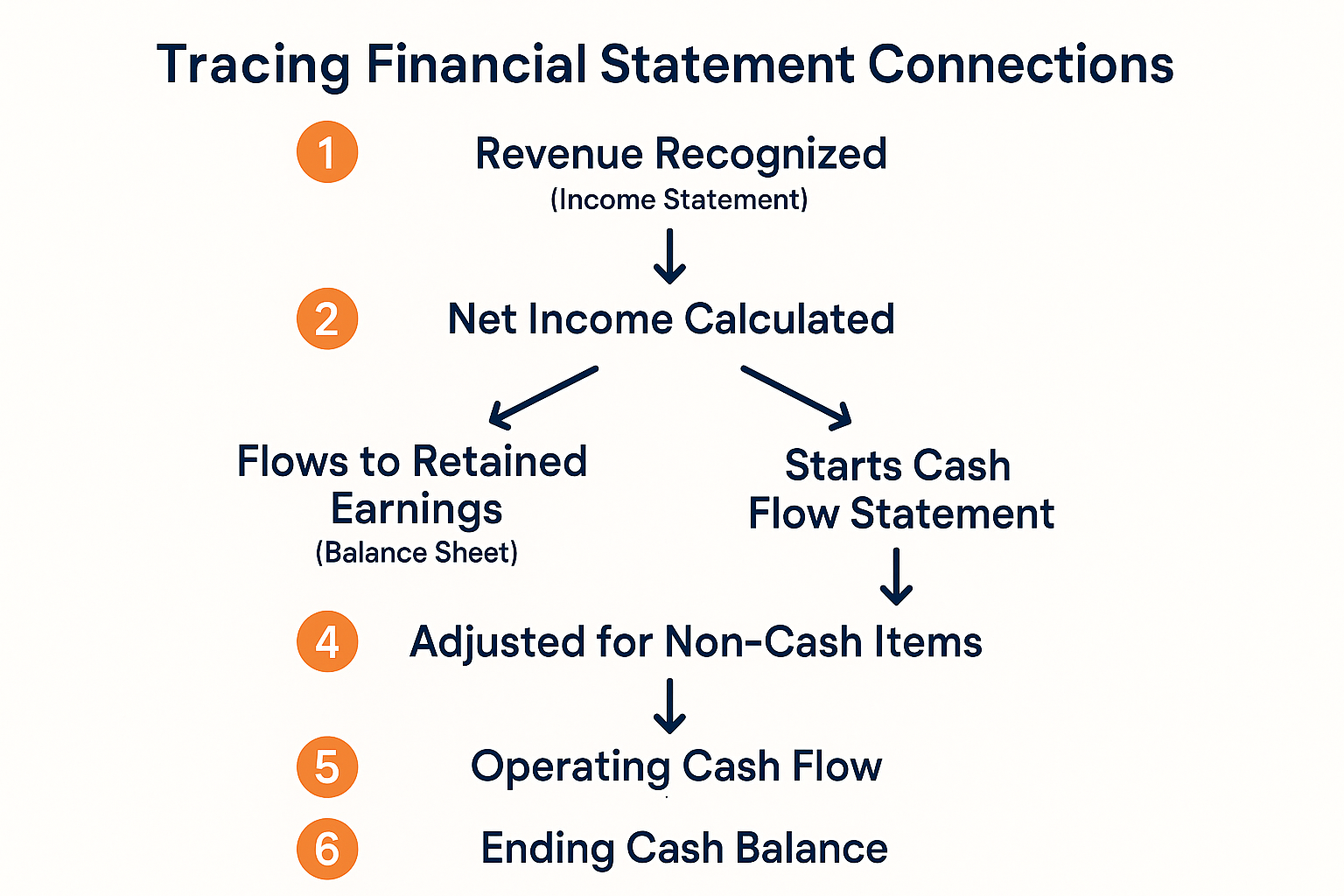

Net income serves as the central link between all three statements. Here’s how it flows:

- Income Statement → Cash Flow Statement: Net income appears as the starting point in the operating activities section of the cash flow statement

- Income Statement → Balance Sheet: Net income increases retained earnings in the shareholders’ equity section of the balance sheet

This dual connection means every dollar of profit simultaneously affects both the company’s equity position and its cash flow calculation.

From Income Statement to Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement begins with net income, then makes adjustments to convert accrual-basis accounting (how profit is measured) into cash-basis reality (how money actually moves).

Key adjustments include:

- Adding back non-cash expenses: Depreciation and amortization reduce net income but don’t involve actual cash outflows

- Adjusting for working capital changes: Changes in receivables, inventory, and payables affect cash differently than they affect accounting profit

- Removing non-operating items: Gains or losses from asset sales appear in net income but belong in investing activities

For example, if a company reports $100 million in net income and $50 million in depreciation, the cash flow statement adds back that $50 million because depreciation is a non-cash expense. The result: operating cash flow starts at $150 million before other adjustments.

From Income Statement to Balance Sheet

Net income flows directly into retained earnings, a key component of shareholders’ equity on the balance sheet. The relationship follows this formula:

Ending Retained Earnings = Beginning Retained Earnings + Net Income – Dividends

When a company earns $10 million in net income and pays $3 million in dividends, retained earnings increase by $7 million. This increase appears on the balance sheet, directly linking profitability to equity growth.

Conversely, a net loss reduces retained earnings and shrinks shareholders’ equity. Over time, persistent losses can turn equity negative—a red flag indicating the company owes more than it owns.

From Cash Flow Statement to Balance Sheet

The cash flow statement explains every change in the cash account on the balance sheet between two periods. The ending cash balance on the cash flow statement must equal the cash line item on the balance sheet for the same date.

The reconciliation works like this:

Beginning Cash + Operating Cash Flow + Investing Cash Flow + Financing Cash Flow = Ending Cash

If a company started the year with $50 million in cash, generated $30 million from operations, spent $20 million on equipment, and borrowed $10 million, the ending cash would be $70 million—exactly what appears on the year-end balance sheet.

Balance Sheet Changes Drive Cash Flow Adjustments

Every change in balance sheet accounts between periods affects cash flow. This relationship follows a simple logic:

- Increases in assets (except cash) use cash: Buying inventory, extending more credit to customers, or purchasing equipment all require cash outflows

- Decreases in assets provide cash: Collecting receivables or selling equipment generates cash inflows

- Increases in liabilities provide cash: Borrowing money or delaying payments to suppliers brings in cash

- Decreases in liabilities use cash: Paying down debt or settling payables requires cash outflows

For instance, if accounts receivable increase by $5 million, it means the company made sales but hasn’t collected the cash yet. The cash flow statement subtracts this $5 million from net income because revenue was recognized without a corresponding cash receipt.

Understanding this stock market fundamental helps investors evaluate whether growth is sustainable or merely accounting-driven.

The Complete Financial Statements Relationship: A Practical Example

Let’s trace how a single business transaction flows through all three statements to illustrate the financial statements’ relationship in action.

Scenario: A company purchases $100,000 of equipment with cash on January 1. The equipment has a 10-year useful life and is depreciated straight-line. We’ll examine the impact over the first year.

Impact on the Balance Sheet (January 1)

Assets:

- Cash decreases by $100,000

- Property, Plant & Equipment increases by $100,000

Net effect: Total assets unchanged; cash converted to a long-term asset.

Impact on the Income Statement (Year 1)

Operating Expenses:

- Depreciation expense: $10,000 ($100,000 ÷ 10 years)

Net effect: Net income decreases by $10,000 (assuming a 0% tax rate for simplicity).

Impact on the Cash Flow Statement (Year 1)

Operating Activities:

- Net income: -$10,000 (from income statement)

- Add back depreciation: +$10,000 (non-cash expense)

- Operating cash flow: $0

Investing Activities:

- Purchase of equipment: -$100,000

Net effect: Total cash flow of -$100,000, all from investing activities.

Impact on the Balance Sheet (December 31)

Assets:

- Cash: -$100,000 (from the original purchase)

- Property, Plant & Equipment: $100,000 (original cost)

- Accumulated Depreciation: -$10,000

- Net PP&E: $90,000

Equity:

- Retained Earnings: -$10,000 (from net income impact)

Net effect: Total assets decreased by $10,000; equity decreased by $10,000. The balance sheet equation remains balanced.

This example demonstrates how a single transaction creates a connected trail across all three statements. The $100,000 cash outflow appears in investing activities. The $10,000 depreciation reduces both net income and retained earnings while being added back in operating cash flow. The balance sheet reflects both the asset acquisition and the accumulated depreciation.

Why the Financial Statements Relationship Matters for Investors

Understanding how financial statements connect provides several critical advantages for investors analyzing companies.

Identifying Quality of Earnings

The relationship between net income and operating cash flow reveals earnings quality. High-quality earnings convert readily into cash. Low-quality earnings rely on aggressive accounting or unsustainable practices.

Red flags emerge when:

- Net income consistently exceeds operating cash flow

- Accounts receivable grow faster than revenue

- Inventory builds up without corresponding sales growth

- Depreciation policies seem unrealistically long

According to Morningstar research, companies with operating cash flow consistently below net income tend to underperform over time. The disconnect suggests earnings may not be sustainable.

Detecting Financial Manipulation

Integrated statement analysis helps identify accounting irregularities. Since the statements must reconcile mathematically, manipulation in one area creates inconsistencies elsewhere.

For example, if a company inflates revenue by recognizing sales prematurely, accounts receivable will balloon relative to sales. The cash flow statement will show the disconnect—revenue appears on the income statement, but cash isn’t collected. The balance sheet reveals the growing receivables.

The SEC frequently investigates companies with persistent mismatches between reported profits and actual cash generation.

Evaluating Capital Allocation Efficiency

The interplay between statements reveals how effectively management deploys capital. Does the company reinvest cash flow productively? Are acquisitions funded with debt or equity? How much cash returns to shareholders through dividends and buybacks?

Analyzing dividend investing opportunities requires understanding how companies generate cash, allocate it across operations and investments, and distribute excess to shareholders—all visible through integrated statement analysis.

Understanding Growth Sustainability

Rapid growth often requires substantial working capital investment. The financial statements relationship shows whether growth is self-funding or requires external financing.

Sustainable growth characteristics:

- Operating cash flow funds most capital expenditures

- Working capital needs grow proportionally to revenue

- Debt levels remain manageable relative to cash generation

Unsustainable growth indicators:

- Operating cash flow lags far behind net income

- Inventory and receivables balloon faster than sales

- Increasing reliance on debt or equity issuance to fund operations

Understanding what moves the stock market includes recognizing when growth stories are backed by solid cash generation versus accounting optimism.

Common Disconnects Between Financial Statements

Several normal business situations create temporary disconnects between profitability and cash flow. Recognizing these patterns prevents misinterpretation.

Revenue Recognition vs. Cash Collection

Under accrual accounting, companies recognize revenue when earned, not when cash is received. A sale made on credit increases revenue and net income immediately, but doesn’t affect cash until the customer pays.

Impact on statements:

- Income Statement: Revenue and net income increase

- Balance Sheet: Accounts receivable increase

- Cash Flow Statement: Operating cash flow adjusted downward for the receivable increase

This timing difference is normal, but persistent growth in receivables relative to sales suggests collection problems.

Capital Expenditures vs Depreciation

When a company purchases long-lived assets, the full cash outflow occurs immediately, but the expense is spread over the asset’s useful life through depreciation.

Impact on statements:

- Cash Flow Statement: Full cash outflow in investing activities

- Income Statement: Only annual depreciation expense (much smaller)

- Balance Sheet: Asset recorded at cost; accumulated depreciation increases annually

Capital-intensive businesses like utilities or manufacturers often show positive net income but negative free cash flow (operating cash flow minus capital expenditures) during growth phases.

Stock-Based Compensation

Companies frequently compensate employees with stock options or restricted stock units. This creates an expense without a cash outflow.

Impact on statements:

- Income Statement: Compensation expense reduces net income

- Cash Flow Statement: Expense added back in operating activities (non-cash)

- Balance Sheet: Equity increases as shares are issued

Investors should monitor whether stock-based compensation dilutes ownership faster than earnings grow—a sign of value destruction despite reported profits.

Debt Issuance and Repayment

Borrowing money or repaying debt affects cash and liabilities but doesn’t touch the income statement directly.

Impact on statements:

- Cash Flow Statement: Cash inflow from borrowing (financing activities) or outflow from repayment

- Balance Sheet: Cash and debt both change

- Income Statement: Only interest expense appears, not principal payments

This distinction matters when evaluating high dividend stocks—companies borrowing to fund dividends may appear shareholder-friendly while actually increasing financial risk.

How to Analyze Financial Statements as an Integrated System

Effective financial analysis requires reading all three statements together, not sequentially. Here’s a systematic approach.

Step 1: Start with the Cash Flow Statement

Begin with the cash flow statement to understand the company’s cash generation reality. Focus on:

- Operating cash flow: Is it positive and growing?

- Free cash flow: Operating cash flow minus capital expenditures—the true cash available for discretionary use

- Cash flow trends: Are they improving or deteriorating relative to net income?

This foundation prevents being misled by accounting profits that don’t translate to actual cash.

Step 2: Compare Net Income to Operating Cash Flow

Calculate the cash flow to net income ratio:

Cash Flow Ratio = Operating Cash Flow ÷ Net Income

- Ratio > 1.0: Company converts earnings to cash efficiently; high earnings quality

- Ratio < 1.0: Earnings may include non-cash items or aggressive accounting; investigate further

- Persistent ratio < 0.8: Red flag suggesting potential earnings manipulation or deteriorating business fundamentals

Step 3: Analyze Balance Sheet Changes

Review how key balance sheet accounts changed between periods:

- Working capital: Are receivables, inventory, and payables growing faster or slower than revenue?

- Debt levels: Is leverage increasing or decreasing?

- Equity: Is it growing from retained earnings (good) or dilutive stock issuance (potentially concerning)?

These changes explain the adjustments in the cash flow statement’s operating activities section.

Step 4: Trace Connections Across Statements

Verify that key numbers reconcile:

- Net income from the income statement matches the starting point in operating cash flow

- Net income minus dividends equals the change in retained earnings on the balance sheet

- The change in cash on the balance sheet equals the net cash flow on the cash flow statement

Inconsistencies may indicate errors, restatements, or accounting irregularities.

Step 5: Calculate Integrated Financial Ratios

Some of the most powerful financial ratios require data from multiple statements:

Return on Equity (ROE) = Net Income ÷ Shareholders’ Equity

- Combines the income statement (numerator) and the balance sheet (denominator)

Free Cash Flow Yield = Free Cash Flow ÷ Market Capitalization

- Uses cash flow statement and market data

Debt-to-EBITDA = Total Debt ÷ EBITDA

- Combines balance sheet debt with income statement earnings

These ratios reveal relationships invisible when viewing statements in isolation.

Understanding these metrics helps when evaluating market volatility and determining which companies have the financial strength to weather economic uncertainty.

Real-World Application: Evaluating Two Companies

Let’s compare two hypothetical companies to demonstrate how the financial statements’ relationship reveals different business qualities.

Company A: High-Quality Earnings

Income Statement:

- Revenue: $500 million

- Net Income: $50 million

- Net margin: 10%

Cash Flow Statement:

- Operating Cash Flow: $60 million

- Capital Expenditures: $20 million

- Free Cash Flow: $40 million

Balance Sheet Changes:

- Accounts Receivable: Increased 8% (in line with revenue growth)

- Inventory: Increased 7% (in line with revenue growth)

- Debt: Decreased $10 million

Analysis: Company A shows excellent earnings quality. Operating cash flow exceeds net income, suggesting conservative accounting. Working capital grows proportionally to sales. The company generates enough free cash flow to fund operations, invest in growth, and reduce debt. This is a financially healthy business.

Company B: Questionable Earnings Quality

Income Statement:

- Revenue: $500 million

- Net Income: $50 million

- Net margin: 10%

Cash Flow Statement:

- Operating Cash Flow: $30 million

- Capital Expenditures: $25 million

- Free Cash Flow: $5 million

Balance Sheet Changes:

- Accounts Receivable: Increased 25% (much faster than revenue)

- Inventory: Increased 30% (much faster than revenue)

- Debt: Increased $20 million

Analysis: Company B shows concerning patterns. Operating cash flow significantly lags net income. Receivables and inventory balloon faster than sales, suggesting potential collection problems or excess unsold goods. Free cash flow barely covers dividends. The company borrowed $20 million despite reporting $50 million in profit. These red flags warrant deeper investigation.

Both companies report identical net income and margins, but the financial statements’ relationship reveals vastly different underlying business quality.

Advanced Concepts: Non-Cash Items and Reconciliations

Several sophisticated accounting concepts affect how statements connect. Understanding these nuances improves analytical precision.

Deferred Taxes

Differences between tax accounting and financial reporting create deferred tax assets and liabilities. These appear on the balance sheet and create adjustments in the cash flow statement.

Example: A company uses accelerated depreciation for tax purposes (reducing current taxes) but straight-line depreciation for financial reporting (showing higher net income). This creates a deferred tax liability—taxes owed in the future when the timing differences reverse.

Goodwill and Intangible Assets

Acquisitions often create goodwill—the premium paid above the fair value of identifiable assets. Goodwill appears on the balance sheet but doesn’t amortize under current accounting rules. However, impairment charges reduce goodwill and flow through the income statement.

Impact on statements:

- Balance Sheet: Goodwill decreases

- Income Statement: Impairment charge reduces net income

- Cash Flow Statement: Impairment added back (non-cash charge)

Large impairments signal overpayment for acquisitions—a management quality concern.

Foreign Currency Translation

Multinational companies must translate foreign subsidiary financials into their reporting currency. Exchange rate fluctuations create gains or losses that appear in equity (accumulated other comprehensive income) rather than net income.

These adjustments affect the balance sheet without flowing through the income statement, creating another layer of complexity in the financial statements’ relationship.

Common Mistakes When Analyzing Financial Statements

Even experienced investors make errors when examining financial statements. Avoiding these pitfalls improves analysis quality.

Mistake 1: Ignoring the Cash Flow Statement

Many investors focus exclusively on the income statement, assuming profitability equals cash generation. This oversight misses companies burning cash despite reporting profits.

Solution: Always review operating cash flow alongside net income. Persistent divergence requires investigation.

Mistake 2: Confusing Cash Flow with Free Cash Flow

Operating cash flow measures cash from operations. Free cash flow subtracts necessary capital expenditures—the cash truly available for discretionary use.

Solution: Calculate free cash flow (operating cash flow minus capex) to assess true cash generation available for dividends, buybacks, or debt reduction.

Mistake 3: Overlooking Working Capital Changes

Rapid growth often requires substantial working capital investment. Companies may report strong profits while consuming cash to fund receivables and inventory.

Solution: Monitor working capital trends relative to revenue growth. Disproportionate increases signal potential problems.

Mistake 4: Missing One-Time Items

Non-recurring gains, restructuring charges, or asset sales can distort both net income and cash flow in a single period.

Solution: Adjust for one-time items to assess ongoing operational performance. Focus on normalized earnings and sustainable cash generation.

Mistake 5: Ignoring Footnotes and MD&A

The financial statement footnotes and Management Discussion & Analysis sections provide context for the numbers—accounting policy choices, contingencies, and management’s perspective.

Solution: Read footnotes for significant accounting policies, especially revenue recognition, depreciation methods, and inventory valuation. The MD&A often reveals trends not obvious in the numbers alone.

Financial Statements Relationship in Different Industries

The interplay between financial statements varies by industry due to different business models and capital requirements.

Technology and Software Companies

Software businesses often show:

- High gross margins (80%+)

- Significant stock-based compensation (creating divergence between net income and cash flow)

- Minimal capital expenditures

- Deferred revenue (cash collected before revenue recognized)

The balance sheet often shows large deferred revenue balances from subscription models. Cash flow exceeds net income due to this favorable timing—customers pay upfront, but revenue is recognized ratably over the subscription period.

Manufacturing and Industrial Companies

Manufacturers typically display:

- Lower margins (20-40%)

- High capital expenditure requirements

- Significant inventory and receivables

- Depreciation as a major expense

Free cash flow often lags net income due to heavy capex needs. The balance sheet carries substantial property, plant, and equipment. Working capital management significantly impacts cash flow.

Retail Companies

Retailers generally show:

- Moderate margins (5-15%)

- High inventory turnover

- Seasonal working capital fluctuations

- Lease obligations (operating leases are now on the balance sheet under current accounting standards)

The financial statements’ relationship in retail reveals inventory management efficiency. Companies with faster inventory turns generate cash more efficiently. Seasonal businesses show dramatic working capital swings between quarters.

Financial Services

Banks and financial institutions have unique statement structures:

- Assets primarily consist of loans and securities

- Liabilities include customer deposits

- Net interest margin drives profitability

- Loan loss provisions affect both income and the balance sheet

The traditional cash flow statement is less relevant for banks. Instead, focus on net interest income, credit quality metrics, and capital adequacy ratios.

Understanding these industry variations helps when researching smart moves for portfolio construction across different sectors.

Tools and Resources for Financial Statement Analysis

Several resources help investors access and analyze financial statements effectively.

SEC EDGAR Database

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s EDGAR system provides free access to all public company filings, including:

- 10-K: Annual report with complete audited financial statements

- 10-Q: Quarterly report with unaudited statements

- 8-K: Current reports for material events

All U.S. public companies must file these documents, making EDGAR the authoritative source for financial data.

Financial Data Platforms

Several platforms aggregate and standardize financial statement data:

- Morningstar: Provides 10 years of standardized financial data with analytical tools

- Bloomberg Terminal: Professional-grade data and analysis (subscription required)

- Yahoo Finance: Free access to basic financial statements and key metrics

- Seeking Alpha: Financial data plus community analysis

These platforms simplify comparing companies across periods and industries.

Spreadsheet Analysis

Building custom spreadsheet models allows deep analysis of the financial statements relationship. Download historical data and create:

- Trend analysis: Track key metrics across multiple years

- Common-size statements: Express line items as percentages to identify patterns

- Ratio calculations: Compute integrated ratios from multiple statements

- Cash flow reconciliations: Verify statement connections

Spreadsheet modeling develops a deeper understanding than passive data consumption.

The Role of Financial Statements in Investment Decisions

Understanding the financial statements’ relationship directly improves investment outcomes through better company evaluation.

Fundamental Analysis Foundation

The three financial statements provide the raw material for fundamental analysis—evaluating a company’s intrinsic value based on financial performance and position.

Key valuation inputs derived from statements:

- Earnings: From the income statement (P/E ratio)

- Book value: From the balance sheet (P/B ratio)

- Cash flow: From the cash flow statement (P/CF ratio)

- Free cash flow: For discounted cash flow models

Investors who understand how these statements connect can better assess whether market prices reflect underlying business value.

Risk Assessment

The financial statements’ relationship reveals financial risks:

- Liquidity risk: Can the company meet short-term obligations? (Balance sheet current ratio)

- Solvency risk: Can the company service long-term debt? (Debt-to-equity, interest coverage)

- Operational risk: Are operations generating cash? (Operating cash flow trends)

Companies with strong balance sheets and consistent cash generation weather economic downturns better than leveraged businesses with questionable earnings quality.

This analysis proves particularly valuable when evaluating why the stock market goes up over time—companies with solid fundamentals drive long-term market returns.

Portfolio Construction

Understanding financial statement integration helps build diversified portfolios:

- Growth investing: Focus on revenue and earnings growth, but verify with cash flow

- Value investing: Identify undervalued companies with strong balance sheets

- Income investing: Select companies with sustainable free cash flow to support dividends

- Quality investing: Target businesses with high returns on equity and consistent cash conversion

Different investment styles emphasize different statement elements, but all benefit from integrated analysis.

Financial Statements Connection Visualizer

See how the three financial statements connect in real-time

Conclusion

The financial statements relationship transforms isolated accounting reports into a powerful analytical framework. The balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement don’t exist independently—they’re interconnected components of a single financial story, each revealing different dimensions of business performance.

Net income connects all three statements, flowing from the income statement to both retained earnings on the balance sheet and the starting point of the cash flow statement. Every change in balance sheet accounts between periods affects cash flow, explaining why accounting profit often diverges from actual cash generation. Understanding these connections reveals earnings quality, identifies potential manipulation, and distinguishes sustainable growth from accounting illusions.

Actionable next steps:

- Download financial statements for a company you own or are considering—access them free through the SEC EDGAR database

- Trace net income from the income statement to the cash flow statement and balance sheet retained earnings to verify the connections

- Calculate the cash flow to net income ratio to assess earnings quality—ratios consistently above 1.0 indicate high-quality earnings

- Review working capital changes on the balance sheet and verify they match the adjustments in the operating cash flow section

- Compute free cash flow by subtracting capital expenditures from operating cash flow to determine true discretionary cash generation

The math behind money reveals itself most clearly when you understand how financial statements work together. Companies that consistently convert profits to cash, maintain healthy balance sheets, and generate sustainable free cash flow create long-term shareholder value. Those that show persistent disconnects between reported earnings and actual cash generation often disappoint investors over time.

Master the financial statements relationship, and you’ll see beyond accounting presentations to the underlying economic reality—the foundation of successful long-term investing.

About the Author

Written by Max Fonji, founder of TheRichGuyMath.com—a finance educator and investor who explains the “math behind money” in simple, actionable terms. With experience in investment strategy, personal finance, and wealth-building systems, Max helps readers understand how financial decisions create lasting results. Connect with Max and explore more financial insights at The Rich Guy Math.

Disclaimer

Disclaimer: The content on TheRichGuyMath.com is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial or investment advice. Financial statements are complex documents that require careful analysis, and this article provides general education rather than specific investment recommendations. Always consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Past performance indicated in examples does not guarantee future results. All investors should conduct their own due diligence and consider their individual financial circumstances, risk tolerance, and investment objectives.

FAQ: Financial Statements Relationship

What is the financial statements relationship?

The financial statements relationship describes how the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement interconnect through specific line items. Net income from the income statement flows to both retained earnings on the balance sheet and serves as the starting point for the cash flow statement. Changes in balance sheet accounts between periods explain adjustments in the cash flow statement. Together, these connections ensure the statements tell a consistent financial story.

Why does the financial statements relationship matter for investors?

Understanding how financial statements connect helps investors identify earnings quality, detect potential accounting manipulation, evaluate capital allocation efficiency, and assess growth sustainability. Companies can report positive net income while burning cash, or vice versa. The relationship between profit and cash flow, combined with balance sheet changes, reveals whether reported earnings translate to real economic value or merely reflect aggressive accounting choices.

How can someone apply the financial statements relationship concept?

Start by comparing operating cash flow to net income — a ratio above 1.0 indicates high earnings quality. Next, review how working capital accounts (receivables, inventory, payables) changed on the balance sheet and verify these changes match the adjustments in the cash flow statement’s operating section. Finally, trace net income from the income statement to retained earnings on the balance sheet and the cash flow statement starting point. This integrated approach reveals business quality invisible when viewing statements in isolation.

What’s the difference between net income and cash flow?

Net income measures accounting profit using accrual accounting — revenue recognized when earned, expenses when incurred, regardless of cash timing. Cash flow measures actual money movement. A company can report net income by making credit sales while cash isn’t collected until later, creating positive income but neutral or negative cash flow. Conversely, collecting old receivables generates cash without affecting current net income.

Can a profitable company have negative cash flow?

Yes. Companies experiencing rapid growth often show positive net income but negative cash flow because they must invest heavily in working capital (inventory, receivables) and capital expenditures to support expansion. The income statement recognizes revenue from credit sales immediately, while the cash flow statement reflects that cash hasn’t been collected yet. This pattern is normal during growth phases but becomes concerning if it persists without corresponding revenue increases.