Imagine two retirees who both saved $1 million and earned identical average returns of 6% annually. One retires in 2008, right before the market crash. The other retired in 2012, after the recovery.

Twenty years later, one has completely run out of money. The other still has over $600,000 remaining.

Same starting balance. Same average return. Same withdrawal rate. Completely different outcomes.

This isn’t a hypothetical scenario; it’s the devastating reality of Sequence of Returns Risk, one of the most underestimated threats to retirement security. While most investors focus obsessively on average returns, the math behind money reveals a more uncomfortable truth: when you earn those returns matters just as much as what you earn.

Understanding the sequence of returns risk is essential for anyone approaching or entering retirement. This comprehensive guide breaks down the data-driven insights, real-world case studies, and evidence-based strategies that can protect your retirement portfolio from this hidden danger.

Key Takeaways

- Sequence of Returns Risk refers to the danger of experiencing negative investment returns early in retirement when withdrawing funds, which can permanently damage portfolio longevity

- The order of returns matters more than the average return during the withdrawal phase; bad early years can deplete your portfolio beyond recovery

- A retiree experiencing poor returns in the first 5-10 years can run out of money decades sooner than someone with identical average returns but better timing

- Multiple evidence-based strategies can mitigate this risk: bucket strategies, dynamic withdrawal rules, bond tents, diversification, and partial annuitization

- Pre-retirees should assess their sequence risk exposure 5-10 years before retirement and implement protective measures before leaving the workforce

What Is Sequence of Returns Risk?

Sequence of Returns Risk is the danger that the timing and order of investment returns will negatively impact a portfolio’s longevity when regular withdrawals are being made.

In plain English: experiencing market downturns early in retirement, when you’re selling assets to fund living expenses, can irreversibly damage your financial security, even if markets eventually recover.

This risk exists because of a fundamental mathematical principle: withdrawing money from a declining portfolio creates a compounding negative effect that cannot be undone by future gains. Each withdrawal during a downturn forces you to sell more shares at depressed prices, permanently reducing the number of shares available to participate in future market recoveries.

The concept was first rigorously analyzed by financial planner William Bengen in his landmark 1994 study that introduced the 4% rule, a withdrawal strategy designed specifically to address sequence risk.

Why Sequence of Returns Risk Matters Most Near Retirement

Sequence of Returns Risk becomes critical during two specific life phases:

- The five years before retirement (when portfolios are at their largest)

- The first 10-15 years of retirement (when withdrawal patterns are established)

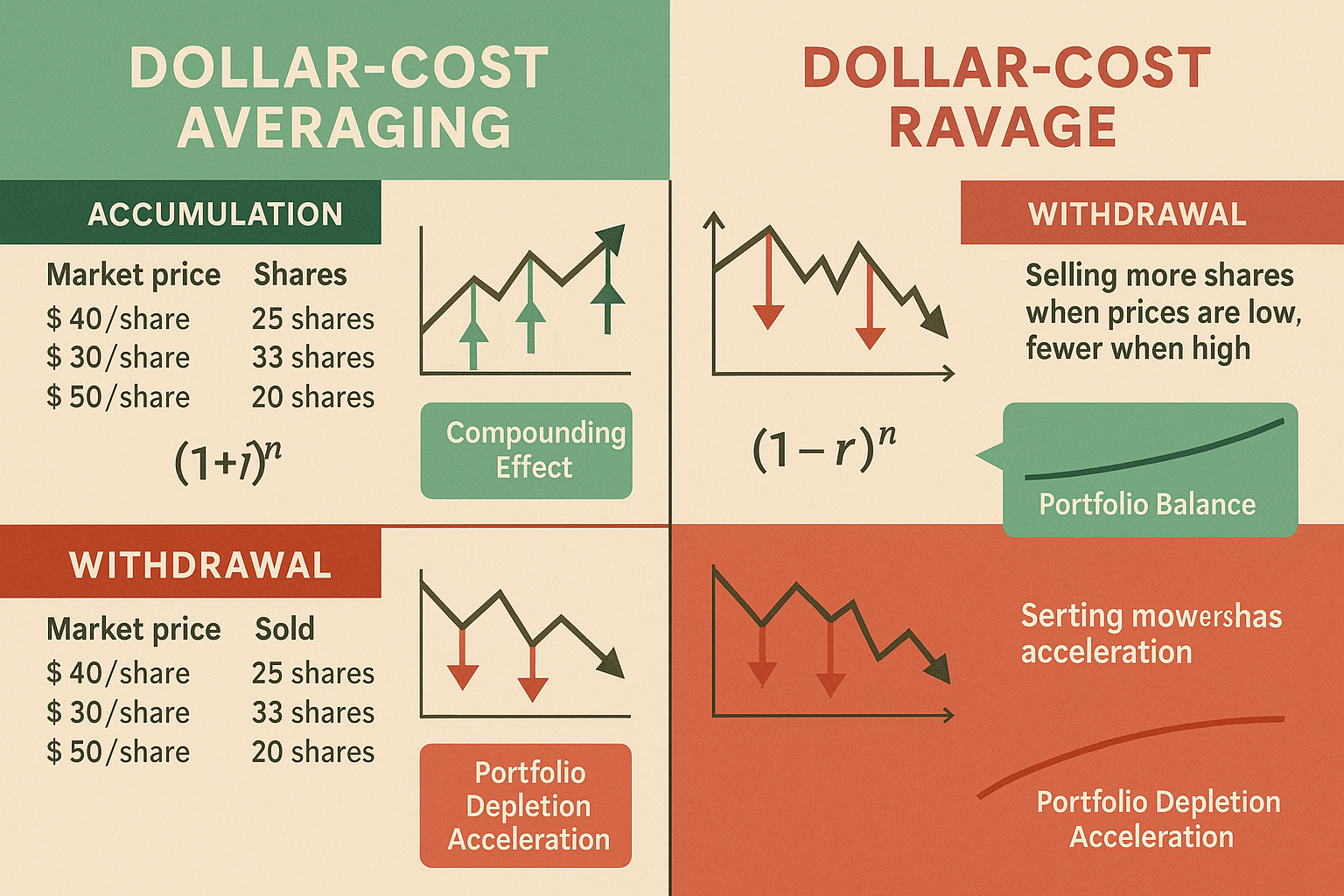

During accumulation, when you’re still working and contributing to your portfolio, sequence risk is negligible. Poor early returns are actually beneficial because you’re buying more shares at lower prices through dollar-cost averaging. Market volatility works in your favor.

But the moment you switch from contributing to withdrawing, the math reverses. Now, volatility works against you through what researchers call “dollar-cost averaging” or “reverse dollar-cost averaging”.

This phase-dependent nature makes sequence risk particularly insidious: investors spend decades correctly believing that market timing doesn’t matter, only to discover that timing suddenly matters enormously the moment they retire.

How the Sequence of Returns Risk Works

The mechanics of Sequence of Returns Risk center on a counterintuitive mathematical reality: the order of returns fundamentally changes outcomes when money is being withdrawn.

Order of Returns vs Average Return

Consider three hypothetical 10-year investment scenarios, each with the same $500,000 starting balance and no withdrawals:

Scenario A: Returns of -20%, -10%, 5%, 8%, 12%, 15%, 18%, 10%, 7%, 5% (average: 5%)

Scenario B: Returns of 5%, 7%, 10%, 18%, 15%, 12%, 8%, 5%, -10%, -20% (average: 5%)

Scenario C: Returns of 5%, 5%, 5%, 5%, 5%, 5%, 5%, 5%, 5%, 5% (average: 5%)

Without withdrawals, all three scenarios end with approximately the same balance: around $814,000. The sequence doesn’t matter during accumulation because you’re not selling assets.

But add annual withdrawals of $30,000 (a 6% initial withdrawal rate), and the outcomes diverge dramatically:

- Scenario A (bad returns early): Final balance approximately $312,000

- Scenario B (bad returns late): Final balance approximately $687,000

- Scenario C (consistent returns): Final balance approximately $521,000

Same average return. Radically different outcomes. This is the Sequence of Returns Risk in action.

The Mathematical Mechanism

The destruction occurs through a three-step process:

Step 1: Market decline reduces portfolio value

Step 2: Fixed-dollar withdrawal requires selling a larger percentage of the now-smaller portfolio

Step 3: Fewer remaining shares participate in the eventual market recovery

This creates a permanent loss of compounding capacity that future gains cannot restore. As a result, portfolio longevity depends not just on average returns, but on the specific sequence in which those returns occur.

Understanding compound interest helps explain why this matters; compounding works powerfully in both directions, amplifying both gains and losses when withdrawals are involved.

Example: Same Average Return, Very Different Outcomes

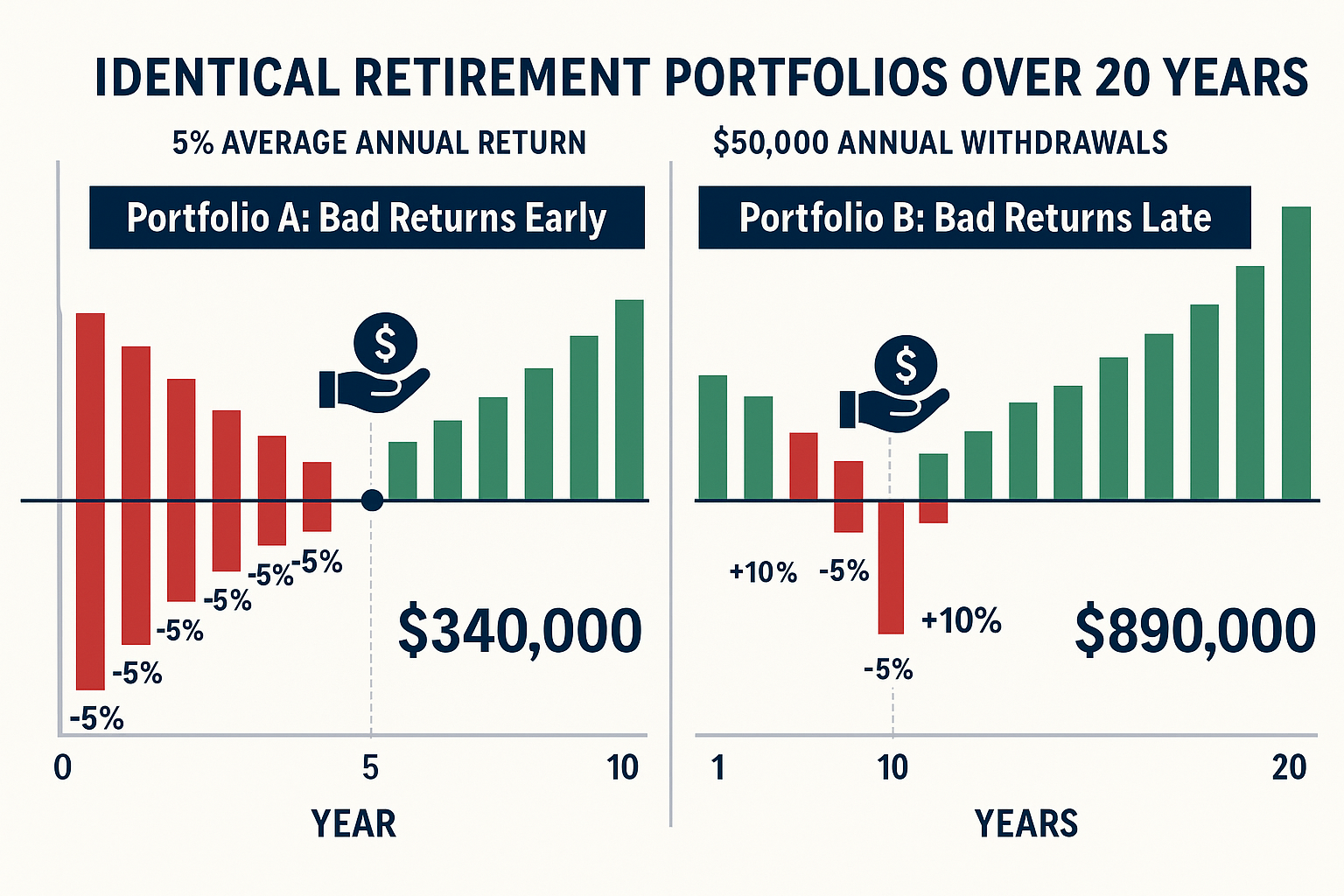

Let’s examine two retirees with identical portfolios to illustrate how Sequence of Returns Risk creates divergent retirement outcomes.

The Setup

Both retirees:

- Start with $1,000,000 at age 65

- Withdraw $50,000 annually (5% initial withdrawal rate)

- Experience the same 10 annual returns: 25%, 15%, 5%, -5%, -15%, -15%, -5%, 5%, 15%, 25%

- Achieve an identical 5% average annual return over the decade

The only difference: the order in which they experience these returns.

Portfolio A: Bad Returns Early (2008 Retiree)

| Year | Return | Beginning Balance | Withdrawal | Ending Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -15% | $1,000,000 | $50,000 | $807,500 |

| 2 | -15% | $807,500 | $50,000 | $636,375 |

| 3 | -5% | $636,375 | $50,000 | $557,056 |

| 4 | -5% | $557,056 | $50,000 | $479,203 |

| 5 | 5% | $479,203 | $50,000 | $453,163 |

| 6 | 5% | $453,163 | $50,000 | $425,821 |

| 7 | 15% | $425,821 | $50,000 | $439,695 |

| 8 | 15% | $439,695 | $50,000 | $455,649 |

| 9 | 25% | $455,649 | $50,000 | $506,561 |

| 10 | 25% | $506,561 | $50,000 | $583,201 |

Final balance after 10 years: $583,201

Portfolio B: Bad Returns Late (2012 Retiree)

| Year | Return | Beginning Balance | Withdrawal | Ending Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25% | $1,000,000 | $50,000 | $1,187,500 |

| 2 | 25% | $1,187,500 | $50,000 | $1,434,375 |

| 3 | 15% | $1,434,375 | $50,000 | $1,599,531 |

| 4 | 15% | $1,599,531 | $50,000 | $1,789,461 |

| 5 | 5% | $1,789,461 | $50,000 | $1,825,934 |

| 6 | 5% | $1,825,934 | $50,000 | $1,867,231 |

| 7 | -5% | $1,867,231 | $50,000 | $1,723,869 |

| 8 | -5% | $1,723,869 | $50,000 | $1,587,676 |

| 9 | -15% | $1,587,676 | $50,000 | $1,299,524 |

| 10 | -15% | $1,299,524 | $50,000 | $1,054,595 |

Final balance after 10 years: $1,054,595

The Devastating Gap

Portfolio B has 81% more wealth than Portfolio A after just 10 years ($1,054,595 vs. $583,201), despite identical average returns and withdrawal amounts.

If we extend this simulation to 30 years with more realistic variable returns, Portfolio A runs out of money around year 22, while Portfolio B still has over $400,000 remaining, enough to last another decade or more.

This dramatic difference exists purely because of the sequence in which returns occurred. Portfolio A’s retiree experienced the mathematical nightmare of Sequence of Returns Risk, which is characterized by negative returns when the portfolio is at its largest and most vulnerable.

Why This Risk Is Worst During Withdrawals

The danger of Sequence of Returns Risk exists exclusively during the withdrawal phase of investing. Understanding why requires examining the fundamental difference between accumulation and decumulation.

Accumulation vs. Decumulation: The Mathematical Reversal

During accumulation (working years when you’re contributing):

- Market declines allow you to purchase more shares at lower prices

- Volatility becomes an advantage through dollar-cost averaging

- Time is on your side; you can wait for recovery

- Early poor returns are actually beneficial for long-term wealth building

During decumulation (retirement when you’re withdrawing):

- Market declines force you to sell more shares to meet withdrawal needs

- Volatility becomes a liability through dollar-cost ravage

- Time works against you; each year of withdrawals reduces recovery potential

- Early poor returns create permanent portfolio damage

This reversal represents one of the most important transitions in personal finance, yet many retirees fail to adjust their strategy accordingly. The investing fundamentals that served them well during accumulation can become dangerous during retirement.

Dollar-Cost Ravage Explained

Dollar-cost averaging (also called reverse dollar-cost averaging) is the destructive mirror image of dollar-cost averaging.

When markets decline during retirement:

- Your portfolio value drops (say, from $1,000,000 to $800,000)

- Your fixed-dollar withdrawal remains constant ($50,000)

- You must now sell 6.25% of your portfolio instead of 5%

- This larger percentage withdrawal leaves fewer shares to participate in recovery

- When markets eventually rebound, you will have permanently fewer shares benefiting from growth

Each withdrawal during a downturn “locks in” losses by converting temporary market declines into permanent reductions in share count. Future market gains cannot restore shares that have been sold; they can only grow the remaining shares.

This mathematical reality makes the first decade of retirement the most critical period for portfolio survival. Research by financial planning expert Michael Kitces shows that portfolio outcomes are primarily determined by returns in the first 10 years of retirement, with later returns having a diminishing impact.

Why Recovery Doesn’t Fix the Problem

Many retirees mistakenly believe that “the market always comes back” will protect them. While markets do historically recover, individual portfolios experiencing withdrawals may not.

Consider a retiree who loses 40% in year one (like 2008) and then withdraws 5%:

- Starting balance: $1,000,000

- After 40% loss: $600,000

- After $50,000 withdrawal: $550,000

- Shares sold: Significantly more than planned

Even if the market fully recovers with a 67% gain (required to restore a 40% loss), the portfolio only grows to approximately $918,500, still below the starting value, and that’s before the second year’s withdrawal.

The retiree has permanently lost ground, not because markets failed to recover, but because withdrawals during the decline reduced the capital available to participate in that recovery.

The Math Behind Sequence of Returns Risk

Understanding the mathematical foundation of Sequence of Returns Risk provides clarity on why this phenomenon is so destructive and why traditional metrics like average returns become misleading during retirement.

The Portfolio Withdrawal Formula

The basic formula for portfolio value after withdrawals is:

Ending Balance = (Beginning Balance × (1 + Return)) – Withdrawal

Applied sequentially over multiple years, this becomes:

Balance_n = ((Balance_0 × (1 + R_1) – W) × (1 + R_2) – W) × (1 + R_3) – W)…

Where:

- Balance_n = portfolio value after n years

- Balance_0 = initial portfolio value

- R_n = return in year n

- W = annual withdrawal amount

This formula reveals why sequence matters: returns are multiplied against different base amounts depending on when they occur. Early negative returns reduce the base for all future calculations, while early positive returns increase it.

Geometric vs Arithmetic Returns

Sequence of Returns Risk also highlights the critical difference between arithmetic (simple average) and geometric (compound) returns.

Arithmetic return = Sum of all returns ÷ Number of periods

Geometric return = [(1 + R_1) × (1 + R_2) × … × (1 + R_n)]^(1/n) – 1

Without withdrawals, geometric returns determine actual portfolio growth. With withdrawals, even geometric returns become insufficient predictors because the base changes with each withdrawal.

Example:

- Year 1: -50% return

- Year 2: +100% return

- Arithmetic average: 25%

- Geometric average: 0%

Starting with $100,000 and no withdrawals, you end with $100,000 (geometric return correctly predicts outcome).

Starting with $100,000, withdrawing $10,000 annually:

- After Year 1: ($100,000 × 0.5) – $10,000 = $40,000

- After Year 2: ($40,000 × 2.0) – $10,000 = $70,000

You’ve lost 30% despite a 0% geometric return and a 25% arithmetic return. This is sequence risk in mathematical form.

Volatility Drag During Withdrawals

Volatility drag (also called variance drag) refers to the mathematical reality that higher volatility reduces compound returns. This effect amplifies dramatically when withdrawals are involved.

The approximate impact of volatility drag is:

Geometric Return ≈ Arithmetic Return – (Variance ÷ 2)

During retirement, add withdrawal drag:

Effective Return ≈ Arithmetic Return – (Variance ÷ 2) – Withdrawal Rate

This formula demonstrates why retirees need to focus on risk management and volatility reduction, not just return maximization. A portfolio with 8% average returns and high volatility may produce worse retirement outcomes than a portfolio with 6% returns and low volatility.

Understanding these mathematical principles connects to broader risk management strategies essential for wealth preservation during retirement.

How to Reduce Sequence of Returns Risk

Fortunately, Sequence of Returns Risk can be substantially mitigated through evidence-based strategies. No single approach eliminates the risk, but combining multiple techniques creates robust protection.

Diversification

Diversification reduces sequence risk by smoothing returns across multiple asset classes, reducing the probability of severe concentrated losses early in retirement.

How it works:

- Allocate across stocks, bonds, real estate, and cash equivalents

- Include both domestic and international exposure

- Diversify within asset classes (large-cap, small-cap, value, growth)

- Consider alternative investments with low correlation to stocks

Why it helps:

When one asset class experiences severe declines, others may remain stable or even gain value, reducing the magnitude of portfolio drawdowns during critical early retirement years.

Implementation:

A classic diversified retirement portfolio might include:

- 40% U.S. stocks (via index funds)

- 20% international stocks

- 30% bonds (mix of government and corporate)

- 10% cash and alternatives

Research by Vanguard demonstrates that a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio historically experiences approximately 30% smaller maximum drawdowns than a 100% stock portfolio, significantly reducing sequence risk exposure.

Proper diversification strategies should be customized to individual risk tolerance and time horizon.

Glide Path and Target-Date Funds

A glide path is a predetermined schedule for gradually reducing equity exposure as retirement approaches and progresses, creating a “bond tent” that provides maximum protection during the highest-risk years.

The rising equity glide path strategy:

- Maximum bond allocation (50-60%) at retirement date

- Gradually increase stock allocation over the first 10-15 years of retirement

- Settle into long-term allocation (typically 60-70% stocks) after sequence risk window

Why this counterintuitive approach works:

- Provides maximum downside protection when the portfolio is largest and most vulnerable

- Reduces equity exposure during the critical first decade when sequence risk is highest

- Increases growth potential after the danger zone passes

- Allows portfolio to benefit from long-term equity returns over a 20-30 year retirement

Target-date funds automate this process, though most use a traditional declining equity glide path (higher stocks early, lower later), which may not optimally address sequence risk.

Research by Wade Pfau and Michael Kitces found that a rising equity glide path improved retirement success rates by 5-10 percentage points compared to static or declining allocations in historical simulations.

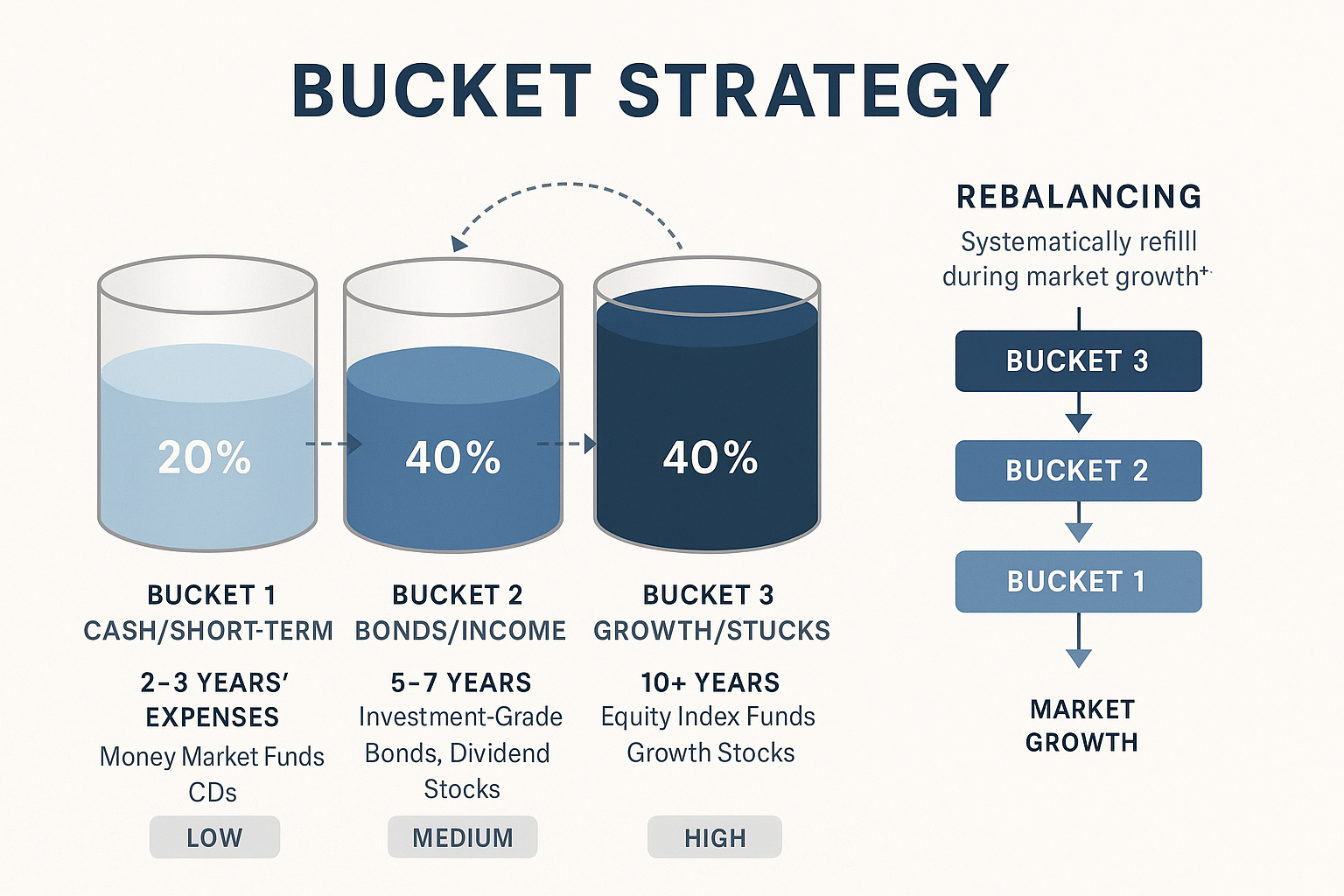

Bucket Strategy

The bucket strategy segments retirement assets into multiple time-based buckets, each with distinct purposes and risk profiles, creating a systematic approach to managing both sequence risk and psychological comfort.

Three-bucket framework:

Bucket 1: Immediate Needs (Cash/Short-term)

- Purpose: Fund 1-3 years of living expenses

- Assets: Money market funds, high-yield savings, short-term CDs

- Risk level: Minimal

- Refill trigger: When depleted to 1 year of expenses

Bucket 2: Medium-term (Income/Bonds)

- Purpose: Fund years 4-10 of expenses

- Assets: Investment-grade bonds, dividend stocks, dividend ETFs

- Risk level: Low to moderate

- Refill trigger: Annually or when Bucket 1 is refilled

Bucket 3: Long-term (Growth/Stocks)

- Purpose: Growth for years 10+ and legacy

- Assets: Stock index funds, growth stocks, REITs

- Risk level: High

- Refill trigger: Never directly withdrawn from; refills Bucket 2 during positive years

How the bucket strategy reduces sequence risk:

- Eliminates forced selling during downturns: Cash bucket provides 2-3 years of cushion, allowing you to avoid selling stocks during bear markets

- Creates psychological comfort: Knowing near-term needs are secure reduces panic during volatility

- Enables opportunistic rebalancing: Refill buckets from winners, naturally implementing “sell high, buy low.”

- Provides a clear decision framework: Removes emotion from withdrawal decisions

When to refill buckets:

- During bull markets: Sell appreciated stocks from Bucket 3, refill Bucket 2, then refill Bucket 1 from Bucket 2

- During bear markets: Draw from Buckets 1 and 2 only; leave Bucket 3 untouched to recover

- Annual review: Rebalance if any bucket drifts more than 10% from target allocation

The bucket strategy essentially creates a dynamic withdrawal system that automatically adjusts to market conditions, providing natural sequence risk protection.

Annuities and Guarantees

Annuities transfer sequence risk from the retiree to an insurance company by providing guaranteed income regardless of market performance, creating a “pension-like” foundation for retirement income.

Types of annuities for sequence risk protection:

Single Premium Immediate Annuity (SPIA):

- Convert a lump sum into a guaranteed lifetime income

- Payments begin immediately

- Eliminates sequence risk for covered expenses

- Irreversible decision (typically no liquidity)

Deferred Income Annuity (DIA):

- Purchase today, income begins at a future date (e.g., age 75)

- Protects against longevity risk and late-life sequence risk

- Lower cost than immediate annuities

- Creates an income “floor” for later retirement years

Fixed Index Annuity (FIA):

- Provides downside protection with limited upside potential

- Returns linked to the market index but with a guaranteed minimum

- More complex with various caps, spreads, and participation rates

- Higher fees than simple annuities

When annuities help with sequence risk:

Good fit when:

- You need a guaranteed income to cover essential expenses

- You have insufficient pension or Social Security income

- You’re anxious about market volatility affecting retirement security

- You want to eliminate sequence risk for a portion of your portfolio

- You’re in good health with longevity in your family

Poor fit when:

- You need liquidity and flexibility

- You have a substantial guaranteed income already (pension, Social Security)

- Fees exceed the value of risk transfer

- You have significant legacy goals for heirs

Optimal annuitization strategy:

Rather than annuitizing the entire portfolio, consider a “flooring” approach:

- Calculate essential expenses not covered by Social Security/pensions

- Annuitize only enough to cover that gap (typically 25-40% of portfolio)

- Invest the remainder in a diversified portfolio for growth and flexibility

- Eliminate sequence risk for basic needs while maintaining upside potential

Research published in the Journal of Financial Planning found that partial annuitization (20-40% of portfolio) combined with a diversified investment portfolio produced higher success rates and greater legacy values than either strategy alone [6].

Dynamic Withdrawal Rules

Dynamic withdrawal strategies adjust spending based on portfolio performance and market conditions, providing flexibility that static withdrawal rates cannot offer.

The Guyton-Klinger Guardrails Method:

This evidence-based approach establishes upper and lower withdrawal “guardrails” that trigger spending adjustments:

Rules:

- Withdrawal rule: Start at a 5-6% initial withdrawal rate (higher than the traditional 4% rule)

- Portfolio management rule: Maintain 60-75% equity allocation

- Capital preservation rule: If withdrawal rate exceeds 20% above initial rate, cut spending by 10%

- Prosperity rule: If withdrawal rate falls 20% below initial rate, increase spending by 10%

Example:

- Start with $1,000,000, withdraw $50,000 (5%)

- After market gains, the portfolio grows to $1,400,000

- Withdrawal rate now 3.57% (29% below initial 5%)

- Prosperity rule triggers: increase withdrawal to $55,000

- After the market decline, the portfolio falls to $900,000

- Withdrawal rate now 6.1% (22% above initial 5%)

- Capital preservation rule triggers: reduce withdrawal to $49,500

Why dynamic rules reduce sequence risk:

- Automatically reduce spending during poor market performance

- Prevent excessive withdrawals that accelerate portfolio depletion

- Allow increased spending during good markets

- Create sustainable withdrawal rates that adapt to actual returns

Other dynamic strategies:

Variable Percentage Withdrawal (VPW):

- Withdraw a fixed percentage of the current portfolio value each year

- Automatically adjusts to market performance

- Eliminates sequence risk but creates income volatility

- Best for retirees with flexible expenses

Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) Method:

- Use IRS RMD tables to calculate withdrawals at any age

- Naturally creates dynamic withdrawals tied to portfolio value

- Conservative approach with very high success rates

- May produce a lower income early in retirement

Ratcheting Rule:

- Never reduce spending below the previous year’s level

- Only increase spending when the portfolio grows significantly

- Provides downside protection with upside flexibility

- Balances sequence risk protection with lifestyle stability

The key insight: flexibility in spending provides powerful sequence risk protection. Retirees willing to reduce spending by 10-20% during severe bear markets can dramatically improve portfolio longevity.

Real Retirement Case Study: The 2008 vs 2012 Retiree

Let’s examine a detailed case study comparing two couples who retired just four years apart, experiencing dramatically different outcomes due to Sequence of Returns Risk.

The Setup: Two Identical Couples

The Johnsons (retired January 2008):

- Ages: Both 65

- Portfolio: $1,000,000 (60% stocks, 40% bonds)

- Withdrawal: $45,000 annually (4.5% initial rate)

- Strategy: Annual inflation adjustments, rebalancing

The Smiths (retired January 2012):

- Ages: Both 65

- Portfolio: $1,000,000 (60% stocks, 40% bonds)

- Withdrawal: $45,000 annually (4.5% initial rate)

- Strategy: Annual inflation adjustments, rebalancing

What Happened: The Sequence Difference

The Johnsons (2008 retiree) experienced:

Year 1 (2008): -37% stock return, -5% bond return

- Portfolio drops to approximately $760,000 after market losses

- Withdraw $45,000 for living expenses

- End year 1 with ~$715,000

Years 2-5 (2009-2012): Recovery period with strong gains

- Markets recover, but from a significantly reduced base

- Continuing withdrawals limit recovery potential

- By the end of 2012: Portfolio approximately $890,000

The Smiths (2012 retiree) experienced:

Year 1 (2012): +16% stock return, +4% bond return

- Portfolio grows to approximately $1,110,000 after market gains

- Withdraw $45,000 for living expenses

- End year 1 with ~$1,065,000

Years 2-5 (2013-2016): Continued bull market

- Strong market performance builds on a larger base

- Withdrawals are a smaller percentage of a growing portfolio

- By the end of 2016: Portfolio approximately $1,340,000

The 15-Year Outcome

After 15 years (through 2023):

The Johnsons (2008 retiree):

- Portfolio value: ~$1,120,000

- Total withdrawn: ~$810,000 (including inflation adjustments)

- Portfolio growth: +12% over 15 years

- Stress level: High during 2008-2009 and 2020 downturns

- Risk of depletion: Moderate if another 2008-level event occurs

The Smiths (2012 retiree):

- Portfolio value: ~$1,680,000

- Total withdrawn: ~$810,000 (including inflation adjustments)

- Portfolio growth: +68% over 15 years

- Stress level: Minimal, portfolio consistently growing

- Risk of depletion: Very low, substantial safety margin

The $560,000 Sequence Gap

Despite identical starting portfolios, withdrawal rates, and strategies, the Smiths have $560,000 more wealth (50% larger portfolio) than the Johnsons after 15 years.

This difference exists purely because of the four-year timing difference; the Johnsons experienced severe negative returns during their critical first years of retirement, while the Smiths enjoyed strong positive returns during their vulnerability window.

Projected 30-year outcomes:

- The Johnsons: Portfolio likely depleted by age 88-92

- The Smiths: Portfolio likely exceeds $2,000,000 by age 95, with substantial legacy

Key Lessons from This Case Study

- Timing matters enormously: Four years made a multi-hundred-thousand-dollar difference

- Early years are critical: The first 5 years of retirement largely determine 30-year outcomes

- Recovery isn’t enough: Markets recovered from 2008, but the Johnsons’ portfolio never fully caught up

- Sequence risk is real: This isn’t a theoretical concern—it’s a documented reality affecting millions of retirees

What the Johnsons could have done differently:

- Implemented a bucket strategy with 3 years of cash before retiring

- Delayed retirement 1-2 years after the 2008 crash

- Reduced equity exposure to 40-50% for the first 5 years

- Used dynamic withdrawal rules to reduce spending 10% in 2008-2009

- Purchased a small SPIA to cover essential expenses

Any of these strategies would have significantly improved their outcome, demonstrating that Sequence of Returns Risk is manageable with proper planning.

Pros and Cons of Sequence Risk Mitigation Strategies

| Strategy | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diversification | • Reduces volatility • Maintains growth potential • Relatively simple • Low cost | • Doesn’t eliminate risk • May reduce returns • Requires rebalancing discipline | Retirees needing a guaranteed income floor with longevity concerns |

| Bucket Strategy | • Psychological comfort • Avoids forced selling • Clear decision framework • Flexible implementation | • Requires active management • May hold excess cash • Can be complex to maintain • Behavioral discipline needed | Retirees who want control and are comfortable with active management |

| Bond Tent/Glide Path | Retirees with a 10+ year planning horizon before retirement | • Counterintuitive (increases stocks in retirement) • May miss early bull markets • Requires discipline to increase risk later | Retirees needing a guaranteed income floor with longevity concerns |

| Annuities | • Eliminates sequence risk for covered income • Guaranteed lifetime income • Simplifies planning | • Irreversible decision • High fees • Reduces flexibility • No legacy for heirs • Inflation risk | Retirees needing guaranteed income floor with longevity concerns |

| Dynamic Withdrawals | • Highly effective risk reduction • Maintains flexibility • Improves success rates • No additional costs | • Income variability • Requires spending discipline • May need to cut expenses • Psychologically challenging | Retirees with flexible expenses and spending discipline |

| Delayed Retirement | • Allows recovery from downturns • Shortens retirement duration • Increases Social Security • Reduces withdrawal rate | • Not always possible • Health may not permit • Sacrifices retirement years • May not be desirable | Those with flexibility in retirement timing and good health |

| Part-time Work | • Reduces portfolio withdrawals • Provides purpose • Maintains flexibility • Can be enjoyable | • Not always available • Health limitations • May defeat retirement purpose | Retirees open to continued work and with marketable skills |

Combined Strategy Approach

The most effective sequence risk protection comes from combining multiple strategies:

Conservative approach (maximum protection):

- 30% bonds/40% stocks/20% annuity/10% cash bucket

- Dynamic withdrawal rules with 10% spending flexibility

- 2-year cash reserve

- Part-time work option for the first 5 years

Moderate approach (balanced protection):

- Bucket strategy (2 years cash, 5 years bonds, remainder stocks)

- Rising equity glide path

- Willingness to reduce spending by 10% if needed

- Diversified across asset classes

Aggressive approach (minimal protection, maximum growth):

- 70% stocks/30% bonds with annual rebalancing

- 3% withdrawal rate (very conservative)

- Large portfolio relative to spending needs

- Flexible spending with significant discretionary expenses

The right combination depends on individual circumstances, risk tolerance, and flexibility in retirement spending.

Pre-Retirement Checklist: Assessing Your Sequence Risk Exposure

Use this comprehensive checklist to evaluate your vulnerability to Sequence of Returns Risk and implement protective measures before retiring.

5-10 Years Before Retirement

Portfolio Assessment:

- [ ] Calculate your planned withdrawal rate (annual expenses ÷ portfolio value)

- [ ] Verify withdrawal rate is 4% or lower (3.5% is safer)

- [ ] Review current asset allocation (% stocks vs. bonds vs. cash)

- [ ] Assess portfolio diversification across asset classes and sectors

- [ ] Calculate how long your portfolio would last in a 2008-style scenario

- [ ] Consider working with a fee-only financial planner for analysis

Income Planning:

- [ ] Estimate Social Security benefits at various claiming ages

- [ ] Calculate pension income (if applicable)

- [ ] Identify guaranteed income sources (annuities, rental income, part-time work)

- [ ] Determine the gap between guaranteed income and essential expenses

- [ ] Consider delaying Social Security to age 70 for maximum benefit

- [ ] Evaluate whether essential expenses are covered by guaranteed sources

Risk Mitigation Implementation:

- [ ] Begin building a 2-3 year cash reserve for retirement start

- [ ] Implement bucket strategy framework

- [ ] Consider bond tent strategy (increase bonds, then decrease over time)

- [ ] Research appropriate annuity products for income floor (if needed)

- [ ] Establish a dynamic withdrawal rule framework

- [ ] Review and improve diversification

1-2 Years Before Retirement

Market Timing Considerations:

- [ ] Assess current market valuations (P/E ratios, CAPE ratios)

- [ ] Evaluate recent market performance (are we near all-time highs?)

- [ ] Consider delaying retirement 6-12 months if the market is severely overvalued

- [ ] Build flexibility into retirement date (avoid rigid timing)

- [ ] Have a plan for what you’d do if the market crashes right before your retirement date

Final Portfolio Adjustments:

- [ ] Complete transition to retirement asset allocation

- [ ] Ensure cash bucket is fully funded (2-3 years of expenses)

- [ ] Verify bond allocation provides adequate protection

- [ ] Confirm diversification across multiple asset classes

- [ ] Set up an automatic rebalancing system

- [ ] Document withdrawal strategy and rules

Expense Planning

- [ ] Create detailed retirement budget (essential vs. discretionary expenses)

- [ ] Identify expenses you could reduce by 10-20% if needed

- [ ] Plan for healthcare costs and insurance

- [ ] Consider downsizing or relocating to reduce fixed expenses

- [ ] Build in flexibility for dynamic withdrawal adjustments

At Retirement

Implementation:

- [ ] Execute bucket strategy setup

- [ ] Establish withdrawal schedule and amount

- [ ] Set calendar reminders for annual portfolio review

- [ ] Document decision rules for spending adjustments

- [ ] Create a plan for rebalancing during market extremes

- [ ] Consider part-time work for the first 2-3 years as a buffer

Ongoing Monitoring:

- [ ] Review portfolio quarterly for major deviations

- [ ] Rebalance annually or when allocations drift >10%

- [ ] Assess withdrawal rate annually (should stay under 5-6%)

- [ ] Adjust spending if portfolio declines >20% from peak

- [ ] Refill cash bucket from bonds/stocks during positive years

- [ ] Revisit strategy every 3-5 years or after major market events

Emergency Protocols:

- [ ] Define what constitutes a “sequence risk event” (e.g., portfolio down >25%)

- [ ] Pre-commit to spending reduction percentage if triggered

- [ ] Identify discretionary expenses to cut first

- [ ] Consider part-time work or delaying major purchases

- [ ] Avoid panic selling, stick to predetermined rules

- [ ] Consult a financial advisor before making major changes

Risk Tolerance Assessment

Answer these questions honestly:

- Could you reduce spending by 10-15% for 2-3 years if markets crashed early in retirement?

- Yes → Lower sequence risk concern

- No → Need more guaranteed income or larger cash reserves

- How would you feel if your portfolio dropped 30% in your first year of retirement?

- Concerned but confident in my plan → Moderate risk tolerance

- Panicked and likely to make changes → Need more conservative allocation

- What percentage of your expenses are truly essential (housing, food, healthcare)?

- <60% → Good flexibility for dynamic withdrawals

- >80% → Consider annuity for income floor

- Do you have income sources beyond your portfolio (Social Security, pension, rental income)?

- Yes, covering >50% of expenses → Lower sequence risk

- No, portfolio funds everything → Higher sequence risk, need more protection

- Could you work part-time for 2-3 years if needed?

- Yes → Excellent sequence risk buffer

- No → Build larger cash reserves and lower withdrawal rate

Your answers should guide which mitigation strategies to prioritize. The more “high risk” answers, the more conservative your approach should be.

Interactive Tool: Sequence of Returns Risk Calculator

📊 Sequence of Returns Risk Calculator

Compare two retirement scenarios with identical average returns but different sequences

Conclusion: Taking Control of Your Retirement Sequence Risk

Sequence of Returns Risk represents one of the most significant yet least understood threats to retirement security. The math behind money reveals an uncomfortable truth: the timing of returns matters just as much as the average return when you’re withdrawing funds to support your lifestyle.

The evidence is clear and data-driven:

- Two retirees with identical portfolios, withdrawal rates, and average returns can experience radically different outcomes based solely on the sequence in which returns occur

- The first 10-15 years of retirement represent the critical “sequence risk zone” when portfolio outcomes are largely determined

- Poor returns early in retirement can permanently damage portfolio longevity, even if markets eventually recover

- Withdrawals during market downturns create dollar-cost averaging, forcing the sale of more shares at depressed prices and reducing future compounding capacity

But understanding the risk is only the first step. The real power comes from implementing evidence-based strategies to protect against it:

Immediate actions you can take:

- Assess your exposure using the pre-retirement checklist, calculate your withdrawal rate, evaluate your asset allocation, and determine your flexibility in spending

- Build a cash buffer of 2-3 years of expenses before retiring to avoid forced selling during downturns

- Implement a bucket strategy to segment your portfolio by time horizon and risk level

- Establish dynamic withdrawal rules that allow spending flexibility based on market performance

- Diversify strategically across asset classes to smooth returns and reduce volatility

- Consider partial annuitization for essential expenses to create a guaranteed income floor

The sequence risk mindset shift:

Moving from accumulation to decumulation requires fundamentally rethinking your relationship with market volatility. What helped you build wealth, staying fully invested through downturns, maintaining high equity allocations, and ignoring short-term fluctuations, may not serve you well in retirement.

Successful retirement requires:

- Flexibility in spending to adjust to market realities

- Protection through appropriate asset allocation and cash reserves

- Discipline to follow predetermined rules rather than emotional reactions

- Planning that accounts for worst-case scenarios, not just average outcomes

Your next steps:

If you’re 10+ years from retirement: Focus on maximizing accumulation while beginning to understand sequence risk. Build wealth through compound growth and evidence-based investing, but start planning your transition strategy.

If you’re 5-10 years from retirement: Actively implement sequence risk mitigation. Build your cash bucket, establish your withdrawal strategy, consider a bond ladder approach, and create flexibility in your retirement timing.

If you’re 1-2 years from retirement: Fine-tune your protection strategies. Ensure cash reserves are fully funded, document your withdrawal rules, assess current market valuations, and build flexibility into your retirement date.

If you’re already retired: Review your current strategy against sequence risk principles. If you’ve experienced strong early returns, consider building larger cash reserves and potentially reducing equity exposure. If you’ve experienced poor early returns, implement spending flexibility and avoid panic selling.

The mathematical reality of retirement:

Sequence of Returns Risk isn’t a theoretical concern—it’s a documented phenomenon that has devastated unprepared retirees throughout history. The 2000-2002 tech crash, the 2008-2009 financial crisis, and the 2020 pandemic crash all created sequence risk events that permanently altered retirement outcomes for millions.

But it’s also a manageable risk. With proper planning, evidence-based strategies, and disciplined implementation, you can protect your retirement security while maintaining growth potential and lifestyle flexibility.

The math behind money doesn’t lie: sequence matters. But armed with data-driven insights and proven strategies, you can turn this knowledge into action and build a retirement that weathers any sequence of returns the market delivers.

Your financial future depends not just on how much you save or what returns you earn, but on how well you manage the sequence in which those returns occur. Start planning today—your future self will thank you.

References

[1] Bengen, William P. “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data.” Journal of Financial Planning, October 1994.

[2] Kitces, Michael. “Understanding Sequence of Return Risk – Safe Withdrawal Rates, Bear Market Crashes, and Bad Decades.” Nerd’s Eye View, Kitces.com, 2015.

[3] Pfau, Wade D. “The Importance of Sequence of Returns in Retirement.” Retirement Researcher, 2014.

[4] Vanguard Research. “Vanguard’s Principles for Investing Success.” Vanguard Group, 2023. https://investor.vanguard.com

[5] Kitces, Michael E., and Pfau, Wade D. “Reducing Retirement Risk with a Rising Equity Glide Path.” Journal of Financial Planning, January 2015.

[6] Milevsky, Moshe A., and Young, Virginia R. “Annuitization and Asset Allocation.” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 31, 2007.

[7] Guyton, Jonathan T., and Klinger, William J. “Decision Rules and Maximum Initial Withdrawal Rates.” Journal of Financial Planning, March 2006.

[8] Morningstar Research. “The State of Retirement Income: Safe Withdrawal Rates.” Morningstar Investment Management, 2023. https://www.morningstar.com

Legal Disclaimer

Educational Purpose Only: This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. The content represents general information about the sequence of returns, risk, and retirement planning concepts.

Not Personalized Advice: The strategies, examples, and recommendations discussed are not tailored to any individual’s specific financial situation, goals, risk tolerance, or circumstances. What works for one person may not be appropriate for another.

No Guarantees: Past performance does not guarantee future results. All investments carry risk, including the potential loss of principal. Market conditions, economic factors, and personal circumstances can significantly impact retirement outcomes.

Consult Professionals: Before making any financial decisions, retirement planning choices, or investment changes, consult with qualified professionals, including:

- Certified Financial Planner (CFP®)

- Registered Investment Advisor (RIA)

- Tax professional (CPA or EA)

- Estate planning attorney (if applicable)

Hypothetical Examples: All case studies, scenarios, and examples in this article are hypothetical illustrations designed to demonstrate concepts. They do not represent actual client experiences or guaranteed outcomes.

No Client Relationship: Reading this article does not create a client-advisor relationship. The Rich Guy Math and Max Fonji do not provide personalized financial advice through published content.

Third-Party Links: Links to external websites are provided for convenience and informational purposes only. The Rich Guy Math does not endorse, control, or assume responsibility for the content, accuracy, or practices of third-party sites.

Current as of 2025: Financial regulations, tax laws, and market conditions change frequently. Information in this article is current as of 2025, but it may become outdated. Verify current rules and conditions before making decisions.

Your Responsibility: You are solely responsible for evaluating the accuracy, completeness, and usefulness of any information or content in this article and for any decisions you make based on it.

By using this information, you acknowledge that you understand and accept these limitations and disclaimers.

About the Author

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform dedicated to explaining the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and risk management.

With a background in financial analysis and a passion for evidence-based investing, Max translates complex financial concepts into clear, actionable insights for beginner to intermediate investors. His approach combines rigorous data analysis with practical application, helping readers understand not just what to do with their money, but why it works.

Max’s work focuses on demystifying the math behind money, from compound interest and valuation principles to retirement planning and sequence risk management. His writing has helped thousands of readers make more informed financial decisions based on evidence rather than emotion.

The Rich Guy Math philosophy: Every financial decision has underlying mathematics. Understanding those numbers gives you power over your financial future.

Connect with Max and explore more evidence-based financial education at The Rich Guy Math.

Frequently Asked Questions About Sequence of Returns Risk

What is the sequence of returns risk in simple terms?

Sequence of returns risk is the danger that experiencing poor investment returns early in retirement—when you’re withdrawing money—can permanently damage your portfolio’s ability to last throughout retirement, even if markets eventually recover. The order in which you experience returns matters as much as the average return when you’re taking withdrawals.

When does the sequence of returns risk matter most?

Sequence risk matters most during the first 10-15 years of retirement and the 5 years before retirement. These periods represent the “sequence risk zone” when your portfolio is largest and most vulnerable to market downturns combined with withdrawals. During the accumulation phase, sequence risk is negligible or even beneficial.

How is sequence of returns risk different from market risk?

Market risk is the general possibility that investments will decline in value. Sequence of returns risk is specifically about the timing of those declines relative to when you’re making withdrawals. Two investors can experience identical market risk but completely different outcomes based on when the bad years occur in their retirement timeline.

What withdrawal rate is safe given sequence of returns risk?

Research suggests a 4% initial withdrawal rate (adjusted annually for inflation) provides roughly 90–95% probability of lasting 30 years, even accounting for sequence risk. More conservative retirees may prefer 3–3.5% for greater security, while those with flexible spending or other income sources might sustain 5–6% using dynamic withdrawal rules. The 4% rule was originally designed around historical worst-case sequence risk periods.

Can you eliminate sequence of returns risk completely?

No single strategy eliminates sequence risk entirely, but it can be reduced significantly by combining approaches:

- Maintaining 2–3 years of expenses in cash

- Using a bucket strategy

- Implementing dynamic withdrawal rules

- Purchasing annuities for essential expenses

- Maintaining flexibility in retirement spending

The closest to “eliminating” sequence risk is annuitizing the entire portfolio, but this sacrifices flexibility and legacy goals.

Should I delay retirement if the market just crashed?

If possible, delaying retirement by 1–2 years after a major crash can meaningfully improve outcomes by allowing the portfolio to recover before withdrawals begin. If delaying is not an option, alternatives include reducing initial withdrawals, taking part-time work, using a larger cash buffer, or temporarily cutting discretionary spending.

How do bonds help with sequence of returns risk?

Bonds help reduce sequence risk by providing stability and often rising when stocks fall. High-quality bonds can be used for withdrawals during market downturns, reducing the need to sell stocks at depressed prices. This preserves stock holdings so they can participate in the recovery. A 40–60% bond allocation early in retirement significantly reduces sequence risk.

What’s the difference between sequence risk and longevity risk?

Sequence risk is the danger of poor returns early in retirement depleting the portfolio prematurely. Longevity risk is the danger of outliving your money due to living longer than expected. They are related but separate: sequence risk can damage a portfolio quickly, while longevity risk results from extended time horizons.

Is a 60/40 portfolio still good for managing sequence risk in 2025?

The traditional 60% stock / 40% bond portfolio remains a reasonable starting point. With higher bond yields in 2025, the 60/40 model has regained some resilience. Many advisors now recommend dynamic approaches such as a rising equity glide path (starting at 40/60 and increasing to 70/30) or a bucket strategy for enhanced sequence risk protection.

How did retirees in 2008 handle sequence of returns risk?

Retirees who stayed invested, reduced spending temporarily, drew from cash buffers, or took part-time work generally recovered with the subsequent market rebound. Those who panicked, sold out of equities, or moved fully into cash locked in losses and often experienced permanent portfolio damage.

Can dollar-cost averaging help with sequence risk in retirement?

No. Dollar-cost averaging helps during accumulation but not during withdrawals. In retirement, you face “reverse dollar-cost averaging,” where selling shares during downturns accelerates depletion. The solution is maintaining cash reserves to avoid selling stocks when prices are low.

Should I use a robo-advisor to manage sequence risk?

Robo-advisors can assist through rebalancing, tax-loss harvesting, and glide path management, but most use static withdrawal rules, limiting protection. They are most effective when paired with human oversight or a bucket strategy. Combining a robo-advisor with dynamic withdrawal rules provides stronger sequence risk protection.