Most people avoid finance because the language sounds foreign. Terms like “liquidity,” “equity,” and “EBITDA” create an invisible wall between beginners and wealth-building knowledge.

But here’s the truth: finance isn’t complicated once someone explains the math behind money in plain English. Every financial concept follows logical cause and effect. Every ratio tells a story. Every statement reveals patterns that determine success or failure.

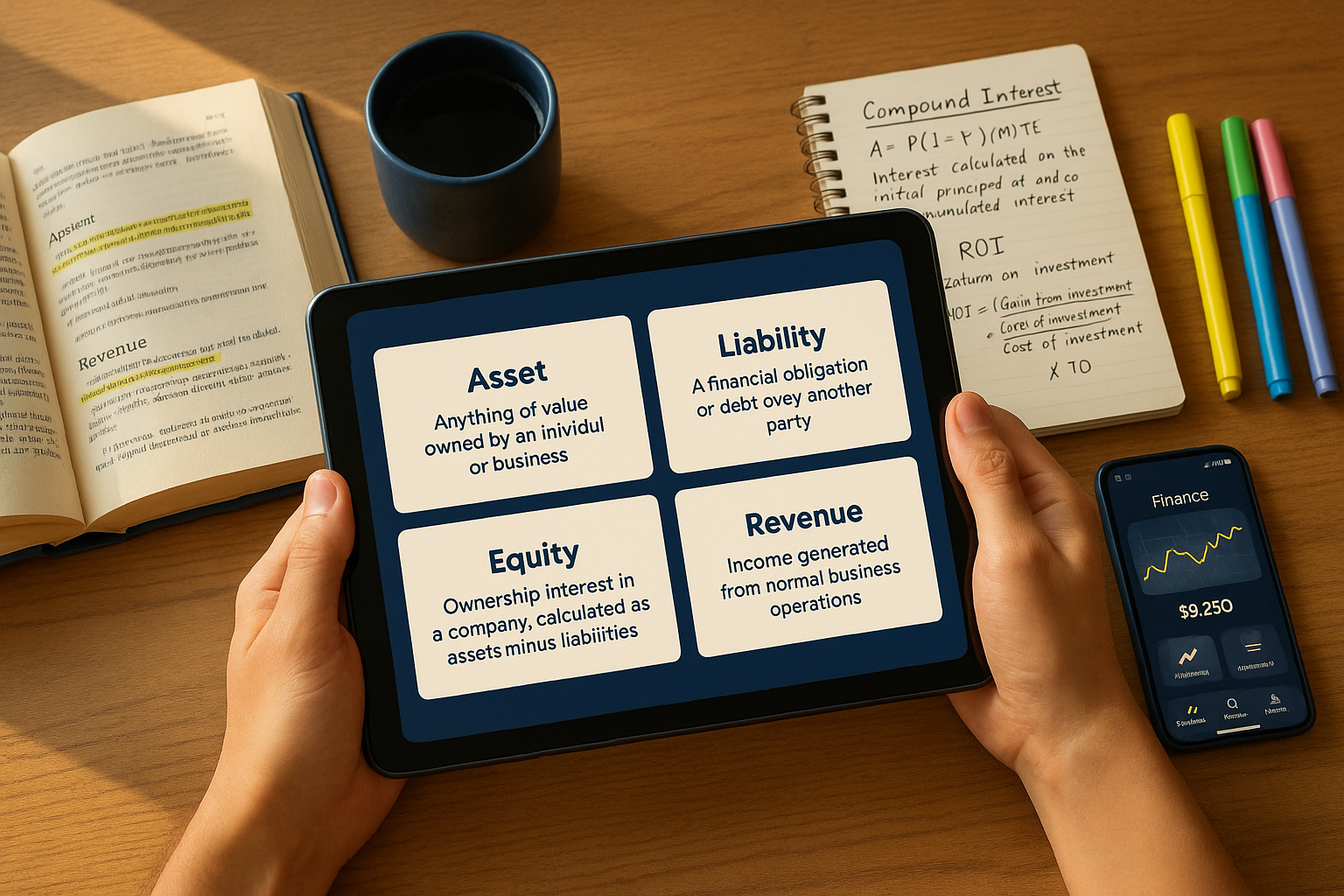

This Finance Cheat Sheet breaks down the essential definitions every beginner needs to understand how money actually works. No jargon without explanation. No concepts without context. Just clear, data-driven insights that build financial literacy from the ground up.

The definitions below form the foundation of investing fundamentals, business analysis, and personal wealth building. Master these terms, and financial statements transform from confusing documents into readable roadmaps.

Key Takeaways

- The accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) forms the backbone of all financial analysis, and understanding this relationship unlocks balance sheet comprehension

- Five core ratio categories (profitability, liquidity, efficiency, solvency, valuation) each serve specific analytical purposes that reveal different aspects of financial health

- Three financial statements (Balance Sheet, Income Statement, Cash Flow Statement) work together to provide a complete picture of business performance and position

- Liquidity ratios measure short-term financial health, with increasing levels of conservatism from the Current Ratio to the Quick Ratio to the Cash Ratio

- Financial literacy starts with simple definitions that connect mathematical relationships to real-world money decisions and wealth-building strategies

Understanding the Foundation: Core Accounting Concepts

The Fundamental Accounting Equation

The entire structure of financial analysis rests on one simple formula:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

This equation must always balance. Assets represent everything a business owns. Liabilities represent everything a business owes. Equity represents the ownership stake remaining after subtracting liabilities from assets.

Think of it this way: if a company owns $100,000 in assets and owes $60,000 in liabilities, the equity equals $40,000. That’s the true value belonging to owners.

This relationship drives every transaction. When a business takes a loan, both assets (cash) and liabilities (debt) increase by the same amount. The equation stays balanced. When a company earns profit, assets increase while equity increases through retained earnings.

Takeaway: The accounting equation isn’t just theory. It’s the mathematical proof that every financial transaction has two sides, and understanding this dual nature prevents confusion when analyzing balance sheet basics.

Assets: What You Own

Assets fall into two main categories: current and non-current.

Current assets convert to cash within one year. This includes:

- Cash and cash equivalents

- Accounts receivable (money customers owe)

- Inventory

- Marketable securities

Non-current assets provide value over multiple years:

- Property, plant, and equipment

- Intangible assets (patents, trademarks)

- Long-term investments

- Goodwill

The distinction matters because liquidity, the ability to quickly access cash, determines financial flexibility. A company with $1 million in real estate but only $5,000 in cash faces different challenges than one with $500,000 in liquid assets.

Liabilities: What You Owe

Liabilities represent obligations that require future payment.

Current liabilities come due within one year:

- Accounts payable (money owed to suppliers)

- Short-term debt

- Accrued expenses

- Deferred revenue

Non-current liabilities extend beyond one year:

- Long-term debt

- Pension obligations

- Deferred tax liabilities

The timing of liabilities matters enormously. A business with $100,000 in debt due next month faces immediate pressure. The same debt spread over 10 years creates manageable payments.

Understanding the difference between assets vs liabilities forms the first step toward financial literacy. Assets build wealth. Liabilities consume it. The goal: acquire assets that appreciate while minimizing liabilities that drain resources.

Equity: The Ownership Stake

Equity represents the residual claim on assets after paying all liabilities.

For businesses, equity includes:

- Common stock (initial investment)

- Retained earnings (accumulated profits)

- Additional paid-in capital

- Treasury stock (repurchased shares)

For individuals, equity appears in home ownership. A house worth $400,000 with a $250,000 mortgage carries $150,000 in equity. As the mortgage decreases and the property value increases, equity grows.

The relationship between debt and equity determines financial leverage. Companies with high debt relative to equity carry more risk but potentially higher returns. Those with low debt maintain stability but may sacrifice growth opportunities.

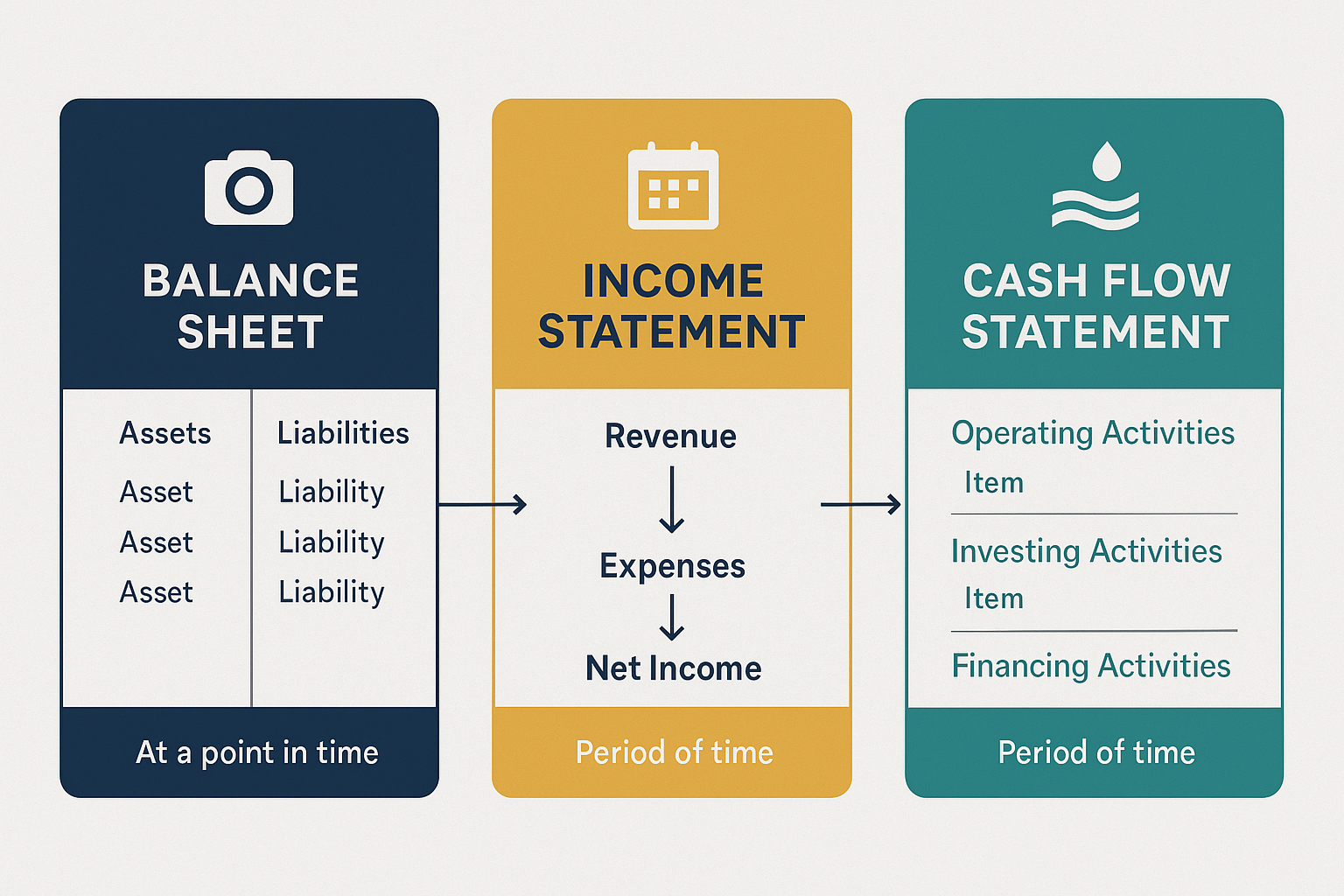

The Three Essential Financial Statements

Balance Sheet: The Financial Snapshot

A balance sheet captures financial position at a specific moment in time, like a photograph of wealth.

The structure follows the accounting equation:

Assets (left side) = Liabilities + Equity (right side)

Reading a balance sheet reveals:

- Liquidity: Can the business pay immediate bills?

- Solvency: Can the business survive long-term?

- Capital structure: How much debt funds operations?

Example balance sheet (simplified):

| Assets | Amount | Liabilities & Equity | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | $50,000 | Accounts Payable | $30,000 |

| Accounts Receivable | $75,000 | Short-term Debt | $20,000 |

| Inventory | $100,000 | Long-term Debt | $80,000 |

| Equipment | $155,000 | Total Liabilities | $130,000 |

| Equity | $250,000 | ||

| Total Assets | $380,000 | Total Liab. + Equity | $380,000 |

The balance sheet answers the question: “What does this entity own, owe, and truly control?”

For deeper analysis, see our complete guide on balance sheet basics.

Income Statement: The Profitability Report

The income statement measures performance over a period, like a movie showing financial activity.

The basic structure:

Revenue – Expenses = Net Income

Key components include:

- Revenue: Total sales or income

- Cost of Goods Sold (COGS): Direct costs of production

- Gross Profit: Revenue minus COGS

- Operating Expenses: Salaries, rent, marketing

- Operating Income: Gross profit minus operating expenses

- Net Income: Final profit after all expenses and taxes

Example income statement:

| Item | Amount |

|---|---|

| Revenue | $500,000 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | -$200,000 |

| Gross Profit | $300,000 |

| Operating Expenses | -$150,000 |

| Operating Income | $150,000 |

| Interest & Taxes | -$50,000 |

| Net Income | $100,000 |

The income statement reveals profitability trends. Growing revenue with shrinking expenses signals efficiency. Declining margins indicate pricing pressure or cost inflation.

Cash Flow Statement: The Liquidity Tracker

The cash flow statement tracks actual cash movement through three categories:

1. Operating Activities

Cash from core business operations:

- Collections from customers

- Payments to suppliers

- Salary payments

- Tax payments

2. Investing Activities

Cash used for growth:

- Equipment purchases

- Asset sales

- Investment acquisitions

3. Financing Activities

Cash from funding sources:

- Debt issuance or repayment

- Stock sales or buybacks

- Dividend payments

The critical insight: profit doesn’t equal cash. A company can show net income while running out of cash if customers pay slowly or inventory piles up.

Takeaway: All three statements work together. The balance sheet shows the position. The income statement shows profitability. The cash flow statement shows liquidity. Analyzing one without the others creates an incomplete understanding.

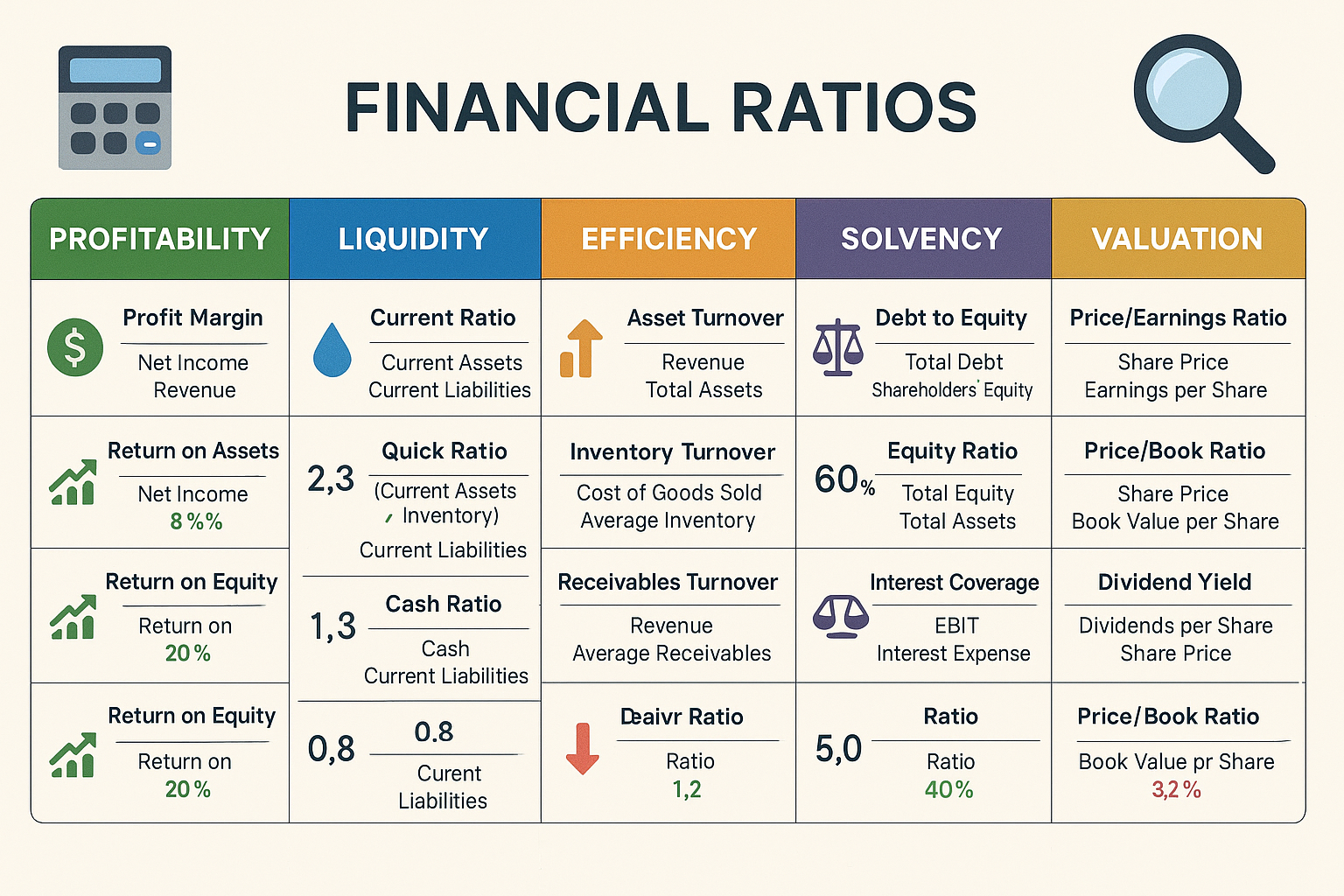

Financial Ratios: The Numbers That Matter

Financial ratios convert raw data into meaningful comparisons. They answer specific questions about business health and performance.

Liquidity Ratios: Can You Pay Your Bills?

Current Ratio = Current Assets ÷ Current Liabilities

Liquidity Ratios measure the ability to cover short-term obligations with short-term assets.

A current ratio of 2.0 means $2 in current assets for every $1 in current liabilities. Generally, ratios above 1.5 indicate healthy liquidity, though optimal levels vary by industry.

Retailers often operate with lower ratios (1.0-1.5) because inventory turns quickly. Manufacturing companies need higher ratios (2.0+) due to longer production cycles.

For detailed analysis, see our guide on the current ratio.

Quick Ratio = (Current Assets – Inventory) ÷ Current Liabilities

The quick ratio provides a more conservative measure by removing inventory, the least liquid current asset.

Why exclude inventory? Because converting inventory to cash takes time. During financial stress, inventory may sell at steep discounts or not at all.

A quick ratio above 1.0 suggests a company can meet immediate obligations without selling inventory. Ratios below 0.5 signal potential liquidity problems.

See our full guide about current ratio vs quick ratio differences.

Cash Ratio = (Cash + Cash Equivalents) ÷ Current Liabilities

The most conservative liquidity measure shows only immediately available cash.

A cash ratio of 0.5 means $0.50 in cash for every $1 in current liabilities. While lower than other ratios, this metric reveals true emergency capacity.

Companies with strong cash ratios survive unexpected shocks, economic downturns, supply disruptions, or customer payment delays.

Profitability Ratios: Are You Making Money?

Gross Profit Margin = (Revenue – COGS) ÷ Revenue × 100%

Profitability ratios reveal how much profit remains after direct production costs.

A 40% gross margin means $0.40 profit from each $1 in sales before operating expenses. Higher margins indicate pricing power or efficient production.

Software companies often achieve 70-90% gross margins because digital products cost little to reproduce. Retailers typically see 20-40% margins due to inventory costs.

Net Profit Margin = Net Income ÷ Revenue × 100%

The bottom-line profitability measure shows what percentage of revenue becomes actual profit.

A 10% net margin means $0.10 profit from each $1 in sales after all expenses. This ratio varies dramatically by industry. Grocery stores operate on 1-3% margins while pharmaceutical companies may achieve 20%+ margins.

Return on Equity (ROE) = Net Income ÷ Shareholder Equity × 100%

ROE measures how effectively a company generates profit from shareholder investment.

A return on equity (ROE) of 15% means each $1 of equity generates $0.15 in annual profit. Warren Buffett seeks companies with consistent ROE above 15%, indicating sustainable competitive advantages.

Return on Assets (ROA) = Net Income ÷ Total Assets × 100%

ROA shows how efficiently a company uses all its assets to generate profit.

A 5% return on assets (ROA) means each $1 in assets produces $0.05 in annual profit. Capital-intensive industries (utilities, manufacturing) typically show lower ROA than asset-light businesses (consulting, software).

Efficiency Ratios: How Well Do You Operate?

Inventory Turnover = Cost of Goods Sold ÷ Average Inventory

The Efficiency ratio measures how many times inventory sells and is replaced during a period.

A turnover of 6 means inventory cycles six times annually, roughly every two months. Higher turnover indicates efficient inventory management and strong sales.

Grocery stores achieve turnover rates of 10-15 because perishable goods move quickly. Furniture retailers may see turnover of 3-4 due to slower sales cycles.

Accounts Receivable Turnover = Net Credit Sales ÷ Average Accounts Receivable

This ratio shows how quickly a company collects customer payments.

A turnover of 8 means receivables convert to cash eight times per year, approximately every 45 days. Higher turnover indicates efficient collection processes and creditworthy customers.

Solvency Ratios: Can You Survive Long-Term?

Debt-to-Equity Ratio = Total Liabilities ÷ Shareholder Equity

Solvency Ratios reveal financial leverage and risk exposure.

A ratio of 1.5 means $1.50 in debt for every $1 in equity. Higher ratios indicate greater financial risk but potentially higher returns if operations succeed.

Conservative investors prefer ratios below 1.0. Growth companies often operate with ratios of 2.0+ to fund expansion.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio = Operating Income ÷ Total Debt Service

This ratio measures the ability to cover debt payments from operating income.

A ratio of 2.0 means operating income covers debt payments twice over. Lenders typically require ratios above 1.25 for loan approval.

Valuation Ratios: What’s It Worth?

Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio = Stock Price ÷ Earnings Per Share

The P/E ratios show how much investors pay for each dollar of earnings.

A P/E of 20 means investors pay $20 for $1 in annual earnings. Higher ratios suggest growth expectations or market optimism. Lower ratios may indicate value opportunities or business concerns.

Earnings Per Share (EPS) = Net Income ÷ Outstanding Shares

EPS measures profit allocated to each share of stock.

Growing EPS indicates improving profitability or share buybacks. Declining EPS signals weakening performance or share dilution.

Takeaway: No single ratio tells the complete story. Analyze multiple ratios across categories to understand financial health comprehensively. Compare ratios to industry benchmarks and historical trends for meaningful context.

Essential Finance Terms for Everyday Use

Interest and Compounding

Simple Interest = Principal × Rate × Time

Simple interest calculates returns on the initial principal only.

$10,000 at 5% simple interest for 3 years generates $1,500 in interest ($10,000 × 0.05 × 3).

Compound Interest = Principal × (1 + Rate)^Time – Principal

Compound interest calculates returns on both principal and accumulated interest, the foundation of wealth building.

$10,000 at 5% compound interest for 3 years generates $1,576.25 in interest. The extra $76.25 comes from interest earned.

Over decades, compound growth creates exponential wealth. This mathematical reality drives long-term investing success.

For detailed calculations, see our compound interest calculator guide and learn about compound vs simple interest.

APR vs APY

Annual Percentage Rate (APR) measures the yearly cost of borrowing without compounding.

A credit card with 18% APR charges 18% annually on outstanding balances.

Annual Percentage Yield (APY) measures the yearly return, including compounding effects.

A savings account with 5% APY that compounds monthly delivers slightly more than 5% actual return due to monthly compounding.

Understanding APY vs APR prevents costly mistakes when comparing financial products.

Depreciation and Amortization

Depreciation spreads the cost of tangible assets over their useful life.

A $100,000 machine with a 10-year life depreciates $10,000 annually using straight-line depreciation. This accounting practice matches expenses with revenue-generating periods.

Amortization applies the same concept to intangible assets like patents or goodwill.

The difference between amortization vs depreciation lies in asset type, not calculation method.

EBITDA: Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization

EBITDA measures operating performance before financing and accounting decisions.

EBITDA = Net Income + Interest + Taxes + Depreciation + Amortization

This metric enables comparison between companies with different capital structures and tax situations. A company with high debt shows lower net income due to interest expenses, but EBITDA reveals underlying operational performance.

Critics argue that EBITDA ignores real costs like capital expenditures. Supporters value it for operational comparisons.

The EBITDA margin (EBITDA ÷ Revenue) shows what percentage of sales converts to operating cash flow before non-operating items.

Economic Profit vs Accounting Profit

Accounting profit follows GAAP rules: Revenue minus explicit costs.

A business with $500,000 in revenue and $400,000 in expenses shows $100,000 accounting profit.

Economic profit subtracts opportunity costs, which could have been earned with resources deployed elsewhere.

If that same business required $1,000,000 in capital that could have earned 12% elsewhere ($120,000), the economic profit equals -$20,000. The business generates accounting profit but destroys economic value.

Understanding economic vs accounting profit reveals whether a business truly creates wealth or merely appears profitable.

Revenue Recognition

Deferred Revenue represents payments received before delivering goods or services.

A software company collecting annual subscriptions upfront records deferred revenue as a liability. As service is delivered monthly, revenue is recognized proportionally.

Learn more about deferred revenue explained.

Accrual Accounting records revenue when earned and expenses when incurred, regardless of cash movement.

Cash Accounting records transactions only when cash changes hands.

The difference between cash vs accrual accounting dramatically affects reported profitability and timing.

Budgeting Rules

50/30/20 Rule: Allocate 50% of income to needs, 30% to wants, 20% to savings and debt repayment.

This simple framework creates financial balance without complex tracking.

4% Rule: Withdraw 4% of retirement savings annually for sustainable income.

A $1,000,000 portfolio supports $40,000 in annual withdrawals with a high probability of lasting 30+ years.

3x Rent Rule: Monthly income should be at least three times the monthly rent.

This guideline prevents housing costs from overwhelming budgets.

Takeaway: These practical rules translate financial theory into actionable decisions. They provide starting points for personal financial planning based on proven mathematical relationships.

Building Your Financial Vocabulary: Advanced Terms

Leverage and Capital Structure

Financial Leverage uses debt to amplify potential returns.

A company investing $100,000 of equity plus $400,000 of debt ($500,000 total) in a project that returns 10% earns $50,000. After paying 5% interest on debt ($20,000), the net return equals $30,000 on $100,000 equity, a 30% return.

The same project, funded entirely with equity, delivers only a 10% return. Leverage multiplies gains but also magnifies losses.

Capital Structure describes the mix of debt and equity funding operations.

Optimal capital structure balances the tax benefits of debt against bankruptcy risk. Companies in stable industries (utilities, consumer staples) support higher debt levels than those in volatile sectors (technology, biotechnology).

The degree of Operating Leverage measures how revenue changes affect operating income.

High operating leverage means small revenue increases generate large profit gains, but small decreases cause steep profit declines.

Working Capital Management

Working Capital = Current Assets – Current Liabilities

Positive working capital indicates sufficient short-term assets to cover short-term obligations. Negative working capital suggests potential liquidity problems.

The Cash Conversion Cycle measures how long cash remains tied up in operations:

Cash Conversion Cycle = Days Inventory Outstanding + Days Sales Outstanding – Days Payable Outstanding

Shorter cycles mean faster cash generation. Amazon’s negative cash conversion cycle, collecting customer payments before paying suppliers, funds growth without external financing.

Risk and Return Concepts

Diversification reduces risk by spreading investments across uncorrelated assets.

A portfolio holding 30 stocks from different industries experiences lower volatility than one holding a single stock. Diversification eliminates company-specific risk while maintaining market exposure.

Dollar-Cost Averaging invests fixed amounts at regular intervals regardless of price.

Investing $500 monthly buys more shares when prices fall and fewer when prices rise, reducing the average cost per share over time. This strategy removes emotion from investing and builds positions systematically.

Compare dollar-cost averaging vs lump sum approaches to understand timing strategies.

Use our dollar-cost averaging calculator to model different scenarios.

Income Types

Active Income requires ongoing effort, salaries, wages, and business profits from direct involvement.

Passive Income generates returns without continuous work, rental income, dividends, and royalties.

Understanding active vs passive income shapes wealth-building strategies. Active income funds make initial investments. Passive income creates financial independence.

Earned Income comes from employment or self-employment and faces the highest tax rates.

Investment income often receives preferential tax treatment, making asset accumulation more efficient than income maximization alone.

Putting It All Together: From Definitions to Decisions

Financial literacy isn’t about memorizing definitions. It’s about connecting mathematical relationships to real-world decisions.

Consider a practical example:

Scenario: Evaluating two job offers.

Offer A: $80,000 salary, no benefits, contract position

Offer B: $70,000 salary, full benefits (health insurance worth $8,000, 401(k) match worth $3,500), permanent position

Surface analysis favors Offer A, higher cash compensation.

Deeper analysis considers total compensation:

- Offer A: $80,000 total

- Offer B: $70,000 + $8,000 + $3,500 = $81,500 total

But the complete picture includes risk assessment:

- Offer A carries employment uncertainty

- Offer B provides stability and compound growth through retirement matching

The 401(k) match represents an immediate 100% return on invested funds, unmatched in traditional investing. Over 30 years, the $3,500 annual match has grown at 8% compound to over $400,000.

This example demonstrates how financial definitions connect to life decisions. Understanding compound growth, risk management, and total compensation analysis leads to better choices.

The Data-Driven Approach

Every financial decision should follow a systematic process:

- Define the question: What outcome matters most?

- Gather relevant data: What numbers inform this decision?

- Apply appropriate formulas: Which calculations reveal the truth?

- Compare alternatives: What trade-offs exist?

- Consider time horizons: How do results change over periods?

- Account for risk: What could go wrong?

- Make the decision: Choose based on evidence, not emotion

This framework applies whether evaluating job offers, comparing investment options, or analyzing business opportunities.

Building Financial Confidence

Financial confidence grows through practice, not perfection.

Start with one concept. Master the accounting equation. Understand how assets, liabilities, and equity relate. Then add another layer, learn to read income statements. Build gradually.

Each new definition adds another tool. Each ratio provides another lens. Over time, financial statements transform from intimidating documents into readable stories about business performance and financial health.

The goal isn’t to become an accountant or financial analyst. The goal is to make informed decisions based on evidence rather than guesses.

Conclusion

This Finance Cheat Sheet provides the essential definitions that unlock financial literacy. From the fundamental accounting equation to complex valuation ratios, each concept builds on previous knowledge.

The math behind money follows logical patterns. Assets minus liabilities equals equity. Revenue minus expenses equals profit. Current assets divided by current liabilities reveal liquidity. These relationships don’t change based on market conditions or economic cycles.

Financial literacy creates options. It enables evaluation of job offers, investment opportunities, and business ventures using data rather than hope. It reveals when debt accelerates wealth building and when it creates dangerous risk.

The definitions above form a foundation. The next step: apply them. Read a balance sheet. Calculate financial ratios. Compare investment options using evidence-based metrics.

Financial knowledge compounds like interest; each new concept multiplies understanding of previous ones. Small improvements in financial literacy generate outsized returns over time through better decisions, avoided mistakes, and recognized opportunities.

Start with the basics. Master the core concepts. Build systematically. The vocabulary of finance becomes fluent through practice, and fluency creates wealth-building capability.

Next Steps:

- Review one financial statement this week using the definitions above

- Calculate three financial ratios for a company you’re interested in

- Apply one budgeting rule to your personal finances

- Learn one new financial concept from our related guides

- Track your progress as financial literacy grows

The journey from financial confusion to confidence starts with simple definitions. This Finance cheat sheet provides the roadmap. The destination, financial literacy and wealth-building capability, awaits those who commit to understanding the math behind money.

📊 Financial Ratio Calculator

Calculate key financial ratios instantly with your data

Your Result:

Interpretation:

References

[1] Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) – Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP)

[2] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission – “Beginners’ Guide to Financial Statements”

[3] CFA Institute – “Financial Statement Analysis”

[4] Federal Reserve – “Financial Accounts of the United States”

[5] Investopedia – “Financial Ratios”

[6] Morningstar – “Understanding Financial Statements”

[7] American Institute of CPAs (AICPA) – Accounting Standards and Guidelines

About the Author

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that explains the math behind money with precision and clarity. With expertise in financial analysis, valuation principles, and evidence-based investing, Max translates complex financial concepts into actionable insights for beginner and intermediate investors. His approach combines analytical rigor with educational warmth, helping readers build financial literacy through understanding cause-and-effect relationships in money management.

Educational Disclaimer

This article provides educational information about financial concepts and definitions. It does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. Financial decisions should be based on individual circumstances, risk tolerance, and goals. Consult qualified financial professionals before making significant financial decisions. Past performance does not guarantee future results. All investments carry risk, including potential loss of principal. The Rich Guy Math provides educational content to improve financial literacy, not personalized financial recommendations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Finance Cheat Sheet and why do beginners need one?

A Finance Cheat Sheet provides simple definitions of essential financial terms and concepts in one accessible reference. Beginners need this because financial literacy starts with understanding basic vocabulary—terms like assets, liabilities, equity, and financial ratios. Without these foundational definitions, reading financial statements, evaluating investments, or making informed money decisions becomes impossible. A cheat sheet removes the intimidation factor and provides quick reference for core concepts.

What are the three most important financial statements to understand?

The three essential financial statements are the Balance Sheet (showing financial position at a specific moment), the Income Statement (revealing profitability over a period), and the Cash Flow Statement (tracking actual cash movement through operating, investing, and financing activities). Together, these statements provide a complete picture of financial health.

How do liquidity ratios differ from profitability ratios?

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to pay short-term obligations, answering “Can you pay your bills?” Profitability ratios measure how effectively a business generates profit, answering “Are you making money?” Liquidity focuses on short-term survival, while profitability focuses on long-term performance.

What’s the difference between accounting profit and economic profit?

Accounting profit follows GAAP and equals revenue minus explicit costs. Economic profit subtracts both explicit costs and opportunity costs. A business can show positive accounting profit while generating negative economic profit, meaning it’s destroying shareholder value.

How does compound interest differ from simple interest?

Simple interest is earned only on the original principal. Compound interest is earned on principal plus accumulated interest, creating exponential long-term growth. Over decades, compounding dramatically increases wealth compared to simple interest.

What financial ratios should beginners focus on first?

Beginners should start with the Current Ratio (liquidity), Net Profit Margin (profitability), and Debt-to-Equity Ratio (solvency). These provide a quick snapshot of financial strength. After learning the basics, expand into ROE and the Quick Ratio.

How can I use this Finance Cheat Sheet to make better money decisions?

Use the definitions to evaluate your own finances: analyze liquidity for emergency planning, apply compound interest when comparing savings options, and use ratios to assess business opportunities. The cheat sheet helps you compare alternatives and make evidence-based decisions.

What’s the relationship between the accounting equation and the balance sheet?

The accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) is the foundation of the balance sheet. Assets appear on one side, and liabilities plus equity appear on the other. They must always balance because every asset is financed by either debt or equity.