A credit line is a flexible borrowing option that lets you access money up to a preset limit, repay what you use, and borrow again without reapplying. Unlike a traditional loan that gives you a lump sum upfront, a credit line allows ongoing access to funds, making it useful for managing cash flow, covering short-term expenses, or handling financial emergencies. Credit lines are commonly offered by banks, credit unions, and lenders in forms like personal lines of credit, business credit lines, and home equity lines of credit (HELOCs).

This article is part of our complete Credit Cards Guide, where we break down APRs, interest, rewards, fees, and how to use credit cards the smart way.

This guide breaks down the mechanics, mathematics, and strategic applications of credit lines with the precision needed to make evidence-based borrowing decisions.

Key Takeaways

A credit line is revolving credit that allows repeated borrowing and repayment up to a preset limit during a draw period, then requires full repayment during a separate repayment period

Interest accrues only on borrowed amounts, making credit lines more cost-efficient than loans when funds aren’t needed immediately or continuously

Variable APRs create rate risk—monthly costs can increase when the Federal Reserve raises benchmark rates, affecting budgeting predictability

Credit utilization impacts credit scores—keeping borrowed amounts below 30% of the credit limit protects creditworthiness and borrowing costs

Strategic use cases include emergency funds, business working capital, and short-term cash flow gaps—not ongoing expenses or discretionary purchases

What Is a Credit Line?

A credit line (also called a line of credit or LOC) is a flexible borrowing arrangement that provides access to funds up to a predetermined limit without requiring a new loan application each time money is needed.

Unlike a traditional loan that disburses the full amount upfront, a credit line functions as revolving credit. Borrowers draw only what they need, when they need it, and pay interest exclusively on the outstanding balance, not the entire credit limit.

Key Features That Define Credit Lines

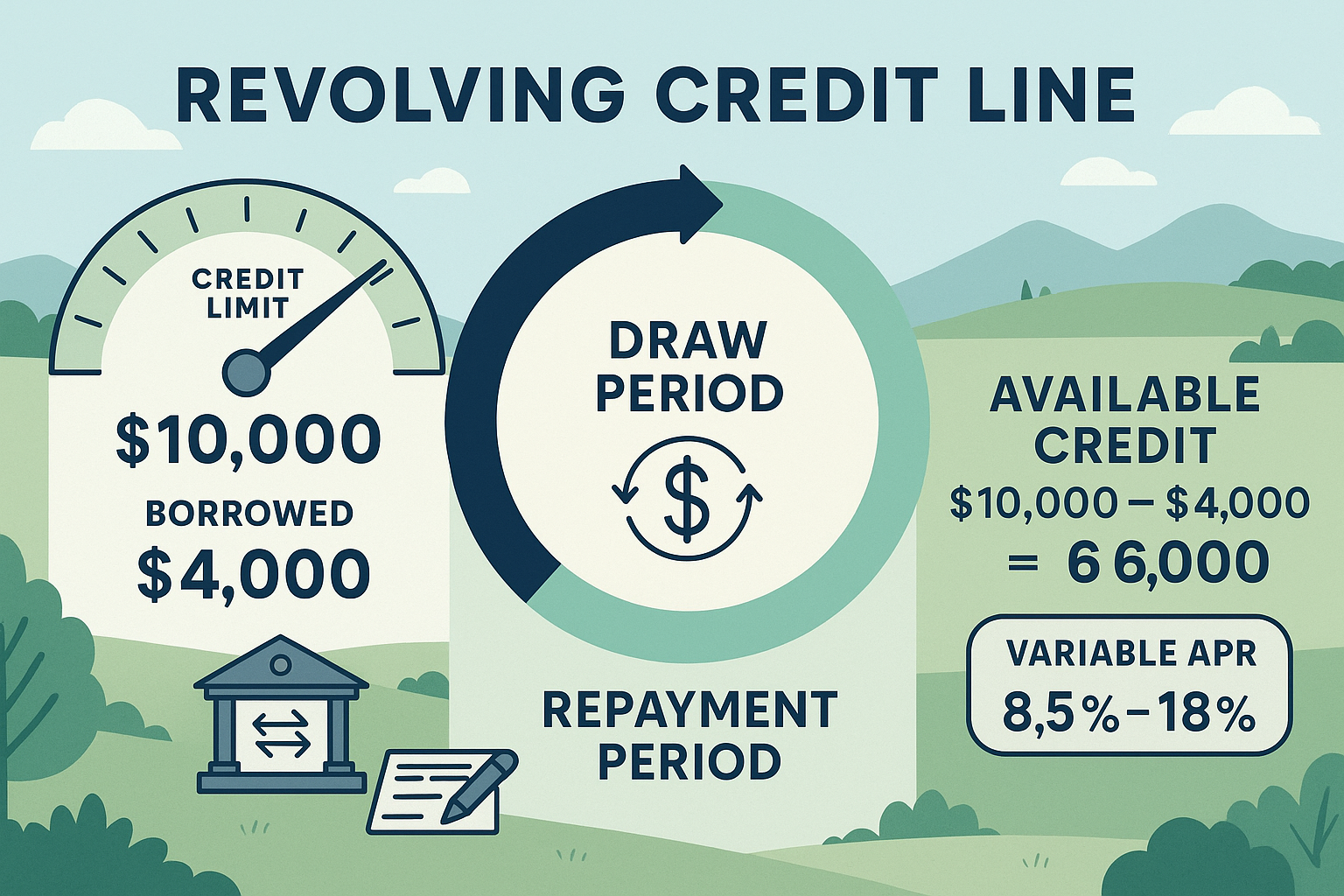

Credit Limit: The maximum amount available to borrow, determined by the lender based on creditworthiness, income, debt-to-income ratio, and sometimes collateral value.

Revolving Balance: As borrowed funds get repaid during the draw period, that credit becomes available again for future use, similar to how credit cards operate.

Variable APR: Most credit lines carry interest rates tied to benchmark rates like the Prime Rate, meaning monthly costs fluctuate with Federal Reserve policy changes.

Draw and Repayment Periods: Credit lines operate in two distinct phases, an initial draw period (typically 5-10 years) when borrowing and minimum payments occur, followed by a repayment period when no new borrowing is allowed, and the remaining balance must be paid in full through fixed installments.

Credit Line vs Credit Limit

These terms often get confused, but they represent different concepts:

- Credit Line = The financial product itself (the account and borrowing arrangement)

- Credit Limit = The maximum dollar amount available within that credit line

A $20,000 credit line has a $20,000 credit limit. If $7,000 is currently borrowed, the available credit is $13,000. Understanding this distinction matters for credit utilization calculations that affect credit scores.

Insight: Credit lines provide optionality; the ability to access capital when opportunity or necessity demands it, without paying interest on unused funds. This structural advantage makes them valuable for managing uncertainty.

How a Credit Line Works

The mechanics of credit lines follow a two-phase lifecycle that determines both flexibility and eventual repayment obligations.

Draw Periods and Repayment

Draw Period (Years 1-5 or 1-10 depending on terms):

During this phase, borrowers can:

- Withdraw any amount up to the credit limit

- Make minimum monthly payments (typically interest-only or a small percentage of the balance)

- Repay borrowed amounts in any size, as long as minimums are met

- Re-borrow repaid funds, maintaining revolving access

Repayment Period (Years 6-15 or 11-20):

Once the draw period ends:

- No additional borrowing is permitted

- The entire remaining balance converts to a fixed amortization schedule

- Equal monthly payments (principal + interest) are required until the balance reaches zero

- The account closes after full repayment

This structure differs significantly from credit cards, which typically remain open indefinitely as long as the account stays active and in good standing.

Interest Accrual and Variable Rates

Interest on credit lines accrues daily based on the outstanding balance and the current APR.

The daily interest formula:

Daily Interest = (Outstanding Balance × APR) ÷ 365

For example, with a $5,000 balance at 12% APR:

Daily Interest = ($5,000 × 0.12) ÷ 365 = $1.64 per day

Monthly Interest ≈ $1.64 × 30 = $49.20

Because most credit lines carry variable APRs tied to the Prime Rate, this cost changes when the Federal Reserve adjusts interest rates. A 0.25% rate increase on a $10,000 balance adds approximately $25 annually in interest costs—seemingly small, but compounding over years[3].

Example Calculation (With Math)

Scenario: $15,000 credit line at Prime + 4% (currently 12.5% APR)

Month 1: Borrow $6,000 for emergency home repair

- Outstanding Balance: $6,000

- Daily Interest: ($6,000 × 0.125) ÷ 365 = $2.05

- Month 1 Interest: $2.05 × 30 = $61.50

- Minimum Payment (interest-only): $61.50

Month 2: Pay $500 toward principal

- New Balance: $6,000 – $500 = $5,500

- Daily Interest: ($5,500 × 0.125) ÷ 365 = $1.88

- Month 2 Interest: $1.88 × 30 = $56.44

- Available Credit: $15,000 – $5,500 = $9,500 (revolving access restored)

Month 3: Borrow an additional $2,000 for business inventory

- New Balance: $5,500 + $2,000 = $7,500

- Daily Interest: ($7,500 × 0.125) ÷ 365 = $2.57

- Month 3 Interest: $2.57 × 30 = $77.05

This revolving structure means each borrowing and repayment decision directly changes the interest cost, a mathematical relationship that rewards disciplined use and punishes carrying high balances.

Takeaway: Interest costs on credit lines are variable in two dimensions—the balance owed and the APR charged. Both factors must be managed to control total borrowing costs.

Types of Credit Lines

Credit lines come in several forms, each designed for specific use cases and backed by different collateral structures.

Personal Credit Line

Personal lines of credit (PLOCs) are unsecured or secured borrowing arrangements for individual consumers.

- Unsecured PLOCs: No collateral required; qualification based purely on credit score (typically 680+), income, and debt-to-income ratio

- Secured PLOCs: Backed by collateral like a certificate of deposit or savings account, offering lower APRs (often 6-12% vs 15-25% for unsecured)

- Typical Limits: $1,000 – $50,000 depending on creditworthiness

- Access Method: Bank transfers or dedicated checkbook (no physical card)

PLOCs work well for consolidating higher-interest debt, covering irregular expenses, or maintaining an emergency fund alternative that doesn’t lock capital in low-yield savings accounts.

Credit Card Line

Credit cards are technically revolving credit lines with these distinctions:

- Indefinite draw period (no forced repayment period unless the account closes)

- Physical card for point-of-sale purchases

- Higher APRs (typically 18-29%)

- Rewards programs and consumer protections

- Minimum payments often cover only 1-3% of the balance plus interest

While convenient, credit cards carry the highest borrowing costs among credit line types. Understanding APY vs APR helps calculate the true annual cost when balances carry month-to-month.

Business Line of Credit

Business LOCs provide working capital for operational expenses, inventory purchases, and cash flow gaps.

- Limits: $10,000 – $500,000+, depending on business revenue and credit profile

- Collateral: Can be secured (equipment, receivables, real estate) or unsecured

- APR Range: 7-25% based on business creditworthiness

- Use Cases: Seasonal inventory, accounts payable timing gaps, bridging accounts receivable delays

Business credit lines excel when revenue timing doesn’t align with expense timing, a common challenge in businesses with 30-60 day payment terms from customers but immediate supplier payment requirements.

Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC)

HELOCs are secured credit lines backed by home equity.

Credit Limit Formula:

HELOC Limit = (Home Value × LTV Ratio) – Existing Mortgage Balance

For a $400,000 home with $250,000 mortgage balance at 85% LTV:

HELOC Limit = ($400,000 × 0.85) – $250,000 = $90,000

Key Features:

- APRs typically 6-10% (lower than unsecured options)

- Draw periods: 5-10 years

- Repayment periods: 10-20 years

- Risk: Home serves as collateral; default can result in foreclosure

HELOCs make sense for major home improvements that increase property value, debt consolidation at lower rates, or large planned expenses. They should not be used for discretionary spending or depreciating purchases.

Securities-Backed Line of Credit (SBLOC)

Portfolio lines or SBLOCs are secured by investment portfolios (stocks, bonds, ETFs).

- Limits: Typically 50-70% of portfolio value

- APRs: Often Prime + 1-3% (currently 9-11%)

- No Credit Check: Qualification based on portfolio value, not credit score

- Tax Advantage: Borrowing doesn’t trigger capital gains taxes (unlike selling investments)

Risk: Market downturns can trigger margin calls requiring immediate repayment or additional collateral. If the portfolio value drops below the maintenance threshold, the lender may liquidate securities to cover the loan.

SBLOCs work for high-net-worth individuals who need liquidity without disrupting long-term investment strategies, but they require a sophisticated understanding of risk management and market volatility.

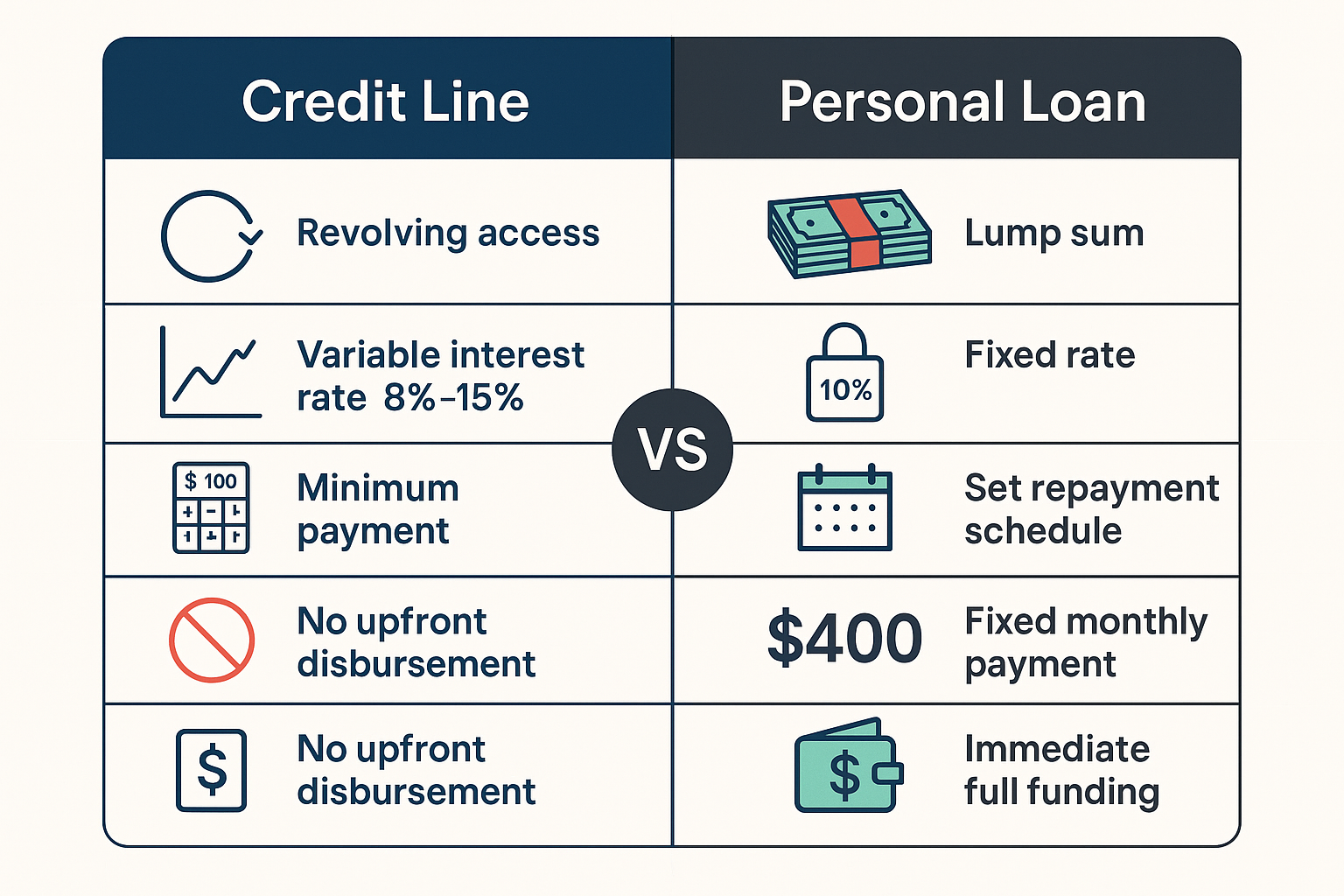

Credit Line vs Loan: Key Differences

Understanding when to use a credit line versus a traditional personal loan requires comparing their structural differences.

| Feature | Credit Line | Personal Loan |

|---|---|---|

| Disbursement | Only on the borrowed amount | Lump sum upfront |

| Interest | On the entire loan amount | High during the draw period |

| Payment Structure | Variable (based on balance) | Fixed monthly payment |

| APR Type | Usually variable | Usually fixed |

| Repayment Flexibility | High during draw period | None, fixed schedule |

| Access After Repayment | Revolving (can borrow again) | Closed after payoff |

| Best For | Uncertain timing/amount | Known expense amount |

| Typical APR Range | 8-25% | 6-36% |

Decision Framework:

Choose a Credit Line when:

- The exact amount needed is uncertain

- Expenses occur irregularly over time

- Flexibility to re-borrow is valuable

- Only short-term borrowing is anticipated

Choose a Personal Loan when:

- The expense amount is known and fixed

- Budget predictability (fixed payments) is a priority

- A lower fixed APR is available

- No future borrowing is needed

For major one-time expenses like debt consolidation, personal loans often provide better cost certainty. For ongoing business operations or emergency fund backup, credit lines offer superior flexibility.

Pros and Cons of a Credit Line

Advantages

1. Pay Interest Only on What You Use

Unlike loans that charge interest on the full amount from day one, credit lines accrue interest exclusively on the outstanding balance. If a $20,000 credit line sits unused, the interest cost is $0.

2. Revolving Access During Draw Period

Repaying borrowed funds restores available credit, creating a self-replenishing emergency fund or working capital source without repeated applications.

3. Lower APRs Than Credit Cards

Personal credit lines typically carry APRs 5-10 percentage points below credit cards, reducing interest costs significantly for the same borrowed amount[4].

4. Flexible Repayment (During Draw Period)

Minimum payments keep the account current, but larger payments reduce principal faster—allowing borrowers to match repayment to cash flow.

5. No Prepayment Penalties

Most credit lines allow full early repayment without fees, unlike some loans that charge penalties for paying off principal ahead of schedule.

Disadvantages

1. Variable APR Risk

When the Federal Reserve raises rates, credit line costs increase automatically. A 2% rate increase on a $15,000 balance adds $300 annually in interest—a cost that compounds if balances remain high.

2. Temptation to Overborrow

Easy access to funds can encourage spending beyond necessity, particularly when minimum payments feel manageable but principal balances grow.

3. Forced Repayment Period

Once the draw period ends, the entire balance must be repaid through fixed payments—potentially creating budget stress if large balances remain.

4. Credit Score Impact

High credit utilization (borrowed amount ÷ credit limit) can lower credit scores, increasing costs on future borrowing.

5. Collateral Risk (Secured Lines)

HELOCs and SBLOCs put assets at risk. Market downturns or missed payments can result in foreclosure or forced liquidation of investments.

6. Fees

Some credit lines charge annual maintenance fees ($25-75), draw fees, or inactivity fees that add to total borrowing costs.

Insight: Credit lines are powerful tools for those with discipline and clear use cases. For those prone to lifestyle inflation or impulse spending, the flexibility becomes a liability rather than an asset.

How to Qualify for a Credit Line

Lenders evaluate credit line applications using several key metrics that determine both approval and the credit limit offered.

Credit Score Ranges

Minimum Scores by Product Type:

- Unsecured Personal Credit Line: 680-700+

- Secured Personal Credit Line: 620-660+

- HELOC: 620-680+ (plus 15-20% home equity)

- Business Line of Credit: 650+ business credit score

- SBLOC: No minimum (portfolio value determines qualification)

Higher credit scores unlock better APRs. A 760+ score might qualify for Prime + 2% (currently ~10.5%), while a 680 score might receive Prime + 8% (~16.5%)—a difference of $900 annually on a $15,000 average balance[5].

Understanding how to build and maintain a strong credit score directly impacts borrowing costs across all credit products.

Income and Debt-to-Income Ratio (DTI)

Lenders verify income stability and calculate:

DTI Ratio = Total Monthly Debt Payments ÷ Gross Monthly Income

Example:

- Gross Monthly Income: $6,000

- Existing Debts: $1,200 (car loan) + $300 (student loan) + $200 (credit cards) = $1,700

- DTI = $1,700 ÷ $6,000 = 28.3%

Qualification Thresholds:

- Below 36%: Strong approval likelihood

- 36-43%: Possible approval with a strong credit score

- Above 43%: Difficult to qualify for unsecured credit lines

Reducing existing debt before applying improves approval odds and increases the credit limit offered.

Bank Relationship and Collateral

Existing Banking Relationships can improve terms:

- Current checking/savings accounts with the lender

- Direct deposit history

- Previous loan repayment performance

Collateral Options (for secured lines):

- Home equity (HELOCs)

- Investment portfolios (SBLOCs)

- Certificates of deposit

- Business assets (equipment, inventory, receivables)

Secured credit lines typically offer:

- 3-8 percentage points lower APRs

- Higher credit limits (often 50-90% of collateral value)

- Easier approval for lower credit scores

The trade-off: collateral risk. Defaulting on a secured line can result in asset seizure, foreclosure, or forced liquidation—consequences that extend beyond credit score damage.

Credit Line and Your Credit Score

Credit lines affect credit scores through three primary mechanisms, each with a different mathematical weight in FICO scoring models.

Credit Utilization (30% of FICO Score)

Utilization Ratio = Outstanding Balance ÷ Credit Limit

This ratio applies both per-account and across all revolving credit.

Example:

- Credit Line Limit: $20,000

- Current Balance: $8,000

- Utilization: $8,000 ÷ $20,000 = 40%

Score Impact Thresholds:

- Below 10%: Optimal minimal score impact

- 10-30%: Good, slight score benefit

- 30-50%: Moderate damage scores may drop 10-30 points

- Above 50%: Significant damage scores may drop 30-80+ points

Maintaining utilization below 30% across all revolving accounts protects creditworthiness. For detailed strategies, see our guide on credit utilization.

Mathematical Example:

Opening a $15,000 credit line while carrying $3,000 on existing credit cards with $10,000 total limits:

Before: $3,000 ÷ $10,000 = 30% utilization

After: $3,000 ÷ $25,000 = 12% utilization

This reduction can increase credit scores by 15-40 points, even without paying down any debt, simply by increasing available credit.

Hard Inquiries (10% of FICO Score)

Applying for a credit line triggers a hard inquiry (hard pull) that:

- Appears on credit reports for 24 months

- Affects scores for 12 months

- Typically reduces scores by 5-10 points temporarily

Multiple inquiries within 14-45 days (depending on scoring model) for the same product type count as a single inquiry, but this “shopping window” applies to mortgages and auto loans, not credit lines or credit cards.

Strategic Timing: Avoid applying for multiple credit lines within short periods. Space applications at least 6 months apart to minimize score impact.

Reporting Cycles and Payment History (35% of FICO Score)

Credit line activity reports to bureaus monthly, typically on the statement closing date—not the payment due date.

Key Insight: The balance reported is whatever amount is outstanding on the closing date, regardless of whether it gets paid in full before the due date.

Strategy: Make payments before the statement closing date to report lower balances and maintain low utilization ratios.

Payment History Impact:

- On-time payments: Positive history builds over time

- 30+ days late: Score drop of 60-110 points

- 60+ days late: Score drop of 70-135 points

- Default/charge-off: Score drop of 100-150+ points

Even a single missed payment can devastate creditworthiness for 7 years. Setting up automatic minimum payments prevents this catastrophic risk.

When a Credit Line Is a Smart Financial Tool

Credit lines serve specific strategic purposes, not general spending needs.

Emergency Fund Backup

Rather than keeping $20,000 in a 0.5% savings account, some strategists maintain $5,000 in liquid savings plus a $15,000 credit line as backup.

Math Comparison (5-year period):

Option A: $20,000 in savings at 0.5% APY

- Interest Earned: $20,000 × (1.005)^5 = $504

Option B: $5,000 in savings + $15,000 invested at 8% average return + $15,000 credit line (unused)

- Savings Interest: $5,000 × (1.005)^5 = $126

- Investment Growth: $15,000 × (1.08)^5 = $22,039 (gain of $7,039)

- Credit Line Cost (if unused): $0

- Net Advantage: $7,039 – $504 = $6,535

If an emergency requires $10,000 in year 3:

- Borrow $10,000 at 12% APR for 6 months

- Interest Cost: ~$600

- Investment remains intact, continuing to compound

- Repay from income over 6 months

This approach requires discipline and a stable income, but mathematically optimizes capital efficiency. For more on emergency fund strategies, see the 50/30/20 rule.

Business Working Capital Management

Scenario: Seasonal retail business with $50,000 monthly revenue, but $30,000 inventory purchase is required 90 days before peak season.

Without Credit Line:

- Must accumulate $30,000 cash, delaying growth

- Opportunity cost of capital sitting idle

- May miss optimal inventory pricing

With $40,000 Business Line of Credit:

- Draw $30,000 for inventory (Month 1)

- Interest for 90 days at 15% APR: ~$1,125

- Revenue from inventory: $75,000 (Month 4)

- Gross Profit: $75,000 – $30,000 – $1,125 = $43,875

- ROI: 146% on the $30,000 investment

The credit line enables revenue that wouldn’t exist otherwise—classic strategic use of debt financing.

Short-Term Cash Flow Gaps

Individual Example: Annual bonus of $15,000 arrives in December, but $8,000 tax bill is due in April.

Rather than selling investments and triggering capital gains taxes, borrow $8,000 on a credit line for 8 months:

- Interest at 10% APR: ~$533

- Investments continue compounding

- Repay from bonus in December

Business Example: Accounts receivable of $25,000 due in 45 days, but payroll of $20,000 is due now.

Credit line bridges the gap without disrupting operations or delaying vendor payments that might damage relationships.

When NOT to Use a Credit Line

Poor Use Cases:

- Ongoing lifestyle expenses beyond income

- Discretionary purchases (vacations, electronics, furniture)

- Speculative investments without a clear ROI

- Debt consolidation without addressing spending behavior

- Down payments on depreciating assets (vehicles, boats)

Credit lines amplify both good and bad financial decisions. Used strategically for short-term gaps with clear repayment paths, they preserve wealth. Used for consumption or lifestyle inflation, they accelerate wealth destruction through compounding interest.

Risks to Watch Out For

Rate Reset Exposure

Variable APR Mechanics:

Most credit lines tie rates to the Prime Rate, which tracks the Federal Reserve’s federal funds rate.

Historical Example (2022-2023):

- January 2022: Prime Rate = 3.25%

- December 2023: Prime Rate = 8.50%

- Increase: 5.25 percentage points

For a credit line at Prime + 4%:

- January 2022 APR: 7.25%

- December 2023 APR: 12.50%

Impact on $15,000 Balance:

- 2022 Annual Interest: $15,000 × 0.0725 = $1,088

- 2023 Annual Interest: $15,000 × 0.1250 = $1,875

- Increase: $787 annually (72% higher cost)

This risk intensifies during Federal Reserve tightening cycles. Borrowers must budget for potential rate increases or face payment shock when costs jump.

Mitigation Strategy: Consider converting to a fixed-rate personal loan if rates are expected to rise and a large balance will be carried long-term.

Over-Borrowing and Minimum Payment Trap

Scenario: $20,000 credit line with 2% minimum payment requirement

Month 1: Borrow $15,000 at 14% APR

- Minimum Payment: $15,000 × 0.02 = $300

- Interest Portion: $15,000 × 0.14 ÷ 12 = $175

- Principal Reduction: $300 – $175 = $125

At this pace:

- Time to Pay Off: 126 months (10.5 years)

- Total Interest Paid: $22,750

- Total Cost: $37,750 for $15,000 borrowed

Making only minimum payments during the draw period creates a debt spiral where principal barely decreases, interest compounds, and the repayment period arrives with a massive balance requiring large fixed payments.

Solution: Treat credit lines like short-term tools (6-24 months), not long-term financing. Aggressive principal payments during the draw period prevent this trap.

Collateral Risk (HELOC and SBLOC)

HELOC Foreclosure Risk:

Missing payments on a home equity line can result in foreclosure, losing the home entirely, not just the borrowed amount.

Example:

- Home Value: $500,000

- Mortgage Balance: $300,000

- HELOC Balance: $60,000

- Default on HELOC → Foreclosure → Loss of $200,000 equity

The risk-to-reward ratio makes HELOCs dangerous for discretionary spending or speculative uses.

SBLOC Margin Call Risk:

Scenario:

- Portfolio Value: $200,000

- SBLOC Limit: 50% = $100,000

- Borrowed Amount: $80,000

- Maintenance Threshold: 60% (balance must stay below 60% of portfolio value)

Market Correction:

- Portfolio drops 30% to $140,000

- New 60% Threshold: $140,000 × 0.60 = $84,000

- Current Balance: $80,000

- Margin Call: Must deposit $20,000 cash or securities, or the lender liquidates portfolio assets

During the 2008 financial crisis, many investors faced forced liquidation of investments at market bottoms, crystallizing losses that would have recovered over time.

Risk Management: Never borrow more than 30-40% of portfolio value on SBLOCs, and maintain cash reserves to meet potential margin calls without forced selling.

Case Studies: Credit Lines in Action

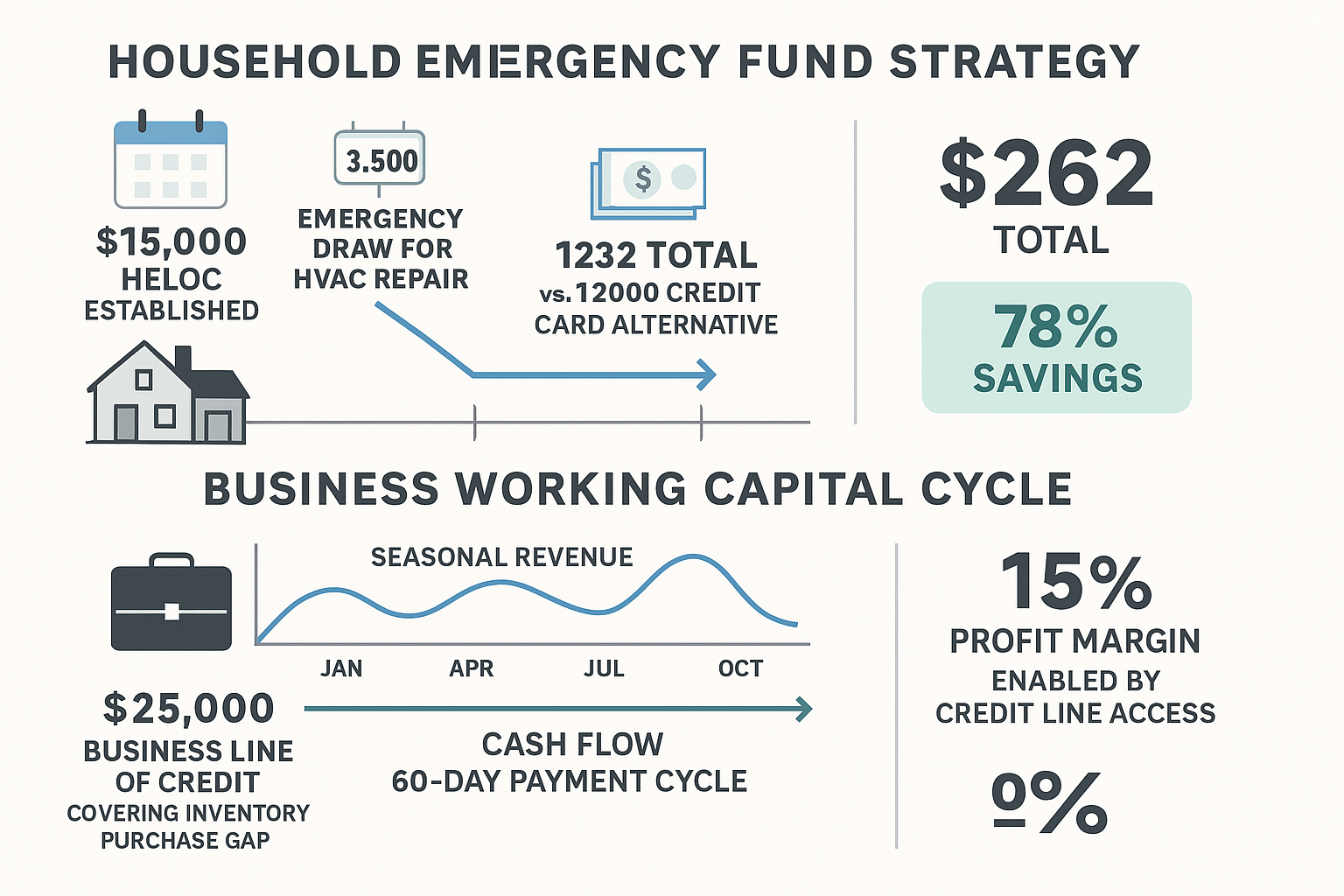

Case Study 1: Household Emergency Fund Strategy

Profile:

- Household Income: $95,000 annually

- Monthly Expenses: $5,500

- Traditional Emergency Fund Target: 6 months = $33,000

- Current Savings: $12,000

Strategy: Establish $25,000 unsecured personal credit line at 11% APR as an emergency backup

Year 2 Emergency: HVAC system failure requiring $6,500 repair

Decision Tree:

Option A: Deplete savings entirely

- Remaining Savings: $12,000 – $6,500 = $5,500

- Emergency fund severely compromised

- Psychological stress of low reserves

Option B: Charge to credit card at 22% APR

- Monthly Interest: $6,500 × 0.22 ÷ 12 = $119

- If paid over 12 months: Total interest = ~$780

Option C: Draw from credit line at 11% APR

- Monthly Interest: $6,500 × 0.11 ÷ 12 = $60

- Repay $550/month for 12 months

- Total Interest: ~$390

- Savings vs Credit Card: $390 in interest saved

Outcome:

- Emergency handled immediately

- Savings remain intact for additional emergencies

- Lower interest cost than the credit card alternative

- Credit line available credit: $25,000 – $6,500 = $18,500 (still accessible)

Repayment: Over 12 months, $550 monthly payments fully repay the $6,500 plus interest, and the full $25,000 credit line is restored for future needs.

This demonstrates strategic use, short-term borrowing for a genuine emergency, with a clear repayment plan that costs less than alternatives.

Case Study 2: Business Working Capital Cycle

Profile:

- Small Manufacturing Business

- Annual Revenue: $800,000

- Seasonal Pattern: 60% of revenue in Q4 (holiday season)

- Challenge: Must purchase $45,000 in raw materials in August for October-December production

Cash Flow Gap:

- August Cash Available: $15,000

- Materials Needed: $45,000

- Shortfall: $30,000

Traditional Options:

- Delay production → Miss peak season → Revenue loss

- Term loan → Pay interest on the full $30,000 for 12+ months

- Factor receivables → Pay 3-5% fees on future invoices

Credit Line Solution: $50,000 business line of credit at 13% APR

Timeline:

August (Month 1):

- Draw $30,000 for materials

- Interest: $30,000 × 0.13 ÷ 12 = $325

September (Month 2):

- Production occurs

- Interest: $325

- No revenue yet

October (Month 3):

- Revenue: $80,000

- COGS: $45,000 (materials + labor)

- Gross Profit: $35,000

- Pay down credit line: $15,000

- Remaining Balance: $15,000

- Interest: $162.50

November (Month 4):

- Revenue: $120,000

- Pay down credit line: $15,000 (full repayment)

- Interest: $162.50

- Total Interest Paid: $975

Financial Outcome:

- Revenue Enabled: $200,000 (that wouldn’t exist without materials)

- Gross Profit: $70,000

- Interest Cost: $975

- Net Benefit: $69,025

ROI Calculation:

- Investment: $30,000 (borrowed capital)

- Return: $70,000 (gross profit)

- ROI: ($70,000 – $30,000) ÷ $30,000 = 133%

The credit line enabled revenue generation that exceeded the cost of capital by orders of magnitude—classic strategic debt financing that accelerates business growth.

Key Success Factors:

- Clear revenue timeline (seasonal predictability)

- Defined repayment source (Q4 revenue)

- Short borrowing duration (4 months)

- High ROI relative to interest cost

This contrasts sharply with using credit lines for operating losses or ongoing expenses—scenarios where no repayment source exists and debt compounds indefinitely.

💳 Credit Line Interest Calculator

Calculate your monthly and total interest costs across different scenarios

Conclusion

A credit line is neither inherently good nor bad—its value depends entirely on the mathematical relationship between borrowing cost, alternative options, and the return generated or preserved through its use.

The math behind smart credit line use:

Borrow only when the cost of capital is less than the opportunity cost of alternatives (selling investments, depleting emergency savings, missing revenue opportunities)

Maintain utilization below 30% to protect credit scores and preserve future borrowing capacity at favorable rates

Plan repayment before borrowing—every draw should have a defined repayment timeline and source

Monitor variable APR exposure—rate increases can transform affordable borrowing into financial stress

Understand collateral risk—secured lines offer lower rates but put assets at risk during market volatility or payment difficulties

Credit lines serve as financial optionality—the ability to access capital when opportunity or necessity demands it, without paying for unused capacity. This structural advantage makes them valuable for managing uncertainty in both personal and business finance.

But optionality becomes liability when it enables overconsumption, speculative risk-taking, or lifestyle inflation beyond income capacity. The difference between wealth preservation and wealth destruction often lies in whether credit lines are used strategically (short-term, high-ROI applications) or tactually (funding ongoing consumption).

Next Steps:

- Assess your need: Do you have irregular cash flow gaps, emergency fund backup needs, or business working capital cycles that justify a credit line?

- Calculate your qualification: Check your credit score, calculate your DTI ratio, and determine likely APR ranges

- Compare products: Evaluate personal lines, HELOCs, business lines, or SBLOCs based on your specific use case and risk tolerance

- Establish before you need it: Credit lines are easiest to obtain when you don’t urgently need them, apply during stable financial periods

- Create usage rules: Define in advance what constitutes appropriate use (emergencies, working capital, short-term gaps) versus prohibited use (lifestyle spending, speculative investments)

Understanding the mechanics, mathematics, and strategic applications of credit lines transforms them from potential financial traps into powerful tools for optimizing capital efficiency and managing uncertainty, when used with discipline and clear purpose.

References

[1] Federal Reserve. (2024). “Consumer Credit – G.19.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/

[2] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2024). “What is a line of credit?” CFPB Consumer Resources. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/

[3] Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. (2024). “Managing Credit Lines and Variable Interest Rates.” FDIC Consumer News. https://www.fdic.gov/

[4] Investopedia. (2025). “Line of Credit (LOC) Definition, Types, and Examples.” https://www.investopedia.com/

[5] MyFICO. (2024). “Credit Score Ranges and Rate Impact.” FICO Score Education. https://www.myfico.com/

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform that teaches the mathematical principles behind wealth building, investing, and risk management. With a background in financial analysis and a commitment to evidence-based investing, Max breaks down complex financial concepts into clear, actionable frameworks. His work focuses on helping individuals understand the cause-and-effect relationships that govern money, credit, and long-term wealth accumulation through rigorous analysis and transparent methodology.

Educational Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. The information presented represents general principles and examples; individual financial situations vary significantly based on income, credit profile, risk tolerance, and specific goals.

Credit lines involve borrowing costs, variable interest rate risk, and potential collateral risk (for secured lines). Past performance of strategies or historical rate environments does not guarantee future results. Interest rates, credit terms, and qualification requirements change based on market conditions and individual creditworthiness.

Before applying for any credit product, consult with qualified financial advisors, tax professionals, and legal counsel who can evaluate your specific circumstances. Always read and understand credit agreements fully before signing, including all fees, rate adjustment mechanisms, draw and repayment period terms, and collateral requirements.

The Rich Guy Math and its authors are not responsible for any financial decisions made based on this content. All financial decisions carry risk and should be made after thorough research and professional consultation appropriate to your individual situation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a credit line and a credit card?

A credit line typically has a defined draw period (5–10 years) followed by a mandatory repayment period, while credit cards remain open indefinitely. Credit lines usually carry lower APRs (8–15% vs. 18–29%) and are accessed via bank transfer or checkbook rather than a physical card. Both are revolving credit, but credit lines have finite timelines and often better rates.

How does a credit line affect my credit score?

Credit lines impact scores through three mechanisms:

(1) Credit utilization: Keeping balances below 30% of the limit helps scores.

(2) Hard inquiries: Applications temporarily reduce scores by 5–10 points.

(3) Payment history: On-time payments build positive credit history, while late payments cause severe damage.

Opening a credit line can also improve scores by increasing total available credit and lowering overall utilization ratios.

Can I pay off a credit line early without penalties?

Most credit lines allow early repayment without prepayment penalties, but always verify terms before signing. Some lenders charge inactivity fees if the line isn’t used within certain periods, and a few may have minimum interest charges. Review the credit agreement for any fees related to early payoff, inactivity, or account closure.

What happens when the draw period ends on a credit line?

When the draw period ends, you can no longer borrow additional funds and the account enters the repayment period. The remaining balance converts to a fixed amortization schedule requiring equal monthly payments (principal plus interest). This transition can significantly increase monthly payments if large balances remain, so strategic paydown during the draw period is essential.

Is a HELOC or personal credit line better for emergencies?

HELOCs offer lower APRs (typically 6–10% vs. 12–18% for personal credit lines) but require your home as collateral. Personal lines carry higher rates but no collateral risk. For unpredictable emergencies, the collateral risk of HELOCs may outweigh the lower interest rate. For planned expenses with reliable repayment sources, HELOCs can provide meaningful savings. The choice depends on your risk tolerance and repayment confidence.

How much credit line should I apply for?

Apply for an amount that covers your realistic maximum need plus a 20–30% buffer, but avoid excessively large limits that may signal financial instability. For emergency funds, aim for 3–6 months of expenses. For business working capital, calculate your maximum seasonal cash flow gap. Larger limits reduce credit utilization (helping scores) but may encourage overspending—choose an amount you can responsibly manage and repay within 12–24 months if fully drawn.