When analyzing a company’s financial statements, one accounting decision can dramatically alter reported profits, tax bills, and investment valuations: the choice between FIFO and LIFO inventory methods.

This seemingly technical accounting choice creates real financial consequences. During inflationary periods, two identical companies with identical inventory can report vastly different profit margins simply because of how they account for their goods. One method might show robust earnings growth while the other appears to struggle, yet both companies sold the same products at the same prices.

Understanding FIFO vs LIFO isn’t just accounting trivia. It’s essential financial literacy for anyone serious about analyzing businesses, comparing competitors, or making evidence-based investment decisions. These inventory valuation methods directly impact the numbers investors rely on: earnings per share, profit margins, tax obligations, and balance sheet strength.

This guide breaks down the math behind these inventory accounting methods, explains when companies use each approach, and shows exactly how FIFO vs LIFO affects the financial statements investors analyze every day.

Key Takeaways

- FIFO (First-In, First-Out) assumes the oldest inventory sells first, resulting in lower cost of goods sold and higher reported profits during inflation, but creating larger tax obligations for businesses.

- LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) assumes the newest inventory sells first, producing a higher cost of goods sold and lower taxable income during inflation, offering tax advantages to U.S. companies.

- Geographic restrictions matter: LIFO is only permitted under U.S. GAAP and prohibited under IFRS, limiting its use for international companies and creating comparability challenges for investors.

- Industry selection follows logic: FIFO works best for perishable goods and time-sensitive products, while LIFO suits businesses with long-lasting inventory during inflationary environments.

- Financial statement impact is substantial: The same inventory can produce different profit margins, tax bills, and balance sheet valuations depending solely on the accounting method chosen.

What Are FIFO and LIFO? The Foundation of Inventory Accounting

Inventory accounting methods determine which costs flow from the balance sheet to the income statement when products are sold. These methods answer a deceptively simple question: when multiple units are purchased at different prices, which cost should be matched against revenue?

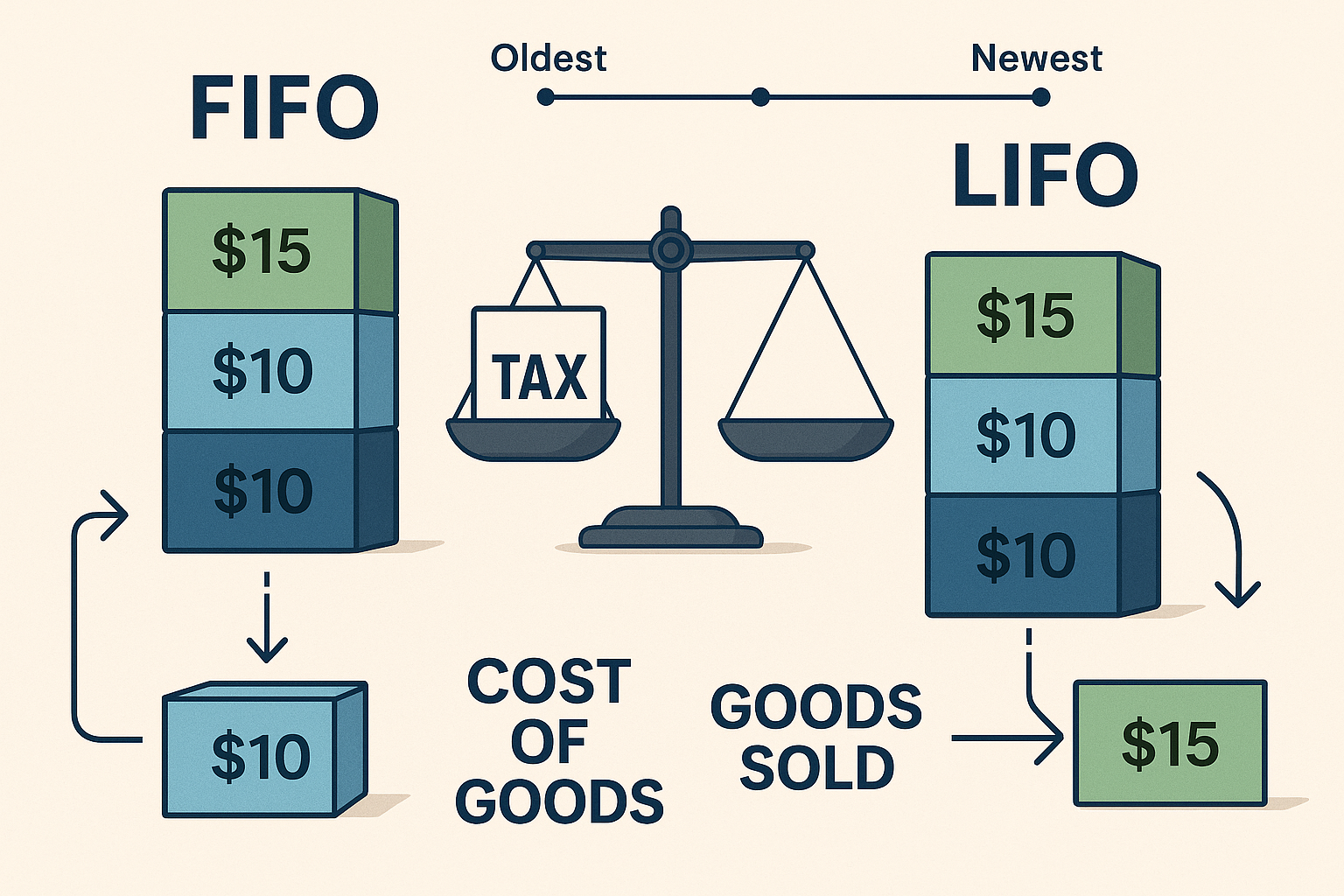

FIFO (First-In, First-Out) operates on the assumption that the oldest inventory items are sold first. The first products purchased or manufactured are the first ones removed from inventory when sales occur. This creates a natural flow where older costs move to the cost of goods sold while newer costs remain on the balance sheet as ending inventory.

LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) assumes the opposite; the newest inventory items are sold first. The most recently acquired or produced goods are the first ones matched against revenue. This means recent costs flow to the income statement while older costs stay on the balance sheet.

Neither method necessarily reflects the actual physical flow of goods. A grocery store using LIFO doesn’t literally sell the freshest milk first and save the oldest for later. These are cost flow assumptions, not descriptions of physical movement.

The distinction matters because purchase prices change over time. During inflation, newer inventory costs more than older inventory. During deflation, the reverse is true. The method chosen determines which costs are old or new, reducing reported profits.

The Four Primary Inventory Valuation Methods

While FIFO vs LIFO dominates discussions, four main inventory accounting methods exist:

- FIFO (First-In, First-Out): Oldest costs to COGS, newest costs to inventory

- LIFO (Last-In, First-Out): Newest costs to COGS, oldest costs to inventory

- Weighted Average Cost: Blends all purchase costs into a single average unit cost

- Specific Identification: Tracks each item’s actual cost

Specific Identification works for unique, high-value items like cars, jewelry, or real estate, where each unit has a serial number or distinct identifier. Weighted Average Cost simplifies calculations by averaging all costs together, moderating profit volatility.

For most businesses selling fungible goods, identical units that can’t be distinguished from each other, the choice narrows to FIFO vs LIFO. This decision shapes financial reporting, tax strategy, and how investors perceive company performance.

Understanding accounting profit requires grasping how these inventory methods alter the numbers reported on financial statements.

How FIFO Works: Oldest Inventory Out First

FIFO matches the oldest inventory costs against current revenue. When products are sold, the accounting system removes costs from inventory in chronological order, starting with the earliest purchases.

FIFO Calculation Example

Consider a retailer that purchases inventory three times during a quarter:

- January 1: 100 units at $10 each = $1,000

- February 1: 100 units at $12 each = $1,200

- March 1: 100 units at $15 each = $1,500

Total inventory: 300 units costing $3,700

During the quarter, the company sells 200 units at $25 each, generating $5,000 in revenue.

Under FIFO, the cost of goods sold calculation uses the oldest costs first:

- First 100 units sold: 100 × $10 = $1,000

- Next 100 units sold: 100 × $12 = $1,200

- Total COGS: $2,200

The remaining inventory consists of the newest purchase:

- Ending inventory: 100 units × $15 = $1,500

Gross profit = Revenue – COGS = $5,000 – $2,200 = $2,800

FIFO During Inflation

When prices rise over time, FIFO produces specific financial effects:

Lower Cost of Goods Sold: Older, cheaper costs flow to the income statement, reducing expenses.

Higher Gross Profit: Lower COGS means higher reported profit margins.

Higher Taxable Income: Greater profits result in larger tax obligations.

Higher Ending Inventory Value: Newer, more expensive costs remain on the balance sheet, inflating asset values.

This creates a balance sheet that reflects current replacement costs more accurately. The inventory shown represents recent purchase prices, closer to what the company would pay to replenish stock today.

However, the income statement may overstate true economic profit. Revenue reflects current selling prices while COGS reflects old purchase prices, a mismatch that can inflate margins beyond what’s sustainable if replacement costs have risen.

When Companies Choose FIFO

FIFO makes practical sense for businesses with:

Perishable products: Groceries, pharmaceuticals, and fresh foods naturally follow FIFO to prevent spoilage.

Fashion and seasonal goods: Clothing retailers want to sell older styles before they become outdated.

Technology products: Electronics depreciate quickly; older models must sell before they’re obsolete.

International operations: Companies reporting under IFRS must use FIFO since LIFO is prohibited.

Preference for higher reported earnings: Firms wanting to show stronger profits to shareholders often select FIFO.

The method provides better balance sheet accuracy by keeping inventory values current, though it may overstate income during inflationary periods.

How LIFO Works: Newest Inventory Out First

LIFO assumes the most recently acquired inventory is sold first. When products are sold, the accounting system matches the newest costs against revenue, leaving older costs on the balance sheet.

LIFO Calculation Example

Using the same scenario as before:

- January 1: 100 units at $10 each = $1,000

- February 1: 100 units at $12 each = $1,200

- March 1: 100 units at $15 each = $1,500

The company sells 200 units at $25 each for $5,000 in revenue.

Under LIFO, the cost of goods sold uses the newest costs first:

- First 100 units sold: 100 × $15 = $1,500

- Next 100 units sold: 100 × $12 = $1,200

- Total COGS: $2,700

The remaining inventory consists of the oldest purchase:

- Ending inventory: 100 units × $10 = $1,000

Gross profit = Revenue – COGS = $5,000 – $2,700 = $2,300

LIFO During Inflation

When prices rise, LIFO creates distinct financial outcomes:

Higher Cost of Goods Sold: Newer, more expensive costs flow to the income statement, increasing expenses.

Lower Gross Profit: Higher COGS reduces reported profit margins.

Lower Taxable Income: Smaller profits mean reduced tax obligations, the primary reason U.S. companies choose LIFO.

Lower Ending Inventory Value: Older, cheaper costs remain on the balance sheet, understating asset values.

The income statement better matches current costs against current revenue. Because COGS reflects recent purchase prices, the profit margin shown is closer to the true economic margin the company will earn going forward.

However, the balance sheet becomes distorted. Inventory values may reflect purchase prices from years or decades ago, bearing no relationship to current replacement costs. This creates what accountants call “LIFO layers”, strata of old costs that accumulate over time.

The LIFO Reserve

Companies using LIFO must disclose the LIFO reserve in financial statement notes. This figure shows the difference between inventory valued at LIFO versus what it would be under FIFO.

LIFO Reserve = FIFO Inventory Value – LIFO Inventory Value

This disclosure allows investors to adjust financial statements for comparison. Adding the LIFO reserve to inventory and subtracting it from retained earnings converts LIFO statements to approximate FIFO equivalents.

When Companies Choose LIFO

LIFO appeals to businesses with:

Non-perishable inventory: Products that don’t spoil or become obsolete can sit in inventory indefinitely.

Inflationary environments: Rising costs make LIFO’s tax benefits most valuable.

U.S.-only operations: Since LIFO is prohibited under IFRS, only domestic companies can use it without creating reporting conflicts.

Tax minimization priorities: Firms prioritizing cash flow over reported earnings prefer LIFO’s tax deferral.

Stable or growing inventory levels: Companies that maintain or increase inventory can preserve LIFO layers and tax benefits.

The method provides better income statement matching but distorts the balance sheet by understating asset values during inflation.

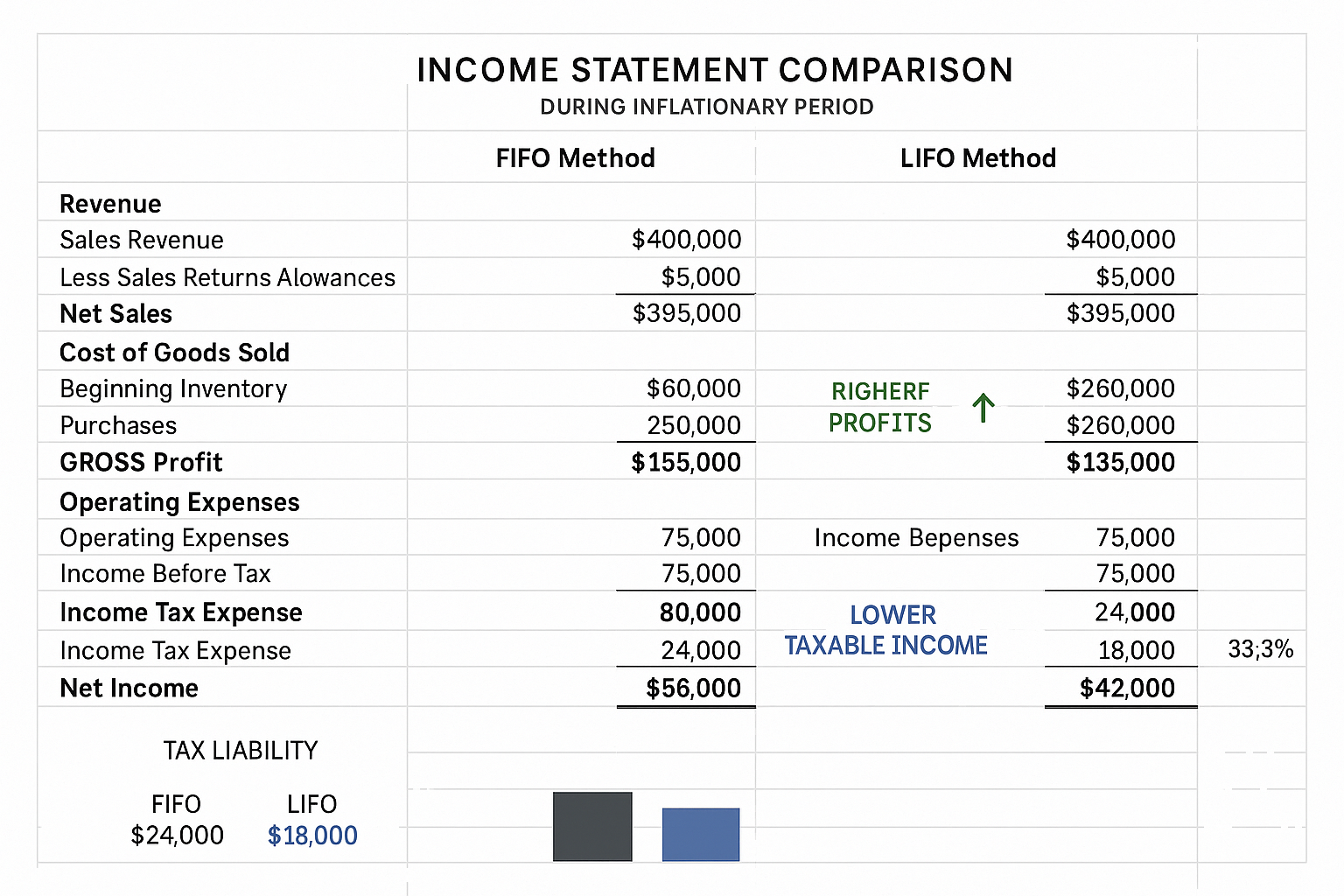

FIFO vs LIFO: Direct Comparison of Financial Impact

The choice between FIFO and LIFO creates measurable differences across financial statements. Using the same business scenario, the two methods produce divergent results.

Side-by-Side Financial Comparison

| Metric | FIFO | LIFO | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | $5,000 | $5,000 | $0 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | $2,200 | $2,700 | $500 |

| Gross Profit | $2,800 | $2,300 | $500 |

| Gross Margin | 56% | 46% | 10 percentage points |

| Ending Inventory | $1,500 | $1,000 | $500 |

| Tax (at 25%) | $700 | $575 | $125 |

| Net Income (after tax) | $2,100 | $1,725 | $375 |

The same economic activity, purchasing 300 units and selling 200, produces a $375 difference in net income purely from the accounting method chosen.

Impact on Key Financial Ratios

The FIFO vs LIFO decision cascades through financial analysis:

Profit Margins: FIFO shows higher gross and net margins during inflation, making the company appear more profitable.

Return on Assets (ROA): FIFO’s higher inventory values reduce return on assets (ROA) despite higher profits, because the denominator (assets) increases more than the numerator (income).

Inventory Turnover: LIFO’s lower inventory values increase turnover ratios, making inventory management appear more efficient.

Current Ratio: FIFO’s higher inventory values improve liquidity ratios by inflating current assets.

Earnings Per Share: FIFO produces higher EPS during inflation, potentially affecting stock valuations.

These differences aren’t accounting tricks; they’re legitimate consequences of different cost flow assumptions. Neither method is “wrong,” but they tell different stories about the same business.

Tax Implications: The Real Cash Impact

The most tangible difference between FIFO vs LIFO is tax liability. In the example above, LIFO saves $125 in taxes compared to FIFO.

This isn’t a one-time benefit. As long as inflation continues and inventory levels remain stable or grow, LIFO companies defer taxes indefinitely. The cumulative tax savings can be substantial, millions or billions of dollars for large corporations.

However, this benefit comes with strings attached. The LIFO conformity rule requires companies using LIFO for tax purposes to also use it for financial reporting. A company can’t use LIFO to minimize taxes while using FIFO to maximize reported earnings to shareholders.

If a company liquidates LIFO inventory layers, selling more than it purchases old, low-cost flows to COGS, creating a profit spike and a corresponding tax bill. This “LIFO liquidation” can produce temporary earnings boosts that don’t reflect ongoing operations.

Understanding these tax dynamics is crucial for analyzing cash flow statements and evaluating true economic performance.

Regulatory Framework: GAAP vs IFRS

The accounting rules governing FIFO vs LIFO differ dramatically between U.S. and international standards, creating complexity for global businesses and investors.

U.S. GAAP: Both Methods Permitted

Under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) used in the United States, companies can choose FIFO, LIFO, weighted average, or specific identification.

The choice is voluntary, but once made, consistency is expected. Companies switching methods must:

- Disclose the change in financial statement notes

- Justify the reason for the change

- Quantify the impact on financial results

- Apply the change retrospectively when possible

The LIFO conformity rule adds constraint: companies using LIFO for tax purposes must use it for financial reporting. This prevents companies from showing different numbers to the IRS versus investors.

IFRS: LIFO Prohibited

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), used in over 140 countries, explicitly prohibit LIFO. Only FIFO, weighted average, and specific identification are permitted.

The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) concluded that LIFO doesn’t reflect actual inventory flows and can distort financial position. The prohibition aims to improve comparability across companies and countries.

This creates challenges for multinational corporations. A U.S. company using LIFO domestically must convert to FIFO for foreign subsidiaries or consolidated IFRS statements. This dual reporting increases complexity and cost.

Implications for Investors

The regulatory divide affects investment analysis:

Comparing U.S. and international companies requires adjustments. A U.S. retailer using LIFO isn’t directly comparable to a European competitor using FIFO without normalizing for inventory method differences.

Analyzing U.S. companies requires checking which method they use. Two similar companies may show different profitability purely from accounting choices, not operational performance.

Evaluating method changes signals potential red flags. When companies switch from LIFO to FIFO, it often indicates declining inventory levels (making LIFO less beneficial) or a desire to boost reported earnings.

The LIFO reserve disclosure becomes essential for making apples-to-apples comparisons. Sophisticated investors adjust LIFO companies to FIFO equivalents before comparing financial ratios.

Industry Applications: Which Method Fits Where

Different industries gravitate toward different inventory methods based on their products, cost structures, and strategic priorities.

Industries Favoring FIFO

Grocery and Food Retail: Perishables must be sold before expiration. FIFO aligns with physical flow and prevents waste.

Pharmaceuticals: Medications have expiration dates. The oldest stock must move first to maintain efficacy and safety.

Fashion and Apparel: Clothing styles become outdated. Retailers need to clear seasonal inventory before trends change.

Technology and Electronics: Rapid innovation makes older products obsolete. Companies must sell existing inventory before new models arrive.

Automotive Parts: Some components have limited shelf life or become incompatible with newer vehicle models.

International Corporations: Companies reporting under IFRS have no choice—they must use FIFO.

These industries share common characteristics: time-sensitive products, risk of obsolescence, or international operations requiring IFRS compliance.

Industries Favoring LIFO

Oil and Gas: Petroleum products are fungible and non-perishable. Crude oil purchased years ago is identical to crude oil purchased today. LIFO’s tax benefits are substantial, given high inventory values.

Steel and Metals: Commodity products with long shelf lives and significant price volatility benefit from LIFO’s tax deferral during inflation.

Automotive Manufacturing: Car makers with large parts inventories use LIFO to reduce taxable income, though finished vehicles often use specific identification.

Wholesale Distribution: Non-perishable goods in large quantities suit LIFO, especially when replacement costs rise steadily.

Building Materials: Lumber, concrete, and construction supplies don’t spoil and experience inflationary pricing.

These industries feature non-perishable, fungible products with significant inventory investments and exposure to inflation.

The Weighted Average Alternative

Some industries prefer Weighted Average Cost (WAC), which calculates a blended average cost for all inventory units.

Formula: Total Cost of Goods Available ÷ Total Units Available = Average Cost Per Unit

WAC works well for:

- Commodities with frequent price changes: Averaging smooths volatility

- Businesses seeking simplicity: One average cost is easier than tracking layers

- Companies wanting moderate financial results: WAC falls between FIFO and LIFO

Industries like grain storage, chemical manufacturing, and some retail operations find the weighted average provides a practical middle ground.

Understanding which method competitors use is essential for meaningful industry analysis. Comparing a FIFO company to a LIFO company without adjustment distorts competitive positioning.

Practical Examples: FIFO vs LIFO in Real Scenarios

Abstract explanations only go so far. Concrete examples demonstrate how FIFO vs LIFO affects actual business results.

Example 1: Grocery Store During Inflation

Metro Foods operates a grocery chain. During Q1 2025, they purchased milk three times:

- Week 1: 1,000 gallons at $3.00 = $3,000

- Week 5: 1,000 gallons at $3.20 = $3,200

- Week 9: 1,000 gallons at $3.50 = $3,500

They sell 2,500 gallons at $5.00 each = $12,500 revenue.

Under FIFO:

- COGS: (1,000 × $3.00) + (1,000 × $3.20) + (500 × $3.50) = $7,950

- Ending inventory: 500 × $3.50 = $1,750

- Gross profit: $12,500 – $7,950 = $4,550

Under LIFO:

- COGS: (1,000 × $3.50) + (1,000 × $3.20) + (500 × $3.00) = $8,200

- Ending inventory: 500 × $3.00 = $1,500

- Gross profit: $12,500 – $8,200 = $4,300

FIFO shows $250 more profit but $250 higher inventory value. For a perishable product like milk, FIFO makes operational sense; the oldest milk should sell first. The accounting method aligns with physical reality.

Example 2: Oil Company During Inflation

Apex Energy stores crude oil. During 2025, they made three purchases:

- Q1: 10,000 barrels at $70 = $700,000

- Q2: 10,000 barrels at $75 = $750,000

- Q3: 10,000 barrels at $80 = $800,000

They sell 25,000 barrels at $95 each = $2,375,000 revenue.

Under FIFO:

- COGS: (10,000 × $70) + (10,000 × $75) + (5,000 × $80) = $1,850,000

- Ending inventory: 5,000 × $80 = $400,000

- Gross profit: $2,375,000 – $1,850,000 = $525,000

- Tax (at 25%): $131,250

Under LIFO:

- COGS: (10,000 × $80) + (10,000 × $75) + (5,000 × $70) = $1,900,000

- Ending inventory: 5,000 × $70 = $350,000

- Gross profit: $2,375,000 – $1,900,000 = $475,000

- Tax (at 25%): $118,750

LIFO saves $12,500 in taxes this year. For a commodity product with no spoilage risk, LIFO makes financial sense. The $50,000 difference in ending inventory value is artificial—crude oil from Q1 is identical to Q3 oil.

Over multiple years, these tax savings compound. If Apex maintains or grows inventory, it defers taxes indefinitely, improving cash flow for reinvestment or dividends.

Example 3: LIFO Liquidation Risk

Industrial Supply Co. has used LIFO for 20 years. Their oldest inventory layer dates to 2005 at $5 per unit. Current replacement cost is $25 per unit.

In 2025, a supply chain disruption prevents new purchases. They sell 10,000 units from old inventory layers.

COGS: 10,000 × $5 = $50,000

Revenue: 10,000 × $30 = $300,000

Gross profit: $250,000

This profit is artificially inflated. The company matched 2005 costs against 2025 revenue, creating an 83% margin that’s unsustainable. When supply normalizes and they replenish at $25 per unit, margins will collapse.

This LIFO liquidation creates:

- Temporary profit spike: Earnings jump but don’t reflect ongoing economics

- Tax bill: The company pays taxes on inflated profits

- Investor confusion: Analysts may misinterpret one-time gains as operational improvement

Companies must disclose LIFO liquidations in financial notes. Savvy investors adjust earnings to exclude these non-recurring effects.

Advantages and Disadvantages: FIFO vs LIFO

Every accounting method involves tradeoffs. Understanding the pros and cons of FIFO vs LIFO helps investors interpret financial statements and business managers make informed choices.

FIFO Advantages

Reflects Physical Flow: For most products, FIFO matches how goods actually move through inventory.

Balance Sheet Accuracy: Inventory values reflect recent purchase prices, closer to current replacement costs.

Simplicity: Easier to understand and explain to stakeholders.

International Compatibility: Permitted under both GAAP and IFRS, enabling consistent global reporting.

Higher Reported Earnings: During inflation, FIFO shows stronger profits, potentially supporting stock valuations.

Better Inventory Management: Encourages selling older stock first, reducing obsolescence risk.

FIFO Disadvantages

Higher Tax Liability: During inflation, FIFO produces larger taxable income and tax bills.

Income Statement Mismatch: Matches old costs against current revenue, potentially overstating sustainable margins.

Earnings Volatility: Profit margins fluctuate more with cost changes.

Cash Flow Impact: Higher taxes reduce cash available for reinvestment or distribution.

LIFO Advantages

Tax Deferral: During inflation, LIFO reduces taxable income and preserves cash.

Income Statement Matching: Matches current costs against current revenue, showing more realistic margins.

Inflation Hedge: Automatically adjusts COGS for price increases without manual intervention.

Cash Flow Improvement: Tax savings enhance liquidity for growth or shareholder returns.

Conservative Earnings: Lower reported profits reduce the risk of overvaluation.

LIFO Disadvantages

Balance Sheet Distortion: Inventory values can be decades old, bearing no relationship to current costs.

Complexity: LIFO layers accumulate over time, complicating record-keeping and analysis.

IFRS Prohibition: International operations can’t use LIFO, limiting the applicability for global companies.

Liquidation Risk: Selling old inventory layers creates artificial profit spikes and tax bills.

Lower Reported Earnings: During inflation, LIFO shows weaker profits, potentially depressing valuations.

Conformity Requirement: Must use LIFO for both tax and financial reporting, can’t optimize separately.

The optimal choice depends on business circumstances, industry norms, tax strategy, and reporting objectives. Neither method is universally superior.

How Inventory Methods Affect Investment Analysis

For investors analyzing companies, the FIFO vs LIFO choice creates both challenges and opportunities.

Adjusting for Comparability

When comparing companies using different methods, investors should normalize financial statements using the LIFO reserve.

To convert LIFO to FIFO equivalents:

- Add LIFO reserve to inventory on the balance sheet

- Add LIFO reserve to retained earnings in shareholders’ equity

- Subtract the change in LIFO reserve from COGS on the income statement

- Add the change in LIFO reserve to net income (after tax adjustment)

This conversion allows apples-to-apples comparison of companies in the same industry using different methods.

Evaluating Quality of Earnings

FIFO companies during inflation may show earnings growth that’s partially artificial—a function of accounting rather than operational improvement.

Red flags to watch:

- Margin expansion during inflation: If gross margins improve while input costs rise, FIFO may be inflating profits

- Inventory growth exceeding sales growth: Accumulating inventory inflates assets without corresponding revenue

- Declining inventory turnover: Slower turnover suggests older costs are being held longer

LIFO companies face different quality concerns:

- LIFO liquidations: One-time profit boosts from selling old inventory layers

- Understated assets: Balance sheet inventory may be worth far more than reported

- Hidden reserves: Large LIFO reserves represent deferred tax liabilities that could trigger if inventory is liquidated

Understanding these dynamics helps investors assess whether earnings growth is sustainable or accounting-driven.

Valuation Implications

Inventory methods affect common valuation metrics:

Price-to-Earnings (P/E): FIFO companies show higher earnings during inflation, potentially appearing cheaper on a P/E basis despite identical operations.

Price-to-Book (P/B): LIFO companies show lower book values due to understated inventory, potentially appearing more expensive on a P/B basis.

Enterprise Value to EBITDA (EV/EBITDA): Less affected since EBITDA excludes COGS, but inventory on the balance sheet still impacts enterprise value calculations.

Sophisticated investors adjust for these differences before making valuation comparisons. The economic profit generated by a business is independent of accounting method, but reported metrics vary significantly.

Cash Flow Analysis

The cash flow statement reveals the true economic impact of inventory methods.

During inflation:

FIFO companies show:

- Higher net income (starting point for cash flow)

- Larger increase in inventory (use of cash)

- Higher taxes paid (use of cash)

LIFO companies show:

- Lower net income

- Smaller increase in inventory

- Lower taxes paid (source of cash)

Operating cash flow often converges between methods because the cash effects of inventory changes and tax payments offset the earnings differences.

Free cash flow becomes the ultimate arbiter; it shows cash generated regardless of accounting choices. Investors focused on free cash flow naturally adjust for inventory method differences.

Strategic Considerations for Business Managers

Business leaders choosing between FIFO vs LIFO must weigh multiple factors beyond simple tax minimization.

When to Choose FIFO

Product characteristics favor FIFO when:

- Inventory is perishable or time-sensitive

- Obsolescence risk is high

- Physical flow naturally follows oldest-first

- Products have expiration dates or regulatory requirements

Strategic reasons to choose FIFO:

- International operations require IFRS compliance

- Lenders require higher asset values for collateral

- Management compensation tied to reported earnings

- Company seeks to maximize reported profitability for sale or IPO

- Deflation is expected (FIFO would reduce taxes)

Stakeholder considerations:

- Shareholders prefer higher reported earnings

- Analysts value balance sheet transparency

- Creditors appreciate current asset valuations

When to Choose LIFO

Product characteristics favor LIFO when:

- Inventory is non-perishable and fungible

- Products have long shelf lives

- Obsolescence risk is minimal

- Commodity-like goods with price volatility

Strategic reasons to choose LIFO:

- Tax minimization is the top priority

- Cash flow preservation matters more than reported earnings

- Inflation is expected to continue

- Inventory levels are stable or growing

- Operations are U.S.-only with no IFRS requirements

Financial considerations:

- Lower taxes improve return on invested capital

- Tax savings can fund growth or shareholder distributions

- Conservative earnings reduce overvaluation risk

The Weighted Average Middle Ground

Some companies choose Weighted Average Cost to balance FIFO and LIFO tradeoffs:

Benefits:

- Simpler than LIFO layer tracking

- Smooths profit volatility from price fluctuations

- Provides a moderate tax position between FIFO and LIFO

- Acceptable under both GAAP and IFRS

- Reduces inventory management complexity

Drawbacks:

- Doesn’t optimize for either tax minimization or profit maximization

- Still distorts the balance sheet and income statement during inflation

- Provides less transparency than FIFO

The choice should align with business strategy, industry norms, and stakeholder priorities. Companies should document the rationale and apply the method consistently.

Understanding capital allocation strategies helps managers evaluate how inventory method choices affect overall financial strategy.

Common Misconceptions About FIFO vs LIFO

Several myths about inventory accounting methods persist among investors and business managers.

Myth 1: “FIFO and LIFO Describe Physical Inventory Flow”

Reality: These are cost flow assumptions, not descriptions of physical movement.

A hardware store using LIFO doesn’t actually sell the newest hammers first. The accounting system assumes newer costs flow to COGS, while physical inventory moves; however is practical.

The method chosen can be completely independent of actual physical flow. A grocery store might physically rotate stock (oldest first) while using LIFO for accounting purposes.

Myth 2: “LIFO Is Always Better for Taxes”

Reality: LIFO only provides tax benefits during inflation.

During deflation or stable prices, LIFO can increase taxes. If purchase prices decline, LIFO matches higher old costs against revenue, reducing COGS and increasing taxable income.

Additionally, LIFO liquidations can trigger unexpected tax bills by matching very old, low costs against current revenue.

Myth 3: “Switching Methods Is Easy”

Reality: Changing inventory methods requires disclosure, justification, and often retrospective application.

The IRS scrutinizes method changes to prevent tax manipulation. Companies must demonstrate a valid business reason beyond tax avoidance.

Switching from LIFO to FIFO triggers immediate taxation on the entire LIFO reserve—potentially a massive tax bill representing decades of deferred taxes.

Myth 4: “FIFO Always Shows Higher Profits”

Reality: FIFO shows higher profits only during inflation.

During deflation, FIFO matches old, expensive costs against current revenue, reducing profits below LIFO levels.

The relationship reverses based on price trends. The method that shows higher profits depends entirely on whether costs are rising or falling.

Myth 5: “The Method Doesn’t Matter for Cash Flow”

Reality: Tax differences create real cash impacts.

While operating cash flow eventually converges, the timing of tax payments affects cash available for investment, debt reduction, or distributions.

Tax deferral through LIFO creates a permanent interest-free loan from the government as long as inventory levels are maintained. This cash advantage compounds over time.

Myth 6: “All Companies in an Industry Use the Same Method”

Reality: Method choice varies even within industries.

While industry norms exist, competitive companies often use different methods based on tax strategy, international operations, or management philosophy.

Investors must check each company’s accounting policies rather than assuming uniformity.

The Future of Inventory Accounting

The landscape of inventory accounting continues to evolve with changing regulations, technology, and business models.

Potential LIFO Elimination in the U.S.

Periodic proposals suggest eliminating LIFO under U.S. GAAP to align with IFRS. This would:

- Generate tax revenue: Companies would pay taxes on LIFO reserves, creating a one-time windfall for the government

- Improve comparability: All companies would use FIFO or weighted average, simplifying analysis

- Reduce complexity: Eliminate LIFO layer tracking and conformity rules

- Create transition challenges: Companies would face large tax bills and need to adjust systems

As of 2025, LIFO remains permitted under GAAP, but the possibility of elimination creates uncertainty for companies with large LIFO reserves.

Technology and Real-Time Costing

Advanced inventory management systems enable more sophisticated costing approaches:

Specific identification becomes feasible for more product types as RFID tags, barcodes, and tracking systems improve.

Real-time costing allows companies to match actual costs to specific sales, reducing reliance on assumptions.

Predictive analytics help companies anticipate cost changes and optimize inventory levels.

These technologies may reduce the significance of FIFO vs LIFO choices by enabling more precise cost tracking.

Inflation Trends and Method Selection

The 2021-2024 inflation surge renewed interest in LIFO’s tax benefits. Companies reconsidered method choices as input costs rose sharply.

Future inflation trends will continue influencing method selection:

- Persistent inflation: Increases LIFO adoption for tax benefits

- Return to low inflation: Reduces LIFO advantages

- Deflation: Could make LIFO disadvantageous

Economic conditions shape the financial impact of inventory methods, making the choice increasingly strategic.

ESG and Inventory Accounting

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations may influence inventory accounting:

Waste reduction: FIFO encourages selling older inventory first, potentially reducing spoilage and waste.

Transparency: FIFO provides clearer balance sheet values, improving financial transparency.

Tax fairness: Debates about whether LIFO constitutes appropriate tax planning or avoidance may affect its social license.

As ESG factors gain prominence, inventory method choices may face new scrutiny beyond purely financial considerations.

Practical Steps for Investors Analyzing Inventory Methods

Investors can take concrete actions to account for FIFO vs LIFO differences in their analysis.

Step 1: Identify the Method Used

Check the accounting policies note in the financial statements (usually Note 1 or 2). Companies must disclose their inventory valuation method.

Look for language like:

- “Inventories are valued using the first-in, first-out (FIFO) method.”

- “The Company uses the last-in, first-out (LIFO) method for substantially all inventories.”

- “Inventories are stated at the lower of cost or market using the weighted average cost method.”

Step 2: Find the LIFO Reserve

For LIFO companies, locate the LIFO reserve disclosure in the inventory note. This shows the difference between LIFO and FIFO inventory values.

Example disclosure:

“If the FIFO method had been used, inventories would have been $450 million higher than reported at December 31, 2025.”

Step 3: Adjust Financial Statements

Convert LIFO to FIFO for comparison:

Balance Sheet:

- Add LIFO reserve to inventory

- Add LIFO reserve to retained earnings (net of tax)

Income Statement:

- Subtract the change in LIFO reserve from COGS

- Add change in LIFO reserve to net income (net of tax)

Tax adjustment: Multiply reserve change by the company’s tax rate

Step 4: Recalculate Key Ratios

After adjustments, recalculate metrics:

- Gross margin: (Revenue – Adjusted COGS) ÷ Revenue

- Inventory turnover: Adjusted COGS ÷ Adjusted Inventory

- Current ratio: Adjusted Current Assets ÷ Current Liabilities

- ROA: Adjusted Net Income ÷ Adjusted Total Assets

Step 5: Compare Across Companies

With normalized financials, compare companies using different methods on equal footing.

This reveals true operational differences rather than accounting artifacts.

Step 6: Watch for LIFO Liquidations

Check the financial statement notes for disclosures about LIFO liquidations. These create temporary earnings boosts that should be excluded from normalized earnings.

Example disclosure:

“LIFO liquidations increased net income by $15 million in 2025 compared to $2 million in 2024.”

Adjust earnings downward by the liquidation amount to assess sustainable profitability.

Step 7: Evaluate Management’s Method Choice

Consider why management chose their method:

- Does it align with industry norms?

- Has the method changed recently? Why?

- Does the choice optimize for taxes, reported earnings, or operational alignment?

Method selection reveals management priorities and financial sophistication.

These analytical steps transform FIFO vs LIFO from an accounting technicality into actionable investment intelligence.

Interactive Comparison Tool

📊 FIFO vs LIFO Calculator

Compare how inventory accounting methods affect your financial results

Inventory Purchases

Sales Information

Real-World Case Studies: FIFO vs LIFO in Action

Examining how actual companies use inventory methods reveals practical implications beyond textbook examples.

Case Study 1: ExxonMobil (LIFO User)

ExxonMobil, one of the world’s largest oil companies, uses LIFO for the majority of its inventory. As of their 2024 annual report, the company disclosed a LIFO reserve exceeding $20 billion.

Why LIFO makes sense:

- Crude oil and petroleum products are fungible commodities

- No obsolescence or spoilage risk

- Significant price volatility creates large tax benefits

- U.S.-based operations allow LIFO use

Financial impact:

- The $20+ billion LIFO reserve represents deferred taxes of approximately $5 billion (at a 25% tax rate)

- This deferred tax liability functions as an interest-free loan from the government

- If converted to FIFO, the reported inventory would increase by $20 billion, significantly altering the balance sheet

Investor implications:

- Reported earnings are more conservative than FIFO would show

- True asset value exceeds balance sheet amounts

- Tax efficiency enhances cash flow for dividends and capital investment

Case Study 2: Walmart (LIFO User Transitioning)

Walmart historically used LIFO for U.S. inventory but has gradually shifted toward FIFO as international operations expanded.

The transition challenge:

- International subsidiaries must use FIFO under IFRS

- Maintaining two systems creates complexity

- Comparability across regions becomes difficult

Strategic decision:

- As international sales grew, the benefits of consistent global accounting outweighed LIFO tax advantages

- The company began reducing LIFO inventory and accepting the tax consequences

- This improved financial statement transparency and comparability

Lessons for investors:

- Method changes signal strategic shifts in business operations

- Global expansion often necessitates accounting standardization

- Transition costs (taxes on LIFO reserves) can be substantial

Case Study 3: Kroger (LIFO User)

Kroger, a major grocery chain, uses LIFO for most inventory despite selling perishable goods that physically follow FIFO.

The apparent contradiction:

- Physically, the oldest products sell first to prevent spoilage

- Accounting-wise, LIFO provides tax benefits

- The cost flow assumption is independent of physical flow

Financial impact:

- Kroger’s LIFO reserve was approximately $1.5 billion in recent years

- Tax savings fund competitive pricing and store improvements

- Reported margins are more conservative than FIFO competitors

Competitive analysis:

- Comparing Kroger (LIFO) to other grocers (FIFO) requires adjustments

- Kroger’s tax efficiency may provide a competitive advantage in a low-margin industry

- Investors must normalize financials to assess true operational performance

Case Study 4: Apple (FIFO User)

Apple uses FIFO for all inventory, consistent with technology industry norms.

Why FIFO makes sense:

- Technology products face rapid obsolescence

- Inventory turns quickly (typically 5-10 days)

- International operations require IFRS compliance

- The inventory method has minimal impact, given the fast turnover

Financial characteristics:

- High inventory turnover minimizes the difference between FIFO and LIFO

- Balance sheet inventory represents very recent purchases

- Method choice has a negligible tax impact given short holding periods

Industry pattern:

- Most technology companies use FIFO

- Fast inventory turnover reduces the significance of method choice

- Product lifecycle management matters more than accounting methods

These case studies demonstrate that industry characteristics, business strategy, and operational realities drive inventory method selection. The optimal choice varies by company and context.

Conclusion: Making Sense of FIFO vs LIFO for Better Investment Decisions

The choice between FIFO vs LIFO represents far more than an accounting technicality. It’s a strategic decision that shapes reported profits, tax obligations, balance sheet values, and ultimately, how investors perceive company performance.

FIFO provides balance sheet transparency by keeping inventory values current, making it ideal for perishable goods, international operations, and companies prioritizing reported earnings over tax minimization. During inflation, FIFO shows higher profits but creates larger tax bills.

LIFO offers tax efficiency by matching recent costs against revenue, making it valuable for non-perishable commodities during inflationary periods. It produces more conservative earnings and better income statement matching, but distorts balance sheet values and adds complexity.

Neither method is universally superior. The optimal choice depends on:

- Product characteristics: Perishable versus non-perishable

- Price trends: Inflation versus deflation

- Geographic scope: Domestic versus international

- Strategic priorities: Tax minimization versus earnings maximization

- Industry norms: Competitive comparability

For investors, understanding FIFO vs LIFO transforms financial statement analysis from surface-level number-crunching to a deep comprehension of economic reality. The same business can report vastly different metrics depending solely on accounting method choice.

Actionable steps for investors:

- Check inventory accounting policies in every company you analyze

- Adjust for LIFO reserves to enable fair comparisons

- Watch for LIFO liquidations that distort earnings

- Consider the industry context when evaluating method choices

- Focus on cash flow as the ultimate arbiter of economic performance

- Understand tax implications and their impact on shareholder returns

The math behind money includes understanding how accounting choices affect the numbers that drive investment decisions. FIFO vs LIFO isn’t just accounting—it’s a lens for seeing through reported financials to the economic truth beneath.

Companies that master inventory accounting optimize tax strategy while maintaining financial transparency. Investors who understand these methods gain a competitive advantage through superior analysis and valuation accuracy.

The difference between FIFO and LIFO can mean millions in taxes, billions in reported asset values, and percentage points in profit margins. In the data-driven world of investing fundamentals, that difference matters.

For a deeper understanding of how accounting choices affect investment analysis, explore related topics like accounting profit, economic profit, and financial statement relationships.

The journey to financial literacy includes mastering the technical details that separate sophisticated investors from casual observers. FIFO vs LIFO represents one crucial piece of that puzzle, a piece that transforms how you read financial statements and evaluate business quality.

Start applying these principles today. Review the inventory accounting policies of companies in your portfolio. Calculate the LIFO reserve impact on reported earnings. Compare competitors using normalized financials. These practical steps convert knowledge into actionable investment intelligence.

The math behind inventory accounting is clear. The choice between FIFO and LIFO creates measurable, predictable financial effects. Understanding these effects empowers better investment decisions based on evidence, logic, and economic truth.

Sources

[1] Corporate Finance Institute – FIFO vs LIFO Inventory Valuation Methods

[2] Investopedia – Understanding FIFO and LIFO Accounting

[3] Financial Accounting Standards Board – Inventory Accounting Standards

[4] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission – Financial Reporting Guidelines

[5] Journal of Accountancy – Tax Implications of Inventory Methods

Author Bio

Max Fonji is the founder of The Rich Guy Math, a data-driven financial education platform dedicated to teaching the math behind money. With expertise in financial analysis, valuation principles, and evidence-based investing, Max breaks down complex financial concepts into clear, actionable insights. His work focuses on helping investors understand the quantitative foundations of wealth building, risk management, and financial decision-making through logic, data, and proven frameworks.

Educational Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. The content represents general information about inventory accounting methods and should not be relied upon as the sole basis for financial decisions.

Inventory accounting methods have complex tax implications that vary based on individual circumstances, jurisdiction, and regulatory changes. Consult with qualified accounting, tax, and financial professionals before making decisions about inventory valuation methods or investment strategies.

While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, financial regulations and accounting standards change over time. Verify current rules with authoritative sources before applying concepts discussed in this article.

Past performance and historical examples do not guarantee future results. Investment decisions should be based on comprehensive analysis, personal financial circumstances, and professional guidance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main difference between FIFO and LIFO?

FIFO (First-In, First-Out) assumes the oldest inventory is sold first, matching old costs against current revenue. LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) assumes the newest inventory is sold first, matching recent costs against current revenue. During inflation, FIFO shows higher profits and higher taxes, while LIFO shows lower profits and lower taxes.

Which inventory method is better for taxes?

LIFO typically provides better tax outcomes during inflation because it matches higher recent costs against revenue, reducing taxable income. However, LIFO only benefits companies during periods of rising prices. During deflation or stable prices, FIFO may be more advantageous. The optimal method depends on price trends and business circumstances.

Can companies use FIFO for taxes and LIFO for financial reporting?

No. The LIFO conformity rule requires companies using LIFO for tax purposes to also use it for financial reporting. This prevents companies from presenting different results to the IRS and investors. FIFO can be used for both, but methods cannot be split.

Why is LIFO not allowed under IFRS?

IFRS prohibits LIFO because it does not reflect actual physical inventory flows and can distort the financial position of a company. Since most inventory does not move in a last-in-first-out pattern, IFRS considers LIFO inconsistent with representational faithfulness and global comparability.

How do I compare companies using different inventory methods?

Use the LIFO reserve to adjust the financial statements. Add the LIFO reserve to inventory and retained earnings to approximate FIFO values. Subtract the change in the LIFO reserve from COGS to estimate FIFO COGS. This adjustment enables apples-to-apples comparison across companies.

What happens if a LIFO company liquidates inventory?

LIFO liquidation occurs when a company sells more inventory than it purchases, dipping into older LIFO layers. This matches low historical costs against current revenue, temporarily inflating profits and tax liabilities. Companies must disclose LIFO liquidations, and analysts should adjust earnings to remove these non-recurring gains.

Which industries typically use LIFO?

Industries with non-perishable, fungible goods and inflation exposure often use LIFO. Common examples include oil and gas, steel and metals, automotive manufacturing, building materials, and wholesale distribution. These sectors benefit from tax deferral under inflationary conditions.

Does inventory method affect cash flow?

Yes. While long-run operating cash flow converges, tax timing creates meaningful cash flow differences. LIFO lowers taxes during inflation, preserving cash for reinvestment. FIFO increases taxable income, reducing cash on hand. The cash flow statement reflects these impacts through tax payments and inventory changes.